© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Paediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome

and haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis

complications of scrub typhus: a case report

Ronald CM Fung, MB, ChB, MRCPCH1; Karen KY Leung, MB, BS, MRCPCH1; CC Au, MB, BS, MRCPCH2; KN Cheong, MB, BS, MRCPCH2; Mike YW Kwan, MRCPCH3; Grace KS Lam, MB, BS, MRCPCH2; KL Hon, MB, BS, MD1

1 Paediatric Intensive Care Unit, Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, The Hong Kong Children’s Hospital, Hong Kong

2 Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, The Hong Kong Children’s Hospital, Hong Kong

3 Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Prince Margaret Hospital, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr KL Hon (ehon@hotmail.com)

In June 2020, a previously healthy 7-year-old boy

presented with a 1-week history of persistent fever.

He had an unremarkable medical history, and had

gone hiking a week before the onset of his fever.

He was initially treated for a presumed viral illness

but his condition worsened over the subsequent

2 days. His fever became high and fluctuating, with

a peak of 39°C, and he developed dyspnoea without

cough. He had no headache or body aches. Physical

examination revealed crepitations with diminished

breath sounds over both lung fields and tachypnoea

with a respiratory rate of 30 per minute. Cervical

lymphadenopathy and hepatomegaly were present.

There was no eschar. He had distributive shock

with hypotension (80/40 mm Hg) and tachycardia

(150 beats per minute) and a norepinephrine

infusion was commenced. Within one day, type I respiratory failure became evident with increasing

oxygen requirement from room air to FiO2 0.4 and

continuous positive airway pressure of 6 cmH2O

to maintain oxygen saturation above 90%. The

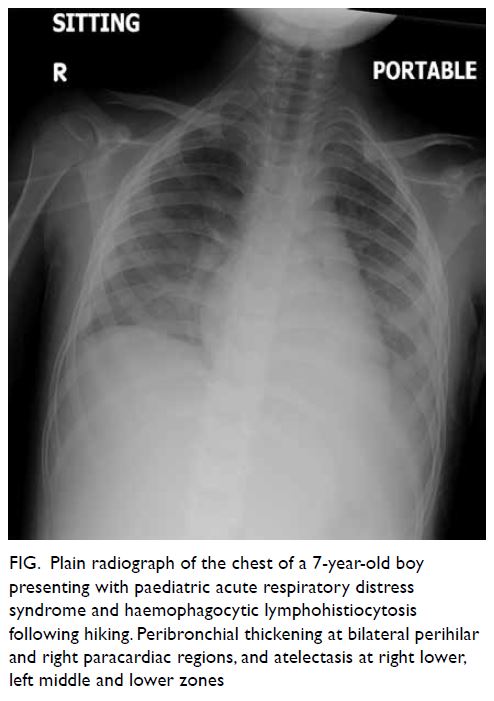

PaO2:FiO2 ratio was 232.5 mm Hg. Plain radiograph

of the chest revealed bilateral opacities and

peribronchial thickening (Fig). Echocardiography

and lung ultrasound confirmed normal heart

function and the absence of pleural effusion. By

definition, the boy was diagnosed with paediatric

acute respiratory distress syndrome (PARDS: an

acute lung injury occurring within 7 days of a

known clinical insult, with acute hypoxaemia of

PaO2:FiO2 ratio ≤300 when the child is on non-invasive

ventilation, and new infiltrates consistent

with acute pulmonary parenchymal disease on

chest radiograph, which cannot be explained by acute left ventricular heart failure or fluid overload),

where he had progressive respiratory failure and

bilateral diffuse infiltration on chest radiography.1

Further blood tests and bone marrow findings

met the diagnostic criteria for haemophagocytic

lymphohistiocytosis (HLH: a life-threatening

clinical syndrome of systemic hyperinflammation

and progressive immune-mediated organ damage due to excessive immune activation): anaemia

(haemoglobin 8.3 g/dL), thrombocytopenia

(45 × 109/L), hypertriglyceridaemia (4.5 mmol/L),

high ferritin (4467 pmol/L), hypofibrinogenaemia

(0.9 g/L), and elevated soluble CD25 (8569 pg/mL).2

Bone marrow aspiration and trephine biopsy

showed haemophagocytosis. There was no

evidence of Epstein–Barr virus association

on immunohistochemical analysis. Orientia

tsutsugamushi antibody titre of 512 increased to

4096 (ie, more than a fourfold increase) after 2 weeks.

The child was diagnosed with PARDS and secondary

HLH associated with scrub typhus infection and prescribed oral doxycycline 50 mg twice daily

(~3.7 mg/kg/day) for the scrub typhus. Intravenous

dexamethasone 5 g every 12 hours (10 mg/m2/day)

was commenced as treatment of HLH with a starting

dose as per the HLH-2004 study protocol. He became

afebrile within 1 day of commencing treatment

and respiratory distress gradually resolved. He was

weaned off continuous positive airway pressure

ventilation after 3 days. Platelet count rose to

>100 × 109/L after 4 days. Ferritin lowered the day

after treatment and was within normal range after

2 weeks. The boy completed a 1-week course of

doxycycline and dexamethasone was also tapered off

in 1 week.

Figure. Plain radiograph of the chest of a 7-year-old boy presenting with paediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome and haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis following hiking. Peribronchial thickening at bilateral perihilar and right paracardiac regions, and atelectasis at right lower, left middle and lower zones

Discussion

Our patient presented with non-specific

symptoms of scrub typhus and developed severe

complications including PARDS and HLH without

the pathognomonic eschar. Scrub typhus is caused

by the bacterium O tsutsugamushi and is spread

to humans through the bites of infected chiggers,

Leptotrombidium mites, that can be both a vector

and a reservoir for O tsutsugamushi.3 It is a notifiable

disease in Hong Kong with between 7 and 28 cases

reported each year over the past 10 years.4 Symptoms

of scrub typhus usually begin within 10 days of

being bitten and can range from non-specific signs

including fever, headache, body aches and rash, to

multiorgan failure and death with a median mortality

rate of 6% if left untreated.3 Although eschar is

pathognomonic for scrub typhus, it is rare among

Southeast Asian patients. Laboratory confirmation

of the diagnosis usually requires indirect fluorescent

antibody test and is the mainstay of serologic

diagnosis. Polymerase chain reaction assay of whole

blood sample if available can speed the diagnosis.

Acute respiratory distress syndrome is a serious

complication of scrub typhus; it has been reported in

4% to 22% of cases,5 6 and can involve over 50% of

children who developed secondary HLH associated

with scrub typhus infection.7 The pulmonary

manifestations vary from bronchitis and interstitial

pneumonitis to acute respiratory distress.5 6 Acute

respiratory distress has also manifested in many

patients with HLH due to other causes and has been

reported as the initial manifestation of HLH. Nahum

et al8 reported that 7 of 11 children with HLH and

multiple organ failure exhibited PARDS after HLH

was diagnosed, highlighting the importance of close

monitoring and early intervention for children

with PARDS and HLH. The presentation of acute

respiratory distress syndrome in children differs from

that in adults and a consensus on a formal PARDS

definition was reached in 2015 by the Paediatric

Acute Lung Injury Consensus Conference.1

In some cases, HLH can cause cytokine release syndrome, a life-threatening disorder of

severe excessive inflammation (hyperinflammation)

caused by uncontrolled proliferation of activated

lymphocytes, macrophages and secretion of

inflammatory cytokines.9 Although rare, O

tsutsugamushi is a significant cause of HLH,

especially in Asia.7 The HLH-2004 protocol,

which includes etoposide, dexamethasone and

cyclosporine as the initial therapy, is designed

for treatment of patients with primary HLH.2 For

patients with secondary HLH, treatment of the

underlying infection or malignancy may help control

the HLH and avoid the need for cyclosporine and

etoposide. Single antibiotic therapy with doxycycline,

minocycline, chloramphenicol, azithromycin or

clarithromycin has been reported to result in rapid

defervescence in patients with HLH associated

with scrub typhus.10 Thus, an accurate diagnosis of

scrub typhus in patients with HLH can help timely

targeted antibiotic therapy with subsequent rapid

clinical improvement.

This case illustrates an atypical severe

manifestation of scrub typhus presenting with

non-specific signs and symptoms resulting in

complications including PARDS and HLH. Early

diagnosis and treatment with doxycycline are crucial

to prevent complications. Physicians should be

vigilant for scrub typhus as a potential diagnosis

in a child who presents with pyrexia of unknown

origin and a history of participation in rural outdoor

activities.

Author contributions

Concept or design: RCM Fung, KKY Leung, CC Au, KL Hon.

Acquisition of data: RCM Fung, KL Hon.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: RCM Fung, KKY Leung, KL Hon.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: RCM Fung, KL Hon.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: RCM Fung, KKY Leung, KL Hon.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

As an editor of the journal, KL Hon was not involved in the peer review process. Other authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The patient was treated in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. The patient’s parents provided

written informed consent for all treatments and procedures

and consent for publication.

References

1. Pediatric Acute Lung Injury Consensus Conference

Group. Pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome:

consensus recommendations from the Pediatric Acute

Lung Injury Consensus Conference. Pediatr Crit Care Med

2015;16:428-39. Crossref

2. Henter JI, Horne A, Aricó M, et al. HLH-2004: Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic

lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2007;48:124-31. Crossref

3. Peesapati N, Rohit T, Sunitha S, Pv S. Clinical manifestations and complications of scrub typhus: a hospital-based study from North Andhra. J Assoc Physicians India 2019;67:22-4.

4. Center for Health Protection, Department of Health, Hong

Kong SAR Government. Number of notifiable infectious

diseases by month. 2020. Available from: https://www.chp.gov.hk/en/statistics/data/10/26/43/6896.html. Accessed 25 Jun 2020.

5. Sankuratri S, Kalagara P, Samala KB, Veledandi PK, Crossref

6. Kumar Bhat N, Dhar M, Mittal G, et al. Scrub typhus in children at a tertiary hospital in north India: clinical profile and complications. Iran J Pediatr 2014;24:387-92.

7. Naoi T, Morita M, Kawakami T, Fujimoto S. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis associated with

scrub typhus: Systematic review and comparison between

pediatric and adult cases. Trop Med Infect Dis 2018;3:19. Crossref

8. Nahum E, Ben-Ari J, Stain J, Schonfeld T. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytic syndrome: Unrecognized cause of

multiple organ failure. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2000;1:51-4. Crossref

9. Hon KL, Leung KK, Oberender F, Leung AK. Paediatrics: how to manage septic shock. Drugs Context 2021;10:2021-1-5. Crossref

10. Hon KL, Leung AS, Cheung KL, et al. Typical or atypical

pneumonia and severe acute respiratory symptoms in

PICU. Clin Respir J 2015;9:366-71. Crossref