Hong Kong Med J 2021 Dec;27(6):461–3 | Epub 17 Dec 2021

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

COMMENTARY

Critically ill children in paediatric intensive care unit are no less susceptible to infectious diseases amid the COVID-19 pandemic

Karen KY Leung, MB, BS, MRCPCH1; KL Hon, MB, BS, MD1; Patrick Ip, MB, BS, MD2; Renee WY Chan, PhD3,4,5,6

1 Paediatric Intensive Care Unit, Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, The Hong Kong Children’s Hospital, Hong Kong

2 Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

3 Department of Paediatrics, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

4 Hong Kong Hub of Paediatric Excellence, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

5 Laboratory for Paediatric Respiratory Research, Li Ka Shing Institute of Health Sciences, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

6 CUHK-UMCU Joint Research Laboratory of Respiratory Virus & Immunobiology, Department of Paediatrics, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr KL Hon (ehon@hotmail.com)

With the lifting of various measures intended to limit

the spread of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19),

paediatric cases have been on the rise, with

approximately 2% to 6% of those infected becoming

critically ill.1 2 3 4 5 6 During the early phase of the

pandemic, a review of 2135 paediatric cases in China

revealed the proportion of severe and critical illness

to be higher in the younger age-group, in particular

infants.5 In a separate report by the United States

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 62%

of those aged <1 year were hospitalised compared

with 4.1% to 14% among those aged 1 to 17 years.6

However as the pandemic evolves, the epidemiology

seems to have changed and COVID-19 is now

affecting older children more severely. In the latest

report from the United States, critically ill children

with COVID-19 were predominantly adolescents,

had co-morbidities, and required some form of

respiratory support.7 In many cases, the presence of

acute respiratory distress syndrome was associated

with prolonged paediatric intensive care (PICU) and

hospital stay.8

Recently there has been an emergence of

paediatric hyperinflammatory and shock syndromes

including paediatric inflammatory multisystem

syndrome (PIMS), MIS-C (multisystem inflammatory

syndrome in children), and PIMS-TS (paediatric

inflammatory multisystem syndrome temporally

associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome

coronavirus 2 [SARS-CoV-2]).9 10 These are systemic

diseases involving persistent fever, inflammation and

organ dysfunction associated with SARS-CoV-2;

80% of the patients with this new disease entity

require intensive care support with a 2% fatality

rate.3 11 12 13 Furthermore, COVID-19 is associated with

dysfunction across many organ systems as in PIMS as

well as syndromes such as COVID stress syndrome

and COVID toe syndrome.14

Unlike other respiratory viruses such as

influenza and respiratory syncytial virus, there

has fortunately been no paediatric mortality due

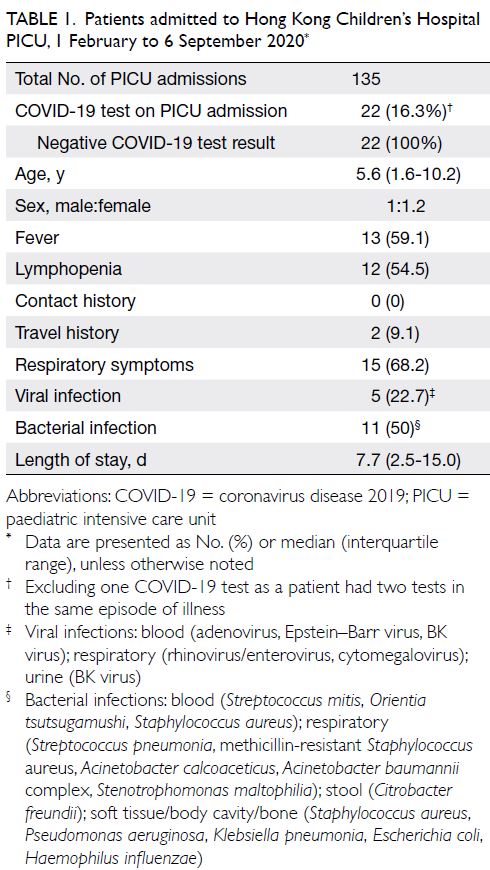

to COVID-19 in Hong Kong. We reviewed all

admissions to the Hong Kong Children’s Hospital

PICU with nasal pharyngeal swab/aspiration for

SARS-CoV-2 between 1 February and 6 September

2020, and found that 22 (16.3%) of our admitted

patients were tested and they were all negative for

COVID-19 (Table 1). During the early stages of

the COVID-19 epidemic in Hong Kong, screening

for COVID-19 was not universal for all PICU

admissions; only patients meeting set criteria were

screened, primarily in-patients, patients acutely

admitted, or patients transferred in who had not

already been tested. Patients who had been tested

negative elsewhere or in-patients with no exposure

were not tested in the initial phase of the pandemic.

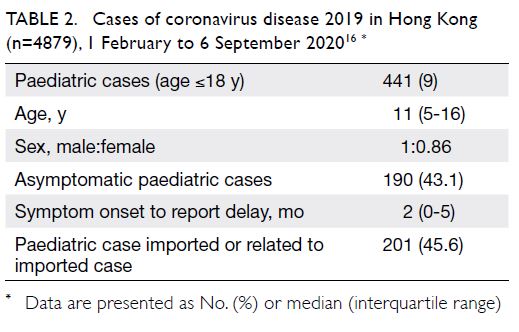

During the same period, there were 441 (9%) of

COVID-19 cases in Hong Kong were aged ≤18 years

(Table 2 15). In addition to SARS-CoV-2, various

viral and bacterial pathogens were isolated in these

paediatric patients with COVID-19. Viruses isolated

include adenovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, and BK

virus in blood samples; rhinovirus, enterovirus, and

cytomegalovirus in respiratory specimens; and BK

virus in urine samples. A wide variety of bacteria were

also isolated, including a case of hyperinflammatory

hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis syndrome due

to Orientia tsutsugamushi instead of SARS-CoV-2.

Compared with paediatric patients with SARS-CoV-2

in the community, viral and bacterial infections were

present in 22.7% and 50% of SARS-CoV-2 negative

patients in our PICU cohort, respectively (P<0.001).

The COVID-19 screening criteria changed as the

pandemic evolved and it is now mandatory to screen

every patient admitted to the PICU for COVID-19.

In our opinion, it is unlikely that PICUs in Hong Kong have missed any cases of COVID-19.

During the pandemic, it is easy to overestimate

the prevalence of COVID-19 due to cognitive bias,

and assume all patients with fever are infected

with COVID-19 until proven otherwise, leading

to potential therapeutic errors.16 However, our

observations have concluded that critically ill children are susceptible to contracting a whole host

of infectious diseases. Therefore, in addition to

screening for COVID-19, physicians must also be

vigilant of other pathogens that could affect critically

ill children, and duly take antimicrobial and isolation

precautions within healthcare environments. It

appears that SARS-CoV-2 infection is generally an

asymptomatic or very mild disease in children. In

contrast, serious viral and bacterial infections are

associated with critically ill children tested negative

for SARS-CoV-2.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the concept or design, acquisition of data, analysis or interpretation of data, drafting of the

manuscript, and critical revision of the manuscript for

important intellectual content. All authors had full access to

the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version

for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and

integrity.

Conflicts of interest

As the editor of the journal, KL Hon was not involved in the peer review process for the article. Other authors have no

conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

1. Hon KL, Leung KK. Paediatrics is a big player of COVID-19 in Hong Kong [Letter]. Hong Kong Med J

2020;26:265-6. Crossref

2. Hon KL, Leung KK. Pediatric COVID-19: what disease is this? World J Pediatr 2020;16:323-5. Crossref

3. Hon KL, Leung KK, Leung AK, et al. Overview: the history

and pediatric perspectives of severe acute respiratory

syndromes: novel or just like SARS. Pediatr Pulmonol

2000;55:1584-91. Crossref

4. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA 2020;323:1239-42. Crossref

5. Dong Y, Mo X, Hu Y, et al. Epidemiology of COVID-19 among children in China. Pediatrics 2020;145:e20200702. Crossref

6. CDC COVID-19 Response Team. Coronavirus Disease 2019 in children—United States, February 12-April 2,

2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:422-6. Crossref

7. Derespina KR, Kaushik S, Plichta A, et al. Clinical manifestations and outcomes of critically ill children and

adolescents with Coronavirus Disease 2019 in New York

City. J Pediatr 2020;226:55-63.e2. Crossref

8. Pathak EB, Salemi JL, Sobers N, Menard J, Hambleton IR.

COVID-19 in children in the United States: intensive

care admissions, estimated total infected, and projected

numbers of severe pediatric cases in 2020. J Public Health

Manag Pract 2020;26:325-33. Crossref

9. Joshi K, Kaplan D, Bakar A, et al. Cardiac dysfunction and shock in pediatric patients with COVID-19. JACC Case Rep 2020;2:1267-70. Crossref

10. Riphagen S, Gomez X, Gonzalez-Martinez C, Wilkinson N, Theocharis P. Hyperinflammatory shock in children during

COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 2020;395:1607-8. Crossref

11. Feldstein LR, Rose EB, Horwitz SM, et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in U.S. Children and Adolescents.

N Engl J Med 2020;383:334-6. Crossref

12. Paediatric Intensive Care Society. PICS Statement:

increased number of reported cases of novel presentation

of multi system inflammatory disease. 2020. Available from:

https://pccsociety.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/PICS-statement-re-novel-KD-C19-presentation-v2-27042020.pdf. Accessed 25 Sep 2020.

13. The Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health. Paediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome temporally associated with COVID-19 (PIMS)—guidance

for clinicians. 2020. Available from: https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/resources/paediatric-multisystem-inflammatory-syndrome-temporally-associated-covid-19-pims-guidance. Accessed 25 Sep 2020.

14. Rose-Sauld S, Dua A. COVID toes and other cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19. J Wound Care 2020;29:486-7. Crossref

15. Centre for Health Protection, Hong Kong SAR

Government. Latest situation of cases of COVID-19 (as

of 24 September 2020). 2020. Available from: https://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/local_situation_covid19_en.pdf. Accessed 24 Sep 2020.

16. Zagury-Orly I, Schwartzstein RM. Covid-19—A reminder to reason. N Engl J Med 2020;383:e12. Crossref