Hong Kong Med J 2021 Dec;27(6):458–60 | Epub 12 Nov 2021

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

COMMENTARY

Celebrating 60 years of corneal transplant in

Hong Kong

KW Kam, FRCS (Glasg), MSc Epidemiology (London)1,2; Victoria WY Wong, FRCSEd, FRCOphth2,3,4; Vanissa WS Chow, FRCSEd, FCOphthHK5; Evan PF Yiu, FRCS (Glasg), FHKAM (Ophthalmology)6; Alvin L Young, MMedSc (Hons), FRCOphth1,2

1 Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong Kong

2 Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

3 HKU Health System, Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

4 Department of Ophthalmology, Queen Mary Hospital and Grantham Hospital, Hong Kong

5 Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, Hong Kong Eye Hospital, Hong Kong

6 Tuen Mun Eye Centre, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Prof Alvin L Young (youngla@ha.org.hk)

Visual restoration through transplantation was

limited to animal experiments until the first

successful human corneal transplant more than a

century ago in the Czech Republic area.1 Nowadays,

corneal transplant/keratoplasty is one of the most

commonly performed transplantation globally.

However, 4.2 million people still have corneal

blindness making it the fourth leading cause

of blindness according to the World Health

Organization, and graft scarcity remains a challenge.2

In Hong Kong, the first corneal transplant was

performed in 1961 at Tung Wah Eastern Hospital.

The expatriate surgeons performed many corneal

transplants using fresh corneas from American

eye banks (Fig a, b). This led to the establishment

of the Hong Kong Eye Bank (HKEB) and Research

Foundation in 1962.3

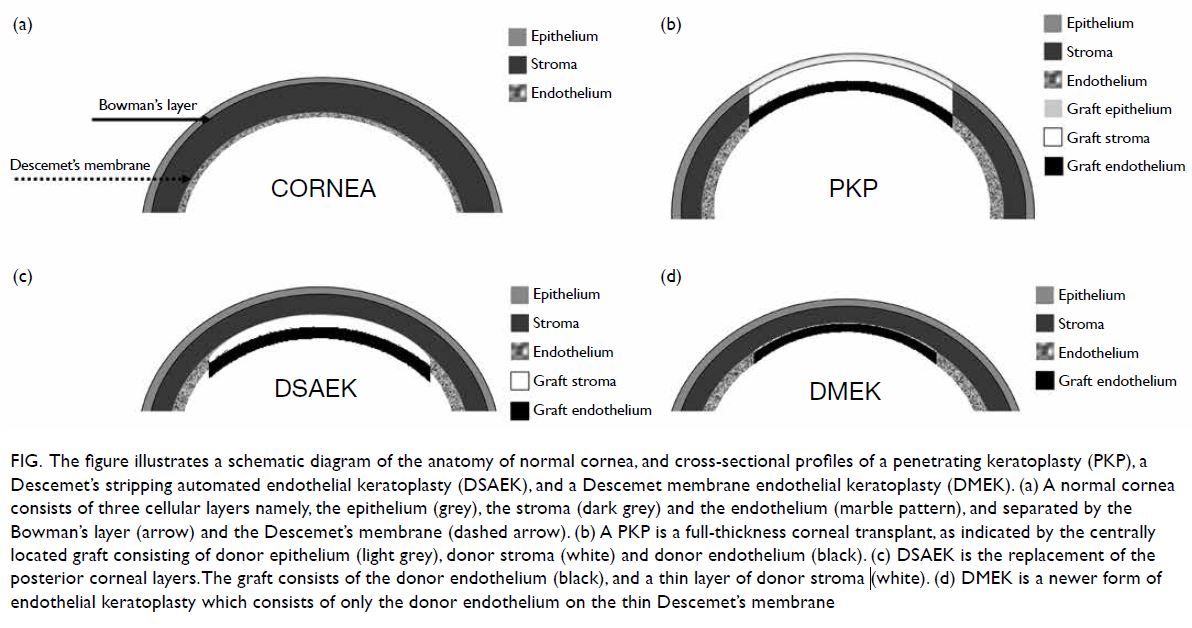

Figure. The figure illustrates a schematic diagram of the anatomy of normal cornea, and cross-sectional profiles of a penetrating keratoplasty (PKP), a Descemet’s stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty (DSAEK), and a Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK). (a) A normal cornea consists of three cellular layers namely, the epithelium (grey), the stroma (dark grey) and the endothelium (marble pattern), and separated by the Bowman’s layer (arrow) and the Descemet’s membrane (dashed arrow). (b) A PKP is a full-thickness corneal transplant, as indicated by the centrally located graft consisting of donor epithelium (light grey), donor stroma (white) and donor endothelium (black). (c) DSAEK is the replacement of the posterior corneal layers. The graft consists of the donor endothelium (black), and a thin layer of donor stroma (white). (d) DMEK is a newer form of endothelial keratoplasty which consists of only the donor endothelium on the thin Descemet’s membrane

In the early years, the HKEB functioned mainly

as a distributing centre, because local donation was

rare. The concept of eye donation after death was

not widely accepted, because local eye surgeons

were sceptical regarding the success rate of corneal

transplant in the era before microscopic surgery,

and many local citizens subscribed to Confucian’s

ideology of ‘filial piety’, that is, a person’s body, hair,

and skin are gifts from their parents that should not

be damaged. As a result, the HKEB had to rely on

imported tissues from the International Eye Bank in

Sri Lanka. During the 1970s to 80s, between 20 and

40 corneas were flown to Hong Kong annually which

was insufficient to meet the local demand.

In the following decade there was a gradual

acceptance of organ donation after death, as solid

organ transplantation became available, society

became more Westernised, and levels of education

and public awareness were increased. Moreover, a

shortage of burial plots led to a shift to cremation,

weakening the concept of preserving a whole body

for the afterlife. In the 90s, even patients with

unilateral corneal blindness were keen to undergo surgery. To address soaring demand and the variable

quality of tissue from Sri Lanka, the HKEB started

harvesting corneas from local donors in 1992. The

quality of locally harvested cornea continued to

improve, and in 1997, importation from Sri Lanka

was stopped.

Since 2000, the Hospital Authority (HA) of

Hong Kong assumed responsibility for managing

organ supply, and the HKEB was renamed the HA

Lions Eye Bank. Management was later transferred

to the Hong Kong Eye Hospital from December 2009

and was again renamed the HA Eye Bank (HAEB)

from July 2016.

The HAEB has made great strides in

governance, quality, safety, personnel training, and

credentialing in meeting international standards.

Strategic partnerships with leading eye banks have

provided opportunities for progress. Since 2015,

HAEB has collaborated with Sight Life on quality

certification and entered into a global partnership

with Sight Life in 2017. This has strengthened

the HAEB in the regional eye banking scene. This

is reflected in the fact that >300 corneal buttons

have been harvested annually since 2017. As of

31 December 2020, 280 patients were on the waiting

list for a corneal transplant. The average waiting time

has now shortened to around 1 year. The youngest

donor was a 20-month-old infant and the oldest

cornea recipient was a centenarian. Unfortunately,

similar to other transplant activities, donation and

harvest rates have been adversely affected by the

coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic.

Graft scarcity remains the limiting factor

for the total number of keratoplasty procedures

performed each year. A global survey revealed

that 12.7 million people were waiting for a corneal

transplant and only one in 70 of those would receive

a cornea.4

Novel surgical techniques emerged to

selectively replace diseased corneal layers in the form of lamellar keratoplasty. With the aid of

ophthalmic microscopes, finer surgical instruments

and equipment, corneal surgeons migrated towards

partial-thickness corneal transplants. In addition to

better visual outcomes and lower risks of rejection, a

single donor cornea may be transplanted into two or

more patients with different pathologies.5

One of the more popular forms of lamellar

keratoplasty is endothelial keratoplasty (Fig c), which

replaces the diseased corneal endothelium and allows

for the restoration of corneal clarity.6 In January 2005,

the first Descemet stripping endothelial keratoplasty

was successfully performed at the Prince of Wales

Hospital. This operation required meticulous

dissection of the donor cornea into a thicker anterior

portion and a very thin posterior layer. The posterior

lenticule (<200 μm) was implanted into the patient’s

eye and secured only by a gas bubble without any

need for suturing. Chinese eyes are known to

be technically challenging; nonetheless, visual

outcomes and complication profiles of procedures

conducted in Hong Kong patients are comparable to

international standards.7 8 9

As endothelial keratoplasty gained popularity,

in 2008, the HKEB also started to pre-cut corneal

tissues for surgeons. Having pre-cut tissues

significantly reduces the operating time and obviates

any risks of cancellation due to inadvertent graft

damage during preparation.

In 2011, Tuen Mun Eye Centre performed the

first Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK).10 This form of endothelial keratoplasty

involves a much thinner donor than Descemet

stripping endothelial keratoplasty, yielding the

potential of less rejection risk and better vision (Fig d). As this membrane is extremely thin and delicate, accidental tears during preparation may occur

leading to wastage. This must be weighed against

graft shortages. Recently, a modified endothelium-in

technique utilising a pull-through device was

developed in Singapore.11 This technique was first

applied at the Caritas Medical Centre in late 2020.

In February 2013, the HAEB updated the local

criteria for cornea donation in accordance with

American and European standards.12 The pool of

potential donors was thus expanded as patients with

solid organ malignancy were able to donate their

corneas after death. In August 2018, The Chinese

University of Hong Kong Jockey Club Ophthalmic

Microsurgical Training Programme started the

first penetrating keratoplasty simulated training for

young ophthalmologists. As DMEK gains popularity,

the HAEB will advance to preparation of pre-stripped

DMEK grafts for surgeons. In May 2021, the HAEB

organised the first territory-wide DMEK wet lab for

corneal surgeons to gain hands-on experience with

stripped endothelial grafts. This was followed by a

wet lab organised by the Caritas Medical Centre on

their experience of endothelium-in DMEK.

Common to solid organ grafting, there is a

limited lifespan for any transplanted corneal graft.

In cases where further grafts are not indicated, one could resort to artificial corneas. Apart from the

more established osteo-odonto-keratoprosthesis13

and Boston keratoprosthesis, newer forms of

artificial corneas are being developed.

Corneal surgeons are excited about the

potential rho-kinase inhibitors medical therapy,

which could restore corneal endothelial health. The

use of cultivated human corneal endothelial cells and

injecting such into the anterior chamber will likely

revolutionise the concept of corneal transplant.14

As we gain knowledge in corneal genetics, we

may even be able to prevent corneal degeneration

from the outset with genetic therapy.15

Author contributions

Concept or design: AL Young.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: KW Kam.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: AL Young.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: KW Kam.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: AL Young.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge the tremendous support and contributions from Ms Catherine Wong,

Manager of the Hong Kong Eye Bank.

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval is not required for this commentary which did not involve human or animal subjects.

References

1. Crawford AZ, Patel DV, McGhee CN. A brief history of corneal transplantation: from ancient to modern. Oman J

Ophthalmol 2013;6(Suppl 1):S12-7. Crossref

2. Wong KH, Kam KW, Chen LJ, Young AL. Corneal blindness

and current major treatment concern-graft scarcity. Int J

Ophthalmol 2017;10:1154-62.

3. Ho PC. Thirty-five years of eye banking in Hong Kong—a

metamorphosis and a commitment renewed. Hong Kong J

Ophthalmol 1997;1:19-24.

4. Gain P, Jullienne R, He Z, et al. Global survey of corneal

transplantation and eye banking. JAMA Ophthalmol

2016;134:167-73. Crossref

5. Young AL, Kam KW, Jhanji V, Cheng LL, Rao SK. A new era

in corneal transplantation: paradigm shift and evolution of

techniques. Hong Kong Med J 2012;18:509-16.

6. Young AL, Rao SK, Cheng LL, Lam PT. Endothelial keratoplasty. Hong Kong J Ophthalmol 2008;12:25-32.

7. Li AL, Kwok RP, Kam KW, Young AL. A 5-year analysis of endothelial vs penetrating keratoplasty graft survival in Chinese patients. Int J Ophthalmol 2020;13:1374-7. Crossref

8. Young AL, Kwok RP, Jhanji V, Cheng LL, Rao SK. Long-term outcomes of endothelial keratoplasty in Chinese eyes at a University Hospital. Eye Vis (Lond) 2014;1:8. Crossref

9. Young AL, Rao SK, Lam DS. Endothelial keratoplasty: where are we? Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2008;36:707-8. Crossref

10. Monnereau C, Quilendrino R, Dapena I, et al. Multicenter study of descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty: first case series of 18 surgeons. JAMA Ophthalmol

2014;132:1192-8. Crossref

11. Ang M, Mehta JS, Newman SD, Han SB, Chai J, Tan D. Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty: preliminary

results of a donor insertion pull-through technique using a

donor mat device. Am J Ophthalmol 2016;171:27-34. Crossref

12. Hospital Authority. Cluster Presentation Programme—Kowloon Central Cluster. Eye Bank and Cornea Donation

Service in Hong Kong. 2021. Available from: https://www.ha.org.hk/haho/ho/cad_bnc/HAB-P310.pdf. Accessed 6

Jul 2021.

13. Lam NM, Rao SK, Young AL, Cheng LL, Lam DS.

Modified Osteo-Odonto Keratoprosthesis (MOOKP) in

patients with severe anterior segment disease: Our Hong

Kong Experience. ASCRS 2008. Chicago, United States

2008. Available from: http://ascrs2008.abstractsnet.com/handouts/000153_Modified_Osteo-Odonto_Keratoprosthesis_(MOOKP)_in_patients.ppt. Accessed 6 Jul 2021.

14. Kinoshita S, Koizumi N, Ueno M, et al. Injection of cultured

cells with a ROCK inhibitor for bullous keratopathy. N

Engl J Med 2018;378:995-1003. Crossref

15. Sarnicola C, Farooq AV, Colby K. Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy: update on pathogenesis and future directions. Eye Contact Lens 2019;45:1-10. Crossref