© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

REMINISCENCE: ARTEFACTS FROM THE HONG KONG MUSEUM OF MEDICAL SCIENCES

Dr Alice Hickling (1876-1928): the doctor

who changed the paradigm of maternal care in Hong Kong

Moira Chan-Yeung, FRCP, FRCPC

Member of the Education and Research Committee, Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences Society

Dr Alice Hickling was a pioneer in maternal and

infant health in Hong Kong. Born Alice Sibree, she

was a daughter of the Reverend Dr James Sibree, a

missionary and architect of the London Missionary

Society (LMS) in Madagascar. She studied at the

London School of Medicine for Women, received

special training in obstetrics and gynaecology at the

Rotunda Lying-in Hospital, Dublin, Ireland, and was

a licentiate of the Royal College of Physicians and

the Royal College of Surgeons, Edinburgh.1 She was

engaged by the LMS to direct the new Alice Memorial

Maternity Hospital (AMMH) in Hong Kong, which

was built using donations from the Chinese elite in

the community and was completed in 1904.

In the nineteenth century, both infant and

maternal mortality rates were very high in Hong

Kong. Although statistics were not routinely

recorded for maternal mortality or numbers of

live births, estimated infant mortality rates were

unbelievably high—from 700 to over 900 per 1000

births between 1895 to 1906.2 This high infant

mortality led to the appointment of a committee in

1903 to investigate the causes of infant deaths. On

the basis of findings that 50% of all infant deaths

were due to trismus as a result of tetanus infection

and the remainder due to other types of infection

and malnutrition, the committee recommended

more systematic registration of birth and deaths,

free maternity service to attend to confinement

of women in their own homes, training Chinese

midwives, and basic hygiene education for mothers.

The Colonial Administrator, Mr FH May, suggested

training Chinese midwives in the new AMMH.3

There were, however, problems with Mr. May’s

plan. When Western medicine was introduced in

Hong Kong, it was not accepted by the local Chinese

who trusted traditional Chinese medicine. Chinese

women had their confinement at home carried

out by traditional midwives (wan po), who learned

midwifery and delivery skills from oral tradition and

from attending childbirths with another wan po, and

who knew nothing about sepsis, one of the major

causes of maternal deaths.4 At that time Chinese

women would not see a Chinese male doctor let

alone a foreign male doctor. When the LMS asked Dr Ho Kai, who was responsible for raising funds to

build the new hospital, for more donations for the

salary of a doctor for the hospital, Dr Ho Kai and his

friends insisted on having a female doctor to care for

the Chinese women. However, Dr RM Gibson, the

Medical Superintendent of Alice Memorial Hospital,

the first of the Alice affiliated hospitals sponsored

by the LMS, insisted that women should be nurses

and not doctors, an opinion that was unfortunately

prevalent at the time.5 Another hurdle was the

stipulation that this female doctor appointed should

learn Cantonese during the first year after arrival, to

be able to communicate with the locals.

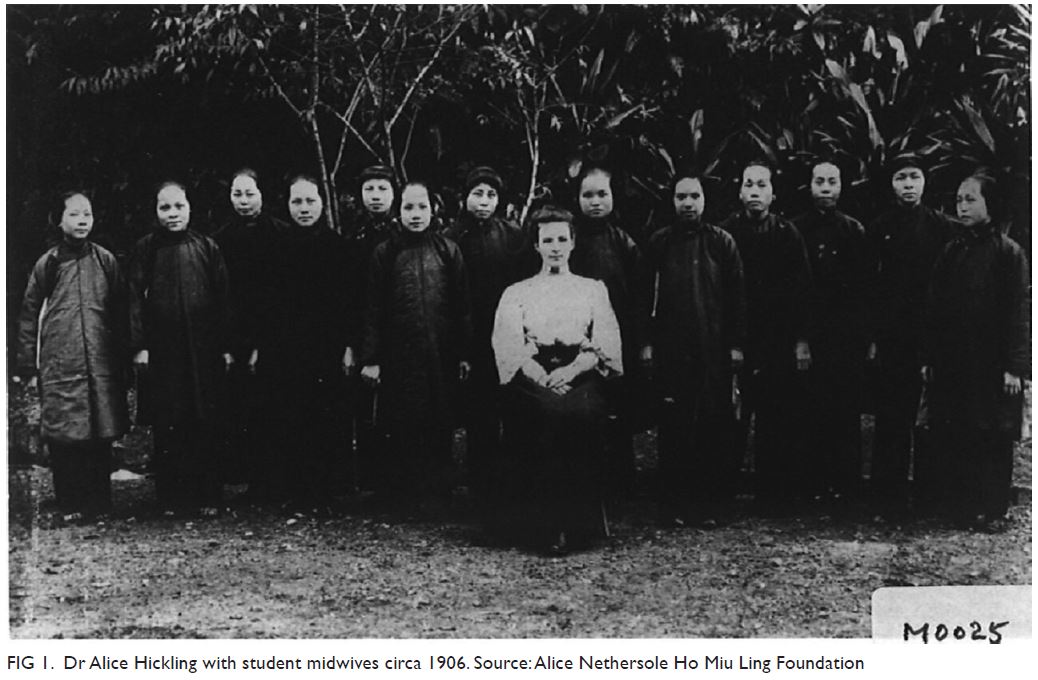

It was under these circumstances that Dr

Hickling entered the scene to become the first

female doctor in Hong Kong. Dr Hickling became

proficient in Cantonese within the first year, and as a

result, she was welcomed into the homes of Chinese

families to do her medical and missionary work. She

recommended that midwives receive formal training

in the Western style, following a 2-year course based

on the British curriculum. Student midwives had

to complete the general nursing training before

being admitted to this programme. The first three

student midwives she trained all passed the first

government examination for midwives held in 1906

and the government sent more midwives to AMMH

for training2 (Fig 1). By 1907, six trained midwives

were employed by the Chinese Public Dispensaries

and government clinics, and they attended to

579 domiciliary confinements that year.6 However,

Dr Hickling was not given any opportunities by Dr

Gibson to attend to general medical patients in the

Alice Memorial Hospital and out-patient clinics.

Instead, at the recommendation of Dr Ho Kai, she

took over maternity work at Tung Wah Hospital and

became the medical officer of Po Leung Kuk (the

Society for the Protection of Women and Children).

She also initiated a health education programme for

mothers after delivery on nutrition and general care

of infants in the hospitals.

Figure 1. Dr Alice Hickling with student midwives circa 1906. Source: Alice Nethersole Ho Miu Ling Foundation

Despite these challenges, by the end of her

contract in 1909, Dr Hickling’s services were much

sought after by Chinese women in the community.

The Chinese elite had been won over and they demanded the next female doctor should be on the

regular staff of the Alice hospitals and should take

charge of Chinese female patients under Western

treatment at Tung Wah Hospital.7

Dr Hickling returned to London at the end

of her contract and resigned from the LMS. On

returning to Hong Kong, she started her own

practice and served the Hong Kong community in

the secular setting. She continued to be responsible

for midwife training at AMMH, and in 1914, she

was appointed to the Midwives Board. She married

Mr CC Hickling, manager of Taikoo Sugar Refinery

in 1915. Dr Hickling became the first female doctor

to be appointed Acting Medical Officer of Health, in

1918, and Assistant Medical Officer in charge of all

Chinese hospitals and Chinese Public Dispensaries,

in 1922.8

When the Eastern District Plague Hospital was

converted into a maternity hospital in 1919, Dr Seen-wan

Ts’o and members of the Eastern District Public

Dispensary invited Dr Hickling to supervise the

hospital.9 The hospital grew quickly, handling close to

200 patients during its first year. When construction

was completed in 1922, Dr Hickling became director

of Tsan Yuk Hospital. At her suggestion, a midwife

training programme was established at the hospital

and the matron of the hospital was sent to attend a

course at Rotunda Hospital. From then, the teaching

of midwifery in Tsan Yuk Hospital was based on the principles of Rotunda Hospital. Dr Hickling also

established gynaecology clinics, a gynaecology ward,

and an operation theatre in Tsan Yuk Hospital. It

was thanks to these efforts that Professor Richard

Edwin Tottenham of the Department of Obstetrics

and Gynaecology at The University of Hong Kong,

gradually transferred the Department’s clinical,

teaching, and research activities to Tsan Yuk

Hospital. As a result, the hospital became not only

the training centre for midwives but also for medical

students and trainees in obstetrics and gynaecology.

Its low maternal mortality set a benchmark for other

maternity hospitals in Hong Kong.

Dr Hickling not only pioneered women’s

medical practice in Hong Kong, she also founded the

first “baby clinic”, precursor to the present Maternal

and Child Health Centres, to care for children aged

up to 2 years at Tsan Yuk Hospital. Other infant care centres were established, first at AMMH and Tung

Wah Hospital,7 then at outside hospitals in different

districts. These centres drew large numbers of

patients each year where babies were weighed and

examined and mothers given instruction in feeding

and care of babies and health education.

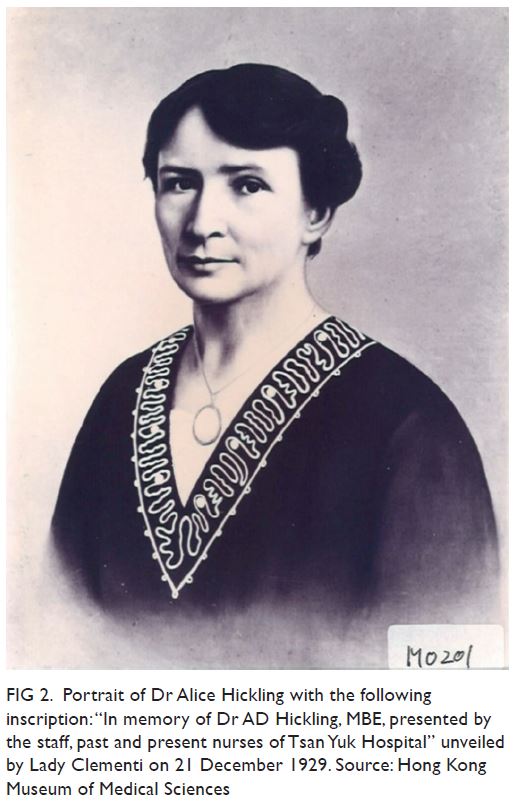

Dr Hickling was honoured with the Order of

the British Empire for her services during the First

World War, and received the decoration of Sister of

the Order of St John of Jerusalem. She died in Hong

Kong in September 1928.10 In commemoration of her

25 years of contributions to education and medical

and healthcare to women and infants, a portrait was

presented to Tsan Yuk Hospital by staff and past and

present nurses, to be hung in the Nurses’ Dining

Room. The portrait was unveiled by Lady Clementi

in the presence of Dr Seen-wan Ts’o and many

dignitaries of Hong Kong in December 1929 (Fig 2).

Figure 2. Portrait of Dr Alice Hickling with the following inscription: “In memory of Dr AD Hickling, MBE, presented by the staff, past and present nurses of Tsan Yuk Hospital” unveiled by Lady Clementi on 21 December 1929. Source: Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences

References

1. USC Digital Library. International Mission Photography Archive. Available from: http://digitallibrary.usc.edu/cdm/ref/collection/p15799coll123/id/48025. Accessed 20 Jun 2021.

2. Chow AW. Metamorphosis of Hong Kong midwifery. HKJGOM 2000;1:72-80. Crossref

3. May to Lyttelton, 21 July 1904, CO 129/323 #291, 240-3.

4. Medical Officer of Health. Report to the Sanitary Board, Hong Kong Sessional Papers. 1896 to 1907.

5. Editorial. The Lancet 1878;112:226-7.

6. Report of the Principal Chief Medical Officer and Medical Officer of Health for 1907. Hong Kong Sessional Papers, 1908, 409-10.

7. Minutes of Hong Kong District Committee Annual Meeting, 2 March 1909. London Missionary Society, Box 18, 1909, no 311.

8. The Late Dr Mrs Hickling. South China Morning Post 1929 Dec 1.

9. Chan-Yeung M. Eastern District (Wan Chai) Dispensary and Plague Hospital. Hong Kong Med J 2019;25:503-5. Crossref

10. Obituary: Dr Alice Deborah Hickling. Br Med J 1928;2:635-6. Crossref