© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

MEDICAL PRACTICE CME

Hong Kong Geriatrics Society and Hong Kong

Urological Association consensus on personalised management of male lower urinary tract symptoms in the era of multiple co-morbidities and polypharmacy

Peggy SK Chu, MB, BS, FRCS (Edin)1; Clarence LH Leung, MB, BS, FRCSEd (Urol)1; MH Cheung, MB, BS, FRCSEd (Urol)1; Sandy WS Woo, MB, BS, FHKCP2; TK Lo, MB, BS, FCSHK1; Tony NH Chan, MB, BS, FHKCP2; William KK Wong, MB, BS, FHKCP2

1 Hong Kong Urological Association, Hong Kong

2 The Hong Kong Geriatrics Society, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr TK Lo (ltk616@ha.org.hk)

Abstract

Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) are common

complaints of adult men. Benign prostatic hyperplasia

(BPH) represents the most common underlying

cause. As the incidence of BPH increases with age,

and pharmacological treatment is a major part of the

disease’s management, the majority of patients with

LUTS are managed by primary care practitioners.

There are circumstances in which specialist care

by urologists or geriatricians is required, such as

failure of medical treatment, adverse effects from

medical treatment, or complications from BPH.

Referral choices can be confusing to patients and

even practitioners in different specialties under such

circumstances. There is currently no local consensus

about the diagnosis, medical management, or

referral mechanism of patients with BPH. A

workgroup was formed by members of The Hong

Kong Geriatrics Society (HKGS) and the Hong Kong

Urological Association (HKUA) to review evidence

for the diagnosis and medical treatment of LUTS. A

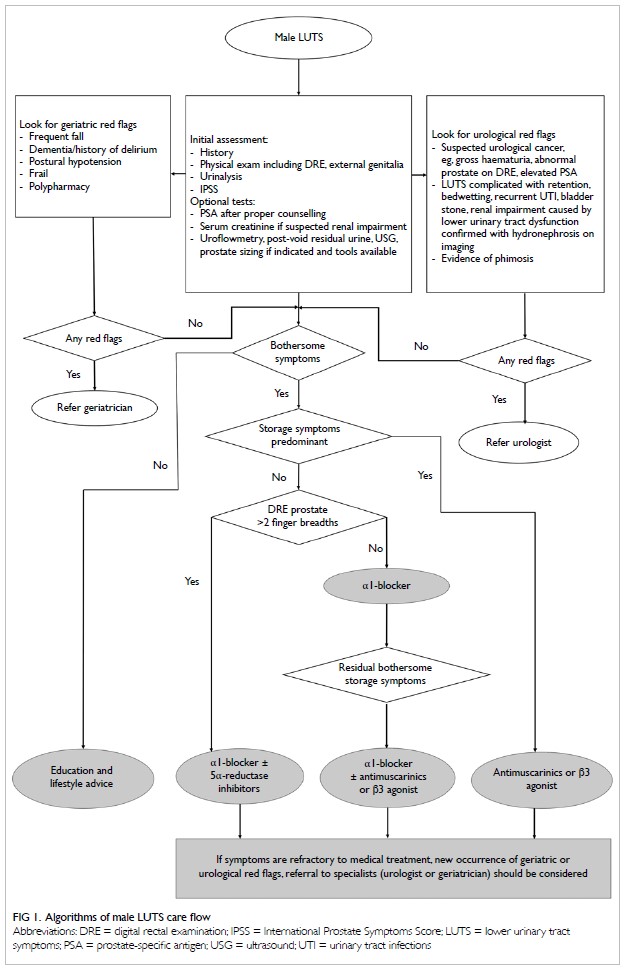

consensus was reached by HKGS and HKUA on an algorithm for the flow of male LUTS care and the

use of uroselective alpha blockers, antimuscarinics,

beta-3 adrenoceptor agonists, and 5α-reductase

inhibitors in the primary care setting. This consensus

by HKGS and HKUA provides a new management

paradigm of male LUTS.

Introduction

In 2019, Hong Kong overtook Japan as the region

with the world’s longest life expectancy, with the

life expectancy of Hong Kong Chinese men at

82.38 years.1 Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is

the most common prostate problem for men older

than 50 years. The occurrence of lower urinary tract

symptoms (LUTS) due to BPH increases with age.

A 1984 autopsy study showed that the prevalence of

BPH rose with each decade after age 40, peaking at

88% in men in their 80s.2 Since the 1980s, medical

therapy has been prescribed for patients with

bothersome LUTS that negatively affects their quality

of life. Moreover, the number of co-morbid diseases

also increases with age. Co-morbidity increases from

10% at ages up to 19 years to 80% at ages 80 years and

older.3 Co-morbidity also leads to polypharmacy and

drug-drug interactions, which may result in serious

adverse effects.

There is no established local consensus

regarding the management of elderly male patients with LUTS. Thus, the Hong Kong Geriatrics Society

(HKGS) and the Hong Kong Urological Association

(HKUA) formed a working group with the aim

of providing insights to clinicians involved in the

medical management of male patients with LUTS

through a consensus article.

Diagnostic evaluation

The causes of male LUTS can be multifactorial.

Detailed history, appropriate questionnaires,

physical examination, and investigation not only

help clinicians to reach a diagnosis and identify some

alarming conditions (eg, prostate cancer and bladder

cancer) but also guide treatment options and give

prognostic information for patients’ counselling.

History

It is useful to determine the most predominant and

bothersome LUTS to guide their management, eg,

voiding symptoms (weak stream, intermittency, hesitancy, incomplete emptying) and storage

symptoms (urgency, frequency, nocturia). The

severity of symptoms can be categorised by the

International Prostate Symptoms Score as mild (0-7),

moderate (8-19), or severe (20-35). It is a validated

tool for the assessment of symptoms and quality of

life in patients with LUTS (online supplementary Appendix) and allows objective monitoring of

treatment response.

Focused histories of the presence of

neurological diseases, diabetes mellitus, medication,

drinking habits, and prior lower urinary tract

procedures are useful to identify causes of LUTS

other than BPH (eg, neurogenic bladder, polydipsia,

urethral stricture).

Referral to geriatricians should be considered

in elderly patients with history of postural

hypotension, delirium, dementia, frequent falling, or

polypharmacy, as these patients have a higher risk

of adverse effects from medical treatment of LUTS,

and comprehensive geriatric assessment may be

necessary.

Alarming symptoms should raise suspicion of

pathologies other than BPH, eg, gross haematuria

or unexplained dysuria may imply underlying

neoplastic or inflammatory causes, or bedwetting

may imply underlying chronic urinary retention with

overflow incontinence. Prompt referral to urologists

is preferable in the presence of such symptoms.

Physical examination

Digital rectal examination is used to assess prostate

size, consistency, the presence of prostatic nodules,

and anal tone. In addition, focused examination of

the abdomen, external genitalia, and lower limbs is

important. Palpable bladder, phimosis, penile mass, and abnormal neurological signs are important to

notice when considering referral to appropriate

specialists.

A rough estimation of prostate size by number

of finger breaths on digital rectal examination is

acceptable and may guide the use of 5α-reductase

inhibitors (5ARi). Imaging assessment by ultrasound

can be considered if more accurate assessment is

preferred.

Investigations

Most patients with LUTS have slow deterioration

of symptoms, and very few develop complications

over a 5-year period.4 In the primary care setting,

the aim of initial evaluation is to detect non-BPH

causes, and urinalysis should be included. Prostate-specific

antigen (PSA) can be measured after proper

counselling, and serum creatinine should be checked

when renal impairment is suspected. Numerous

additional investigations are also possible, such as

flow rate measurement, post-void residual urine

volume, renal ultrasonography, prostate sizing,

or urodynamic study. However, these additional

investigations are optional and need not be routinely

performed at the initial evaluation, as they are not

cost-effective. Selected patients with appropriate

indications (eg, LUTS with poor response to

medical treatment, presence of alarming symptoms,

impaired renal function) benefit the most from these

tests, and input from specialists is preferred in these

circumstances.

Urinalysis

Urinalysis (dipstick or sediment count) should be

included in the primary evaluation of any patients

presenting with LUTS to search for urinary tract

infections, microscopic haematuria, and diabetes

mellitus. If abnormal findings are detected, further

tests are recommended.5

Prostate-specific antigen

One of the differential diagnoses of male LUTS is

prostate cancer. Prostate-specific antigen is organ-specific

but not cancer-specific. There is substantial

overlap in values between men with benign and

malignant prostate disease. Hence, elevated PSA

levels should be interpreted with caution.

For patients with abnormal DRE, checking PSA

can increase the detection rate of prostate cancer.

However, for patients with normal DRE, PSA should

be checked only when the detection of prostate cancer

will cause the disease’s management to be modified.

In general, in patients with life expectancy of <10

years or with multiple co-morbidities, checking of

PSA to detect prostate cancer might not be beneficial

to the patient and should only be performed with

special justification after proper counselling.

Serum creatinine

Assessment of renal function should be considered in

patients with high risk of renal impairment (eg, those

with multiple co-morbidities and polypharmacy).

Treatment

The majority of patients with LUTS have slow

progression of symptoms, with fewer than 2%

developing urinary retention and fewer than 10%

requiring BPH surgery over a 5-year period.4

Patients not bothered by their symptoms can be

safely managed conservatively with education and

lifestyle changes.6 Examples of lifestyle changes

include reduction of fluid intake before bedtime to

lessen nocturia, avoidance of caffeinated beverages

or alcohol to reduce frequency and urgency, urethral

milking to prevent post-micturition dribbling, and

optimising the timing of medication, especially

diuretics.

In addition to education and lifestyle changes,

medical treatment can be considered for patients

with bothersome symptoms. Voiding symptoms

can be regarded as the manifestation of underlying

bladder outlet obstruction resulting from BPH,

which underpins the rationale of using alpha-1

adrenoceptor antagonists (α1-blockers). Storage

symptoms can be attributed to either underlying

obstruction-induced change in bladder function

or overactive bladder without bladder outlet

obstruction. The choice of agent depends on the

predominant type of symptoms (ie, voiding vs

storage symptoms). For patients with predominant

voiding symptoms, the first-line medical treatment

is α1-blockers, which have been shown to improve

both voiding and storage symptoms.7 For patients

with predominant storage symptoms or residual

storage symptoms after a trial of α1-blockers,

antimuscarinics and beta-3 adrenoceptor agonist (β3

agonist) can be considered. For patients with large

prostate (eg, >40 cc), 5ARi can be used to reduce the

prostate size, improving symptoms and preventing

disease progression in terms of acute urinary

retention and future need of BPH surgery. It is

important to consider adverse effects before starting

medical treatment, especially in older patients with

multiple co-morbidities and polypharmacy.

Surgical treatment can be considered for

patients who develop BPH complications (eg, urinary

retention, bladder stones, obstructive uropathy,

recurrent urinary tract infection, haematuria) or

symptoms refractory to medical treatment. However,

surgery is associated with potential morbidities and

mortality, especially in frail geriatric patients.

Frailty is a syndrome characterised by reduced

physiological reserve and increased vulnerability

to adverse outcomes. Even minor stressor events

such as surgery can trigger disproportionate worsening of health status in frail elderly people.

The most frequently used model to identify frailty

is the phenotype described by Fried et al8 in 2001,

which comprises five variables: unintentional

weight loss, self-reported exhaustion, low energy

expenditure, slow gait speed, and weak grip

strength. The definition of polypharmacy has no

universally agreed cut-off point with regard to the

number of medications. Different researchers have

arbitrarily chosen various cut points. In the late

1990’s, the United States Centers for Medicare and

Medicaid Services implemented a quality indicator

measure that targets patients taking nine or more

concurrent medications. An alternative definition of

polypharmacy is the use of more medications than

are medically necessary.9

After commencement of medical therapy,

apart from the monitoring of treatment response

and adverse drug reactions, it is also crucial to review

medical conditions and identify the new occurrence

of geriatric red flags (eg, frailty, polypharmacy)

as patients age. The consensus algorithm on male

LUTS care flow in the primary care setting by HKGS

and HKUA is outlined in Figure 1.

Alpha-1 adrenoceptor antagonists

The use of α1-blockers has been shown to be

effective at reducing LUTS associated with BPH.5

The α1-blockers relax smooth muscle tone at the

bladder neck and prostate by blocking the action

of endogenously released noradrenaline.10 They are

usually considered as the first-line therapy for male

LUTS because of their good efficacy on symptomatic

relief but do not alter the natural progression of the

disease.

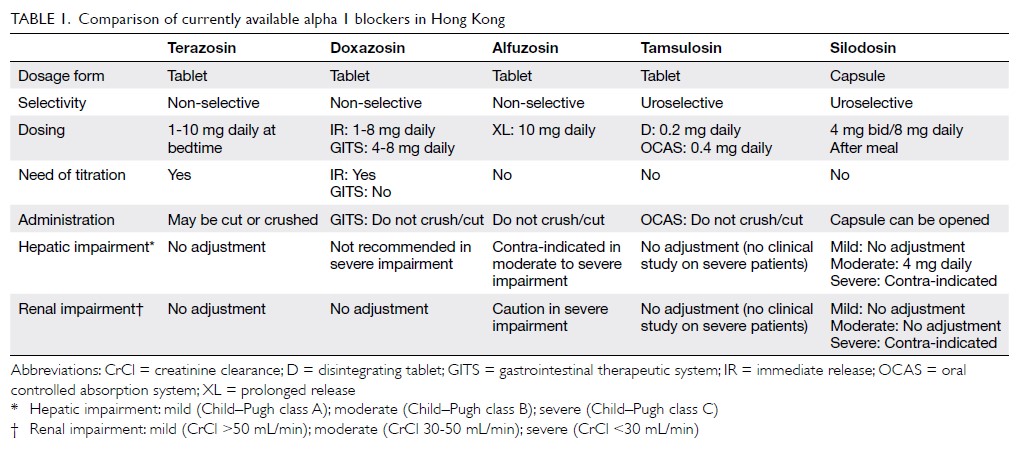

Currently available α1-blockers include

prazosin, terazosin, doxazosin, alfuzosin, tamsulosin

and silodosin. They have different uroselectivity,

pharmacokinetic properties, and formulations

(Table 1). Prazosin is a short-acting drug that requires

multiple dosing schedules and was the earliest drug

to be used for treatment of BPH. However, the

2003 American Urological Association Guidelines

concluded that there was insufficient support for

recommending prazosin as a treatment option for

LUTS secondary to BPH.11 These and the European

Association of Urology Guidelines regard prazosin

as a nonstandard treatment.

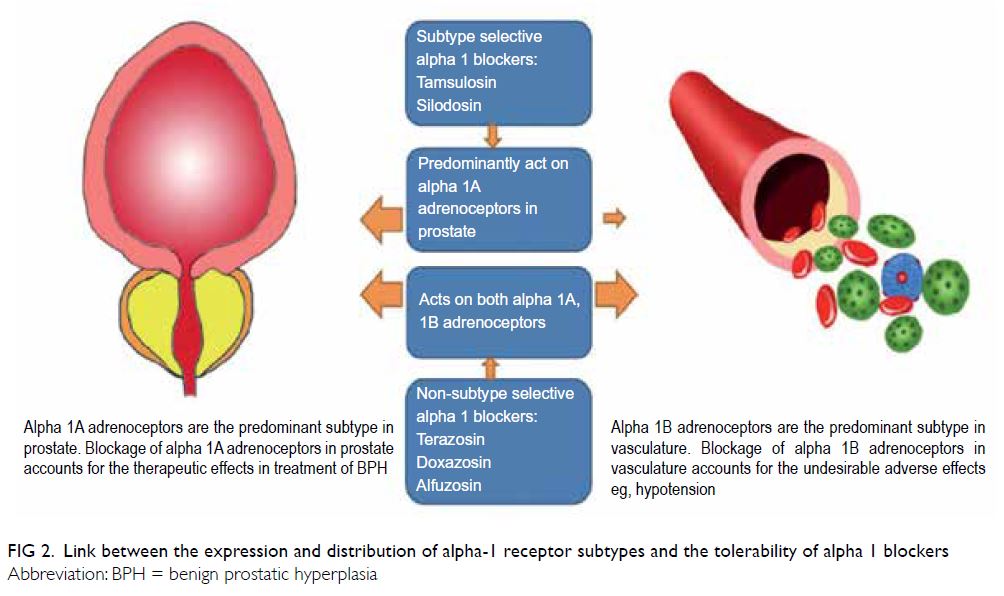

Although different α1-blockers have similar

efficacy in improving symptoms and uroflow

at appropriate doses, uroselective agents (α-1A

blockers) and long-acting preparations appeared

to be better tolerated. The differences between the

tolerability of various α1-blockers can be explained

by the differences in the expression and distribution

of receptor subtypes (alpha 1A and 1B) in the body

(Fig 2).

Figure 2. Link between the expression and distribution of alpha-1 receptor subtypes and the tolerability of alpha 1 blockers

Major adverse effects of α1-blocker use

include dizziness, asthenia, postural hypotension,

and syncope, which can result in falling (odds ratio

[OR]=1.14) and fractures (OR=1.16), especially in

elderly people,12 the majority of whom cannot tolerate

these drugs at the higher adult dose range. Studies

have consistently demonstrated that uroselective

agents including tamsulosin and silodosin have the

least effect on blood pressure and the lowest risk of

developing vascular-related events.7 13 14 However, a

minor but significant change in blood pressure and heart rate was observed with tamsulosin, whereas no

significant change was demonstrated with silodosin

compared with placebo in a randomised controlled

trial.15

There have been reports concerning the

association of α1-blockers (especially tamsulosin)

with intraoperative floppy iris syndrome,16 leading

to a high rate of complications during cataract

surgery, and it is suggested that ophthalmologists

be reminded so that they can take precautions.

Sexually active patients should be informed of the adverse effect of abnormal ejaculation, which was

another adverse reaction more commonly related

with tamsulosin (OR=8.58) and silodosin (OR=32.5),

and patients should be informed of the potential

implications.17

Patients who are naïve to α-blockers may

develop postural hypotension, known as the “first

dose phenomenon,” which is more pronounced with

non-selective α1-blockers during the first 8 weeks of

treatment. However, it should not be overlooked with

uroselective agents, and special precautions should

be taken, especially in elderly patients. In addition,

swallowing difficulties are not uncommon in elderly

patients, in whom modified release preparations are

inappropriate.

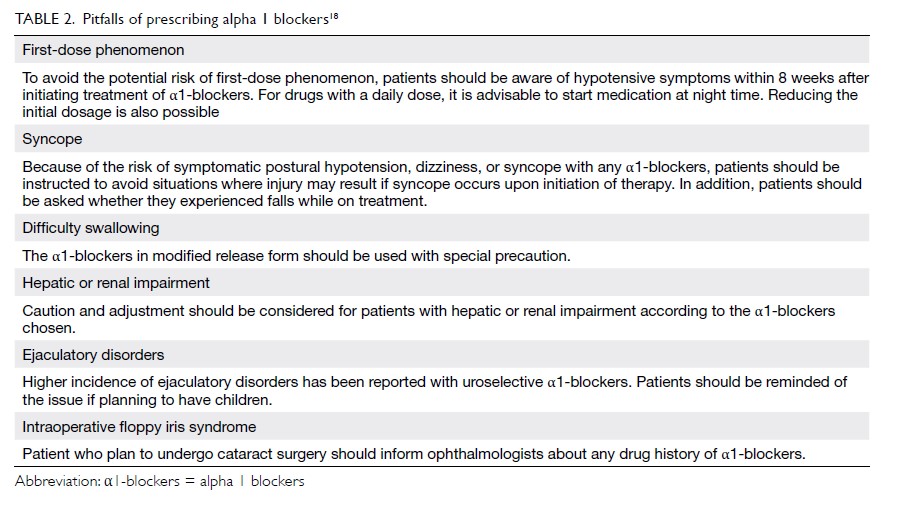

The pitfalls of prescribing α1-blockers are

summarised in Table 2.18 Their most troublesome

adverse effect is postural hypotension. The

situation is even more complicated if the patient

has concomitant hypertension or is taking multiple

medications with hypotensive effects for various

indications. It is estimated that more than 25% of

men aged >60 years have concomitant BPH and

hypertension,19 which poses a significant challenge

in the prescription of α1-blockers. Non-selective

α1-blockers have been available as antihypertensive

agents for over 40 years. They reduce blood pressure

by blocking postsynaptic alpha (mainly alpha-1B)

receptors, thereby inhibiting noradrenaline release

that induces vasoconstriction, resulting in dilatation

of arterioles and venules. Among all α1-blockers,

prazosin, terazosin, and doxazosin are approved for

the management of hypertension, whereas alfuzosin,

tamsulosin, and silodosin have minimal effect on

blood pressure.

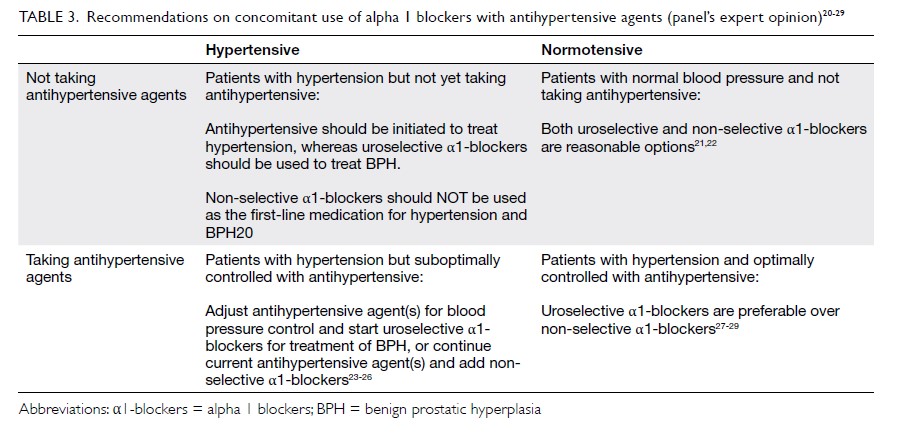

Because certain α1-blockers are approved

treatments for hypertension, they are a reasonable

choice for treatment of hypertensive men with

LUTS. However, with advances in hypertensive

treatment over past decades, the role of α1-blockers

in this context has changed, especially after the

introduction of uroselective agents. A consensus

was reached regarding revision of the use of

available safety data on α1-blockers in patients with

hypertension (Table 3).20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29

Table 3. Recommendations on concomitant use of α1-blockers with antihypertensive agents (panel’s expert opinion)20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29

Patients with hypertension but not yet taking

antihypertensive

For hypertensive LUTS patients who are not taking

any antihypertensives, we do not recommend the

use of non-selective α1-blockers for treatment

of BPH and hypertension together (first-line

treatment of hypertension). This recommendation

is based on the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial

Study.20 That study showed that compared with

chlorthalidone (diuretics), the use of doxazosin is

associated with significantly higher risk of stroke,

congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease,

angina, and cardiovascular disease requiring

coronary revascularisation. Multiple guidelines (The

Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC8) guideline30,

the European Society of Cardiology/the European

Society of Hypertension guideline31, the American

College of Cardiology/American Heart Association

guideline32 and Hypertension Canada’s 2017

guideline for diagnosis33) do not recommend α1-blockers as the first-line therapy for hypertension.

Therefore, we recommended treating LUTS with uroselective agents, and hypertension should be

treated with another class of antihypertensives

according to existing hypertension guidelines.

Patients with hypertension that

is suboptimally controlled with antihypertensive

For hypertensive LUTS patients who have

suboptimal blood pressure control but are taking

antihypertensive treatment, the addition of non-selective

α1-blockers (doxazosin gastrointestinal

therapeutic system [GITS] and terazosin) for

treatment of hypertension as second- or third-line

agents seems to be a reasonable option for achieving

optimal blood pressure control.23 24 25 26 However,

postural hypotension is a significant concern in the

treatment group. Therefore, although non-selective

α1-blockers are effective at reducing blood pressure

as add-on therapy, the risks and benefits of this

approach should be balanced and individualised.

This is the case especially when other classes of

antihypertensives may have additional benefits in

certain patients in whom treatment of LUTS with

uroselective agents and hypertension separately

with another class of antihypertensive agents might

be advisable.

Patients with normal blood pressure and not

taking antihypertensive

Among normotensive male patients aged >40 years

with LUTS who were not taking antihypertensives,

a multicentre study showed that doxazosin GITS

improved the International Prostate Symptoms

Score and the Quality of Life index with minimal effect on blood pressure.21 Another review of

α1-blockers’ effects on blood pressure showed

no significant changes in blood pressure in

normotensive patients irrespective of the type of

α1-blockers used (tamsulosin, alfuzosin, doxazosin

GITS, or terazosin).22 Therefore, it is reasonable to

consider either non-selective or uroselective α1-blockers in this group.

Patients with hypertension that is optimally

controlled with antihypertensive

The safety data on non-selective α1-blockers

in normotensive LUTS patients who are taking

antihypertensives with optimal blood pressure

control are largely based on post-hoc analysis of

randomised controlled trials assessing standard

versus intensive blood pressure control, which

involves non-selective α1-blockers as third- or

fourth-line antihypertensives. In the Action to

Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes trial,

which involved 10 251 high-risk participants

with type 2 diabetes mellitus at 77 centres, non-selective

α1-blockers were significantly associated

with postural hypotension, which was associated

with higher mortality and rates of heart failure

and hospitalisation.27 Another European study,

the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention trial,

which involved 9361 patients with increased

cardiovascular risk but without diabetes, found that

non-selective α1-blockers are associated with higher

risk of syncope and falling, although no significant

hypotensive events were demonstrated.28 Therefore,

we recommend the use of uroselective agents for

management of LUTS in this group of patients.

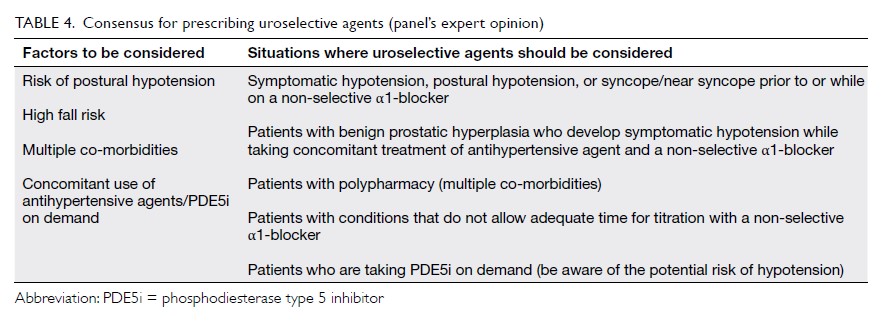

Apart from the risk of postural hypotension, the selection between non-selective and uroselective

agents should also be based on other factors,

including the risk of falling, polypharmacy, co-morbidities,

and specific situations where the use of

uroselective agents is advisable (Table 4).

Nevertheless, α1-blockers are effective

in relieving LUTS and improving quality of

life for patients with BPH. However, treatment

decisions should be individualised and based on

comprehensive assessment of patients with different

needs, especially in frail elderly patients, as they tend

to have accumulated co-morbidities, disabilities, and

polypharmacy that often interact with each other.

Antimuscarinics

Antimuscarinics are commonly used as

pharmacological treatments for overactive bladder.

This class of drug can also be used in predominant

or mixed storage LUTS. These drugs increase

bladder capacity and reduce urgency by blockading

the muscarinic receptor during bladder storage.34

Antimuscarinics have shown a modest benefit

over placebo in reducing urgency incontinence in

women.35 36 The efficacy of all the antimuscarinics

is similar.37 However, there is lack of head-to-head

comparison, and not all antimuscarinics

have been tested in elderly men. These drugs

often require higher doses to achieve the optimal

effects, and we recommend starting with the lowest

dose and titrating up as needed if the patient has

insufficient response and minimal adverse effects.

Antimuscarinics should be avoided if the patient

has clinically palpable bladder. These drugs can be

associated with increased post-void residual urine

volume after therapy, but acute retention is rare.5

Follow-up is recommended at 4 to 6 weeks to assess

therapeutic response and determine whether a

change in medication is necessary. Men should be

advised to discontinue medication if they develop

voiding difficulty, urinary infection, or worsening LUTS after initiation of therapy.

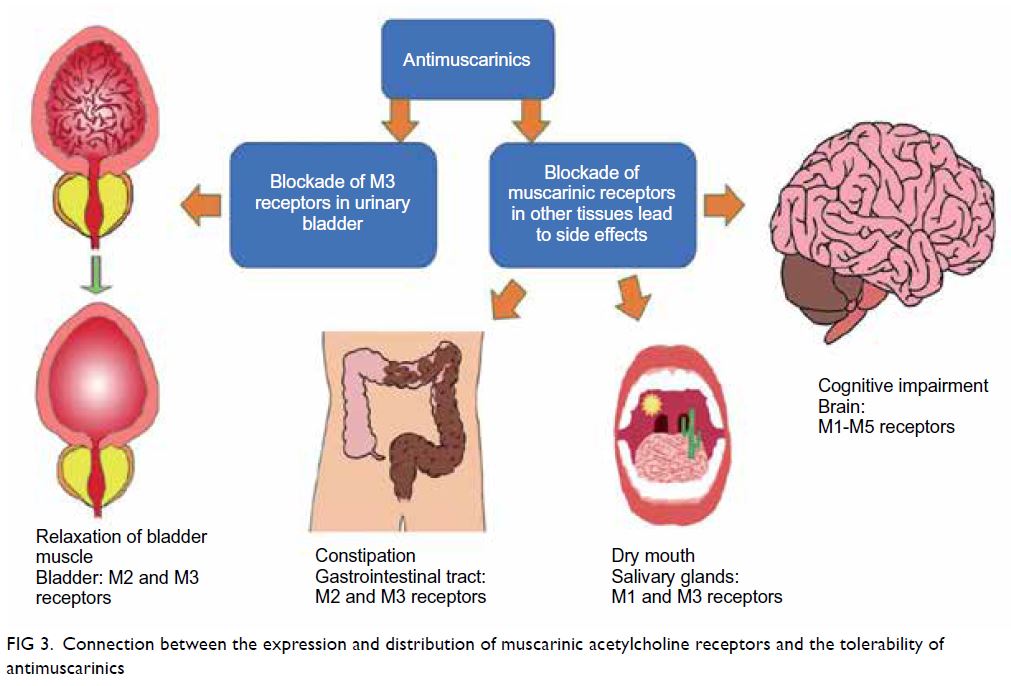

All antimuscarinics exert peripheral

anticholinergic effects that may limit drug tolerability

and dose escalation.35 Common adverse events

include dry mouth (up to 16%), constipation (up to

4%), dizziness (up to 5%), micturition difficulty (up

to 2%), blurred vision for near objects, tachycardia,

drowsiness, and worsened cognitive function.5 Up to

two-thirds of patients discontinue these medications

beyond 1 year.38 Constipation and compensatory

fluid intake for dry mouth may exacerbate urinary

incontinence. Patients with dementia are more

vulnerable to the adverse effects of antimuscarinics.39 40

Antimuscarinics should be avoided in patients

with uncontrolled tachyarrhythmia, myasthenia

gravis, and narrow angle-closure glaucoma. The

adverse effects of antimuscarinics can be explained

by the distribution of muscarinic acetylcholine

receptor subtypes throughout the body (Fig 3). The differences in tolerability between antimuscarinics

can be explained by their differences in selectivity

for receptor subtypes and tissue penetration.

Figure 3. Connection between the expression and distribution of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors and the tolerability of antimuscarinics

Antimuscarinics may have additive adverse

effects when combined with other medications that

have strong anticholinergic effects. They should be

used with caution or preferably avoided if elderly

patients are concomitantly taking other medications

with high anticholinergic potency, eg, first-generation

H1 antihistamines (chlorpheniramine,

hydroxyzine, diphenhydramine), anti-Parkinson’s

drugs (benztropine, trihexyphenidyl), spasmolytics

(atropine, hyoscine), anti-emetics (promethazine),

muscle relaxants, antipsychotics (chlorpromazine,

fluphenazine, trifluoperazine, clozapine), and tricyclic

antidepressants (amitriptyline, clomipramine,

doxepin, imipramine, nortriptyline).41 42 43

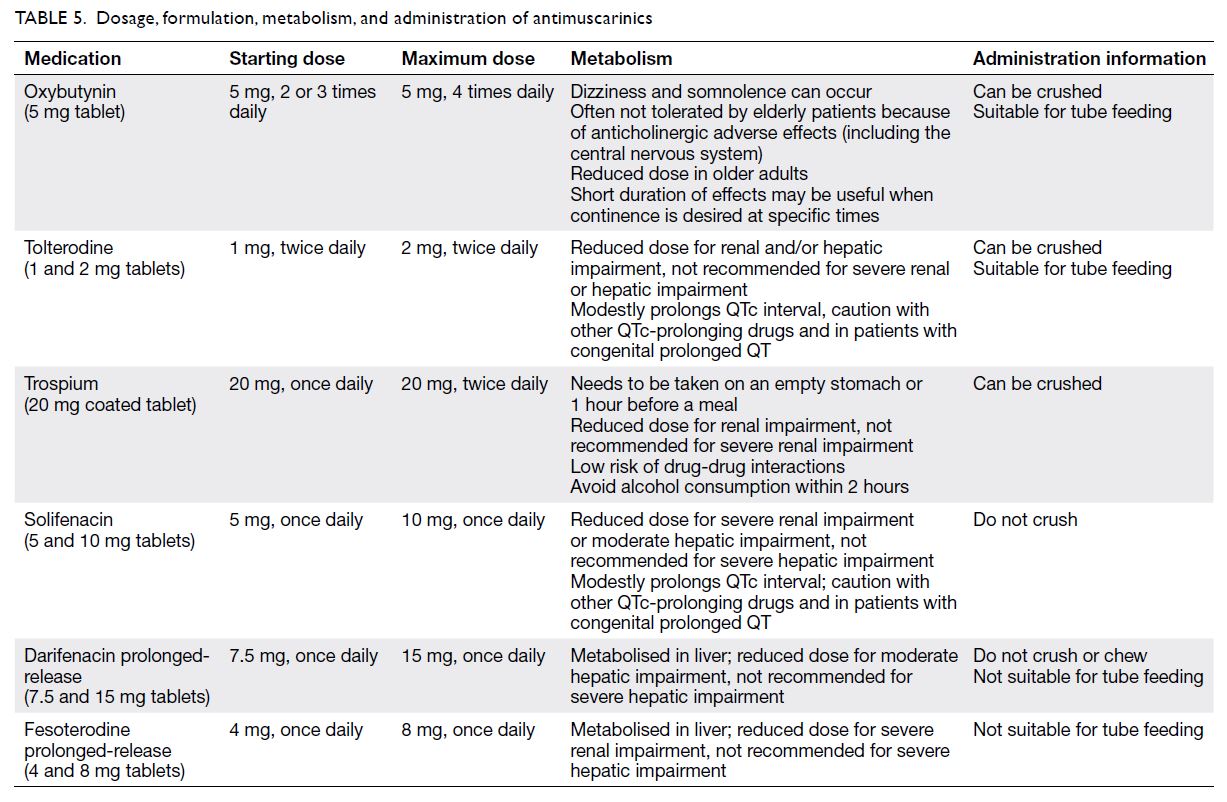

The antimuscarinics registered in Hong

Kong include oxybutynin, solifenacin, tolterodine,

trospium, darifenacin, and fesoterodine. Solifenacin,

darifenacin, and trospium may have less impact on

the central nervous system (Table 5).

Beta-3 adrenoceptor agonist

Beta-3 agonist is a new class of pharmacological

treatment used to relieve storage symptoms (urgency,

urinary frequency, and urge urinary incontinence)

associated with overactive bladder. It acts by binding

to the β3 adrenergic receptors on the bladder smooth

muscle causing bladder relaxation during the storage

phase. Mirabegron is currently the only approved β3

agonist for treatment of overactive bladder.

ln a phase III clinical trial, mirabegron 50 mg

daily resulted in a 50% reduction in the number of

urgency episodes per 24 hours and a 128% increase in

the mean volume voided per micturition compared

with placebo.44 Unlike antimuscarinics, it has

better tolerability with less dry mouth. In the study,

mirabegron’s incidence of dry mouth was similar to

that of placebo.45

Mirabegron has no influence on bladder

contraction during the voiding phase. In the clinical

trial, the incidence rate of acute urinary retention

was the lowest in mirabegron-treated patients

compared with the tolterodine and placebo groups

(0.1%, 0.6%, and 0.2%, respectively).44 The same trial

showed that mirabegron did not increase intraocular

pressure, and it is therefore not contra-indicated in

patients with glaucoma.

Regarding cardiovascular safety, the review

and real-world data on mirabegron did not show

any increased risk compared with conventional

antimuscarinics or in those with coexisting

cardiovascular disease.46 47 The European Association

of Urology guideline recommends β3 agonist as

a first-line medication for men with moderate-to-severe LUTS who have predominantly bladder

storage symptoms.48

Beta-3 agonist can be considered when

antimuscarinic adverse effects and high

anticholinergic burden are concerns, especially in

elderly adults with multiple co-morbidities and

cognitive impairment. Several studies have shown

that mirabegron is safe and effective in older

patients.49 50 51

The recommended dosage of mirabegron is

50 mg daily. For patients with renal impairment

(estimated glomerular filtration rate 15-29 mL/min/1.73 m2), Child–Pugh class B liver impairment, and

those aged ≥80 years with multiple co-morbidities,

25 mg daily should be considered. Mirabegron is not

recommended in patients with poorly controlled

hypertension (systolic blood pressure >180 mm Hg

or diastolic blood pressure >110 mm Hg), severe

renal impairment (estimated glomerular filtration

rate <15 mL/min/1.73 m2), or Child–Pugh class C

liver impairment. The most common adverse effects

reported were hypertension, nasopharyngitis, and

headache but the overall adverse event rates were

similar to those with placebo.52

5α-reductase inhibitors

5α-reductase is responsible for conversion of

testosterone to dihydrotestosterone, which has

an important role in prostate growth and the

development of BPH.53 There are two isoforms of

5α-reductase: type 1—the predominant enzyme in

extraprostatic tissue such as skin and liver; and type

2—the predominant enzyme in prostate (>90%),

which is critical to development of BPH.

The 5ARi drugs inhibit conversion of

testosterone to dihydrotestosterone, inducing

apoptosis and atrophy of prostatic epithelial cells.54

It results in reduction of prostate volume and hence

relief of bladder outflow obstruction. There are two

types of 5ARi: finasteride, which acts only on type

2 5α-reductase, and dutasteride, which acts on both

types. Meta-analysis has shown no differences in

efficacy or safety among these two drugs.55 56 There

are a few registered 5ARi drugs: Proscar (finasteride

5 mg), Avodart (dutasteride 0.5 mg), and Duodart

(combination of dutasteride 0.5 mg and tamsulosin

0.4 mg).

Long-term 5ARi treatment in patients with

moderate to severe LUTS and prostate volume

>40 cc has been shown to reduce the symptoms

score, risk of urinary retention, and risk of BPH-related

surgery. In a landmark study, patients taking

finasteride had improvement in symptoms and

uroflow, their prostate size reduced by 20%, their

risk of acute urinary retention reduced by 57%, and

their risk of BPH-related surgery reduced by 55%

compared with placebo after 4 years of treatment.56

There are some practical tips for prescribing

5ARi. First, the patient should have an enlarged

prostate >40 cc on ultrasound imaging. If ultrasound

is not readily available, it is acceptable to start 5ARi

treatment when the prostate size is greater than two

finger breadths on DRE. Second, it is important to

inform the patient that 5ARi have a slow onset of

action (3-6 months), as time is required for prostate

volume reduction. Continuous long-term treatment

should be expected. Third, the effects of 5ARis on PSA

levels should be explained to patients. The PSA level

is expected to be reduced by 50% after 6 to 12 months

of treatment,56 and therefore, good drug compliance

is required for proper interpretation of the PSA

level in prostate cancer screening. A persistent PSA

rise from the nadir in a patient on long-term 5ARi

treatment is an indicator for prostate biopsy, and

urological referral should be considered.57 Finally,

although some studies have suggested a higher

incidence of high-grade prostate cancer in patients

taking long-term 5ARi, no causal relationship has

been proven, and there is no difference in long-term

survival.58 The common adverse effects are

sexual dysfunction, such as decreased libido, erectile

dysfunction, and ejaculatory problems in around 4% to 8% and breast enlargement and tenderness in 1% of patients.56

Conclusion

Male LUTS is a common presentation to primary

care practitioners. Focused history and physical

examination are essential to differentiate BPH

from other causes of male LUTS and to guide its

management. Patients with minimal symptoms can

be managed conservatively, and pharmacological

treatments can be considered if symptoms are

bothersome. For patients with symptoms refractory

to pharmacological treatments or who have

complications (eg, urinary retention, obstructive

uropathy), surgical intervention can be performed

after assessment by urologists. With an ageing

population, geriatricians are adopting an increasing

role in the management of male patients with

LUTS in the era of multiple co-morbidities and

polypharmacy, as these patients are at higher risk

of adverse effects from pharmacological treatments

and are not optimal for surgical intervention. A

consensus has been reached by the HKGS and HKUA

regarding the diagnosis, evaluation, management,

and referral mechanism for LUTS in the primary

care setting. With collaboration between primary

care practitioners, geriatricians and urologists, we

hope that more holistic care can be provided to male

patients with LUTS in Hong Kong.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the concept or design of the study, acquisition of the data, analysis or interpretation of the

data, drafting of the manuscript, and critical revision of the

manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors

had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved

the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its

accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr CH Cheng for drawing the images in Figures 2 and 3; and Dr CW Man for his assistance in editing the

manuscript.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

1. United Nations Development Programme. Human

Development Report 2019. Beyond income, beyond

averages, beyond today: inequalities in human development

in the 21st century. 2019. Available from: http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/human-development-report-2019. Accessed 7 Jul 2020.

2. Berry SJ, Coffey DS, Walsh PC, Ewing LL. The development

of human benign prostatic hyperplasia with age. J Urol

1984;132:474-9. Crossref

3. van den Akker M, Buntinx F, Metsemakers JF, Roos S,

Knottnerus JA. Multimorbidity in general practice:

prevalence, incidence, and determinants of co-occurring

chronic and recurrent diseases. J Clin Epidemiol

1998;51:367-75. Crossref

4. Ball AJ, Feneley RC, Abrams PH. The natural history of untreated “prostatism”. Br J Urol 1981;53:613-6. Crossref

5. Gravas S, Cornu JN, Gacci M, et al. EAU Guidelines on management of non-neurogenic male LUTS. Arnhem, The Netherlands: EAU Guidelines Office; 2020.

6. Brown CT, Yap T, Cromwell DA, et al. Self management for men with lower urinary tract symptoms: randomised

controlled trial. BMJ 2007;334:25. Crossref

7. Djavan B, Marberger M. A meta-analysis on the efficacy and tolerability of alpha1-adrenoceptor antagonists in

patients with lower urinary tract symptoms suggestive of

benign prostatic obstruction. Eur Urol 1999;36:1-13. Crossref

8. Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci

Med Sci 2001;56:M146-56. Crossref

9. Tjia J, Velten SJ, Parsons C, Valluri S, Briesacher BA. Studies to reduce unnecessary medication use in frail older

adults: a systematic review. Drugs Aging 2013;30:285-307. Crossref

10. Michel MC, Vrydag W. Alpha1-, alpha2- and beta-adrenoceptors in the urinary bladder, urethra and prostate.

Br J Pharmacol 2006;147 Suppl 2:S88-119. Crossref

11. AUA Practice Guidelines Committee. AUA guideline

on management of benign prostatic hyperplasia (2003).

Chapter 1: Diagnosis and treatment recommendations. J

Urol 2003;170:530-47. Crossref

12. Welk B, McArthur E, Fraser LA, et al. The risk of fall

and fracture with the initiation of a prostate-selective

α antagonist: a population based cohort study. BMJ

2015;351:h5398. Crossref

13. Djavan B, Chapple C, Milani S, Marberger M. State of the

art on the efficacy and tolerability of alpha1-adrenoceptor

antagonists in patients with lower urinary tract symptoms

suggestive of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urology

2004;64:1081-8. Crossref

14. Morgia G. Does the use of silodosin to treat benign

prostatic hyperplasia really offer something new? Eur Urol

2011;59:353-5. Crossref

15. Chapple CR, Montorsi F, Tammela TL, et al. Silodosin

therapy for lower urinary tract symptoms in men with

suspected benign prostatic hyperplasia: results of an

international, randomized, double-blind, placebo- and

active-controlled clinical trial performed in Europe. Eur

Urol 2011;59:342-52. Crossref

16. Storr-Paulsen A, Nørregaard JC, Børme KK, Larsen AB,

Thulesen J. Intraoperative floppy iris syndrome (IFIS): a

practical approach to medical and surgical considerations

in cataract extractions. Acta Ophthalmol 2009;87:704-8. Crossref

17. Gacci M, Ficarra V, Sebastianelli A, et al. Impact of medical

treatments for male lower urinary tract symptoms due

to benign prostatic hyperplasia on ejaculatory function:

a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sex Med

2014;11:1554-66. Crossref

18. United States Department of Veterans Affairs. Pharmacy

Benefits Management Services, Medical Advisory Panel,

VISN Pharmacist Executives. Alfuzosin, silodosin, tamsulosin/clinically uroselective alpha1-adrenergic

blockers: recommendations for use. 2010. Available

from: https://www.pbm.va.gov/PBM/clinicalguidance/clinicalrecommendations/Alpha_Blockers_(Clinically_Uroselective_Alfuzosin_Silodosin_Tamsulosin)_Clinical_Recommendations.pdf. Accessed 27 Nov 2019.

19. Boyle P, Napalkov P. The epidemiology of benign

prostatic hyperplasia and observations on concomitant

hypertension. Scand J Urol Nephrol Suppl 1995;168:7-12. Crossref

20. ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group [editorial]. Major

cardiovascular events in hypertensive patients randomized

to doxazosin vs chlorthalidone: the antihypertensive and

lipid-lowering treatment to prevent heart attack trial

(ALLHAT). JAMA 2000;283:1967-75. Crossref

21. Dahlöf B, Sever PS, Poulter NR, et al. Prevention of

cardiovascular events with an antihypertensive regimen of

amlodipine adding perindopril as required versus atenolol

adding bendroflumethiazide as required, in the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial-Blood Pressure

Lowering Arm (ASCOT-BPLA): a multicentre randomised

controlled trial. Lancet 2005;366:895-906. Crossref

22. Lowe FC, Olson PJ, Padley RJ. Effects of terazosin therapy

on blood pressure in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia

concurrently treated with other antihypertensive

medications. Urology 1999;54:81-5. Crossref

23. Chung BH, Hong SJ. Long-term follow-up study to evaluate

the efficacy and safety of the doxazosin gastrointestinal

therapeutic system in patients with benign prostatic

hyperplasia with or without concomitant hypertension.

BJU Int 2006;97:90-5. Crossref

24. Lee SH, Park KK, Mah SY, Chung BH. Effects of α-blocker

‘add on’ treatment on blood pressure in symptomatic

BPH with or without concomitant hypertension. Prostate

Cancer Prostatic Dis 2010;13:333-7. Crossref

25. Black HR, Keck M, Meredith P, Bullen K, Quinn S, Koren A.

Controlled-release doxazosin as combination therapy

in hypertension: the GATES study. J Clin Hypertens

(Greenwich) 2006;8:159-66. Crossref

26. de Alvaro F, Hernández-Presa MA, ASOCIA Study.

Effect of doxazosin gastrointestinal therapeutic system

on patients with uncontrolled hypertension: the ASOCIA

Study. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 2006;47:271-6. Crossref

27. Fleg JL, Evans GW, Margolis KL, et al. Orthostatic

hypotension in the ACCORD (Action to Control

Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes) blood pressure trial:

prevalence, incidence, and prognostic significance.

Hypertension 2016;68:888-95. Crossref

28. SPRINT Research Group; Wright JT Jr, Williamson JD, et al.

A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure

control. N Engl J Med 2015;373:2103-16. Crossref

29. Hiremath S, Ruzicka M, Petrcich W, et al. Alpha-blocker use and the risk of hypotension and hypotension-related

clinical events in women of advanced age. Hypertension

2019;74:645-51. Crossref

30. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based

guideline for the management of high blood pressure

in adults: report from the panel members appointed to

the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA

2014;311:507-20. Crossref

31. Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, et al. 2018 ESC/ESH

Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension:

The Task Force for the management of arterial

hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology and the European Society of Hypertension: The Task Force for

the management of arterial hypertension of the European

Society of Cardiology and the European Society of

Hypertension. J Hypertens 2018;36:1953-2041. Crossref

32. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/

AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection,

Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in

Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical

Practice Guidelines. Hypertension 2018;71:e13-e115. Crossref

33. Leung AA, Daskalopoulou SS, Dasgupta K, et al.

Hypertension Canada’s 2017 Guidelines for Diagnosis, Risk

Assessment, Prevention, and Treatment of Hypertension

in Adults. Can J Cardiol 2017;33:557-76. Crossref

34. Finney SM, Andersson KE, Gillespie JI, Stewart LH.

Antimuscarinic drugs in detrusor overactivity and the

overactive bladder syndrome: motor or sensory actions?

BJU Int 2006;98:503-7. Crossref

35. Shamliyan T, Wyman JF, Ramakrishnan R, Sainfort F, Kane

RL. Benefits and harms of pharmacologic treatment for

urinary incontinence in women: a systematic review. Ann

Intern Med 2012;156:861-74. Crossref

36. Reynolds WS, McPheeters M, Blume J, et al. Comparative

effectiveness of anticholinergic therapy for overactive

bladder in women: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Obstet Gynecol 2015;125:1423-32. Crossref

37. Qaseem A, Dallas P, Forciea MA, et al. Nonsurgical

management of urinary incontinence in women: a

clinical practice guideline from the American College of

Physicians. Ann Intern Med 2014;161:429-40. Crossref

38. Brostrøm S, Hallas J. Persistence of antimuscarinic drug use. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;65:309-14. Crossref

39. Coupland CA, Hill T, Dening T, Morriss R, Moore M,

Hippisley-Cox J. Anticholinergic drug exposure and the

risk of dementia: a nested case-control study. JAMA Intern

Med 2019;179:1084-93. Crossref

40. Fox C, Richardson K, Maidment ID, et al. Anticholinergic

medication use and cognitive impairment in the older

population: the medical research council cognitive function

and ageing study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2011;59:1477-83. Crossref

41. Durán CE, Azermai M, Vander Stichele RH. Systematic review of anticholinergic risk scales in older adults. Eur J

Clin Pharmacol 2013;69:1485-96. Crossref

42. Salahudeen MS, Hilmer SN, Nishtala PS. Comparison of

anticholinergic risk scales and associations with adverse

health outcomes in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc

2015;63:85-90. Crossref

43. American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update

Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2015 updated

Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use

in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015;63:2227-46. Crossref

44. Chapple CR, Cardozo L, Nitti VW, Siddiqui E, Michel MC. Mirabegron in overactive bladder: a review of efficacy,

safety, and tolerability. Neurourol Urodyn 2014;33:17-30. Crossref

45. Khullar V, Amarenco G, Angulo JC, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of mirabegron, a β(3)-adrenoceptor agonist, in

patients with overactive bladder: results from a randomised

European-Australian phase 3 trial. Eur Urol 2013;63:283-

95. Crossref

46. Rosa GM, Ferrero S, Nitti VW, Wagg A, Saleem T,

Chapple CR. Cardiovascular safety of β3-adrenoceptor

agonists for the treatment of patients with overactive bladder syndrome. Eur Urol 2016;69:311-23. Crossref

47. Katoh T, Kuwamoto K, Kato D, Kuroishi K. Real-world

cardiovascular assessment of mirabegron treatment

in patients with overactive bladder and concomitant

cardiovascular disease: results of a Japanese post-marketing

study. Int J Urol 2016;23:1009-15. Crossref

48. Burkhard FC, Bosch JL, Cruz F, et al. EAU Guidelines on

urinary incontinence in adults. Arnhem, The Netherlands:

EAU Guidelines Office; 2016.

49. Wagg A, Staskin D, Engel E, Herschorn S, Kristy RM,

Schermer CR. Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of mirabegron

in patients aged ≥65yr with overactive bladder wet: a phase

IV, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled study

(PILLAR). Eur Urol 2020;77:211-20. Crossref

50. Makhani A, Thake M, Gibson W. Mirabegron in the

treatment of overactive bladder: safety and efficacy in thehttps://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S174402

very elderly patient. Clin Interv Aging 2020;15:575-81. Crossref

51. Lee YK, Kuo HC. Safety and therapeutic efficacy of

mirabegron 25 mg in older patients with overactive

bladder and multiple comorbidities. Geriatr Gerontol Int

2018;18:1330-3. Crossref

52. Tubaro A, Batista JE, Nitti VW, et al. Efficacy and safety of

daily mirabegron 50 mg in male patients with overactive

bladder: a critical analysis of five phase III studies. Ther Adv Urol 2017;9:137-54. Crossref

53. Carson C 3rd, Rittmaster R. The role of dihydrotestosterone

in benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urology 2003;61(4 Suppl

1):2-7. Crossref

54. Rittmaster RS, Norman RW, Thomas LN, Rowden G.

Evidence for atrophy and apoptosis in the prostates of men

given finasteride. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1996;81:814-9. Crossref

55. Jun JE, Kinkade A, Tung AC, Tejani AM. 5α-reductase

inhibitors for treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia: a

systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Hosp Pharm

2017;70:113-9. Crossref

56. Roehrborn CG, Boyle P, Bergner D, et al. Serum prostatespecific

antigen and prostate volume predict long-term

changes in symptoms and flow rate: results of a four-year,

randomized trial comparing finasteride versus placebo.

PLESS Study Group. Urology 1999;54:662-9. Crossref

57. Marks LS, Andriole GL, Fitzpatrick JM, Schulman CC,

Roehrborn CG. The interpretation of serum prostate

specific antigen in men receiving 5alpha-reductase

inhibitors: a review and clinical recommendations. J Urol

2006;176:868-74. Crossref

58. Thompson IM Jr, Goodman PJ, Tangen CM, et al. Longterm

survival of participants in the prostate cancer

prevention trial. N Engl J Med 2013;369:603-10. Crossref