Hong Kong Med J 2021 Feb;27(1):70–2 | Epub 2 Feb 2021

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

COMMENTARY

COVID-19 primary care response and challenges

in Singapore: a tale of two curves

Y Liow, MB, BS, MMed1,2; Victor WK Loh, MMed, MHPE2; LH Goh, MB, BS, MMed2; David HY Tan, MB, BS, MMed1,2 TL Tan, FRCPE, FCFPS2,3; CK Leong, MMed, FAMS2,4; Doris YL Young, MB, BS, MD2

1 National University Polyclinics, National University Health System, Singapore

2 Division of Family Medicine, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore

3 The Edinburgh Clinic, Singapore

4 Mission Medical Clinic, Singapore

Corresponding author: Dr Y Liow (yiyang_liow@nuhs.edu.sg)

Introduction

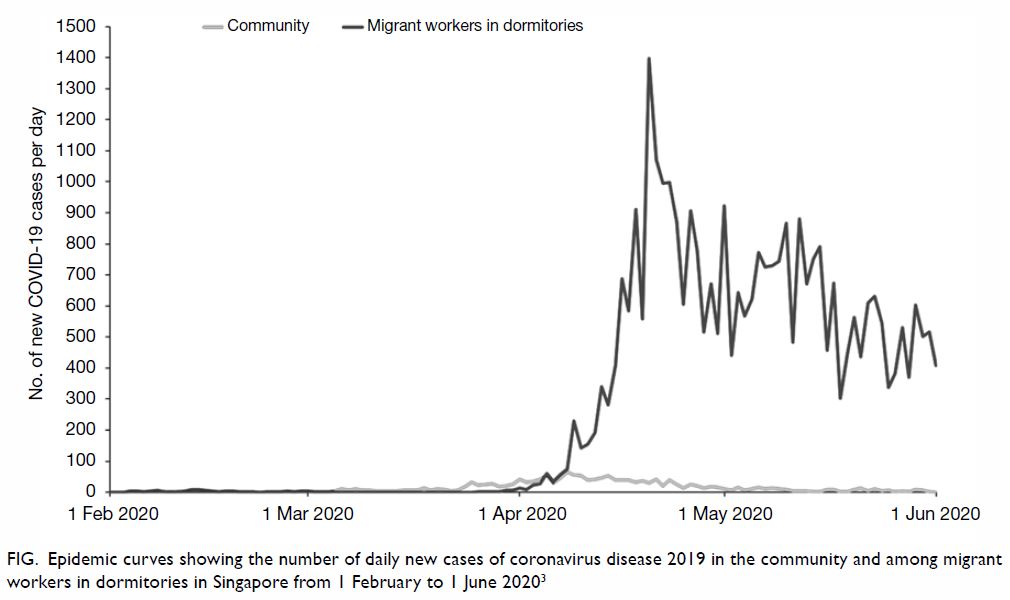

As global cities with comparable healthcare systems

and shared experience of the 2003 Severe Acute

Respiratory Syndrome outbreak, Hong Kong

and Singapore have had contrasting fortunes in

flattening their respective coronavirus disease

2019 (COVID-19) epidemic curves. Both reported

their first cases 1 day apart in late January 2020 and

quickly implemented border entry restrictions and

quarantine orders to limit imported cases. Hong

Kong adopted other aggressive interventions such as

school closures,1 whereas Singapore opted for a more

measured initial approach that included advising

only those unwell to wear face masks.2 Hong Kong

flattened its curve by the end of March; despite early

success, Singapore grappled with the emergence of

two distinct curves: one representing the Singapore community population and another representing the

migrant worker dormitory population (Fig3). This

commentary presents the duality of the COVID-19

situation in Singapore and discusses the related

primary care response and challenges.

Figure. Epidemic curves showing the number of daily new cases of coronavirus disease 2019 in the community and among migrant workers in dormitories in Singapore from 1 February to 1 June 20203

Primary care in Singapore

Located in Southeast Asia, Singapore is an island

city-state with a population of more than 5.7 million.

Primary care forms the foundation of its healthcare

system. Similar to Hong Kong, the majority (about

80%) of primary care services are provided by 1700

privately run clinics, which range from sole proprietor

to large group practices. The remaining demand

is met by 20 community-based healthcare centres

known as ‘polyclinics’, which are similar to General

Outpatient Clinics in Hong Kong. These operate with government subvention to provide subsidised care

based on citizenship status.4 Whereas the private

sector handles almost 90% of acute visits, polyclinics

see more than 40% of chronic disease attendances.5

Community curve

When local transmission was detected in Singapore in

early February 2020, authorities activated the Public

Health Preparedness Clinics (PHPC), an island-wide

network of more than 900 primary care clinics and

polyclinics. Patients with acute respiratory symptoms

received subsidised treatments at these clinics, which

increased accessibility to care. This resulted in more

than 70% of confirmed cases visiting a clinic within

2 days of symptom onset.6 Those who met suspect

case criteria were tested under the ‘Swab-and-Send-Home’ (SASH) programme. The SASH facilitated out-patient

management, increased testing capacity, and

reduced the burden on tertiary centres. The network

also served an epidemiological role by gathering data

on community transmission including performing

sentinel surveillance swabs. Together with other

public health measures and the ‘circuit breaker’,

which was an enhanced set of social distancing

measures introduced by the Singapore Government

in early April including closure of schools and non-essential

workplaces, the PHPC helped to flatten the

community curve by end May 2020.7

The immediate challenge faced by primary care

physicians from the PHPC was introducing infection

control measures, including creating segregation

protocols and well-ventilated isolation areas. These

were operational challenges, particularly for smaller

practices with limited resources. A global shortage

of personal protective equipment also meant that

clinics had to ration supplies. Keeping abreast of new

advisories and workflows was another challenge. For

instance, SASH was initially restricted to patients

with clinical or radiological features of community-acquired

pneumonia. However, as evidence emerged

of pre-symptomatic transmission8 and mild disease

in the early stages, the SASH criteria were expanded

accordingly. At activated PHPC centres, physicians

encountered patients who had visited other clinics

and had not improved. More than 20% of the first

160 confirmed cases visited more than one clinic.9

‘Doctor hopping’ disrupted continuity of care

and risked cross contamination between clinics.

Proper messaging through mainstream and social

media channels helped reduce such behaviour.10 As

COVID-19 emerged, cases of dengue fever, which is

endemic in Singapore, were at a 4-year high.11 Both

viral infections have significant overlap in clinical and

laboratory features.6 Primary care physicians had to

be mindful of this dual outbreak as well as ‘covert’

COVID-19 masquerading as false-positive dengue

serology.12

Migrant worker dormitory curve

Originating mainly from India, Bangladesh, and

China, migrant workers in Singapore are employed in

industries such as construction and manufacturing.

There are about 323 000 residing in close proximity

to each other in 43 purpose-built dormitories.13

Worksites often engage workers living in different

dormitories and hence a single case can lead to

multiple clusters. Despite precautions taken to

restrict socialisation, more than 35 000 such workers

have been infected. Outposts in dormitories were

erected to screen workers and meet their medical

needs. Facilities island-wide including hotels and

exhibition centres were converted to isolation centres

to house those affected. Primary care physicians, who

are trained to provide care across multiple settings in

the community, were mobilised to these sites. Many

from public and private sectors, as well as locum and

retired practitioners, volunteered their efforts. Some

brought essential experience, having previously cared

for migrant workers as designated workplace doctors

or practising in industrial areas and non-profit clinics

catered to migrant workers.

One of the first challenges faced by primary

care physicians delivering care on-site was the

language barrier. Many workers spoke little or no

English, the working language of Singapore, which

impaired communication. Physicians overcame this

through visual aids, translators, and smartphone

applications.14 Although the majority of workers

are young and healthy, some are middle-aged with

chronic conditions such as hypertension and diabetes

mellitus. Some were being managed by physicians in

their home countries with care invariably affected by

disruption due to the pandemic. These conditions

had to be managed carefully with given resources.

The workers’ mental health also had to be monitored

closely with concerns of ‘cabin fever’ from prolonged

isolation progressing to more serious depressive and

anxiety disorders. New cases are still being recorded

daily and with authorities’ plans to test every worker,

primary care physicians will continue playing an

important role in flattening this curve.15

Conclusion

Singapore’s tale of two curves has important lessons.

Firstly, containment and mitigation strategies are

effective in flattening COVID-19 epidemic curves.16

As borders and economies reopen, measures with

the most benefit and least cost to society may need

reinstating. Secondly, accessible and coordinated

primary care continues to be a key arm of the

response to public health emergencies. Authorities

must continue to engage physicians and other

stakeholders regularly and should do so even during

‘peace time’. Lastly, every precaution must be taken to protect groups who live communally, such as migrant

workers. Singapore must look again at how these

workers are housed. The magnitude of the dormitory

curve should be a stark warning to other nations with

similar groups.

Author contributions

Concept or design: Y Liow, WKV Loh, DYL Young.

Acquisition of data: Y Liow.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: All authors.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: Y Liow.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: All authors.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take

responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Ms Monica Ashwini Lazarus, Department of Family Medicine, Yong Loo Lin School of

Medicine, National University of Singapore, for editing a draft

of this manuscript.

Funding/support

The authors received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors, in relation to this commentary.

References

1. Cowling BJ, Ali ST, Ng TW, et al. Impact assessment of

non-pharmaceutical interventions against coronavirus

disease 2019 and influenza in Hong Kong: an observational

study. Lancet Public Health 2020;5:e279-88. Crossref

2. Goh T. Wuhan virus: Masks should be used only by those

who are unwell. The Straits Times. 31 Jan 2020. Available

form: https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/health/masks-should-be-used-only-by-those-who-are-unwell.Accessed 31 Jan 2020.

3. Ministry of Health, Singapore Government. COVID-19

interactive situation report. 2020. Available from: https://www.moh.gov.sg/covid-19/situation-report. Accessed 9

Jun 2020.

4. Ministry of Health, Singapore Government. Primary

healthcare services. 2018. Available from: https://www.moh.gov.sg/home/our-healthcare-system/healthcare-services-and-facilities/primary-healthcare-services. Accessed 9 Jun 2020.

5. Ministry of Health, Singapore Government. Primary Care

Survey 2014 Report. Available from: https://www.moh.gov.sg/resources-statistics/reports/primary-care-survey-2014-report. Accessed 8 Jun 2020.

6. Lam LT, Chua YX, Tan DH. Roles and challenges of

primary care physicians facing a dual outbreak of

COVID-19 and dengue in Singapore. Fam Pract

2020;37:578-9. Crossref

7. Ministry of Health, Singapore Government. Circuit

breaker to minimise further spread of COVID-19. 3 Apr

2020. Available from: https://www.moh.gov.sg/news-highlights/details/circuit-breaker-to-minimise-further-spread-of-covid-19. Accessed 9 Jun 2020.

8. Wei WE, Li Z, Chiew CJ, Yong SE, Toh MP, Lee VJ. Presymptomatic transmission of SARS-CoV-2–Singapore,

January 23-Mar 16, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep

2020;69:411-5. Crossref

9. Singapore Government. COVID-19 spread caused by

socially irresponsible behaviour. 11 Mar 2020. Available from: https://www.gov.sg/article/covid-19-spread-caused-by-socially-irresponsible-behaviour. Accessed 9 Jun 2020.

10. Singapore Government. Steps to take when you’re unwell.

23 Mar 2020. Available from: https://www.gov.sg/article/steps-to-take-when-youre-unwell. Accessed 9 Jun 2020.

11. Ng JS. Dengue cases at four-year high. Today Online.

Available from: https://www.todayonline.com/singapore/dengue-cases-four-year-high. Updated 12 Feb 2020. Accessed 11 Feb 2020.

12. Yan G, Lee CK, Lam LT, et al. Covert COVID-19 and falsepositive

dengue serology in Singapore. Lancet Infect Dis

2020;20:536. Crossref

13. Ministry of Manpower, Singapore Government. List

of foreign worker dormitories. 2020. Available from:

https://www.mom.gov.sg/passes-and-permits/work-permit-

for-foreign-worker/housing/foreign-workerdormitories#/?page=1&q. Accessed 9 Jun 2020.

14. Yip C. ‘Your website will save lives’: NUS graduate builds

translation portal for medical teams treating migrant

workers. Channel News Asia: International Edition.

CNA Insider. 17 Apr 2020. Available from: https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/cnainsider/covid-19-nus-medical-graduate-bengali-translators-workers-12650406.Accessed 17 Apr 2020.

15. Sin Y. All foreign workers in dorms to be tested for

Covid-19. The Straits Times. 13 May 2020. Coronavirus

pandemic. Available from: https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/all-foreign-workers-in-dorms-to-be-tested-for-covid-19. Accessed 13 May 2020.

16. Walensky RP, Del Rio C. From mitigation to containment

of the COVID-19 pandemic: putting the SARS-CoV-2

genie back in the bottle. JAMA 2020;323:1889-90. Crossref