Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

COMMENTARY

Cardiovascular risk in bus drivers

Chloe KY Cheung1, Sunny SL Tsang1, Oliver Ho1, Nathan Lam1, Edmund CL Lam1, Carolyn Ng1, Frances Sun1, Brian Yu1, Natalie Kwan1, Gilberto KK Leung1,2, MB, BS, PhD

1 Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

2 Department of Surgery, Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Prof Gilberto KK Leung (gilberto@hku.hk)

Introduction

Driver health is an important issue worldwide.

Cardiovascular risk is well known to be higher in bus

drivers than in the general population.1 2 3 4 5 Although

much media attention has been drawn towards the

recent increase in bus accidents in Hong Kong,6 7 8 few

studies or measures have been carried out. The aim

of this study was to examine available findings on

cardiovascular risks among bus drivers and related

policies on risk modification internationally and in

Hong Kong.

Cardiovascular risk in bus drivers

Previous studies have documented cardiovascular

risk in professional drivers. In Korea, a cross-sectional

study on 443 male bus drivers compared

their incidence of hypertension (53.3%) with two

control groups (17.6% and 19.7%, respectively). The

results showed that the odds ratio of developing

a cardiovascular event in bus drivers was 2.18

to 2.58.9 Another study was conducted through

questionnaires on a randomly selected cohort of

440 professional drivers in Sweden. It found a

1.13-times higher relative risk of developing

cardiovascular outcomes like stroke, and the odds

ratio of developing a cardiovascular event was 2.34.3

Before the implementation of the Labour Standards

Act, studies conducted on 2297 Taiwanese bus

drivers and skilled workers also showed higher

incidence of hypertension in bus drivers (72.4%,

986/1361) than skilled workers (30.6%, 164/536).2

The overall findings indicate that bus drivers of

different nationalities exhibit a higher cardiovascular

risk.

Risk factors in bus drivers

There are three main mechanisms predisposing

bus drivers to higher cardiovascular risk.9 An acute

episode due to a busy road with excessive traffic

and aggressive drivers, is the first major cause.

This is exacerbated by poor working conditions—a

combination of long working hours and insufficient

breaks in between shifts. These occupational factors

lead to obesity,10 high blood pressure,11 and poorly

controlled cholesterol levels.12 Finally, job stress

from being chronically overworked is also a contributing cause.13

Regulatory measures

Regulations aimed at reducing bus drivers’

cardiovascular risk are well established in Singapore,

Taiwan, and South Korea. In Singapore, all transport

operators must comply with the Employment Act,

which limits drivers’ working hours to 12 hours

per day (including overtime).14 The maximum

penalty for violation of regulations is SGD 5000

and a custodial sentence of 12 months.15 Under

Singapore’s ‘Healthier Workers, Happier Workers’

programme, free health talks and regular health

screening are provided at bus terminals during shift

changes.16 The Taiwanese Labour Standards Act

sets the maximum working hours of bus drivers

to 12 hours a day and uses digital tachograph for

monitoring.17 In South Korea, non-compliant bus

companies will be subjected to a fine or temporary

suspension of service.9 18 The installation of digital

tachographs to record information about driving

time and rest periods of drivers also effectively

monitors overwork.18

Workers’ compensation

Cardiovascular risk in bus drivers is one of the most

compensable conditions internationally,18 but it is not

recognised in Hong Kong. In Japan, workers can be

compensated for overwork-related health problems,

known colloquially as ‘karoshi’ (death by overwork).

Similarly, in Korea, the Ministry of Employment

and Labor outlined criteria for work-related

diseases liable for compensation to include cerebral

infarction, hypertensive encephalopathy, coronary

heart disease, and haemorrhagic stroke associated

with existing hypertension.18 In contrast, Hong Kong

bus drivers are rarely compensated, if at all, in this

regard. According to the Employees’ Compensation

Ordinance, the Labour Department would consider

whether there is a direct causal relationship between

the disease and certain type of work, taking into

account the availability of supportive scientific

evidence.19 Cardiovascular events do not fall under

the definition of occupational diseases as they can be

due to other factors that have no direct relationship

with work such as eating habits.

Situation in Hong Kong

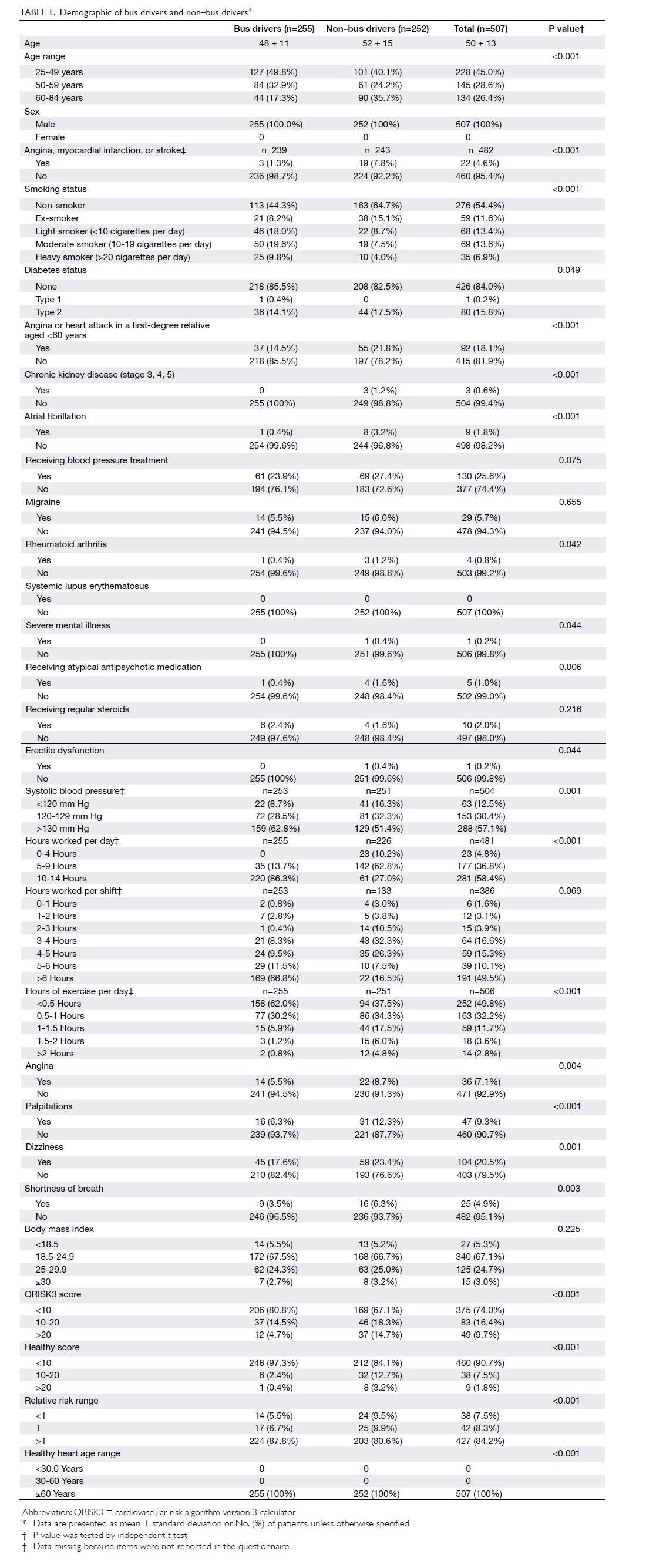

Recently, we conducted a questionnaire survey on

255 bus drivers and 252 non–bus drivers in Hong

Kong (Table 1). We included Chinese men aged 25

to 84 years; recruitment of bus drivers was done at

bus terminals and non–bus drivers were approached

at random outside the exits to train stations. The

QRISK3 (cardiovascular risk algorithm version 3

calculator) was used to assess cardiovascular risk by

quantifying the 10-year risk for myocardial infarction

and stroke in adults. Established cardiovascular risk

factors including hypertension, hyperlipidaemia,

diabetes, and smoking, and newly identified

cardiovascular risk factors were taken into account.20

Systolic blood pressure values were obtained either

by the drivers’ self-reporting, or by an automatic

sphygmomanometer on the spot. Other parameters

were based on subjects’ own recall.

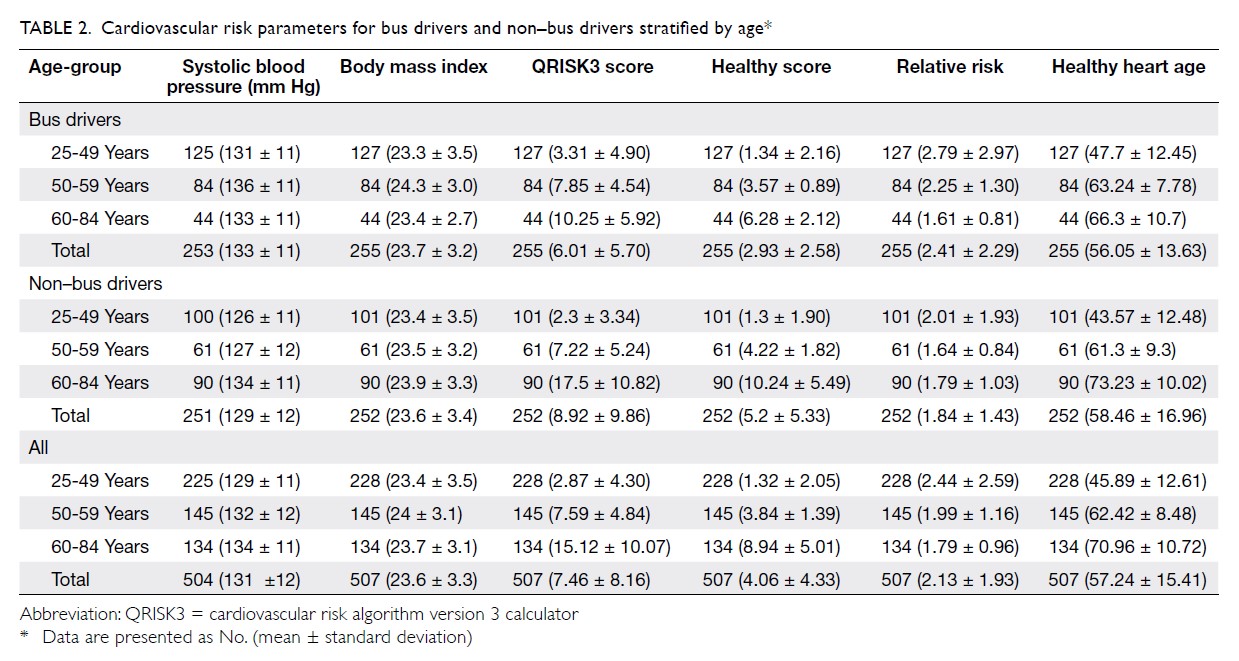

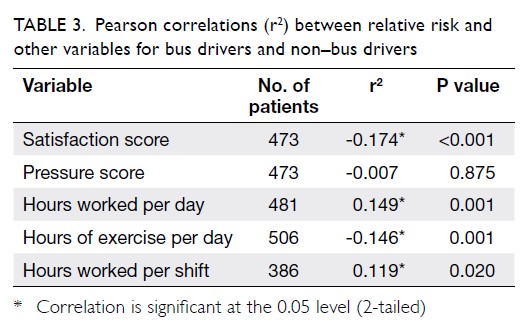

Our results (Table 2) showed that the relative

risk of developing cardiovascular diseases in bus

drivers (2.41) is higher than in non–bus drivers

(1.84) after age adjustment. This was attributable to

low exercise levels, poor job satisfaction, and long

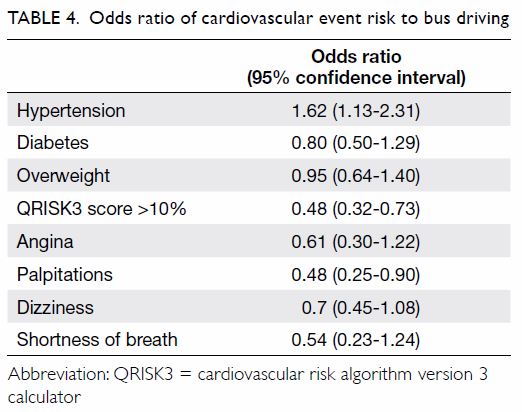

durations of working hours (Table 3). The odds of

developing hypertension (>140/90 mm Hg) in bus

drivers was 1.62-times higher than in non–bus

drivers (Table 4). Physical inactivity and smoking

were factors predisposing to hypertension. Only

7.9% of bus drivers did physical exercise for >1 hour

per day, and 47.4% were smokers, compared with

20.2% of non–bus drivers (Table 1). The sedentary

lifestyle of bus drivers in Hong Kong is consistent with previous studies that indicated bus drivers

spend 83% of their time at work sitting.21

Table 3. Pearson correlations (r2) between relative risk and other variables for bus drivers and non–bus drivers

Recommendations for Hong Kong

bus drivers

Bus driver health is crucial for ensuring the safety

of drivers, passengers, and other road-users.

According to the World Health Organization

recommendations, 30 minutes of aerobic exercise

3 times per week is ideal; short of that, there are

still added benefits in moving from the category of

“no activity” to “some levels” of activity.22 Smoking

cessation can be introduced in a stepwise fashion,

from counselling sessions, nicotine replacement

therapy, and varenicline use, to community

interventions introduced by the government.23

Educational programmes may be implemented

within communities of professional drivers in order

to improve the general health of bus drivers.

Currently, Hong Kong bus operators need to

adhere to the Transport Department’s Guidelines

regarding maximum duty hours (12 hours),

maximum driving hours (10 hours), and minimum

rest time (40 minutes after 6 hours of driving).19

However, bus operators are only issued warning

letters for non-compliance. Indeed, previous surveys

have shown that 51% of Hong Kong franchised

bus drivers worked ≥2 hours of overtime per day.24

Therefore, there is a need for the relevant authorities

to take action to safeguard bus drivers against

overwork and associated health hazards. To enhance

road safety, the feasibility of implementing regulatory measures or installation of digital tachographs to

monitor work hours and regular health screening

programmes should be explored in Hong Kong.

Conclusion

There is a higher relative risk of developing

cardiovascular diseases in bus drivers in Hong Kong

although most exhibit few cardiovascular symptoms

and belong to a younger age-group. The odds of

having hypertension were significantly higher in bus

drivers than in non–bus drivers. Stronger advocacy

for better lifestyle habits among bus drivers is

needed. Future studies should elucidate the causative

relationship between bus driving and cardiovascular

risk to complement existing policies on employee

compensation.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the concept of the study, acquisition

and analysis of the data, drafting of the manuscript, and

critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual

content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to

the study, approved the final version for publication, and take

responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

We thank all the survey participants, without whose support this commentary would not have been possible.

Funding/support

This commentary received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority Hong

Kong West Cluster (Ref UW 18-340). Informed consent from

subjects was obtained verbally.

References

1. Belkić K, Savić C., Theorell T, Rakić L, Ercegovac D,

Djordjević M. Mechanisms of cardiac risk among

professional drivers. Scand J Work Environ Health

1994;20:73-86. Crossref

2. Wang PD, Lin RS. Coronary heart disease risk factors in

urban bus drivers. Public Health 2001;115:261-4. Crossref

3. Hedberg GE, Jacobsson, KA, Janlert U, Langendoen S.

Risk indicators of ischemic heart disease among male

professional drivers in Sweden. Scand J Work Environ

Health 1993;19:326-33. Crossref

4. Tüchsen, F, Hannerz H, Roepstorff C, Krause N. Stroke

among male professional drivers in Denmark, 1994-2003.

Occup Environ Med 2006;63:456-60. Crossref

5. Bigert C, Gustavsson P, Hallqvist J, et al. Myocardial

infarction among professional drivers. Epidemiology

2003;14:333-9. Crossref

6. South China Morning Post. Hong Kong bus drivers plan

work-to-rule over Transport Department’s failure to

remove guidelines that can lead to 14-hour shifts. 2018.

Available from: http://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/community/article/2147157/hong-kong-bus-drivers-plan-work-rule-over-transport. Accessed 28 May 2018.

7. South China Morning Post. Hong Kong bus drivers’ working

hours in question after fatal crash. 2017. Available from:

http://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/community/article/2113275/hong-kong-bus-drivers-working-hours-question-after-fatal. Accessed 28 May 2018.

8. Chinadaily.com.cn. HK needs to mandate maximum

working hours. 2017. Available from: http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/hkedition/2017-09/26/content_32492186.htm. Accessed 28 May 2018.

9. Shin SY, Lee CG, Song HS, et al. Cardiovascular disease

risk of bus drivers in a city of Korea. Ann Occup Environ

Med 2013;25:34. Crossref

10. Rosso GL, Perotto M, Feola M, Bruno G, Caramella M.

Investigating obesity among professional drivers: the high

risk professional driver study. Am J Ind Med 2015;58:212-

9. Crossref

11. Lee JW, Lee NS, Lee KJ, Kim JJ. The association between

hypertension and lifestyle in express bus drivers. Korean J

Occup Environ Med 2011;23:270. Crossref

12. Catalina-Romero C, Calvo E, Sánchez-Chaparro MA, et al.

The relationship between job stress and dyslipidemia.

Scand J Public Health 2013;41:142-9. Crossref

13. Park J. Impact of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) on

work-relatedness evaluation in cerebrovascular and

cardiovascular diseases among workers. J Occup Health 2006;48:141-4. Crossref

14. Ministry of Manpower, Singapore Government. About

the Employment Act. Available from: https://www.mom.gov.sg/employment-practices/employment-act. 2012. Accessed 28 May 2018.

15. Ministry of Transport, Singapore Government. Written

reply by Minister for Transport Lui Tuck Yew to

parliamentary question on average working hours of public

transport drivers. 2012. Available from: https://www.mot.gov.sg/news-centre/news/Detail/Written%20reply%20by%20Minister%20for%20Transport%20Lui%20Tuck%20Yew%20to%20Parliamentary%20Question%20on%20Average%20Working%20Hours%20of%20Public%20Transport%20Drivers/. Accessed 28 May 2018.

16. Health Promotion Board, Singapore Government.

Tripartite Oversight Committee on Workplace Health:

2014-2017 Report. 2017. Available from: https://www.hpb.gov.sg/docs/default-source/default-document-library/tripartite-oversight-commitee-report_fa_hires.pdf?sfvrsn=7d34f672_0. Accessed 28 May 2018.

17. 台灣交通部《車輛安全檢測基準第十六點之一修正規

定》. Available from: https://law.moj.gov.tw/LawClass/LawAll.aspx?pcode=K0040003. Accessed 31 Jan 2018.

18. Kim DS, Kang SK. Work-related cerebro-cardiovascular

diseases in Korea. J Korean Med Sci 2010;25(Suppl):S105-11. Crossref

19. Hong Kong SAR Government. LCQ12: Occupational

safety and health of professional drivers [press release].

2018 Jan 17. Available from: https://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/201801/17/P2018011700708.htm. Accessed 28

May 2018.

20. Mueller PS. QRISK3 score estimates 10-year risk

for myocardial infarction and stroke. N Engl J Med

2017;357:j2099.

21. Varela-Mato V, Yates T, Stensel DJ, Biddle SJ, Clemes SA.

Time spent sitting during and outside working hours in bus

drivers: a pilot study. Prev Med Rep 2015;3:36-9. Crossref

22. World Health Organization. Physical activity and

adults. 2015. Available from https://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/factsheet_adults/en/. Accessed 28

May 2018.

23. World Health Organization. Quitting tobacco. 2011.

Available from https://www.who.int/tobacco/quitting/summary_data/en/. Accessed 28 May 2018.

24. Legislative Council, Hong Kong SAR Government.

Measures managing long working hours and occupational

fatigue of bus drivers. Available from https://www.legco.gov.hk/research-publications/english/essentials-1718ise07-measures-managing-long-working-hours-and-occupational-fatigue-of-bus-drivers.htm#endnote8.Accessed 28 May 2018.