Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

EDITORIAL

Prevention of postpartum haemorrhage

WC Leung, MD, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Kwong Wah Hospital, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr WC Leung (leungwc@ha.org.hk)

Postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) is an important

cause of maternal morbidity and mortality.

Prevention is always better than treatment. In this

issue of Hong Kong Medical Journal, Tse et al1 have

compared the use of carbetocin with oxytocin

infusion in reducing the need for additional

uterotonics or procedures in women at increased

risk for PPH undergoing Caesarean deliveries in

a single Hospital Authority (HA) obstetric unit.

Carbetocin was better than oxytocin infusion in

reducing the requirement of additional uterotonics

or procedures in pregnant women undergoing

Caesarean sections with multiple pregnancies or

major placenta praevia. The findings echo the first of

the three recommendations from the territory-wide

HA survey on massive PPH conducted in 2013.2 3

With the objectives of studying the

characteristics of patients with massive primary PPH

(defined as ≥1500 mL within the first 24 hours after

delivery, which is the clinical indicator for obstetric

performance in HA hospitals) and exploring areas for

improvement in terms of prevention and treatment,

a prospective study2 3 was conducted during the

year 2013 in all the eight HA obstetric units using

a pre-designed code sheet to record the details of

all patients with massive primary PPH, including

causes, risk factors, mode of delivery, interventions

(uterotonic agents, second-line therapies and

emergency hysterectomy), use of blood products,

and maternal outcome.

Massive primary PPH occurred in 0.76%

(n=277) of all deliveries (n=36 510) in HA obstetric

units in 2013. The incidence was comparable to those

reported in international literature. The majority

occurred after Caesarean sections (84.1%). Uterine

atony (37.5%), placenta praevia/accreta (49.9%),

and uterine wound bleeding/tear during Caesarean

section (24.2%) were the three most common causes.

The median total blood loss was 2000 mL (range,

1500-20 000 mL). Coagulopathy occurred in 16.2%

(n=45). A quarter (n=76, 27.4%) required intensive

care or high dependent unit admission. There was no

maternal mortality.

Second-line therapies (balloon tamponade,

compression sutures and uterine artery/internal

iliac artery embolisation or surgical ligation) were

used in 40.1% (n=111). Emergency hysterectomy

was required in 8.7% (n=24). A total of 1052 units of

packed cells, 670 units of platelets, 568 units of fresh frozen plasma, and 200 units of cryoprecipitate were

transfused.

The study identified three areas for

improvement: (1) to increase the choice of uterotonic

agents (carbetocin has been incorporated into HA

Drug Formulary since January 2017, mainly for

prevention of PPH in women at risk such as twin

pregnancy, large fibroids, polyhydramnios, fetal

macrosomia, and placenta praevia. In 2017, a total of

875 ampoules have been used in HA obstetric units,

rising to 2500 ampoules in 2018, and 2865 ampoules

in 2019); (2) to step up the use (and early use) of

second-line therapies, and to watch out for failures

from second-line therapy; (3) to reduce the incidence

of placenta praevia/accreta through education and

to improve its management at multiple care levels.

Carbetocin is a long-acting synthetic analogue

of oxytocin indicated for prevention of uterine

atony after Caesarean section. It is administered as

a slow intravenous injection over 1 minute, with a

rapid onset of uterine contraction within 2 minutes

and lasting for several hours. It is also a heat-stable

compound which does not require refrigeration.

Latest Cochrane reviews showed that carbetocin

may have some additional benefits compared with

oxytocin and appears to be without an increase in

adverse effects.4 The Carbetocin HAeMorrhage

PreventION (CHAMPION) trial5 showed that

carbetocin was non-inferior to oxytocin for the

prevention of PPH after vaginal delivery as well.

The main disadvantage of using carbetocin

in preventing PPH is its cost, making it much less

cost-effective when compared with other uterotonic

drugs.6 For local reference, carbetocin (single dose

of 100 μg) costs HK$200, as compared with oxytocin

(40 IU infusion, HK$32), syntometrine (single

dose, HK$27), and misoprostol (800 μg, HK$7).

As a result, when carbetocin was introduced into

HA Drug Formulary in 2017, we have limited its

use to those women with high-risk factors for PPH

after Caesarean sections such as twin pregnancy,

large fibroids, polyhydramnios, fetal macrosomia,

and placenta praevia. For example, in 2018, only

2500/35 016 or 7.1% of all deliveries in HA had

carbetocin for PPH prophylaxis when compared

with around 90% of deliveries in private hospitals

in Hong Kong. There is capacity to increase the use

of carbetocin in HA by including more women with

risk factors for PPH such as prolonged induction of labour (eg, oxytocin ≥12 hours), high parity (eg,

≥para 3), history of PPH, and others. These risk

factors have not been included in Tse et al’s study.1

Carbetocin should not only be considered for

Caesarean sections, but also for vaginal deliveries

with same risk factors for PPH. Furthermore, the

role of using carbetocin as treatment for PPH could

be explored.

In addition to single-centre studies on the

efficacy of a single drug or procedure on the

prevention and treatment of PPH, further studies are

required on the overall impact of the introduction

of uterotonic drugs such as carbetocin; non-uterotonic

drugs such as tranexamic acid; increasing

use of second-line procedures7 such as balloon

tamponade, compression sutures and uterine artery

embolisation; and new patient blood management

such as intravenous iron therapy, particularly in the

current era of inadequate blood donation, being

further aggravated by coronavirus disease 2019

(COVID-19).

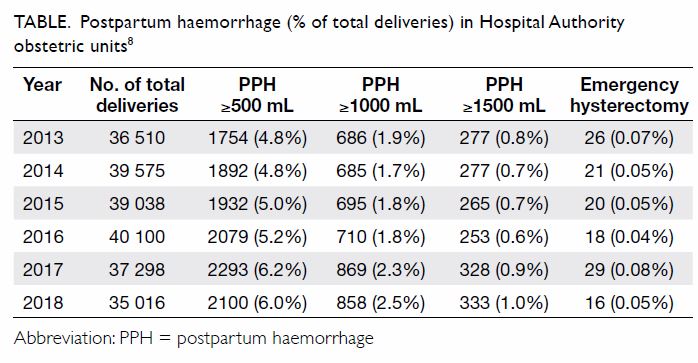

Interestingly, with all the new modalities of

prevention and treatment of PPH, the overall figures

of primary PPH ≥500 mL (traditional definition),

≥1000 mL or ≥1500 mL (defined as massive PPH),

including emergency hysterectomies for massive

PPH, have not been improved in HA from 2013

to 2018 (Table).8 This phenomenon is different

from what had been observed in a single obstetric

unit over a different time period from 2006 to

2011.9 Fortunately, maternal mortality is still rare.

Further studies are definitely indicated to look into

the territory-wide HA data (using the Obstetrics

Clinical Information System) to see whether the new

modalities are not as effective as they are expected

to be or our pregnant population is indeed becoming

more and more high risk for PPH.

Author contributions

The author contributed to the manuscript, approved the

final version for publication, and takes responsibility for its

accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

The author has disclosed no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Tse KY, Yu FN, Leung KY. Comparison of carbetocin and oxytocin infusions in reducing the requirement

for additional uterotonics or procedures in women at

increased risk for postpartum haemorrhage following

Caesarean section. Hong Kong Med J 2020;26:382-9. Crossref

2. Lau KW, Chan LL, Lo TK, Lau WL, Leung WC; Hospital

Authority COC Obstetrics and Gynaecology Quality

Assurance Subcommittee. Territory-wide massive primary

postpartum haemorrhage (PPH >1,500ml) survey in

Hospital Authority obstetric units with recommendations

and the way forward. Hospital Authority Convention 2017.

Master Class 7.1. Available from: http://www3.ha.org.hk/haconvention/hac2017/ebook/HAC2017_abstract%20day%201.pdf. Accessed 29 Sep 2020.

3. Leung WC. An overview on massive postpartum

haemorrhage in Hong Kong. The Hong Kong Medical

Diary 2019;24(7):2-3.

4. Gallos ID, Papadopoulou A, Man R, et al. Uterotonic agents

for preventing postpartum haemorrhage: a network meta-analysis.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018;(12):CD011689. Crossref

5. Widmer M, Piaggio G, Nguyen TM, et al. Heat-stable

carbetocin versus oxytocin to prevent hemorrhage after

vaginal birth. N Engl J Med 2018;379:743-52. Crossref

6. Pickering K, Gallos ID, Williams H, et al. Uterotonic drugs

for the prevention of postpartum haemorrhage: a cost-effectiveness

analysis. Pharmacoecon Open 2019;3:163-76. Crossref

7. Kellie FJ, Wandabwa JN, Mousa HA, Weeks AD.

Mechanical and surgical interventions for treating primary

postpartum haemorrhage. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

2020;(7):CD013663. Crossref

8. Hospital Authority Annual Obstetric Reports 2013 to 2018.

Available from: https://www.ekg.org.hk/html/gateway/neweKG/newsp/h1-obs-gyn.jsp (internal access via eKG).

9. Chan LL, Lo TK, Lau WL, et al. Use of second-line

therapies for management of massive primary postpartum

hemorrhage. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2013;122:238-43. Crossref