Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

EDITORIAL

Kidney health for everyone everywhere—from prevention to detection and equitable

access to care

Philip KT Li, MD, FRCP1 #; Guillermo Garcia-Garcia, MD2 #; SF Lui, MB, ChB, FRCP3 #; Sharon Andreoli, MD4 #; Winston WS Fung, MB BChir, MRCP1; Anne Hradsky, MA5; Latha Kumaraswami, BA6 #; Vassilios Liakopoulos, MD, PhD7 #; Ziyoda Rakhimova, BSc5; Gamal Saadi, MD8 #; Luisa Strani, ISN5 #; Ifeoma Ulasi, MB, BS, FWACP9 #; Kamyar Kalantar-Zadeh, MD, PhD10 #; for the World Kidney Day Steering Committee

1 Department of Medicine and Therapeutics, Carol and Richard Yu Peritoneal Dialysis Research Centre, Prince of Wales Hospital, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

2 Nephrology Service, Hospital Civil de Guadalajara Fray Antonio Alcalde, University of Guadalajara Health Sciences Center, Guadalajara, Mexico

3 Division of Health System, Policy and Management, Jockey Club School of Public Health and Primary Care, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

4 James Whitcomb Riley Hospital for Children, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, United States

5 World Kidney Day Office, Brussels, Belgium

6 TANKER Foundation, Chennai, India

7 Division of Nephrology and Hypertension, First Department of Internal Medicine, AHEPA Hospital, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece

8 Nephrology Unit, Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Cairo University, Giza, Egypt

9 Renal Unit, Department of Medicine, College of Medicine, University of Nigeria, Ituku-Ozalla, Enugu, Nigeria

10 Division of Nephrology and Hypertension and Kidney Transplantation, University of California Irvine School of Medicine, Orange, California, United States

# Members of the World Kidney Day Steering Committee

Corresponding authors: Dr Philip KT Li; Dr Kamyar Kalantar-Zadeh (philipli@cuhk.edu.hk; kkz@uci.edu)

Introduction

Around 850 million people are currently affected

by different types of kidney disorders.1 Up to one

in 10 adults worldwide has chronic kidney disease

(CKD), which is invariably irreversible and mostly

progressive. The global burden of CKD is increasing,

and CKD is projected to become the fifth most

common cause of years of life lost globally by 2040.2

If CKD remains uncontrolled and if the affected

person survives the ravages of cardiovascular and

other complications of the disease, CKD progresses

to end-stage renal disease (ESRD), where life cannot

be sustained without dialysis therapy or kidney

transplantation. Hence, CKD is a major cause of

catastrophic health expenditure.3 The costs of

dialysis and transplantation consume 2% to 3% of the

annual healthcare budget in high-income countries,

and spent on <0.03% of the total population of these

countries.4

Importantly, however, kidney disease can be

prevented and progression to ESRD can be delayed

with appropriate access to basic diagnostics and

early treatment including lifestyle modifications and

nutritional interventions.4 5 6 7 8 Despite this, access to

effective and sustainable kidney care remains highly

inequitable across the world, and kidney disease a low health priority in many countries. Kidney disease is crucially missing from the international

agenda for global health. Notably absent from the

impact indicators for the Sustainable Development

Goal Goal 3. Target 3.4: “By 2030, reduce by one

third premature mortality from non-communicable

diseases (NCDs) through prevention and treatment

and promote mental health and well-being” and from

the latest iteration of the United Nations Political

Declaration on NCDs, kidney diseases urgently

need to be given political attention, priority, and

consideration.9 Current global political commitments

on NCDs focus largely on four main diseases:

cardiovascular disease (CVD), cancer, diabetes, and

chronic respiratory diseases. Yet, it is estimated

that 55% of the global NCD burden is attributed to

diseases outside of this group.10 Furthermore, kidney

disease frequently co-exists with one or more of the

above four major NCDs, leading to worse health

outcomes. Chronic kidney disease is a major risk

factor for heart disease and cardiac death, as well

as for infections such as tuberculosis, and is a major

complication of other preventable and treatable

conditions including diabetes, hypertension, human

immunodeficiency virus, and hepatitis.4 5 6 7 As the

Sustainable Development Goals and Universal Health Coverage agendas progress and provide a platform for raising awareness of NCD healthcare

and monitoring needs, targeted action on kidney

disease prevention should become integral to the

global policy response.1 The global kidney health

community calls for the recognition of kidney disease

and effective identification and management of its

risk factors as a key contributor to the global NCD

burden and the implementation of an integrated and

people-centred approach to care.

Definition and classification of

chronic kidney disease prevention

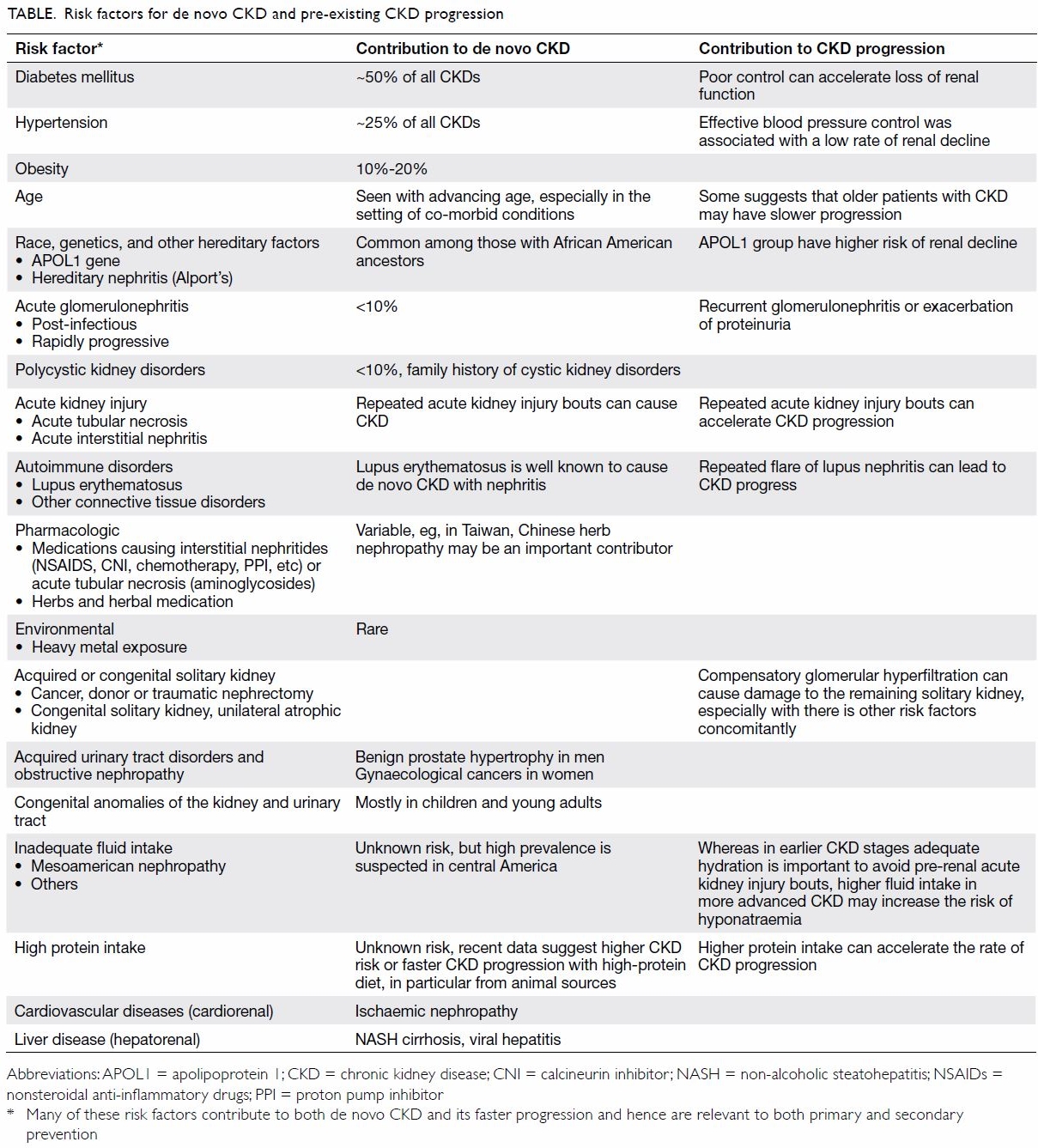

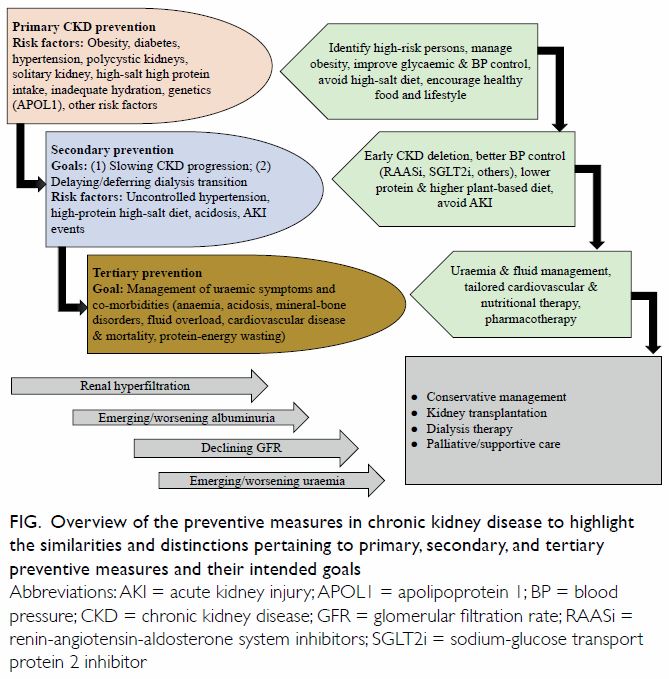

According to the expert definitions including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,11

the term “prevention” refers to activities that

are typically categorised by the following three

definitions: (1) primary prevention, which implies

intervening before health effects occur in an effort

to prevent the onset of illness or injury before the

disease process begins; (2) secondary prevention,

which suggests preventive measures that lead to

early diagnosis and prompt treatment of a disease

to prevent more severe problems developing and

includes screening to identify diseases in the earliest

stages; and (3) tertiary prevention, which indicates

managing disease after it is well established in order

to control disease progression and the emergence of

more severe complications, which is often by means of targeted measures such as pharmacotherapy, rehabilitation, and screening for and management of

complications. These definitions have an important

bearing on the prevention and management of the

CKD, and accurate identification of risk factors that

cause CKD or lead to faster progression to renal

failure as shown in the Figure are relevant in health

policy decisions and health education and awareness

related to CKD.12

Figure. Overview of the preventive measures in chronic kidney disease to highlight the similarities and distinctions pertaining to primary, secondary, and tertiary preventive measures and their intended goals

Primary prevention of chronic kidney disease

The incidence and prevalence of CKD have been

rising worldwide.13 This primary level of prevention

requires awareness of modifiable CKD risk factors

and efforts to focus healthcare resources on those

patients who are at the highest risk of developing

new onset or de novo CKD.

Measures to achieve effective primary

prevention should focus on the two leading risk

factors for CKD including diabetes mellitus and

hypertension. Evidence suggests that an initial

mechanism of injury is renal hyperfiltration with

seemingly elevated glomerular filtration rate

(GFR), above normal ranges. This is often the

result of glomerular hypertension that is often

seen in patients with obesity or diabetes mellitus,

but it can also occur after high dietary protein

intake.8 Other CKD risk factors include polycystic

kidneys or other congenital or acquired structural

anomalies of the kidney and urinary tracts, primary

glomerulonephritis, exposure to nephrotoxic

substances or medications (such as nonsteroidal

anti-inflammatory drugs), having one single kidney,

eg, solitary kidney after cancer nephrectomy, high

dietary salt intake, inadequate hydration with

recurrent volume depletion, heat stress, exposure to

pesticides and heavy metals (as has been speculated

as the main cause of Mesoamerican nephropathy),

and possibly high protein intake in those at higher

risk of CKD.8 Among non-modifiable risk factors

are advancing age and genetic factors such as

apolipoprotein 1 gene that is mostly encountered in

those with sub-Saharan African ethnicity, especially

among African Americans. Certain disease states

may cause de novo CKD such as cardiovascular

and atheroembolic diseases (also known as

secondary cardiorenal syndrome) and liver diseases

(hepatorenal syndrome). Some of the risk factors of

CKD are shown in the Table.

Among measures to prevent the emergence

of de novo CKD are screening efforts to identify

and treat patients at high risk of CKD, especially

those with diabetes mellitus and hypertension.

Hence, targeting primordial risk factors of these

two conditions including metabolic syndrome and

overnutrition is relevant to primary CKD prevention

as is correcting obesity.14 Promoting healthier

lifestyle is an important means to that end including physical activity and healthier diet. The latter should

be based on more plant-based foods with less meat,

less sodium intake, more complex carbohydrates

with higher fibre intake, and less saturated fat. In

those with hypertension and diabetes, optimising

blood pressure and glycaemic control has shown to be effective in preventing diabetic and hypertensive nephropathies. A recent expert panel suggested

that patients with solitary kidney should avoid high

protein intake >1 g/kg body weight per day.15 Obesity

should be avoided, and weight reduction strategies

should be considered.14

Secondary prevention in chronic kidney

disease

Evidence suggests that among patients with CKD,

the vast majority have an early stage of the disease, ie,

CKD stages 1 and 2 with microalbuminuria (30-300

mg/day) or CKD stage 3B (ie, estimated GFR between

45 and 60 mL/min/1.73 m2).16 In these patients with

pre-existing disease, the secondary prevention of

CKD has the highest priority. For these earlier stages

of CKD, the main goal of kidney health education

and clinical interventions is how to slow disease

progression. Uncontrolled or poorly controlled

hypertension is one of the most established risk

factors for faster CKD progression. The underlying

pathophysiology of faster CKD progression relates

to ongoing damage to the kidney structure and loss

of nephrons with worsening interstitial fibrosis as

it happens with sustained hypertension. A target

of blood pressure of <130/80 mmHg should be

recommended.

The cornerstone of the pharmacotherapy

in secondary prevention is the use of angiotensin

pathway modulators, also known as renin-angiotensin-

aldosterone system inhibitors. These

drugs reduce both systemic blood pressure and

intraglomerular pressure by opening efferent

arterioles of the glomeruli, hence, leading to

longevity of the remaining nephrons. Low-protein

diet appears to have a synergistic effect on renin-angiotensin-

aldosterone system inhibitor therapy.17

In terms of the potential effect of controlling

glycaemic status and correcting obesity on the

rate of CKD progression, there are mixed data.

However, recent data suggest that a new class

of antidiabetic medications known as sodium-glucose

cotransporter-2 inhibitors can slow CKD

progression, but this effect may not be related

to glycaemic modulation of the medication. The

CREDENCE study demonstrated that the risk of

renal failure is significantly lower in the canagliflozin

group than the placebo group.18 Another emerging

antidiabetic agent in delaying kidney injury is

the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist.19 A

glycated haemoglobin level of <7% should be the

goal. Whereas acute kidney injury (AKI) may or

may not cause de novo CKD, AKI events that are

superimposed on pre-existing CKD may accelerate

disease progression.20 In particular, judicious use of

nephrotoxic agents (such as iodine-based contrast,

chemotherapeutic agents and immunomodulatory

drugs) in patients with pre-existing CKD is

imperative in order to prevent new AKI. A relatively

recent case of successful secondary prevention

that highlights the significance of implementing

preventive strategies in CKD is the use of a

vasopressin V2-receptor antagonists in autosomal

dominant polycystic kidney disease.21

Tertiary prevention in chronic kidney disease

In patients with advanced CKD, management of

uraemia and related co-morbid conditions such as

anaemia, mineral and bone disorders, and CVD is

of high priority, so that these patients can continue

to achieve the highest longevity. These measures can

be collectively referred to as tertiary prevention of

CKD. In these patients, CVD burden is exceptionally

high, especially if they have underlying diabetes

or hypertension, while they often do not follow

other traditional profile of cardiovascular risk such

as obesity or hyperlipidaemia. Indeed, in these

patients, a so-called reverse epidemiology exists,

in which hyperlipidaemia and obesity appear to be

protective at this advanced stage of CKD. This could

be due to the overshadowing impact of the protein-energy

wasting that happens more frequently with

worsening uraemia and which is associated with

weight loss and poor outcomes including CVD and

death. Whereas many of these patients, if they survive

ravages of protein-energy wasting and CVD, will

eventually receive renal replacement therapy in form

of dialysis therapy or kidney transplantation, a new

trend is emerging to maintain them longer without

dialysis by implementing conservative management

of CKD. However, in some with additional co-morbidities

such as metastatic cancers, palliative

measures with supportive care can be considered.

Identification of chronic kidney

disease

The lack of awareness of CKD around the world

is one of the reasons for late presentation of CKD

in both developed and developing economies.22 23 24

The overall CKD awareness among the general

population and even high cardiovascular risk groups

across 12 low-income and middle-income countries

(LMIC) was <10%.24

Given its asymptomatic nature, screening

of CKD plays an important role in early detection.

Consensus and positional statements have

been published by the International Society of

Nephrology,25 National Kidney Foundation,26

Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes,27

NICE Guidelines,28 and Asian Forum for Chronic

Kidney Disease Initiatives.29 There was lack of trials

to evaluate screening and monitoring of CKD.30

Currently, most will promote a targeted screening

approach to early detection of CKD. Some of the

major groups at risk for targeted screening include

patients with diabetes; hypertension; patients with

a family history of CKD; patients taking potentially

nephrotoxic drugs, herbs, substances, or indigenous

medicines; patients with a history of AKI; and

patients aged >65 years.29 31 Chronic kidney disease

can be detected with two simple tests: a urine test for the detection of proteinuria and a blood test to

estimate the GFR.26 29

Given that currently a population screening

for CKD is not recommended and it was claimed

that it might add unintended harm to the general

population being screened,30 there is no speciality

society or preventive services group which

recommends general screening.32 Low-to-middle-income

countries are ill-equipped to deal with the

devastating consequences of CKD, particularly the

late stages of the disease. There are suggestions

that screening should primarily include high-risk

patients, but also extend to those with suboptimal

levels of risk, eg, pre-diabetes and prehypertension.33

Cost-effectiveness of early

detection programmes

Universal screening of the general population

would be time-consuming, expensive, and has been

shown to be not cost-effective. Unless selectively

directed towards high-risk groups, such as the

case of unknown cause of CKD in disadvantaged

populations,34 according to a cost-effectiveness

analysis using a Markov decision analytic model,

population-based dipstick screening for proteinuria

has an unfavourable cost-effectiveness ratio.35 A

more recent Korean study confirmed that their

National Health Screening Program for CKD is

more cost-effective for patients with diabetes or

hypertension than the general population.36 From an

economic perspective, screening CKD by detection

of proteinuria was shown to be cost-effective in

patients with hypertension or diabetes in a systematic

review.37 The incidence of CKD, rate of progression,

and effectiveness of drug therapy were major drivers

of cost-effectiveness and thus CKD screening may

be more cost-effective in populations with higher

incidences of CKD, rapid rates of progression, and

more effective drug therapy.

Rational approach to chronic

kidney disease early detection

The approach towards CKD early detection will

include the decision for frequency of screening,

who should perform the screening and intervention

after screening.23 Screening frequency for targeted

patients should be yearly if no abnormality is

detected on initial evaluation. This is in line with

the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes

resolution that the frequency of testing should

be according to the target group to be tested and

generally needs not be more frequent than once

per year.27 Who should perform the screening is

always a question especially when the healthcare

professional availability is a challenge in lower-income

economies. Physicians, nurses, paramedical staff, and other trained healthcare professionals are eligible to do the screening tests. Intervention after screening is also important and patients detected to

have CKD should be referred to primary care and

general physicians with experience in management

of kidney disease for follow-up. A management

protocol should be provided to primary care and

general physicians. Further referral to nephrologists

for management will be based on the well-defined

protocols.24 27 29

Integration of chronic kidney

disease prevention into national non-communicable disease programmes

Given the close links between CKD and other

NCDs, it is critical that CKD advocacy efforts be

aligned with existing initiatives concerning diabetes,

hypertension, and CVD, particularly in LMIC. Some

countries and regions have successfully introduced

CKD prevention strategies as part of their NCD

programmes. As an example, in 2003, a kidney

health promotion programme was introduced in

Taiwan, with its key components including a ban on

herbs containing aristolochic acid, public awareness

campaigns, patient education, funding for CKD

research, and the setting up of teams to provide

integrated care.38 In Cuba, the Ministry of Public

Health has implemented a national programme for

the prevention of CKD. Since 1996 the programme

has followed several steps: (1) analysis of the

resources and health situation in the country; (2)

epidemiological research to define the burden of

CKD; and (3) continuing education for nephrologists,

family doctors, and other health professionals. The

main goal has been to bring nephrology care closer

to the community through a regional redistribution

of nephrology services and joint treatment of

patients with CKD by primary healthcare physicians

and nephrologists.39 The integration of CKD

prevention into NCD programme has resulted in

the reduction of renal and cardiovascular risks in the

general population. Main outcomes have been the

reduction in the prevalence of risk factors, such as

low birth weight, smoking, and infectious diseases.

There has been an increased rate of the diagnosis

of diabetes and of glycaemic control, as well as an

increased diagnosis of patients with hypertension,

higher prescription use of renoprotective treatment

with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, and

higher rates of blood pressure control.40 Recently,

the United States Department of Health and Human

Services has introduced an ambitious programme to

reduce the number of Americans developing ESRD

by 25% by 2030. The programme, known as the

Advancing American Kidney Health initiative, has set goals with metrics to measure its success; among

them is to put more efforts to prevent, detect, and

slow the progression of kidney disease, in part by

addressing traditional risk factors such as diabetes

and hypertension. To reduce the risk of kidney

failure, the programme contemplates advancing

public health surveillance and research to identify

populations at risk and those in early stages of kidney

disease, and to encourage adoption of evidence-based

interventions to delay or stop progression to

kidney failure.41 Ongoing programmes, such as the

Special Diabetes Program for Indians, represent

an important part of this approach by providing

team-based care and care management. After

implementation of that programme, the incidence

of diabetes-related kidney failure among Indian

populations decreased by over 40% between 2000

and 2015.42

Involvement of primary care

physicians and other health professionals

Detection and prevention of CKD programmes

require considerable resources both in terms

of manpower and funds. Availability of such

resources will depend primarily on the leadership

of nephrologists.43 However, the number of

nephrologists is not sufficient to provide renal

care to the growing number of patients with CKD

worldwide. It has been suggested that most cases

of non-progressive CKD can be managed without

referral to a nephrologist, and specialist referral

can be reserved for patients with an estimated

GFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2, rapidly declining kidney

function, persistent proteinuria, or uncontrolled

hypertension or diabetes.44 It has been demonstrated

that with an educational intervention the clinical

competence of family physicians increases, resulting

in preserved renal function in diabetic patients with

early renal disease.45 The practitioners who received

the educational intervention used significantly

more angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors,

angiotensin-receptor blockers, and statins than did

practitioners who did not receive it. The results

were similar to those found in patients treated by

nephrologists.46 The role of primary healthcare

professionals in the implementation of CKD

prevention strategies in LMIC has been recently

illustrated.47

The e-Learning has become an increasingly

popular approach to medical education. Online

learning programmes for NCD prevention and

treatment, including CKD, have been successfully

implemented in Mexico. By 2015, over 5000 health

professionals (including non-nephrologists) had

been trained using an electronic health education

platform.48

Shortage of nephrology

manpower—implications for prevention

The resources for nephrology care remain at critical levels in many parts of the world. Even in Western

developed countries, nephrologists are frequently in

short supply. In a selection of European countries with

similar, predominantly public, healthcare systems,

there was a substantial variation in the nephrology

workforce. Countries such as Italy, Greece, and Spain

reported the highest ratios, whereas countries such

as Ireland, Turkey, and the United Kingdom had the

lowest ratios.49 In the United States, the number of

nephrologists per 1000 ESRD patients has declined

from 18 in 1997 to 14 in 2010.50 The situation in the

developing world is even worse. With the exception

of Nigeria, Sudan, Kenya and South Africa, in many

countries of sub-Saharan Africa there are <10

nephrologists. The number of nephrology nurses

and dialysis technicians is also insufficient.51 In Latin

America the average number of nephrologists is

13.4 per million population (pmp). However, there

is unequal distribution between countries; those

with <10 nephrologists pmp (Honduras, 2.1 pmp;

Guatemala, 3.3 pmp; and Nicaragua, 4.6 pmp), and

those >25 pmp (Cuba, 45.2 pmp; Uruguay, 44.2 pmp;

and Argentina, 26.8 pmp).52

The causes of this shortage are multiple.

Potential contributors to this variation include the

increasing burden of CKD, erosion of nephrology

practice scope by other specialists, lack of workforce

planning in some countries relative to others, and

the development of new care delivery models.50 A

novel strategy has been the successful International

Society of Nephrology’s Fellowship programme.

Since its implementation in 1985, over 600 fellows

from >83 LMIC have been trained. A significant

number of fellowships were undertaken in selected

developed centres within the fellow’s own region. In

a recent survey, 85% of responding fellows were re-employed

by their home institutions.53 54

Interdisciplinary prevention

approach

Since 1994, a National Institute of Health consensus

advocated for early medical intervention in

predialysis patients. Owing to the complexity of care

of CKD, it was recommended that patients should

be referred to a multidisciplinary team consisting

of nephrologist, dietitian, nurse, social worker, and

health psychologist, with the aim to reduce predialysis

and dialysis morbidity and mortality.55 In Mexico,

a nurse-led protocol-driven multidisciplinary

programme reported better preservation in estimated

GFR and a trend in the improvement of quality of

care of patients with CKD similar to those reported by other multidisciplinary clinic programmes in

the developed world. Additionally, more patients

started dialysis non-emergently, and some obtained

a pre-emptive kidney transplant. For those unable

to obtain dialysis or who choose not to, a palliative

care programme is now being implemented.56 Care

models supporting primary care providers or allied

health workers achieved better effectiveness in

slowing kidney function decline when compared to

those providing speciality care. Future models should

address region-specific causes of CKD, increase the

quality of diagnostic capabilities, establish referral

pathways, and provide better assessments of clinical

effectiveness and cost-effectiveness.57

Online educational programmes

for chronic kidney disease

prevention and treatment

Whereas it is important to enhance the promotion

and implementation of prevention of kidney disease

and kidney failure among healthcare professionals,

it is equally important to promote prevention with

education programmes for those at risk of kidney

disease and kidney failure, and with the general

population at large. It is a stepwise process, from

awareness, through engagement, participation,

and empowerment, to partnership. As highlighted

above, in general, the health literacy of the general

population is low. Awareness and understanding of

kidney disease are inadequate. Education is key to

engaging patients with kidney disease. It is the path to

self-management and patient-centred care. Narva et

al58 found patient education is associated with better

patient outcomes. Obstacles include the complex

nature of kidney disease information, low baseline

awareness, limited health literacy and numeracy,

limited availability of CKD information, and lack

of readiness to learn. New education approaches

should be developed through research and quality

improvement efforts. Schatell59 found that web-based

kidney education is helpful in supporting patient self-management. The internet offers a

wealth of resources on education. Understanding

the types of internet sources that patients with

CKD use today can help renal professionals to point

patients in the right direction. It is important that

reputable healthcare organisations, preferably at a

national level, facilitate users to have easier access

to health information on their websites (as shown

in online supplementary Appendix). The mode of

communication currently used by patients and the

population at large is through the internet—websites,

portals, and other social media, such as Facebook and

Twitter. There are also free apps on popular mobile

devices providing education on kidney disease.

There is no shortage of information on the internet. The challenge is how to effectively push important

healthcare information in a targeted manner, and to

facilitate users seeking information in their efforts

to pull relevant and reliable information from the

internet. It is important that health information is

relevant for the condition (primary, secondary or

tertiary prevention), and offered at the right time

to the right recipient. It is possible, with the use of

information technology and informatics, to provide

relevant and targeted information for patients at high

risk, coupling the information based on diagnosis

and drugs prescribed. Engagement of professional

society resources and patient groups is a crucial

step to promote community partnership and patient

empowerment on prevention. Additional resources

may be available from charitable and philanthropic

organisations.

Renewed focus on prevention,

awareness-raising, and education

Given the urgency for increased education and

awareness on the importance of the preventive

measures, we suggest the following goals to redirect

the focus on plans and actions:

1. Empowerment through health literacy in order

to develop and support national campaigns that

bring public awareness to prevention of kidney

disease.

2. Population-based approaches to manage key known risks for kidney disease such as blood pressure control, and effective management of obesity and diabetes.

3. Implementation of the World Health Organization ‘Best Buys’ approach including screening of at-risk populations for CKD, universal access to essential diagnostics of early CKD, availability of affordable basic technologies and essential medicines and task shifting from doctors to frontline healthcare workers to more effectively target the progression of CKD and other secondary preventative approaches.

2. Population-based approaches to manage key known risks for kidney disease such as blood pressure control, and effective management of obesity and diabetes.

3. Implementation of the World Health Organization ‘Best Buys’ approach including screening of at-risk populations for CKD, universal access to essential diagnostics of early CKD, availability of affordable basic technologies and essential medicines and task shifting from doctors to frontline healthcare workers to more effectively target the progression of CKD and other secondary preventative approaches.

To that end, the motto “Kidney Health for

Everyone, Everywhere” is more than a tagline or

wishful thinking. It is a policy imperative which

can be successfully achieved if policy-makers,

nephrologists, and healthcare professionals place

prevention and primary care for kidney disease

within the context of their Universal Health Coverage

programmes.

Author contributions

PKT Li and K Kalantar-Zadeh serve as the corresponding authors. All the authors contributed equally otherwise.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the

study, approved the final version for publication, and take

responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This editorial received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration

This article was originally published in Kidney International, volume 97, pages 226-232, Copyright World Kidney Day

Steering Committee (2020), and reprinted concurrently in

several journals. The articles cover identical concepts and

wording but vary in minor stylistic and spelling changes,

detail, and length of manuscript in keeping with each journal’s

style. Any of these versions may be used in citing this article.

References

1. International Society of Nephrology. 2019 United Nations

high level meeting on universal health coverage: moving

together to build kidney health worldwide. Available from:

https://www.theisn.org/images/Advocacy_4_pager_2019_

Final_WEB_pagebypage.pdf. Accessed 20 Jul 2019.

2. Foreman KJ, Marquez N, Dolgert A, et al. Forecasting life expectancy, years of life lost, and all-cause and cause-specific

mortality for 250 causes of death: reference and alternative

scenarios for 2016-40 for 195 countries and territories. Lancet

2018;392:2052-90. Crossref

3. Essue BM, Laba TL, Knaul F, et al. Economic burden of

chronic ill health and injuries for households in low- and

middle-income countries. In: Jamison DT, Gelband H, Horton

S, et al, editors. Disease Control Priorities Improving Health

and Reducing Poverty, 3rd ed. Washington, DC: World Bank;

2018: 121-43. Crossref

4. Vanholder R, Annemans L, Brown E, et al. Reducing the costs

of chronic kidney disease while delivering quality health care:

a call to action. Nat Rev Nephrol 2017;13:393-409. Crossref

5. Luyckx VA, Tuttle KR, Garcia-Garcia G, et al. Reducing major

risk factors for chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl

(2011) 2017;7:71-87. Crossref

6. Luyckx VA, Tonelli M, Stanifer JW. The global burden of

kidney disease and the sustainable development goals. Bull

World Health Organ 2018;96:414-22D. Crossref

7. Tonelli M, Muntner P, Lloyd A, et al. Risk of coronary events

in people with chronic kidney disease compared with those

with diabetes: a population-level cohort study. Lancet

2012;380:807-14. Crossref

8. Kalantar-Zadeh K, Fouque D. Nutritional management of

chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 2017;377:1765-76. Crossref

9. United Nations General Assembly. Political declaration of

the third high-level meeting of the General Assembly on

the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases.

Available from: https://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.

asp?symbol=A/73/L.2&Lang=E. Accessed 19 Nov 2019.

10. Lopez AD, Williams TN, Levin A, et al. Remembering

the forgotten non-communicable diseases. BMC Med

2014;12:200.Crossref

11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. At-a-glance:

Executive Summary, Picture of America. Available from:

https://www.cdc.gov/pictureofamerica. Accessed 19 Nov

2019.

12. Levey AS, Schoolwerth AC, Burrows NR, Williams DE,

Stith KR, McClellan W; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Expert Panel. Comprehensive public health

strategies for preventing the development, progression, and

complications of CKD: report of an expert panel convened by

the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Am J Kidney

Dis 2009;53:522-35. Crossref

13. Saran R, Robinson B, Abbott KC, et al. US Renal Data System

2018 Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in

the United States. Am J Kidney Dis 2019;73(3S1):A7-A8. Crossref

14. Kovesdy CP, Furth SL, Zoccali C, World Kidney Day Steering

Committee. Obesity and kidney disease: hidden consequences

of the epidemic. J Ren Nutr 2017;27:75-7. Crossref

15. Tantisattamo E, Dafoe DC, Reddy UG, et al. Current

management of patients with acquired solitary kidney. Kidney

Int Rep 2019;4:1205-18. Crossref

16. Webster AC, Nagler EV, Morton RL, Masson P. Chronic

kidney disease. Lancet 2017;389:1238-52. Crossref

17. Koppe L, Fouque D. The role for protein restriction in

addition to renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors

in the management of CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 2019;73:248-57. Crossref

18. Perkovic V, Jardine MJ, Neal B, et al. Canagliflozin and renal

outcomes in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med

2019;380:2295-306. Crossref

19. Greco EV, Russo G, Giandalia A, Viazzi F, Pontremoli R, De

Cosmo S. GLP-1 receptor agonists and kidney protection.

Medicina (Kaunas) 2019;55(6).pii: E233. Crossref

20. Rifkin DE, Coca SG, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Does AKI truly lead

to CKD? J Am Soc Nephrol 2012;23:979-84. Crossref

21. Torres VE, Chapman AB, Devuyst O, et al. Tolvaptan in

patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease.

N Engl J Med 2012;367:2407-18. Crossref

22. Verhave JC, Troyanov S, Mongeau F, et al. Prevalence,

awareness, and management of CKD and cardiovascular risk

factors in publicly funded health care. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol

2014;9:713-9. Crossref

23. Chow KM, Szeto CC, Kwan B, Leung CB, Li PK. Public lacks

knowledge on chronic kidney disease: telephone survey.

Hong Kong Med J 2014;20:139-44. Crossref

24. Ene-Iordache B, Perico N, Bikbov B, et al. Chronic kidney

disease and cardiovascular risk in six regions of the world

(ISN-KDDC): a cross-sectional study. Lancet Glob Health

2016;4:e307-19. Crossref

25. Li PK, Weening JJ, Dirks J, et al. A report with consensus

statements of the International Society of Nephrology 2004

Consensus Workshop on Prevention of Progression of

Renal Disease, Hong Kong, June 29, 2004. Kidney Int Suppl

2005;(94):S2-7. Crossref

26. Vassalotti JA, Stevens LA, Levey AS. Testing for chronic

kidney disease: A position statement from the National

Kidney Foundation. Am J Kidney Dis 2007;50:169-80. Crossref

27. Levey AS, Atkins R, Coresh J, et al. Chronic kidney disease as

a global public health problem: Approaches and initiatives—a

position statement from Kidney Disease Improving Global

Outcomes. Kidney Int 2007;72:247-59. Crossref

28. Crowe E, Halpin D, Stevens P; Guideline Development Group.

Early identification and management of chronic kidney

disease: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ 2008;337:a1530. Crossref

29. Li PK, Chow KM, Matsuo S, et al. Asian chronic kidney

disease best practice recommendations: positional statements

for early detection of chronic kidney disease from Asian

Forum for Chronic Kidney Disease Initiatives (AFCKDI).

Nephrology (Carlton) 2011;16:633-41. Crossref

30. Fink HA, Ishani A, Taylor BC, et al. Screening for, monitoring, and treatment of chronic kidney disease stages 1 to 3: A

systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force

and for an American College of Physicians Clinical Practice

Guideline. Ann Intern Med 2012;156:570-81.Crossref

31. Li PK, Ng JK, Cheng YL, et al. Relatives in silent kidney disease

screening (RISKS) study: a Chinese cohort study. Nephrology

(Carlton) 2017;22 Suppl 4:35-42. Crossref

32. Samal L, Linder JA. The primary care perspective on routine

urine dipstick screening to identify patients with albuminuria.

Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2013;8:131-5.Crossref

33. George C, Mogueo A, Okpechi I, Echouffo-Tcheugui JB,

Kengne AP. Chronic kidney disease in low-income to middle-income

countries: the case for increased screening. BMJ Glob

Health 2017;2:e000256. Crossref

34. Gonzalez-Quiroz M, Nitsch D, Hamilton S, et al. Rationale

and population-based prospective cohort protocol for the

disadvantaged populations at risk of decline in eGFR (CO-DEGREE).

BMJ Open 2019;9:e031169. Crossref

35. Boulware LE, Jaar BG, Tarver-Carr ME, Brancati FL, Powe NR. Screening for proteinuria in US adults: A cost-effectiveness

analysis. JAMA 2003;290:3101-14. Crossref

36. Go DS, Kim SH, Park J, Ryu DR, Lee HJ, Jo MW. Cost-utility

analysis of the National Health Screening Program for chronic

kidney disease in Korea. Nephrology (Carlton) 2019;24:56-64. Crossref

37. Komenda P, Ferguson TW, Macdonald K, et al. Cost-effectiveness of primary screening for CKD: A systematic

review. Am J Kidney Dis 2014;63:789-97. Crossref

38. Hwang SJ, Tsai JC, Chen HC. Epidemiology, impact and

preventive care of chronic kidney disease in Taiwan.

Nephrology (Carlton) 2010;15 Suppl 2:3-9. Crossref

39. Almaguer M, Herrera R, Alfonso J, Magrans C, Mañalich R,

Martínez A. Primary health care strategies for the prevention

of end-stage renal disease in Cuba. Kidney Int Suppl

2005;97:S4-10. Crossref

40. Alamaguer-Lopez M, Herrera-Valdez R, Diaz J, Rodriguez

O. Integration of chronic kidney disease prevention into

noncommunicable disease programs in Cuba. In: Garcia-Garcia G, Agodoa LY, Norris KC, editors. Chronic Kidney

Disease in Disadvantaged Populations. London: Elsevier Inc;

2017: 357-65. Crossref

41. US Department of Health and Human Services. Advancing

American Kidney Health. Available from: https://aspe.

hhs.gov/pdf-report/advancing-american-kidney-health.

Accessed 26 Sep 2019.

42. US Department of Health and Human Services. The Special

Diabetes Program for Indians. Estimates of Medicare savings.

Available from: https://aspe.hhs.gov/pdf-report/specialdiabetes-

program-indians-estimates-medicare-savings.

Accessed 26 Sep 2019.

43. Bello AK, Nwankwo E, El Nahas AM. Prevention of

chronic kidney disease: a global challenge. Kidney Int Suppl

2005;(98):S11-7. Crossref

44. James MT, Hemmelgarn BR, Tonelli M. Early recognition and

prevention of chronic kidney disease. Lancet 2010;375:1296-

309. Crossref

45. Cortés-Sanabria L, Cabrera-Pivaral CE, Cueto-Manzano AM, et al. Improving care of patients with diabetes and CKD:

a pilot study for a cluster-randomized trial. Am J Kidney Dis

2008;51:777-88. Crossref

46. Martínez-Ramírez HR, Jalomo-Martínez B, Cortés-Sanabria

L, et al. Renal function preservation in type 2 diabetes mellitus

patients with early nephropathy: a comparative prospective

cohort study between primary health care doctors and a

nephrologist. Am J Kidney Dis 2006;47:78-87. Crossref

47. Cueto-Manzano AM, Martínez-Ramírez HR, Cortes-

Sanabria L, Rojas-Campos E. CKD screening and prevention

strategies in disadvantaged populations. The role of primary

health care professionals. In: Garcia-Garcia G, Agodoa LY,

Norrris KC, editors. Chronic Kidney Disease in Disadvantaged

Populations. London: Elsevier, Inc; 2017: 329-35. Crossref

48. Tapia-Conyer R, Gallardo-Rincon H, Betancourt-Cravioto M.

Chronic kidney disease in disadvantaged populations: Online

educational programs for NCD prevention and treatment.

In: Garcia-Garcia G, Agodoa LY, Norris KC, editors. Chronic

Kidney Disease in Disadvantaged Populations. London:

Elsevier, Inc; 2017: 337-45. Crossref

49. Bello AK, Levin A, Manns BJ, et al. Effective CKD care in

European countries: challenges and opportunities for health

policy. Am J Kidney Dis 2015;65:15-25. Crossref

50. Sharif MU, Elsayed ME, Stack AG. The global nephrology

workforce: emerging threats and potential solutions! Clin

Kidney J 2016;9:11-22. Crossref

51. Naicker S, Eastwood JB, Plange-Rhule J, Tutt RC. Shortage

of healthcare workers in sub-Saharan Africa: a nephrological

perspective. Clin Nephrol 2010;74 Suppl 1:S129-33. Crossref

52. Cusumano AM, Rosa-Diez GJ, Gonzalez-Bedat MC. Latin

American Dialysis and Transplant Registry: Experience and

contributions to end-stage renal disease epidemiology. World

J Nephrol 2016;5:389-97. Crossref

53. Feehally J, Brusselmans A, Finkelstein FO, et al. Improving

global health: measuring the success of capacity building

outreach programs: a view from the International Society of

Nephrology. Kidney Int Suppl (2011) 2016;6:42-51. Crossref

54. Harris DC, Dupuis S, Couser WG, Feehally J. Training

nephrologists from developing countries: does it have a

positive impact? Kidney Int Suppl (2011) 2012;2:275-8. Crossref

55. Morbidity and mortality of renal dialysis: an NIH consensus

conference statement. Consensus Development Conference

Panel. Ann Intern Med 1994;121:62-70. Crossref

56. Garcia-Garcia G, Martinez-Castellanos Y, Renoirte-Lopez

K, et al. Multidisciplinary care for poor patients with chronic

kidney disease in Mexico. Kidney Int Suppl (2011) 2013;3:178-

83. Crossref

57. Stanifer JW, Von Isenburg M, Chertow GM, Anand S.

Chronic kidney disease care models in low- and middleincome

countries: a systematic review. BMJ Glob Health

2018;3:e000728. Crossref

58. Narva AS, Norton JM, Boulware LE. Educating patients about

CKD: the path to self-management and patient-centered care.

Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2016;11:694-703. Crossref

59. Schatell D. Web-based kidney education: supporting patient

self-management. Semin Dial 2013;26:154-8. Crossref