© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

MEDICAL PRACTICE

Biological disease-modifying antirheumatic

drugs in juvenile idiopathic arthritis of

polyarticular course, enthesitis-related arthritis,

and psoriatic arthritis: a consensus statement

Assunta CH Ho, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Paediatrics)1; SN Wong, MB, BS, FHKAM (Paediatrics)2; Lettie CK Leung, MB, BS (Syd), FHKAM (Paediatrics)3; Winnie KY Chan, MB, BS, FHKAM (Paediatrics)4; Patrick CY Chong, MB, BS, FHKAM (Paediatrics)5; Niko KC Tse, MB, BS, FHKAM (Paediatrics)6; Roanna HM Yeung, MB, BS, FHKAM (Paediatrics)4; SY Kong, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Paediatrics)3; KP Lee, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Paediatrics)7

1 Department of Paediatrics, Prince of Wales Hospital, The Chinese

University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong

2 Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Tuen Mun Hospital,

Tuen Mun, Hong Kong

3 Department of Paediatrics, Kwong Wah Hospital, Yaumatei, Hong Kong

4 Department of Paediatrics, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Jordan, Hong

Kong

5 Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Queen Mary

Hospital, The University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

6 Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Princess Margaret

Hospital, Laichikok, Hong Kong

7 Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Pamela Youde

Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Chai Wan, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Assunta CH Ho (assuntaho@cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Objectives: Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is

the most common type of inflammatory arthritis

in children. Treatment options have been expanded

since the introduction of biologics, which are highly

effective. The existing local JIA treatment guideline

was published more than a decade ago, when use

of biologics was not as common. In this article, we

review the latest evidence on using biologics in three

JIA subtypes: JIA of polyarticular course (pcJIA),

enthesitis-related arthritis (ERA), and psoriatic

arthritis (PsA). Based on the latest information,

an update on eligibility, response assessment,

termination, and safety information for using

biologics in these patients was performed.

Consensus process: The JIA Work Group, which

consisted of nine paediatricians experienced in

managing JIA, was convened in 2016. Publications

before July 2017 were screened. Eligible articles were

clinical trials, extension studies, systemic reviews,

and recommendations from international societies

and regulatory agencies about the use of biologics in

pcJIA, ERA, and PsA. Evidence extraction, appraisal,

and drafting of propositions were performed by

two reviewers. Extracted evidence and drafted

propositions were presented and discussed at the

first two meetings. Overwhelming consensus was

obtained at the final meeting in May 2018. Seven practice consensus statements were formulated.

Regular review should be performed to keep the

practice evidence-based and up-to-date.

Introduction

Biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs

(DMARDs) were introduced for the treatment of

juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) in year 2000. They

are highly effective, especially for patients who are

refractory to conventional DMARDs (cDMARDs).

The current treatment algorithm for JIA in Hong

Kong was published more than a decade ago, when

the use of biologics was not as common.1 There has been a huge expansion in knowledge and approved

medications since then. An update of practice

based on the latest evidence is required, not only

for specialists but also paediatricians and family

physicians who may provide care to children with

JIA.

The Hong Kong Society for Paediatric Rheumatology commissioned the JIA Work Group

in 2016 to review this topic. The work group consists

of nine paediatricians experienced in managing JIA.

Our aims were: (1) to review the latest evidence

on biological DMARDs in polyarticular course JIA

(pcJIA, ie, those having arthritis affecting ≥5 joints

irrespective of subtype at onset), enthesitis-related

arthritis (ERA), and psoriatic arthritis (PsA); and (2)

to propose an updated practice consensus for using

biologics in these patients.

Methods

Articles about the use of biologics in pcJIA, ERA,

and PsA published in English before July 2017 were

identified by searching MEDLINE and PubMed.

The keywords used for searching included JIA, pcJIA, ERA, PsA, eoJIA (extended oligoarticular

arthritis), biologics, biological DMARDs, guidelines,

recommendation, practice review, registries, adverse

effects, malignancy, and infection. Publications

considered relevant were clinical trials (randomised

trials, reports on long-term extension phase of

clinical trials), open-label studies, results from

analysis of major registries, and recommendations

from international regulatory organisations (United

Kingdom: Clinical Commissioning Policy of National

Health Service, National Institute for Health and

Care Excellence; United States: American College of

Rheumatology [ACR]; Australia: the Pharmaceutical

Benefits Scheme, reimbursement programme for

biologics use). Article screening, grading of the

level of evidence, and propositions drafting were

performed by two reviewers. The extracted evidence

and draft propositions were presented to work group

members at the first meeting held in July 2017. They

were discussed and deliberated in a subsequent

meeting held in March 2018. At the final meeting in

May 2018, overwhelming consensus was reached on

seven practice consensus statements.

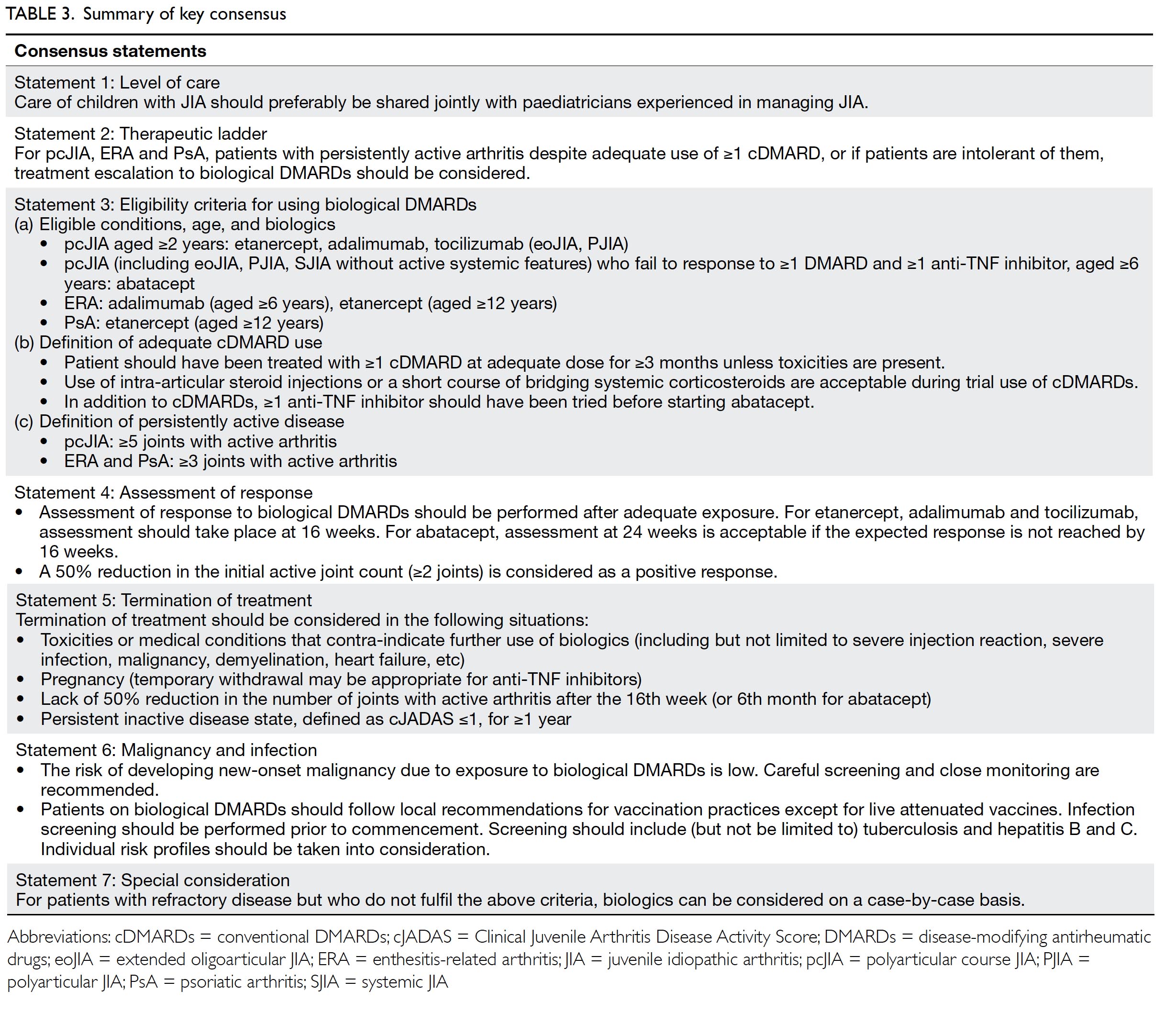

Statement 1: Level of care

Care of children with JIA should preferably be

shared jointly with paediatricians experienced in

managing JIA.

With modern treatment strategies, a high level

of disease control is possible. One study reported

that more than 70% of patients (except rheumatoid

factor positive polyarticular JIA) were able to reach

a clinically inactive disease state within 2 years.2 To

achieve the best outcome, care plans and treatment

targets should be carefully formulated together with

patients and paediatricians experienced in managing

JIA.

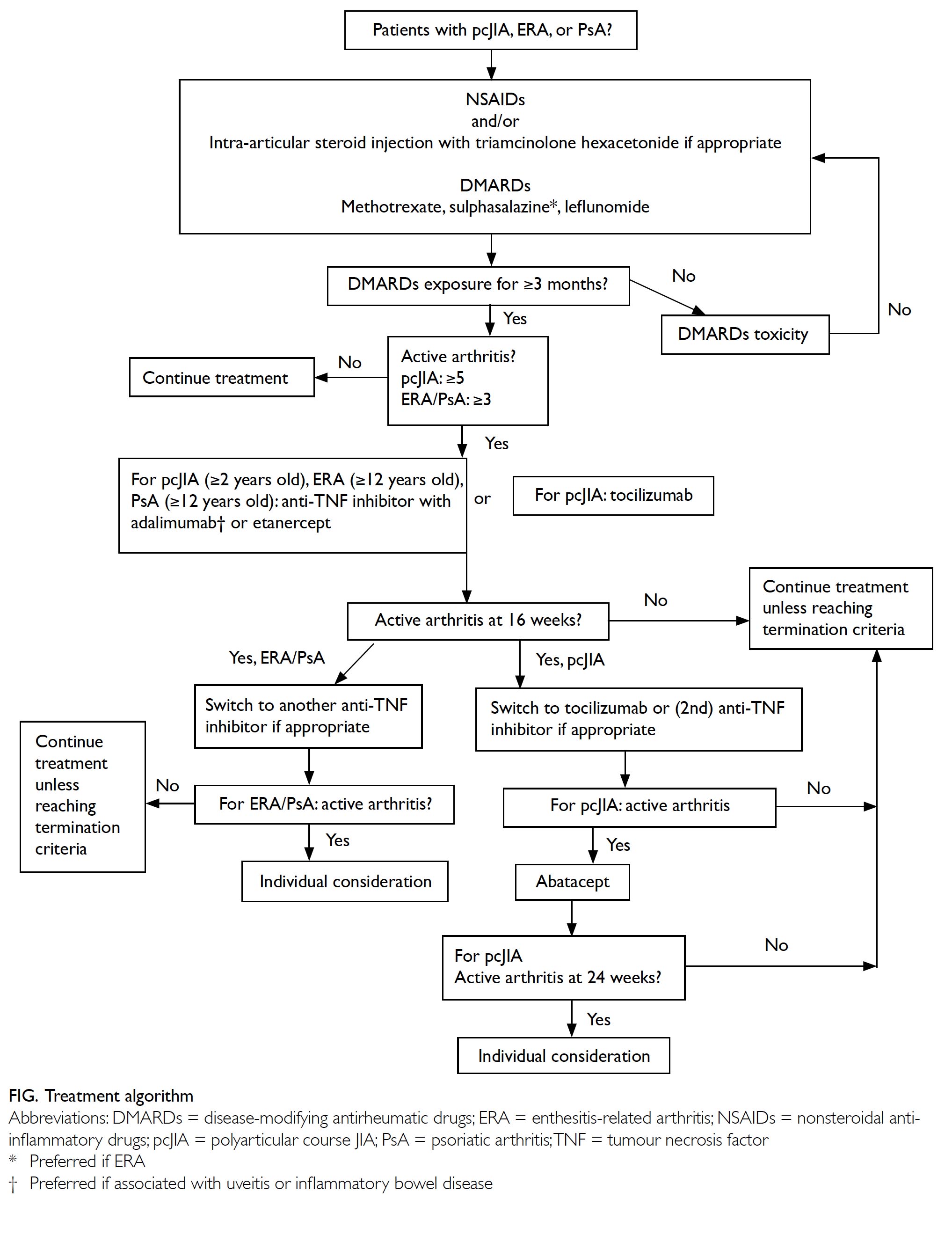

Statement 2: Therapeutic ladder

For pcJIA, ERA and PsA, patients with persistently

active arthritis despite adequate use of one or

more cDMARDs, or if patients are intolerant of

them, treatment escalation to biological DMARDs

should be considered.

Conventional DMARDs like methotrexate,

leflunomide, and sulphasalazine are effective in

treating pcJIA.3 4 5 6 The choice of cDMARDs usually

depends on JIA subtype and patient tolerance.

Nevertheless, some patients may not respond to

or may be intolerant of cDMARDs. Switching to

biologics should be considered in these cases.

Biological disease-modifying antirheumatic

drugs: evidence of effectiveness

Anti-tumour necrosis factor inhibitors

Etanercept

Etanercept is a chimeric fusion protein that acts as soluble TNF receptor. It is approved for use in

cases of: (1) pcJIA in children aged ≥2 years (Food

and Drug Administration [FDA] and European

Medicines Agency [EMA]) and (2) ERA and PsA in

children aged ≥12 years (EMA). The dose is 0.4 mg/kg

(max 25 mg) twice weekly or 0.8 mg/kg (max 50 mg)

once weekly subcutaneously.

Etanercept was the first anti-TNF inhibitor

approved for pcJIA. Its efficacy was demonstrated by

a randomised withdrawal trial7, in which 69 patients

with pcJIA aged 4 to 17 years who were refractory to

methotrexate were enrolled in the open-label lead-in

phase. Fifty one (74%) patients achieved an ACR 30

response at week 12. They were then randomised to

receive either etanercept or placebo for 16 weeks.

Etanercept was more effective in preventing arthritis

flares (28% vs 81%, P=0.003). The median time to

flare was significantly shorter in the placebo group

(28 days vs 116 days, P<0.001). Long-term data from

the extension phase confirmed the persistence of

efficacy.8

The use of etanercept in eoJIA, ERA, and PsA

was studied by Horneff et al.9 In all, 127 patients

(60 patients with eoJIA aged 2-17 years, 38 patients

with ERA aged 12-17 years, 29 patients with PsA

aged 12-17 years) were recruited in an open-label

multicentre study. All had persistently active disease

despite the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory

drugs (NSAIDs; for ERA) and DMARDs (for eoJIA,

ERA, and PsA). At week 12, 88.6% (95% confidence

interval [CI]=81.6%-93.6%) had attained ACR 30

response. The proportion of response was similar

across all three subtypes.

The efficacy of etanercept in ERA was further

evaluated. In a phase III double-blinded study,

41 patients aged 6 to 17 years with active disease

despite taking at least one NSAID and one DMARD

were recruited. They received open-label etanercept

for 24 weeks. An ACR 30 response was achieved

in 38 (93%). These patients were then randomised

to receive etanercept or placebo in the subsequent

24-week withdrawal phase. The odds for having a

flare was significantly higher in placebo group (odds

ratio=6, 95% CI=1.1-37, P=0.02).10

The use of etanercept has now been extended

to 2 years old.11 The efficacy of administrating at 0.8

mg/kg weekly has been shown to be comparable to

twice weekly dosing.12

Etanercept can be used concomitantly with

methotrexate or as monotherapy.13

Adalimumab

Adalimumab is a fully humanised monoclonal anti-

TNF antibody. It is approved for use in cases of: (1)

pcJIA in children aged ≥2 years (FDA and EMA) and

(2) ERA in children aged ≥6 years (EMA). The dose is

once every other week at 10 mg for 10 to <15 kg, 20

mg for 15 to <30 kg, and 40 mg for ≥30 kg.

Adalimumab was shown to be effective in

treating pcJIA by Lovell et al.14 In total, 171 patients

aged 4 to 17 years with active arthritis despite

taking NSAIDs or methotrexate were enrolled in

the 16-week open-label phase. In all, 94% of the

adalimumab-methotrexate group and 74% of the

adalimumab monotherapy group demonstrated

an ACR 30 response. In the 32-week randomised

withdrawal phase, the flare rate was significantly

lower for those who remained on adalimumab. The

results were more pronounced in patients receiving

concomitant methotrexate (flare in placebo and

methotrexate vs adalimumab and methotrexate: 65%

vs 37%, P=0.02; flare in placebo vs adalimumab: 71%

vs 43%, P=0.03). Efficacy was maintained in the long-term

extension phase.

Burgos-Vargas et al15 studied the effectiveness

of adalimumab in 46 patients with ERA. These

patients, aged 6 to 17 years, had active arthritis and

enthesitis. They were randomised to receive either

adalimumab or placebo. At week 12, the adalimumab

group had a significantly greater percentage decrease

in the number of active joints (-62.2% vs -11.6%,

P=0.039).

The safety and effectiveness of adalimumab in

children aged 2 to 4 years weighing <15 kg were also

demonstrated.16

Adalimumab can be used together with

methotrexate or as monotherapy.

T cell co-stimulation inhibitor

Abatacept

Abatacept is a co-stimulation modulator that binds to the cluster of differentiation (CD) 80 or CD 86

ligands of the antigen-presenting cell and interferes

with its interactions with T cells. Abatacept is

indicated for pcJIA in children aged ≥6 years who

are unresponsive to cDMARDs and at least one anti-TNF (EMA, FDA). The dose is 10 mg/kg (max 1g)

infusion on day 1, 15, 29, and then every 28 days.

The efficacy of abatacept in pcJIA was assessed

in a randomised withdrawal trial by Ruperto et al.17

The enrolled patients were aged 6 to 17 years with

active disease despite DMARDs including anti-TNF

inhibitors. Systemic JIA patients without systemic

manifestations were also eligible. Patients with ERA

or PsA were not included. Among the 190 recruited

patients, 27% had previously been exposed to anti-TNF therapy. At the end of the 4-month open-label

phase, 123 (65%) demonstrated an ACR 30 response.

After one patient left the study, the remaining 122

patients were randomised to receive abatacept (60

patients) or placebo (62 patients) for 6 months. The

flare rate of the abatacept group was significantly

lower than that of the placebo group (20% vs 53%,

P=0.0003). The hazard ratio for having a flare in the

abatacept group was 0.31 (95% CI=0.16-0.95). The

median time to flare was 6 months for placebo and

not assessable for abatacept because of an inadequate

number of events (P=0.0002). Among patients who

did not achieve ACR 30 at the end of the 4-month

open-label phase, half achieved ACR 30 after longer

exposure. By day 589 of the long-term extension

phase, the proportions of patients achieving ACR

30, 50, 70, 90, and 100 were 90%, 88%, 75%, 57%, and

39%, respectively.18

Abatacept can be used concomitantly with

methotrexate or as monotherapy.

Anti-interleukin 6 inhibitor

Tocilizumab

Tocilizumab is a humanised anti–interleukin 6

monoclonal antibody. It is indicated for pcJIA in

child aged ≥2 years (FDA, EMA). The dose is once

every 4 weeks intravenous infusion, 10 mg/kg for

<30 kg, 8 mg/kg for ≥30 kg.

Tocilizumab is another non-anti-TNF option

for pcJIA. In a phase 3, three-part randomised

controlled study (CHERISH), 188 patients aged

2 to 17 years with active disease received open-label

tocilizumab for 16 weeks. In all, 166 (88%)

achieved an ACR 30 response. A total of 163 were

then randomised to receive tocilizumab (n=82) or

placebo (n=81) for 24 weeks. Flares of JIA occurred

significantly less often in the tocilizumab group

(25.6% vs 48.1%, difference in means adjusted

for stratification -0.21; 95% CI= -0.35 to -0.08;

P=0.0024). Numerically more patients on concurrent

methotrexate achieved ACR 70 and 90 responses.19

Tocilizumab can be used concomitantly with

methotrexate or as monotherapy.

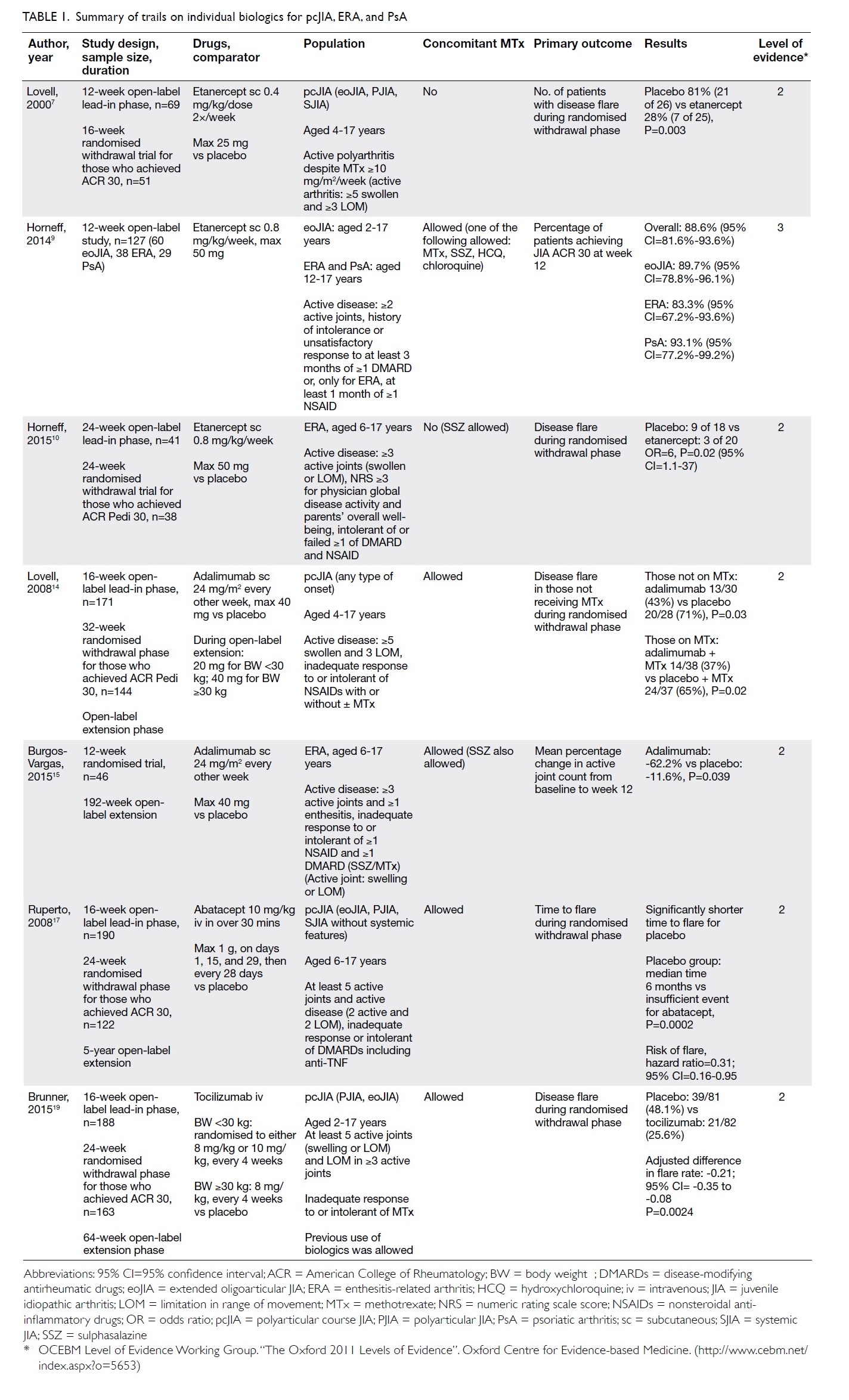

Systemic reviews of biologics

The short-term efficacies of biologics have been

confirmed by systemic reviews.20 21 22 While there have

been no head-to-head trials between individual

biologics, analysis with indirect comparisons has not

shown obvious differences in efficacy. Longer-term

data (mainly for etanercept) and reports from major

registries also confirm biologics’ effectiveness and

safety.23 The results of clinical trials are summarised

in Table 1.

Statement 3: Eligibility criteria for

using biological disease-modifying

antirheumatic drugs

The work group achieved overwhelming consensus

on the following eligibility criteria.

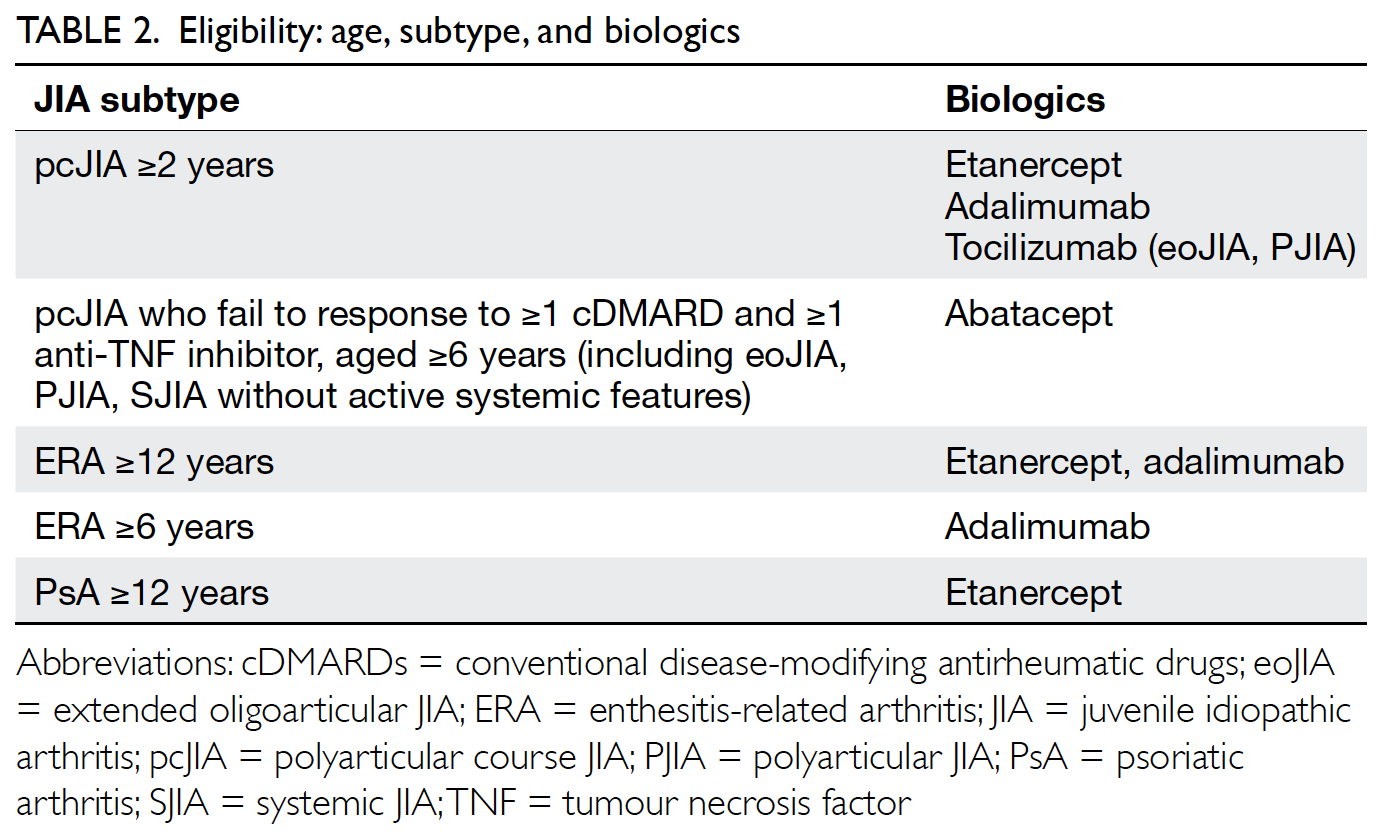

Eligible conditions, age, and biologics

Table 2 lists the JIA subtypes and the corresponding biological DMARDs indicated. Anti-TNF inhibitors

are usually the first biologics to commence, except in

systemic JIA. The decision of which biologic to start

also depends on JIA subtype, the presence of extra-articular

manifestations (eg, uveitis, inflammatory

bowel disease), patient preferences, etc.24 25

Definition of adequate use of conventional

disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs

It usually takes 6 to 8 weeks before the effects

of cDMARDs can be seen. “Adequate cDMARDs

exposure” is often defined as at least 3 months.

However, if one develops significant intolerance or

toxicities during trial of cDMARDs, use of biologics

should be considered earlier.

Definition of persistently active disease

“Active arthritis” is defined as swelling, with

or without limitation in movement. Joints with

limitation in movement due to pain or tenderness

are also considered as “active”, especially those in

which swelling is difficult to assess.

When deciding the number of joints required

to define active disease, the work group adopted the

commonly used inclusion criteria of the clinical trials.

In view of the fact that the disease characteristics

(eg, number of joints involved, clinical course,

medication indicated) are somewhat different for ERA and PsA, the work group considered it more

appropriate to have seperate definitions for ERA and

PsA.

Statement 4: Assessment of

response

Patients usually experience improvement

within or around 3 months after commencement.

The exception is abatacept, which may take a bit

longer to achieve the desired therapeutic effect.20

The definition of positive response is

extrapolated from Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme.

It is easy to apply and does not require inflammatory

markers like erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive

protein, as they are not always elevated.

Statement 5: Termination of

treatment

Termination of treatment should be considered in

the following situations:

The above termination criteria represent

the common “end points” for stopping biologics,

ie, the development of side-effects, conditions

contra-indicated for use of biologics, or continuous

remission of the index disease.

Pregnancy is no longer an absolute contraindication

in adult patients with rheumatoid arthritis

or ankylosing spondylitis who are receiving anti-TNF inhibitors. Temporary withdrawal, however,

is necessary for some agents. There have been no

recent updates from international organisations on

the use of biologics in pregnant patients with JIA.

This issue should be revisited during the next update.

Several definitions are used to describe

treatment response and disease remission in JIA.26 The Clinical Juvenile Arthritis Disease Activity Score

is a composite measurement that evaluates three

variables: active joint count, patient’s/parents’ global

well-being score, and physician’s global disease

activity score (both on visual analogue scales).

It has been shown to outperform other activity

measurements in predicting the need of escalation

to anti-TNF inhibitors.27 For both oligoarticular

arthritis and pcJIA, a score of ≤1 signifies inactive

disease.

Statement 6: Malignancy and

infection

In 2008, the FDA issued a black box warning

about the development of malignancy, particularly

lymphoproliferative types, in 48 children after

commencement of anti-TNF inhibitors between

2001 and 2008.28 In recent years, researchers

investigated the risk of malignancy by analysing

data generated from major registries and medical

reimbursement databases. These data suggested that

TNF inhibition alone is probably not causing the

apparent increase in incident malignancy. Instead,

those children’s background risk might have already

been elevated compared with that of the general

population. Nevertheless, much longer-term data

on larger patient samples are needed, as both cancer

and JIA are rare in children.29 30 31

Data on the associations between malignancy

and other non-anti-TNF biologics are still lacking.

Careful screening prior to commencement and

ongoing surveillance are necessary.

As for infection, biological DMARDs are

generally safe. Most infections associated with the

use of biologics are mild. Nevertheless, data from

registries and medical insurance databases did

show an increase in bacterial or serious infections

associated with TNF inhibition.32 33 34 Tuberculosis is a

genuine concern in our locality.35 36 Careful screening

and follow-up according to individual risk profiles

is strongly encouraged. The baseline infection

screening should include, but not be limited to, the

following:

While live attenuated vaccines should be

avoided during use of biologics, patients should

follow local guidelines for non-live vaccines.

Statement 7: Special consideration

The work group is aware that some patients

who do not fulfil the above criteria might still benefit

from biologics. These patients include those with

persistently active and disabling multiple enthesitis

or sacroiliitis despite NSAIDs and DMARDs or

oligoarticular JIA with severely active arthritis

and has exhausted treatment modalities including

intra-articular steroid injections and multiple

cDMARDs, etc. The use of biologics can be considered after careful assessment on a case-bycase basis.

Looking ahead: new indications

after the review period

The indications for use of biological DMARDs

have been expanding. For example, subcutaneous abatacept and tocilizumab are approved for pcJIA in

patients aged ≥2 years in the United States.37 38 39 The

ACR is also preparing a new update of the 2011 and

2013 guidelines. A review of the practice should be

performed regularly.

Conclusion

The use of biological DMARDs has greatly improved

the management of patients with JIA. Both patients and physicians could benefit from incorporating

the latest and best available evidence into disease

management. Periodic review should be performed

to keep clinical practice evidence-based and up-to-date.

Author contributions

All the authors contributed substantially to conception and design, acquisition and analysis of data, drafting and revising the article, and approval of the version to be published.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have no competing interest in the products

mentioned in this paper.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any funding

agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

1. Lee TL, Lau YL, Chan W, et al. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis in Hong Kong and its current management. HK J Paediatr (new series) 2003;8:21-30. >

2. Guzman J, Oen K, Tucker LB, et al. The outcomes of juvenile idiopathic arthritis in children managed with contemporary treatments: results from the ReACCh-Out cohort. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:1854-60. Crossref

3. Giannini EH, Brewer EJ, Kuzmina N, et al. Methotrexate in resistant juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Results of the U.S.-U.S.S.R. double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The Pediatric Rheumatology Collaborative Study Group and The Cooperative Children's Study Group. N Engl J Med 1992;326:1043-9. Crossref

4. Woo P, Southwood TR, Prieur AM, et al. Randomised placebo-controlled, crossover trial of low-dose oral methotrexate in children with extended oligoarticular or systemic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2000;43:1849-57. Crossref

5. Silverman E, Mouy R, Spiegel L, et al. Leflunomide or methotrexate for juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 2005;352:1655-66. Crossref

6. van Rossum MA, Fiselier TJ, Franssen MJ, et al. Sulfasalazine in the treatment of juvenile chronic arthritis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study. Dutch Juvenile Chronic Arthritis Study Group. Arthritis Rheum 1998;41:808-16. Crossref

7. Lovell DJ, Giannini EH, Reiff A, et al. Etanercept in children with polyarticular juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Pediatric Rheumatology Collaborative Study Group. N Engl J Med 2000;342:763-9. Crossref

8. Lovell DJ, Reiff A, Ilowite NT, et al. Safety and efficacy of up to eight years of continuous etanercept therapy in patients with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:1496-504. Crossref

9. Horneff G, Burgos-Vargas R, Constantin T, et al. Efficacy and safety of open-label etanercept on extended oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis, enthesitis- related arthritis and psoriatic arthritis: part 1 (week 12) of the CLIPPER study. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:1114-22. Crossref

10. Horneff G, Foeldvari I, Minden K, et al. Efficacy and safety of etanercept in patients with the enthesitis-related arthritis category of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2015;67:2240-9. Crossref

11. Windschall D, Horneff G. Safety and efficacy of etanercept and adalimumab in children aged 2 to 4 years with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Clin Rheumatol 2016;35:2925-31. Crossref

12. Horneff G, Ebert A, Fitter S, et al. Safety and efficacy of once weekly etanercept 0.8 mg/kg in a multicenter 12 week trial in active polyarticular course juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009;48:916-9. Crossref

13. Horneff G, De Bock F, Foeldvari I, et al. Safety and efficacy of combination of etanercept and methotrexate compared to treatment with etanercept only in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA): preliminary data from the German JIA Registry. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:519-25. Crossref

14. Lovell DJ, Ruperto N, Goodman S, et al. Adalimumab with or without methotrexate in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 2008;359:810-20. Crossref

15. Burgos-Vargas R, Tse SM, Horneff G, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter study of adalimumab in pediatric patients with enthesitis-related arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2015;67:1503-12. Crossref

16. Kingsbury DJ, Bader-Meunier B, Patel G, Arora V, Kalabic J, Kupper H. Safety, effectiveness, and pharmacokinetics of adalimumab in children with polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis aged 2 to 4 years. Clin Rheumatol 2014;33:1433-41. Crossref

17. Ruperto N, Lovell DJ, Quartier P, et al. Abatacept in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled withdrawal trial. Lancet 2008;372:383-91. Crossref

18. Ruperto N, Lovell DJ, Quartier P, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of abatacept in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2010;62:1792-802. Crossref

19. Brunner HI, Ruperto N, Zuber Z, et al. Efficacy and safety of tocilizumab in patients with polyarticular-course juvenile idiopathic arthritis: results from a phase 3, randomized, double-blind withdrawal trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:1110-7. Crossref

20. Shepherd J, Cooper K, Harris P, Picot J, Rose M. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of abatacept, adalimumab, etanercept and tocilizumab for treating juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a Crossref

21. Ungar WJ, Costa V, Burnett HF, Feldman BM, Laxer RM. The use of biologic response modifiers in polyarticular- course juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2013;42:597-618. Crossref

22. Otten MH, Anink J, Spronk S, van Suijlekom-Smit LW. Efficacy of biological agents in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a systematic review using indirect comparisons. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:1806-12. Crossref

23. Klotsche J, Niewerth M, Haas JP, et al. Long-term safety of etanercept and adalimumab compared to methotrexate in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA). Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:855-61. Crossref

24. Anink J, Otten MH, Gorter SL, et al. Treatment choices of paediatric rheumatologists for juvenile idiopathic arthritis: etanercept or adalimumab? Rheumatology (Oxford) 2013;52:1674-9. Crossref

25. Kearsley-Fleet L, Davies R, Baildam E, et al. Factors associated with choice of biologics among children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: results from two UK paediatric biologic registers. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2016;55:1556-65. Crossref

26. Smith EM, Foster HE, Beresford MW. The development and assessment of biological treatments for children. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2015;79:379-94. Crossref

27. Swart JF, van Dijkhuizen EH, Wulffraat NM, de Roock S. Clinical juvenile arthritis disease activity score proves to be a useful tool in treat-to-target therapy in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2018;77:336-42. Crossref

28. Diak P, Siegel J, La Grenada L, Choi L, Lemery S, McMahon A. Tumor necrosis factor alpha blockers and malignancy in children: forty-eight cases reported to the Food and Drug Administration. Arthritis Rheum 2010;62:2517-24. Crossref

29. Beukelman T, Haynes K, Curtis JR, et al. Rate of malignancy associated with juvenile idiopathic arthritis and its treatment. Arthritis Rheum 2012;64:1263-71. Crossref

30. Ruperto N, Martini A. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis and malignancy. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2014;53:968-74. Crossref

31. Mannion ML, Beukelman T. Risk of malignancy associated with biologic agents in pediatric rheumatic disease. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2014;26:538-42. Crossref

32. Beukelman T, Xie F, Chen L, et al. Rates of hospitalized bacterial infection associated with juvenile idiopathic arthritis and its treatment. Arthritis Rheum 2012;64:2773- 80. Crossref

33. Davies R, Southwood TR, Kearsley-Fleet L, Lunt M, Hyrich KL; British Society for Paediatric and Adolescent Rheumatology Etanercept Cohort Study. Medically significant infections are increased in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis treated with etanercept: results from the British Society for Paediatric and Adolescent Rheumatology Etanercept Cohort Study. Arthritis Rheumatol 2015;67:2487-94. Crossref

34. Becker I, Horneff G. Risk of serious infection in juvenile idiopathic arthritis patients associated with tumor necrosis factor inhibitors and disease activity in the German biologic in pediatric rheumatology registry. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2017;69:552-60. Crossref

35. Mok CC, Tam LS, Chan TH, Lee GK, Li EK; Hong Kong Society of Rheumatology. Management of rheumatoid arthritis: consensus recommendations from the Hong Kong Society of Rheumatology. Clin Rheumatol 2011;30:303-12. Crossref

36. Wan R, Mok CC. The Hong Kong Society of Rheumatology Biologics Registry: Updated Report (May 2016). HK Bulletin Rheum Dis 2016;16:24-6. Crossref

37. Brunner HI, Tzaribachev N, Vega-Cornejo G, et al. Subcutaneous abatacept in patient with polyarticular- course juvenile idiopathic arthritis: results from a phase III open-label study. Arthritis Rheumatol 2018;70:1144-54. Crossref

38. Brunner H, Ruperto N, Martini A, et al. Identification of optimal subcutaneous doses of tocilizumab in children with polyarticular course juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2017;69(Suppl 4):Abstract 41.

39. De Benedetti F, Ruperto N, Lovell D, et al. THU0503 identification of optimal subcutaneous (SC) doses of tocilizumab in children with polyarticular-course juvenile idiopathic arthritis (PCJIA). Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76(Suppl 2):396. Crossref