© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

REMINISCENCE: ARTEFACTS FROM THE HONG KONG MUSEUM OF

MEDICAL SCIENCES

Drainage apparatus for treating pneumothorax

Harry YJ Wu, MD, DPhil

Medical Ethics and Humanities Unit, Li Ka Shing

Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

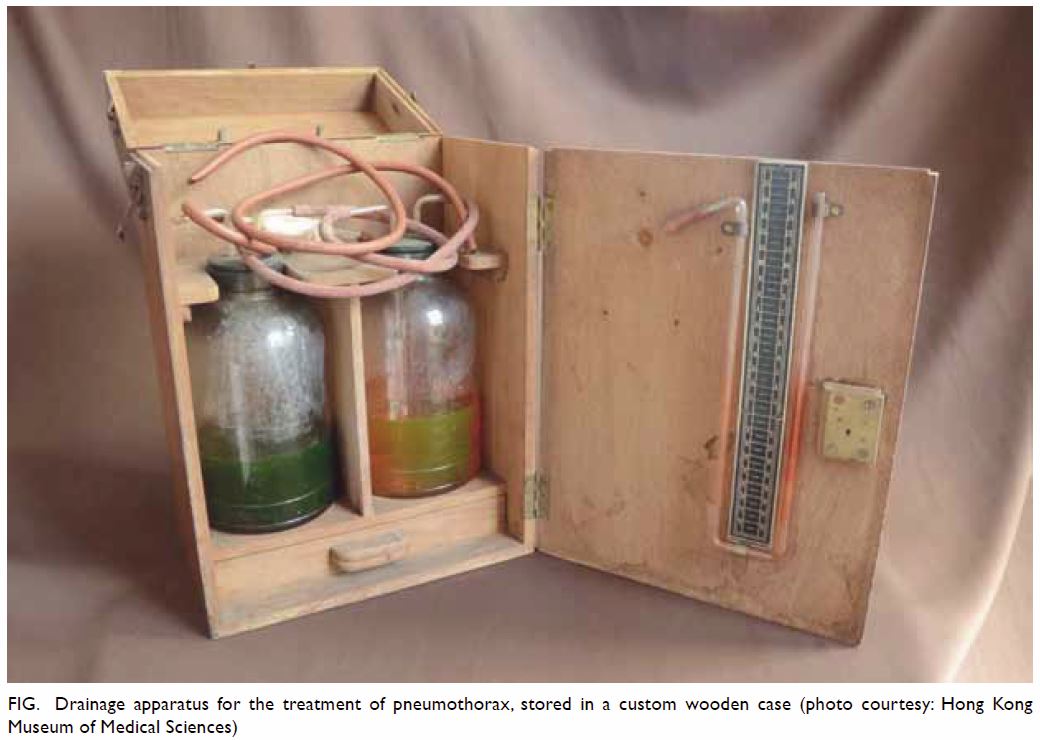

This drainage apparatus (Fig), collected by the Hong Kong Museum of Medical

Sciences and stored in a custom wooden case, is not an uncommon artefact.

It does, however, tell a distinctive story of Hong Kong people’s lungs.

The apparatus was donated by Dr Chiu Kwong Yu in 1999 and consists of two

1-L glass bottles containing sterile solutions, each measuring 21 cm tall

and 11.50 cm in diameter. The fluid in two bottles has deteriorated over

time and become darkened. Attached to the case door is a glass barometer

about 26 cm long. Under the glass bottles is a small drawer that used to

contain consumables, such as syringes, needles, scalpels, and blades. The

apparatus was used as a closed drainage system, mainly for the treatment

of pneumothorax and other conditions that require chest drainage, such as

pleural effusion and haemothorax. The portable design made it a practical

device that could be operated at the bedside.

Figure. Drainage apparatus for the treatment of pneumothorax, stored in a custom wooden case (photo courtesy: Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences)

Pneumothorax is a common lung condition. When a

pneumothorax occurs, the negative pressure in the pleural cavity is

disrupted, resulting in respiratory distress. If the condition is mild, a

small amount of fluid or air may be absorbed by the body after sufficient

rest. However, in a more severe situation, a drainage system is required

to prevent the lung from collapsing. Such treatment, employing a siphon

effect, can be dated to the late 19th century. In one of the earliest

documented cases in 1875, the German internist Gotthard Bülau described

using drainage to treat an empyema as an alternative to the then-popular

rib resection. He first used a trocar to puncture the pleural space and

then introduced a rubber catheter with a distal clamp to create a closed

water-seal system. The end of the catheter was immersed in a bottle

one-third full of antiseptic solution and then unclamped, resulting in a

siphon drainage apparatus and allowing pus to flow from the chest cavity.1

In modern times, several basic components are

needed to drain the fluid or air out of a pleural cavity. This usually

comprises a closed sterile and disposable system containing one or

multiple chambers with a one-way valve that can prevent return of air or

fluid into the patient. The main part of the apparatus collected by the

museum was manufactured by Kelvin & Hughes, a British company still in

business that specialises in the design and manufacture of instruments

related to navigation. However, the spindle-shaped glass compartment

containing two Chinese characters shows clear signs that the entire

apparatus might be a convenient assemblage of various sources. It was

likely used most extensively in the 1960s; in 1963, closed thoracotomy

drainage with a Foley catheter and two-bottle suction system was advocated

as the preferred treatment for pneumothorax and significant haemothorax.2 While in use, the two bottles and

spindle-form glass device containing sterilised cotton wool were connected

by rubber tubes. One end of the apparatus connected the chest catheter

that was inserted into the patient’s pleura. The treatment could last from

1 day to 2 weeks, depending on how well the patient responded to the

procedure. X-ray plain films were sometimes useful for doctors to evaluate

the remaining air or fluid in the pleura.

In the early days of Hong Kong’s history, certain

populations were more prone to developing pneumothorax. Resulting from

poor sanitation and occupational hazards, these were mostly patients with

more fragile lung conditions, such as those living with tuberculosis or

pneumoconiosis. It is also worth noting that, from the 1930s to the 1950s,

pneumothorax was employed as a treatment for tuberculosis. Before the

advent of anti-tuberculosis drugs, there was no specific treatment for

this infection, although surgical treatment could be offered in some early

cases. In the 1930s, the three most commonly performed operations were

sectioning of the phrenic nerve, creation of an artificial pneumothorax,

and thoracoplasty by removal of some ribs.3

The Annual Medical Report of the government for 1934 reported that the

University Medical Unit at Government Civil Hospital had started a special

clinic for artificial pneumothorax of pulmonary tuberculosis cases.4 In 1938, artificial pneumothorax treatment was carried

out in all suitable male cases at Queen Mary Hospital with ‘gratifying

results’.5 Such treatment gradually

became less common in the 1950s, owing to the availability and

effectiveness of anti-tuberculosis medication. However, it is

understandable that pleural drainage might have continued to be used

extensively, because of the high incidence of pneumothorax and lung cavity

infection among the many tuberculosis patients at that time.

In modern times, treatment for pneumothorax is no

longer complex. Most spontaneous pneumothorax patients will recover with

sufficient bed rest and nutrition support. The most commonly used device

for drainage is a plastic three-chamber unit. These include a collection

chamber, a water-seal chamber, and a suction control chamber, which are

interconnected. Despite international guidelines now advocating the use of

simple aspiration and small-bore chest catheters, in Hong Kong,

intercostal chest tube insertion remains popular.6

Therefore, this drainage apparatus represents, not an outdated practice,

but conceivably only a change in materials.

References

1. Meyer JA. Gotthard Bülau and closed

water-seal drainage for empyema, 1875-1891. Ann Thorac Surg 1989;48:597-9.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0003-4975(10)66876-2

2. Felton WL 2nd. Initial evaluation and

management of the patient with a chest injury. Am J Surg 1963;105:445-53.

Crossref

3. Li SF. Indications, contraindications

and end results in the surgical treatment of pulmonary TB. Caduceus

1931;10:167-77.

4. Wong TW. Plombage treatment for

pulmonary tuberculosis in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J 2014;20:268. Crossref

5. Wilkinson PB. Report of the University

Professorial Unit. Annual Medical Report for the Year Ending. 1938: 77.

6. Chan JW, Ko FW, Ng CK, et al. Management

of patients admitted with pneumothorax: a multi-centre study of the

practice and outcomes in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J 2009;15:427-33.