Hong

Kong Med J 2019 Jun;25(3):222–7 | Epub 10 Jun 2019

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

MEDICAL PRACTICE

Hong Kong needs a territory-wide registry for

out-of-hospital cardiac arrest

CT Lui, FHKCEM, FHKAM (Emergency Medicine)1;

CL Lau, FHKCEM, FHKAM (Emergency Medicine)1; Axel YC Siu,

FHKCEM, FHKAM (Emergency Medicine)2; KL Fan, FHKCEM, FHKAM

(Emergency Medicine)3; LP Leung, FHKCEM, FHKAM (Emergency

Medicine)4

1 Accident and Emergency Department,

Tuen Mun Hospital, Tuen Mun, Hong Kong

2 Accident and Emergency Department,

Ruttonjee Hospital, Wanchai, Hong Kong

3 Accident and Emergency Department, The

University of Hong Kong–Shenzhen Hospital, Shenzhen, China

4 Emergency Medicine Unit, The

University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr CT Lui (luict@ha.org.hk)

Abstract

Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) is an

urgent disease entity, and the outcomes of OHCA are poor. This causes a

significant public health burden, with loss of life and productivity

throughout society. Internationally, successful programmes have adopted

various survival enhancement measures to improve outcomes of

OHCA. A territory-wide organised survival enhancement campaign is

required in Hong Kong to maintain OHCA survival rates that are

comparable to those of other large cities. One key component is to

establish an OHCA registry, such as those in Asia, the United States,

Europe, Australia, and New Zealand. An OHCA registry can provide

benchmarking, auditing, and surveillance for identification of weak

points within the chain of survival and evaluation of the effectiveness

of survival enhancement measures. In Hong Kong, digitisation of records

in prehospital and in-hospital care provides the infrastructure for an

OHCA registry. Resources and governance to maintain a sustainable OHCA

registry are necessary in Hong Kong as the first step to improve

survival and outcomes of OHCA.

Background

Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) and sudden

cardiac death (SCD) are significant healthcare challenges and public

health burdens worldwide.1 It has

been estimated that around half of cardiovascular mortalities present as

SCD.2 Premature death may be caused

by OHCA and SCD, particularly in cases involving children, adolescents,

and young adults. The burden of premature death due to OHCA is on the

magnitude of millions of years of potential life lost, and this is the

third leading cause of years of potential life lost following cancer and

heart disease.1

In Hong Kong, more than 5000 OHCA cases with

attempted resuscitation occur annually.3

The incidence rate of OHCA in 2012 was reported to be 72 per 100 000

population. Although the incidence is low, the prognosis of OHCA is

generally poor. Worldwide, the survival rate of OHCA is 2% to 11%.4 In Hong Kong, a 2017 territory-wide study reported a

survival rate of 2.3% and a neurologically favourable survival rate of

1.5%.3 Reported survival rates of

OHCA in other parts of the world are heterogeneous, with 0.5%-8.5%

reported in Asian countries,5 8.5%

in the US,6 and 10.3% in Europe.7 The survival rate of OHCA in Hong

Kong is low compared with other cities or countries.

Strategies to enhance out-of-hospital cardiac arrest

survival

To maximise the effectiveness of any efforts to

improve OHCA outcomes, a well-organised territory-wide survival

enhancement campaign covering public, prehospital, and in-hospital

resuscitative care for OHCA would be optimal.8

9 In the public dimension,

fostering public awareness, enhancement of rate of good-quality bystander

cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR),10

and a territory-wide public access defibrillation programme11 have been the main pillars of enhancement of survival

of OHCA. In Hong Kong, there have been investigations on the availability

and accessibility of defibrillators in the community.12 13 However,

an organised public access programme is still lacking. In terms of

prehospital and in-hospital measures, shorter response times of emergency

medical systems, post-resuscitation targeted temperature management, and

comprehensive post-cardiac arrest care have proven to be effective

measures to improve survival.8 14 A previous systematic review

based mainly on observational data and small-scale trials suggested that

prehospital epinephrine produced no improvement in rate of survival to

hospital discharge.15 A recently

published large-scale trial demonstrated that epinephrine increased the

rate of survival to hospital discharge while increasing the rate of severe

neurological injury in survivors.16

Need for a cardiac arrest registry

Interpretation and comparison of survival rates of

OHCA between cities is complicated by various factors, including variation

in reporting mechanisms, reporting definitions, and prehospital care

models, particularly the practice of prehospital termination of

resuscitation at arrest scenes. The International Liaison Committee on

Resuscitation has defined a standardised style of resuscitation outcome

reports with definitions of parameters.17

The Utstein-style guidelines provide a standardised and harmonised

framework for comparison and benchmarking of emergency medical services

(EMS) systems.17 18 More importantly, epidemiological data on cardiac

arrest provide insight about local systems for management of cardiac

arrest and provide feedback to influence change in systems for enhancing

survival. In 2010, the American Heart Association (AHA) recognised and

reinforced the importance of data collection about OHCA and the

establishment of cardiac arrest registries. The AHA identified and defined

the essential core elements of a high-quality resuscitation system:

measurement, benchmarking, and providing feedback for change. Experts have

recommended that OHCA events become reportable events.19 In the last decade, there have been worldwide efforts

to establish regional cardiac arrest registries in various cities and

countries, including Japan, Singapore, South Korea, Sweden, and the United

Kingdom. There have been collaborative registries in Asia (The Pan-Asian

Resuscitation Outcomes Study), Europe (European Registry of Cardiac

Arrest), the US (Cardiac Arrest Registry to Enhance Survival), and

Australia, and New Zealand (Australian Resuscitation Outcomes Consortium

epidemiological registry). As OHCA is an important public health burden,

there is room for improvement in Hong Kong to enhance the survival rate of

OHCA, and there is scientific support for strategies and measures to

improve the outcomes of OHCA. What is missing in Hong Kong is a

well-organised survival enhancement campaign, together with a

territory-wide cardiac arrest registry. A cardiac arrest registry is a

non-replaceable element of continuous surveillance, identification of weak

points in the chain of survival, and evaluation of the effectiveness of

newly implemented survival enhancement measures.

Value of a cardiac arrest registry

As an indicator of the efficiency of emergency

healthcare systems and for benchmarking

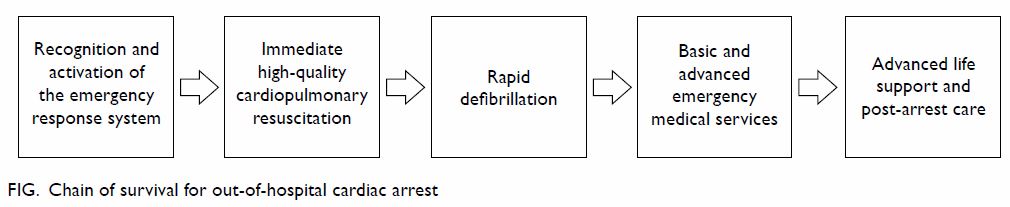

The outcomes and survival rate of OHCA depend on

the chain of survival (Fig). The survival rate and outcomes of OHCA are not

performance indicators of prehospital EMS or emergency departments.

Instead, it is a composite indicator of community resilience and

effectiveness of EMS, advanced life support, and resuscitation in

emergency departments and post-arrest cardiac and intensive care. The

concept of community resilience, which has been supported by many experts

in resuscitation science, had been raised in recent years in management of

conditions where every second counts, such as OHCA.20 Early recognition and appropriate response by

laypersons is the first and most critical step, including EMS activation,

initiation of bystander CPR, and public access defibrillation. If these

initial steps of recognition and resuscitation are not performed well,

profound hypoxic-ischaemic insult to the brain and other major organs is

likely. No matter how hard the subsequent steps in the chain of survival

are, and regardless of the sophistication of advanced and post-arrest

care, the chance of survival and neurological integrity would be limited.

Without a registry, the resilience of Hong Kong and the efficiency of its

emergency healthcare system remain unclear.

Surveillance, audit, and feedback

The OHCA registry is a means of surveillance. The

US Cardiac Arrest Registry to Enhance Survival (CARES) generates reports

with trend analysis regularly. Any major changes in outcomes are

identified, with corresponding investigation and rectification of any

gaps. During audits, weak points of care in the chain of survival can be

identified, which would provide invaluable information for the planning of

a survival enhancement campaign. The AHA has recommended a complete audit

cycle of (1) measurement by a cardiac arrest registry; (2) benchmarking;

and (3) feedback and change. With the OHCA data, one could identify the

weakest link in the chain of survival. Targeted survival enhancement

measures can then be designed and implemented. For example, a local

cardiac arrest registry at the accident and emergency department of Tuen

Mun Hospital identified deficiencies in the availability and accessibility

of publicly accessible defibrillators.12

With the implementation of survival enhancement measures, longitudinal

data collected using the same collection methodology are required to

evaluate their effectiveness.

Evaluation of the effectiveness of survival enhancement

measures

Efficacy is the extent to which a treatment is

capable of bringing about its intended effect under ideal circumstances.

Most clinical trials nowadays have provided information on efficacy.

However, the translation of the effects into clinical practice is not

direct. Effectiveness is the extent to which a treatment achieves its

intended effect in usual clinical settings in daily practice, which is

addressed by studies with pragmatic design. Similar to numerous clinical

conditions, most studies of OHCA evaluate efficacy instead of

effectiveness. Effectiveness cannot be measured in controlled trials. The

observational data in cardiac arrest registries constitute an important

dimension to measure the effectiveness of survival enhancement measures.

In the past decade, there have been numerous improvements in community

engagement and prehospital and in-hospital care for OHCA in Hong Kong.

Community measures include the Heart-safe School Project by the Hong Kong

College of Cardiology,21 mass CPR

training organised by the Resuscitation Council of Hong Kong,22 and the CPR training programme for secondary school

students and domestic helpers by the Emergency Medicine Unit of the

University of Hong Kong. Prehospital improvement measures have included

universal application of external defibrillators, enhanced training of

ambulance crews, widespread prehospital use of laryngeal mask airways,

intravenous adrenaline, first dispatch firefighters, telephone CPR advice,

and enhanced diversion policy for cardiopulmonary arrest. In-hospital

innovations have included implementation of up-to-date advanced life

support care guidelines, use of end-tidal capnography for CPR feedback,

use of mechanical thumpers, extracorporeal CPR, and advancement in

post-arrest intensive and cardiac care. So far, all reports of

resuscitation outcomes of cardiac arrest in Hong Kong have been

cross-sectional. There are no longitudinal data reporting survival trends.

An OHCA registry provides insights into the effectiveness of these

measures in terms of changes in survival. The Japanese Nationwide public

access defibrillation programme, which employs the All-Japan Utstein

Registry of the Fire and Disaster Management Agency, recorded that the

rate of neurologically favourable survival rose from 1.6% to 4.3% in 5

years.11

Experience with cardiac arrest registries in other

cities and countries

The Pan-Asian Resuscitation Outcomes Study

The Pan-Asian Resuscitation Outcomes Study (PAROS)

collaborative network23 was

established in 2010 with a prospective multicentre registry of OHCA events

across the Asia-Pacific region. It was supported by the Singapore Clinical

Research Institute and followed the CARES method. With input from the US

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the PAROS database is

CARES-compatible. The Asian Emergency Medical Services Council adopted the

PAROS registry as one of its core activities. The PAROS network has now

grown into a consortium of nine participating regions and countries:

Australia, Japan, South Korea, Malaysia, Singapore, Taiwan, Thailand,

Turkey, and the United Arab Emirates. The registry includes a population

base of over 89 million. Each participating country is responsible for

administering its own data collection process, and all data are input via

a secure shared internet data capture system with a harmonised database

hosted by the Singapore Clinical Research Institute. The goals of the

network are to provide benchmarking against established registries, to

generate best practice protocols for EMS systems, and to impact community

awareness of emergency resuscitative care.

European Registry of Cardiac Arrest

In 2007, the European Resuscitation Council

initiated a campaign for Europe-wide collaboration on a European registry

to record and analyse cases of cardiac arrest. The European Resuscitation

Council set up a steering committee in 2008 focusing on the development of

the European Registry of Cardiac Arrest (EuReCa), and its objective is to

create a central quality management tool.24

The EuReCa collects data about resuscitative events episodically. The

EuReCa ONE, which included 27 European countries, gathered all

resuscitative events in October 2014.7

For EuReCa TWO, which covers resuscitation events from 1 October 2017 to

31 December 2017, data collection was completed by April 2018 and

publication of results is pending.

Cardiac Arrest Registry to Enhance Survival

The CARES was funded by the US CDC, the Canadian

Ontario Pre-hospital Advanced Life Support network, and the Resuscitation

Outcomes Consortium of North America.25

Its governance is provided by the US CDC and the Emory University School

of Medicine. It provides various platforms for input of standardised

parameters about OHCA events by the participating states. The data sources

include EMS providers, dispatch centres, and hospitals. The data are then

merged into a single event representing a resuscitative episode. The

registry provides a validated measurement tool with benchmarking

capability for continuous quality improvement. It consolidates

observations and conclusions from the collected data and publishes them in

the form of a Morbidity and Mortality Report,6

and the scientific evidence is integrated into the AHA’s resuscitation

guidelines. The CARES was developed as a low-cost, high-impact public

health surveillance system to identify the weakest links in the chain of

survival in participating states.

The Australian Resuscitation Outcome Consortium

Australian and New Zealand out-of-hospital cardiac arrest Epistry

The Australian Resuscitation Outcome Consortium

(Aus-ROC) was established as a National Health and Medical Research

Council Centres of Research Excellence in 2011. Its objective is to

increase research capacity and improve OHCA survival and outcomes. Six

previously established cardiac arrest registries in Australia and two in

New Zealand contributed the data to form the Aus-ROC epidemiological

registry (Epistry) in 2014. The Epistry represents approximately 63% of

the Australian population (23.5 million) and 100% of the New Zealand

population (4.5 million). The Epistry is coordinated and located at the

Aus-ROC administrative base in the School of Public Health and Preventive

Medicine at Monash University in Australia. Participating ambulance

service networks are responsible for the data collection and upload

through a web-based engine. An Epistry Management Committee was

established to serve as the governing agent. Annual benchmarking reports

are generated from the Epistry’s data and provided to the ambulance

services network and relevant bodies for continuous quality improvement.

Technical and operational readiness for a cardiac

arrest registry in Hong Kong

Hong Kong is technically ready for the

establishment of a territory-wide cardiac arrest registry. Clinical

documentation in the prehospital and in-hospital settings would provide

the basic technical infrastructure of the registry. Prehospital care for

patients with cardiac arrest is provided almost exclusively by the

ambulance service of the Fire Services Department, while the Government

Flying Service and St John’s ambulance service play a supplementary role.

The prehospital documentation is digitalised in the electronic Ambulance

Journey Record, where the parameters about cardiac arrest patients are

standardised and Utstein-compatible. Together with electronic hospital

databases and the electronic Accident and Emergency System project of the

Hospital Authority, merging and integration of prehospital and in-hospital

databases would provide a feasible infrastructure and backbone of the

cardiac arrest registry in Hong Kong.

The establishment of cardiac arrest registries may

be quite different from other existing healthcare registries in Hong Kong,

such as the Hong Kong Cancer Registry26

and the Hong Kong Renal Registry.27

The cardiac arrest registries involve various stakeholders including

emergency medical dispatchers, EMS systems, and acute hospitals. The

specialties of acute hospitals include emergency departments, and

intensive care, paediatric, cardiology and medical units. Expert input

from academic units and professional bodies such as the Hong Kong Academy

of Medicine and its Colleges, the Resuscitation Council of Hong Kong, and

universities is desirable.

Governance and a well-defined operational framework

of the OHCA registry are mandatory for sustainability and assurance of

data quality. Referring to the experience with collaborative registries in

the US, Europe, Asia, Australia, and New Zealand, it is reasonable to set

up a registry governing and management committee whose role is to oversee

areas such as setup, maintenance, data quality control, data privacy and

security, and data use and access. The registry committee might be led by

government bodies such as the Food and Health Bureau or co-governed with

academic bodies such as the Hong Kong College of Emergency Medicine or

universities. All relevant stakeholders should be involved in the registry

committee. One key enabler of a sustainable registry is personnel to

maintain it. With the digitisation of documentation in prehospital and

in-hospital records, the gap requiring manual data entry and manipulation

has been dramatically narrowed in recent years.

Setting up an OHCA registry alone does not improve

outcomes of patients with SCD. Survival enhancement campaigns and

strategies, perhaps led by the government, are required. A cardiac arrest

registry should be considered a starting point that provides data to

evaluate the effectiveness of measures adopted in survival enhancement

campaigns and strategies and to provide uniform benchmarking for quality

measurement.

Conclusion

With the growing public health burden of OHCA, Hong

Kong has an imminent need to establish a territory-wide cardiac arrest

registry. It can provide guidance and insight about the effectiveness of

survival enhancement measures. It also provides uniform benchmarking for

continuous quality improvement by both prehospital and in-hospital service

providers. Concerted efforts by various stakeholders from the government,

the Hospital Authority, and academia are necessary to make the registry a

reality.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the content of the

review article, drafting of the manuscript, and critical revision for

important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data,

contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and

take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any

funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

1. Stecker EC, Reinier K, Marijon E, et al.

Public health burden of sudden cardiac death in the United States. Circ

Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2014;7:212-7. Crossref

2. Mehra R. Global public health problem of

sudden cardiac death. J Electrocardiol 2007;40(6 Suppl):S118-22. Crossref

3. Fan KL, Leung LP, Siu YC.

Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in Hong Kong: a territory-wide study. Hong

Kong Med J 2017;23:48-53. Crossref

4. Berdowski J, Berg RA, Tijssen JG, Koster

RW. Global incidences of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and survival

rates: systematic review of 67 prospective studies. Resuscitation

2010;81:1479-87. Crossref

5. Ong ME, Shin SD, De Souza NN, et al.

Outcomes for out-of-hospital cardiac arrests across 7 countries in Asia:

The Pan Asian Resuscitation Outcomes Study (PAROS). Resuscitation

2015;96:100-8. Crossref

6. McNally B, Robb R, Mehta M, et al.

Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest surveillance—Cardiac Arrest Registry to

Enhance Survival (CARES), United States, October 1, 2005-December 31,

2010. MMWR Surveill Summ 2011;60:1-19.

7. Gräsner JT, Lefering R, Koster RW, et

al. EuReCa ONE-27 Nations, ONE Europe, ONE Registry: a prospective one

month analysis of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest outcomes in 27 countries

in Europe. Resuscitation 2016;105:188-95. Crossref

8. Perkins GD, Lockey AS, de Belder MA, et

al. National initiatives to improve outcomes from out-of-hospital cardiac

arrest in England. Emerg Med J 2016;33:448-51. Crossref

9. Scottish Government. Scottish

out-of-hospital cardiac arrest data linkage project: 2015/16-2016/17

results. Available from:

https://www.gov.scot/publications/scottish-out-hospital-cardiac-arrest-data-linkage-project-2015-16/pages/4/.

Accessed 30 Sep 2018.

10. Wissenberg M, Lippert FK, Folke F, et

al. Association of national initiatives to improve cardiac arrest

management with rates of bystander intervention and patient survival after

out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. JAMA 2013;310:1377-84. Crossref

11. Kitamura T, Iwami T, Kawamura T, et

al. Nationwide public-access defibrillation in Japan. N Engl J Med

2010;362:994-1004. Crossref

12. Ho CL, Lui CT, Tsui KL, Kam CW.

Investigation of availability and accessibility of community automated

external defibrillators in a territory in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J

2014;20:371-8. Crossref

13. Fan KL, Lui CT, Leung LP. Public

access defibrillation in Hong Kong in 2017. Hong Kong Med J

2017;23:635-40. Crossref

14. Lai H, Choong CV, Fook-Chong S, et al.

Interventional strategies associated with improvements in survival for

out-of-hospital cardiac arrests in Singapore over 10 years. Resuscitation

2015;89:155-61. Crossref

15. Atiksawedparit P, Rattanasiri S,

McEvoy M, Graham CA, Sittichanbuncha Y, Thakkinstian A. Effects of

prehospital adrenaline administration on out-of-hospital cardiac arrest

outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care 2014;18:463. Crossref

16. Perkins GD, Ji C, Deakin CD, et al. A

randomized trial of epinephrine in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. N Engl

J Med 2018;379:711-21. Crossref

17. Perkins GD, Jacobs IG, Nadkarni VM, et

al. Cardiac arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation outcome reports:

update of the Utstein resuscitation registry templates for out-of-hospital

cardiac arrest: a statement for healthcare professionals from a task force

of the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (American Heart

Association, European Resuscitation Council, Australian and New Zealand

Council on Resuscitation, Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada,

InterAmerican Heart Foundation, Resuscitation Council of Southern Africa,

Resuscitation Council of Asia); and the American Heart Association

Emergency Cardiovascular Care Committee and the Council on

Cardiopulmonary, Critical Care, Perioperative and Resuscitation.

Resuscitation 2015;96:328-40. Crossref

18. Jacobs I, Nadkarni V, Bahr J, et al.

Cardiac arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation outcome reports: update

and simplification of the Utstein templates for resuscitation registries.

A statement for healthcare professionals from a task force of the

International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (American Heart

Association, European Resuscitation Council, Australian Resuscitation

Council, New Zealand Resuscitation Council, Heart and Stroke Foundation of

Canada, InterAmerican Heart Foundation, Resuscitation Council of Southern

Africa). Resuscitation 2004;63:233-49. Crossref

19. Nichol G, Rumsfeld J, Eigel B, et al.

Essential features of designating out-of-hospital cardiac arrest as a

reportable event: a scientific statement from the American Heart

Association Emergency Cardiovascular Care Committee; Council on

Cardiopulmonary, Perioperative, and Critical Care; Council on

Cardiovascular Nursing; Council on Clinical Cardiology; and Quality of

Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. Circulation

2008;117:2299-308. Crossref

20. Rea TD, Page RL. Community approaches

to improve resuscitation after out-of-hospital sudden cardiac arrest.

Circulation 2010;121:1134-40. Crossref

21. The Hong Kong Jockey Club Charities

Trust. Hong Kong College of Cardiology. The Jockey Club ‘Heart-safe

School’ Project. Available from:

http://www.heartsafeschool.org.hk/aboutus.aspx. Accessed 30 Sep 2018.

22. Resuscitation Council of Hong Kong.

Useful information. The Jockey Club ‘Heart-safe School’ Project. Available

from: http://www.rchk.org.hk/Useful_information.aspx. Accessed 30 Sep 2018.

23. Singapore Clinical Research Institute.

About PAROS. Available from:

https://www.scri.edu.sg/crn/pan-asian-resuscitation-outcomes-study-paros-clinical-research-network-crn/about-paros/.

Accessed 30 Sep 2018.

24. Gräsner JT, Herlitz J, Koster RW,

Rosell-Ortiz F, Stamatakis L, Bossaert L. Quality management in

resuscitation—towards a European Cardiac Arrest Registry (EuReCa).

Resuscitation 2011;82:989-94. Crossref

25. Cardiac Arrest Registry to Enhance

Survival. myCARES. net. Available from: https://mycares.net. Accessed 30

Sep 2018.

26. Xie WC, Chan MH, Mak KC, Chan WT, He

M. Trends in the incidence of 15 common cancers in Hong Kong, 1983-2008.

Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2012;13:3911-6. Crossref

27. Leung CB, Cheung WL, Li PK. Renal

registry in Hong Kong—the first 20 years. Kidney Int Suppl (2011)

2015;5:33-8. Crossref