© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

MEDICAL PRACTICE CME

Consensus statements on diagnosis and management

of chronic idiopathic constipation in adults in Hong Kong

Justin CY Wu, MB, ChB, MD1; Annie OO

Chan, MB, ChB, PhD2; TK Cheung, MB, BS, PhD3;

Ambrose CP Kwan, MB, BS3; Vincent KS Leung, MB, BS4;

WC Sze, MB, BS, GradDFM3; Victoria PY Tan, MB, BS5

1 Department of Medicine and

Therapeutics, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong

2 Department of Gastroenterology and

Hepatology, Hong Kong Sanatorium & Hospital, Happy Valley, Hong Kong

3 Private Practice, Hong Kong

4 Department of Gastroenterology and

Hepatology, Hong Kong Baptist Hospital, Kowloon Tong, Hong Kong

5 Department of Medicine, The University

of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Prof Justin CY Wu (justinwu@cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Objective: The estimated

prevalence of chronic idiopathic constipation in Hong Kong is 14%. An

expert panel of local gastroenterologists has created a set of consensus

statements with the aim of providing localised guidance on the diagnosis

and management of this common condition by primary care physicians.

Participants: An expert panel

consisting of seven local gastroenterologists convened in August 2018 in

Hong Kong.

Evidence: Published primary

research articles, meta-analyses, and guidelines and consensus

statements issued by different regional and international societies on

the diagnosis and management of chronic idiopathic constipation were

reviewed.

Consensus process: Draft

consensus statements were prepared prior to the meeting. The consensus

statements were finalised during the meeting with contributions from the

panel members based on their collective knowledge and clinical

experience.

Conclusions: A total of 11

consensus statements were created, including five concerning patient

assessment and diagnosis, two relating to non-pharmacological

management, and four on pharmacological management. These consensus

statements are intended to provide guidance to local general

practitioners and primary care physicians on managing patients with

chronic constipation in daily clinical practice.

Introduction

Chronic idiopathic constipation (CIC), also known

as functional constipation, is a common gastrointestinal disorder with an

estimated prevalence of 14% in the Hong Kong general population.1 Constipation is often perceived as a decrease in

frequency of bowel movements, but normal bowel function can range anywhere

from 3 times daily to 3 times weekly, and fewer than 50% of people

experience the conventional norm of once-daily bowel motion.2 In addition to infrequent bowel movements, patients

with chronic constipation also complain of straining, hard stools,

abdominal discomfort, and feelings of incomplete evacuation.3 In the primary care setting, the Rome IV criteria may

guide diagnosis of CIC, along with simple laboratory tests and physical

examination to rule out secondary causes.4

5

Management of CIC typically begins with

non-pharmacological measures including exercise and increased dietary

fibre and fluid intake. When these general measures have failed to relieve

constipation, therapies, such as bulking agents, osmotic laxatives,

stimulant laxatives, and stool softeners are used to promote regular bowel

movements. Newer pharmacological therapies include prokinetic agents (5-HT4

agonists) that promote gut motility and prosecretory agents (guanylate

cyclase C agonists) that increase intestinal secretion. In Hong Kong,

patients also seek Chinese herbal medicine and acupuncture for relief of

constipation.

Current management practices for CIC in Hong Kong

largely follow Western guidelines and principles. Given that there are

cultural differences among patients and physicians regarding symptom

perception, treatment practices, and goals, there is a need for localised

CIC management guidelines. Hence, these consensus statements were

developed with the aim of providing guidance to local primary care

physicians on diagnosis and management of CIC.

Methods

An expert panel consisting of seven local

gastroenterologists convened on 9 August 2018 in Hong Kong. Published

primary research articles, meta-analyses, and guidelines and consensus

statements issued by different regional and international societies on CIC

diagnosis and management were reviewed, and draft consensus statements

were prepared prior to the meeting. These statements were divided into

three sections: patient assessment and diagnosis, non-pharmacological

management, and pharmacological management. The consensus statements were

finalised during the meeting with contributions from the panel members

based on their collective knowledge and clinical experience.

Results

Patient assessment and diagnosis

Statement 1: Primary care doctors are the major care

providers for diagnosis and management of chronic idiopathic constipation

The Rome IV diagnostic criteria for CIC can be too

complex and impractical for daily use in the primary care setting.

Adopting a pragmatic approach that combines these symptom criteria with

other elements, such as a visual guide (Bristol Stool Scale) and quality

of life impairment, may enhance diagnosis of constipation and evaluation

of its severity. Higher vigilance about the patient’s regular use of

natural products or health supplements to promote bowel function is also

important, as it is often overlooked.

Patients with symptoms that are refractory to

second-line treatment should be referred for specialist assessment.

Failure to fulfil diagnostic criteria should not preclude referral to a

gastroenterologist, especially in patients with complications or

bothersome symptoms that affect their quality of life. Patients with

alarming features, such as anaemia, recent onset of symptoms after 50

years of their absence, rectal bleeding, significant weight loss, abnormal

physical examination, and family history of colon cancer should also be

referred for further assessment.4 5 6

Psychiatric co-morbidities are not uncommon in patients with chronic

constipation, and any feature of significant psychiatric co-morbidities

should prompt referral to a psychiatrist.7

Statement 2: Routine extensive diagnostic and

physiological testing is not recommended for chronic constipation

Thorough history taking pertaining to age,

symptomology, acuteness of symptoms, and medication history is important

to exclude various causes of constipation.5

8 Preliminary laboratory

investigations consisting of complete blood count, serum calcium, glucose

levels, and thyroid function tests are generally adequate to screen for

underlying metabolic or other organic pathology.5

8 9

Careful abdominal and digital rectal examinations are also important in

the primary care setting. A rectal exam can reveal rectal tumours,

haemorrhoids, impacted faeces, anal sphincter tone, presence of mucus, and

stool colour.5 8 9 Abdominal

X-ray is a simple, non-invasive investigation that may show faecal

impaction. These investigations have to be individualised according to

patient expectations and preferences.

Advanced diagnostic procedures, such as barium

enema, defaecography, colonic transit studies, magnetic resonance imaging,

manometry, and balloon expulsion test should be reserved for patients with

suspected slow transit constipation and defaecatory disorder in the

specialist care setting.

Statement 3: Differential diagnoses of chronic

idiopathic constipation include secondary causes of constipation, such as

medications, electrolyte imbalances, structural abnormalities and

metabolic (eg, hypothyroidism, hypercalcaemia, diabetes mellitus) or

pathological (eg, Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis) disorders.

Alarming features suggestive of a serious gastrointestinal disorder should

prompt referral to a gastroenterologist or surgeon

Constipation is a common adverse reaction to many

medications (notably opioids, diuretics, antidepressants, antihistamines,

antispasmodics, anticonvulsants, aluminium antacids, and iron

supplements), and constipation may necessitate their discontinuation, if

appropriate.8 10 Intake of herbal supplements and traditional Chinese

medicines should also be considered as potential causes.

Any recent onset of constipation with alarming

symptoms should prompt the need for exclusion of colorectal cancer.

Although there is no evidence for an association between chronic

constipation and increased colorectal cancer risk, colon cancer screening

may be warranted in individuals >50 years with recent onset

constipation and/or other alarming features.5

11

Statement 4: The revised Rome IV criteria are useful

for diagnosing chronic idiopathic constipation but can be cumbersome to

use in clinical practice

The Rome IV criteria define CIC as the presence of

two or more of the following5:

Loose stools should rarely be present without the

use of laxatives, and there should be insufficient criteria for irritable

bowel syndrome. These criteria need to be fulfilled for the last 3 months

with symptom onset at least 6 months prior to diagnosis.

It is important to recognise that there is a

significant overlap between CIC and constipation-predominant irritable

bowel syndrome. Both conditions exist on a continuous spectrum, but the

latter is distinguished by the presence of abdominal pain.5 Patients with CIC may periodically encounter symptoms

of constipation related to irritable bowel syndrome.

The long duration required after symptom onset is a

major limitation of the Rome IV criteria. Instead, cases with recurrent

presentation to the clinic with consistent symptoms should be considered

for diagnosis of CIC. The chronic constipation diagnostic tool proposed by

the Asian Neurogastroenterology and Motility Association, which requires a

duration of only 3 months after symptom onset for diagnosis, has been

demonstrated as a useful alternative to the Rome III criteria in Asian

patients.12

The Bristol Stool Scale is a useful guide for

facilitating communication with patients, although it may not include the

subset of patients who present with difficulty passing stool but do not

have type 1 or 2 stool consistency. Patients should also be encouraged to

keep a stool diary and record their bowel habits to facilitate accurate

diagnosis.4 10

Statement 5: Chronic constipation can be classified as

normal-transit, slow-transit, or defaecatory disorder

This pathophysiological classification categorises

constipation according to colonic transit time and additional functional

or anatomical disruption that leads to obstructed defaecation. It is made

with the aid of advanced tests performed by gastroenterologists but should

not significantly affect first-line management in the primary care

setting. These pathophysiological mechanisms may co-exist and contribute

to treatment refractoriness in some patients. In each of these categories,

there may be underlying secondary causes that need careful evaluation. For

example, slow transit constipation can be a gastrointestinal manifestation

commonly seen in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Slow transit

constipation is strongly associated with irritable bowel syndrome.

Anorectal structural pathology, such as rectocele, may contribute to

defaecatory disorder.

Rectal hyposensitivity has been proposed as a

mechanism associated with constipation, but it is generally believed to be

a consequence of CIC, resulting from chronic rectal distension, rather

than a cause.13

Non-pharmacological management

Statement 6: Dietary and lifestyle adjustments,

including a high-fibre diet, adequate hydration, and physical activity,

should be made before starting pharmacological treatment. Patients with

pelvic floor dysfunction should be referred for physiotherapy

In recent years, the Hong Kong Chinese diet has

become increasingly low in dietary fibre. The dietary fibre intake of the

Hong Kong Chinese population is estimated to be only 10 to 12 g/day—barely

half of that seen in Western societies (about 20 g/day).14 Although some patients may benefit from a fibre-rich

diet, there are currently no data showing that increasing dietary fibre

will help to relieve constipation.8

15 Furthermore, excessive fibre

intake may actually worsen symptoms in severely constipated patients.15 Particularly, elderly patients and those with

inadequate fluid intake or on diuretics may be at risk.8 Hence, a high-fibre diet should be accompanied by

adequate hydration to avoid symptoms of faecal impaction. Consumption of

fruits high in soluble fibre, including papayas and kiwis, can be

recommended to patients.

Dysbiosis has been associated with constipation in

some studies. However, there is insufficient evidence to recommend

probiotics as an effective remedy for CIC.8

10 16

Developing good toilet habits can be beneficial.

Patients should be encouraged to schedule routine bathroom time

(postprandial, when urge may be higher) and use simple manoeuvres, such as

elevating the feet with a footstool.5

Prolonged sitting (>10 minutes) on the toilet is not recommended.

Statement 7: Data on the use of traditional Chinese

medicine in the management of chronic idiopathic constipation are

conflicting

A 16-week randomised double-blind clinical trial

conducted in Hong Kong on 291 patients with CIC showed that the hemp

seed-containing Chinese herbal formula, MaZiRenWan, was significantly more

effective than placebo at increasing the number of complete spontaneous

bowel movements (CSBMs; P<0.005 at week 8 and week 16) but not more

effective than the stimulant laxative senna (P=0.14 at week 8).17 18 19 Patients should be asked about their use of Chinese

medicine, as is commonly used for constipation. It may substantiate the

effectiveness of the treatment or contribute to adverse effects.

Pharmacological management

Statement 8: Pharmacological management should be

considered if lifestyle and dietary measures do not provide adequate

relief of chronic idiopathic constipation. First-line pharmacological

treatments recommended in primary care include bulking agents, osmotic

laxatives, and stool softeners. Combination therapy with agents across

different classes/mechanisms can be considered before moving to

second-line therapy

Commonly used bulk-forming agents include soluble

fibre, such as psyllium, methylcellulose, and polycarbophil and insoluble

fibre, such as wheat bran. A meta-analysis of three randomised controlled

trials involving 293 patients with CIC showed that soluble fibre

supplementation increases stool frequency (relative risk [RR]=0.25; 95%

confidence interval [CI]=0.16-0.37).16

Long-term use of bulking agents, especially insoluble fibre, is

discouraged because of their propensity to cause bloating and discomfort.16 Caution should be exercised when

giving bulk-forming agents to patients already on a high-fibre diet, as

this may worsen faecal impaction.

Electrolyte-free polyethylene glycol (PEG) and

lactulose are commonly recommended osmotic laxatives in CIC. A

meta-analysis of 10 randomised controlled trials concluded that PEG was

superior to lactulose in outcomes of stool frequency, consistency, and

relief of abdominal pain.19 In

general, PEG is also better tolerated (less likely to cause bloating and

gas) than lactulose, which may result in better compliance by patients.6 Given the favourable efficacy and

safety profile, long-term use of PEG is acceptable as a first-line

treatment for CIC.8 The use of

phosphate solution is strongly discouraged because of the high potential

for serious complications, including phosphate nephropathy and electrolyte

imbalances, especially in elderly people.5

20 21

The panel does not recommend the stool softener docusate as a primary

treatment for CIC given that it was shown to be inferior to psyllium at

improving stool frequency in a randomised controlled trial involving 170

patients with CIC.22

Patients require adequate counselling on regular,

consistent use of medications, regardless of clinical status after dose

titration, to prevent the development of severe refractory symptoms.

Treatment goals should be realistic. Various

outcome measures and definitions of treatment response have been reported

in clinical trials on constipation. In general, achieving one additional

spontaneous bowel movement per week from baseline is recommended as an

indicator of initial positive response. Patients should be counselled that

the normal bowel frequency is a minimum of 3 times per week rather than

once daily. In addition to achieving the desired bowel frequency, a

successful treatment response should also encompass improvement in quality

of life and prevention of complications.

Treatment failure can be considered after 2 months

(alongside non-pharmacological measures) before proceeding to second-line

therapy.6 This period is also

dependent on patient preference.

Statement 9: Linaclotide can be considered as

second-line treatment for chronic idiopathic constipation. Diarrhoea may

be an adverse effect in some patients, and patients should be educated

about this possibility before initiating therapy. Careful vigilance for

severe diarrhoea is recommended before long-term regular use

Second-line pharmacotherapeutic options for CIC

include prokinetic agents (prucalopride) and prosecretory agents

(lubiprostone, linaclotide, plecanatide).6

23 Both linaclotide and

lubiprostone have shown high-quality evidence of efficacy and safety for

treatment of CIC.16 Currently,

linaclotide (290 μg) is the only agent in this category that is registered

for use in Hong Kong. Because the general recommended daily dose of

linaclotide for CIC is 145 μg, once-every-2-days dosing of the 290-μg

capsule is recommended to minimise diarrhoea and improve tolerability.5 6

Four randomised clinical trials involving 651

patients demonstrated that lubiprostone was superior to placebo for

treatment of CIC (RR=0.67; 95% CI=0.58-0.77).16

Diarrhoea and nausea occurred significantly more frequently with

lubiprostone.16

The efficacy and safety of linaclotide were

evaluated in two 12-week randomised double-blind placebo-controlled

dual-dose (145 μg and 290 μg) trials involving 1276 patients with chronic

constipation. In both trials, a significantly higher proportion of

patients receiving linaclotide achieved the primary endpoint (≥3 CSBMs per

week and an increase of ≥1 CSBMs from baseline during at least 9 of the 12

weeks) compared with those receiving placebo (P<0.01 for all

comparisons).24 In addition,

linaclotide significantly improved stool frequency and consistency,

reduced straining, and reduced abdominal symptoms (bloating and

discomfort). A meta-analysis that combined these two trials and a previous

phase II dose-ranging trial conducted in 310 patients with CIC reported

that 79% of those receiving linaclotide failed to respond to therapy, as

compared with 94.9% of placebo-treated patients (RR=0.84; 95%

CI=0.80-0.87), and diarrhoea was more common with linaclotide treatment

(RR=3.08; 95% CI=1.27-7.48).25 In

a subsequent phase IIIb trial conducted in 483 patients with chronic

constipation and significant abdominal bloating, linaclotide significantly

improved bowel symptoms and bloating compared with placebo.26

Two large randomised placebo-controlled trials

(n=2731) have recently demonstrated the efficacy of plecanatide (3-mg and

6-mg doses) at improving CIC.27 28 Both trials reported a significant

improvement in the proportion of durable CSBM responders and a small

incidence of diarrhoea.27 28

Because prosecretory agents induce active secretion

of electrolytes and fluids into the intestinal lumen, monitoring baseline

renal function is advisable in selected patients who are at risk of

dehydration or renal dysfunction.23

The Food and Drug Administration has classified linaclotide as a pregnancy

category C drug.29

Statement 10: Stimulant laxatives should be regarded as

rescue therapy for chronic idiopathic constipation, not as first-line

agents, and used only on an as-needed basis (less than daily). Regular

chronic use of stimulant laxatives is discouraged. Long-term use of

glycerine suppositories and/or water enemas is acceptable

Stimulant laxatives increase intestinal motility

and intestinal secretion. Commonly used stimulant laxatives include

Agiolax, senna (Senokot), and bisacodyl (Dulcolax). Frequent use of these

agents may lead to long-term dependency or abuse, and therefore, general

practitioners or specialists should counsel patients on limiting their

use.30 The concern that stimulant

laxatives may cause permanent damage to the autonomic nervous system of

the colon has not been proven.15

Statement 11: Surgery should only be used as a last

resort for slow-transit constipation or to treat identified disorders that

require surgical correction. Exclusion of defaecatory disorder and whole

gut slow transit problems is important

Defaecatory disorder commonly coexists with slow-

or normal-transit constipation.31

This is a common cause that contributes to poor laxative treatment

response. These patients must be properly assessed by gastroenterologists

with expertise in management of functional bowel disorder before being

recommended for surgery.

Surgery is generally not effective for management

of refractory CIC and is associated with significant morbidity.10 Rare conditions like megacolon may be an indication

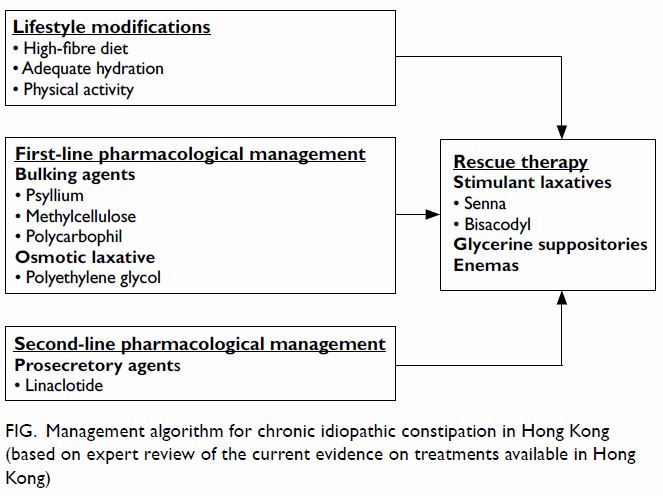

for surgery. The proposed management algorithm for CIC is summarised in

the Figure.

Figure. Management algorithm for chronic idiopathic constipation in Hong Kong (based on expert review of the current evidence on treatments available in Hong Kong)

Conclusions

Chronic constipation is a common gastrointestinal

disorder in patients presenting to primary care providers. These consensus

statements give a general overview of diagnostic and treatment approaches

to CIC appropriate for primary care physicians in Hong Kong.

Diagnosis of CIC is made using the revised Rome IV

criteria, along with simple laboratory tests and physical examinations,

which are important for excluding secondary causes, such as medications,

electrolyte imbalances, structural abnormalities, and metabolic or

pathological disorders.5 8 Patients presenting with alarming features should be

referred to gastroenterologists or surgeons for appropriate further

assessments.

Dietary and lifestyle adjustments should be

attempted first before initiating pharmacological treatments for CIC.

Soluble fibre supplementation may improve stool frequency, but excessive

use of bulking agents (especially insoluble fibre) may lead to bloating

and faecal impaction. Among osmotic agents, PEG is more effective and

better tolerated than lactulose.6 19

Linaclotide may be considered as second-line

therapy for patients who have failed fibre and osmotic laxatives.6 It is the only prosecretory agent currently registered

for use in Hong Kong. Linaclotide has been demonstrated to generate

significant improvements of constipation symptoms in CIC compared with

placebo, but diarrhoea is a significant concern, especially with the

higher dose that is normally used (290 μg). Lubiprostone, linaclotide, and

plecanatide are all superior to placebo for treatment of CIC, but no

head-to-head trials comparing these medications have been conducted thus

far.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the concept, acquisition

of data, interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, and critical

revision for important intellectual content. All authors had full access

to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for

publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of

interest.

Funding/support

English language editing and writing support,

funded by an unrestricted educational grant from AstraZeneca Hong Kong

Limited, was provided by Cassandra Thomson and Shirani Kanaganayagam of

MIMS (Hong Kong) Limited.

References

1. Cheng C, Chan AO, Hui WM, Lam SK. Coping

strategies, illness perception, anxiety and depression of patients with

idiopathic constipation: a population-based study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther

2003;18:319-26. Crossref

2. Heaton KW, Radvan J, Cripps H, Mountford

RA, Braddon FE, Hughes AO. Defecation frequency and timing, and stool form

in the general population: a prospective study. Gut 1992;33:818-24. Crossref

3. Johanson JF, Kralstein J. Chronic

constipation: a survey of the patient perspective. Aliment Pharmacol Ther

2007;25:599-608. Crossref

4. Rao SS, Meduri K. What is necessary to

diagnose constipation. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2011;25:127-40. Crossref

5. Lacy BE, Mearin F, Chang L, et al. Bowel

disorders. Gastroenterology 2016;150:1393-407. Crossref

6. Tse Y, Armstrong D, Andrews CN, et al.

Treatment algorithm for chronic idiopathic constipation and

constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome derived from a Canadian

national survey and needs assessment on choices of therapeutic agents. Can

J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;2017:8612189. Crossref

7. Nehra V, Bruce BK, Rath-Harvey DM,

Pemberton JH, Camilleri M. Psychological disorders in patients with

evacuation disorders and constipation in a tertiary practice. Am J

Gastroenterol 2000;95:1755-8.

8. Shin JE, Jung HK, Lee TH, et al.

Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic functional

constipation in Korea, 2015 revised edition. J Neurogastroenterol Motil

2016;22:383-411. Crossref

9. Lembo A, Camilleri M. Chronic

constipation. N Engl J Med 2003;349:1360-8. Crossref

10. Sobrado CW, Neto IJ, Pinto RA, Sobrado

LF, Nahas SC, Cecconello I. Diagnosis and treatment of constipation: a

clinical update based on the Rome IV criteria. J Coloproctol

2018;38:137-44. Crossref

11. Power AM, Talley NJ, Ford AC.

Association between constipation and colorectal cancer: systematic review

and meta-analysis of observational studies. Am J Gastroenterol

2013;108:894-903.

12. Gwee KA, Bergmans P, Kim J, et al.

Assessment of the Asian Neurogastroenterology and Motility Association

chronic constipation criteria: An Asian multicenter cross-sectional study.

J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2017;23:262-72. Crossref

13. Whitehead WE, Bharucha AE. Diagnosis

and treatment of pelvic floor disorders: what’s new and what to do.

Gastroenterology 2010;138:1231-5. Crossref

14. Zhang R, Wang Z, Fei Y, et al. The

difference in nutrient intakes between Chinese and Mediterranean, Japanese

and American diets. Nutrients 2015;7:4661-88. Crossref

15. Müller-Lissner SA, Kamm MA,

Scarpignato C, Wald A. Myths and misconceptions about chronic

constipation. Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100;232-42.

16. Ford AC, Moayyedi P, Lacy BE, et al.

American College of Gastroenterology monograph on the management of

irritable bowel syndrome and chronic idiopathic constipation. Am J

Gastroenterol 2014;109 Suppl 1:S2-26. Crossref

17. Wang X, Yin J. Complementary and

alternative therapies for chronic constipation. Evid Based Complement

Alternat Med 2015;2015:396396. Crossref

18. Zhong LL, Cheng CW, Kun W, et al.

Efficacy of MaZiRenWan, a Chinese herbal medicine, in patients with

functional constipation in a randomized controlled trial. Clin

Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018 Apr 12. Epub ahead of print. Crossref

19. Cheng CW, Bian ZX, Zhu LX, Wu JC, Sung

JJ. Efficacy of a Chinese herbal proprietary medicine (Hemp Seed Pill) for

functional constipation. Am J Gastroenterol 2011;106:120-9. Crossref

20. Lee-Robichaud H, Thomas K, Morgan J,

Nelson RL. Cochrane review: lactulose versus polyethylene glycol for

chronic constipation. Evidence-Based Child Health 2011;6:824-64. Crossref

21. Zheng S, Yao J. Expert consensus on

the assessment and treatment of chronic constipation in the elderly. Aging

Med 2018;1:8-17. Crossref

22. Abcar A, Hever A, Momi JS, Sim JJ.

Acute phosphate nephropathy. Perm J 2009;13:48-50. Crossref

23. Lembo AJ, Schneier HA, Shiff SJ, et

al. Two randomized trials of linaclotide for chronic constipation. N Engl

J Med 2011;365:527-36. Crossref

24. McRorie JW, Daggy BP, Morel JG,

Diersing PS, Miner PB, Robinson M. Psyllium is superior to docusate sodium

for treatment of chronic constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther

1998;12:491-7. Crossref

25. Jiang C, Xu Q, Wen X, Sun H. Current

developments in pharmacological therapeutics for chronic constipation.

Acta Pharm Sin B 2015;5:300-9. Crossref

26. Ford AC, Suares NC. Effect of

laxatives and pharmacological therapies in chronic idiopathic

constipation: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut 2011;60:209-18. Crossref

27. Lacy BE, Schey R, Shiff SJ, et al.

Linaclotide in chronic idiopathic constipation patients with moderate to

severe abdominal bloating: a randomized, controlled trial. PLoS One

2015;10:e0134349. Crossref

28. Miner PB Jr, Koltun WD, Wiener GJ, et

al. A randomized phase III clinical trial of plecanatide, a uroguanylin

analog, in patients with chronic idiopathic constipation. Am J

Gastroenterol 2017;112:613-21. Crossref

29. Linzess (linaclotide capsules):

highlights of prescribing information. Available from:

https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2012/202811s000lbl.pdf.

Accessed 19 Mar 2019.

30. Thomas RH, Allmond K. Linaclotide

(Linzess) for irritable bowel syndrome with constipation and for chronic

idiopathic constipation. P T 2013;38:154-60.

31. Roerig JL, Steffen KJ, Mitchell JE,

Zunker C. Laxative abuse: epidemiology, diagnosis and management. Drugs

2010;70:1487-503. Crossref