© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

REMINISCENCE: ARTEFACTS FROM THE HONG KONG MUSEUM OF

MEDICAL SCIENCES

Triturator for smallpox vaccine production

Harry YJ Wu, MD, DPhil

Medical Ethics and Humanities Unit, Li Ka Shing

Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

The triturator that was used to produce smallpox

and rabies vaccines was donated by the Hong Kong Government Department of

Health in 1995. This decommissioned device witnessed an important moment

in the history of disease prevention in Hong Kong. According to the World

Health Organization, there have been no smallpox cases in Hong Kong since

1952. Hong Kong was further certified disease free in 1979, 2 years before

the worldwide eradication. Despite this, the story that the machine tells

is an unfinished one, owing to perpetual speculation about whether Hong

Kong would have been able to prevent contagious diseases on its own.

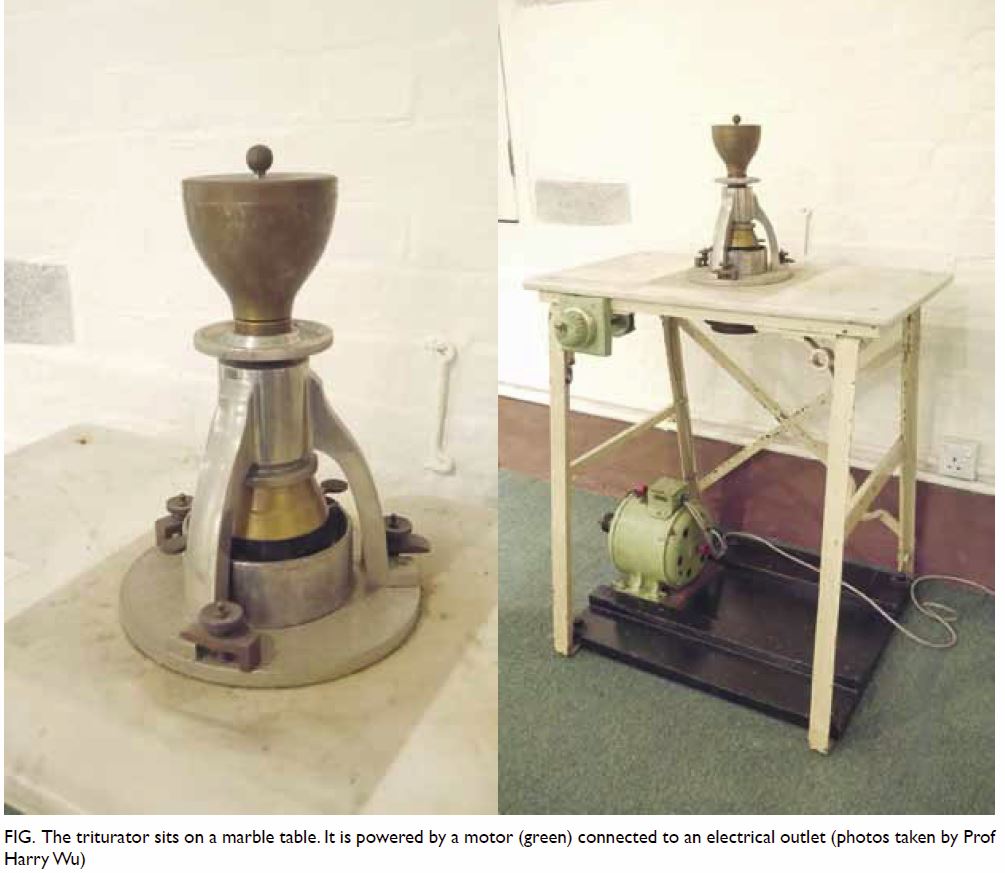

The triturator, measuring 32 cm tall and 21.5 cm in

diameter, was produced in Lausanne, Switzerland. It was used in the

processing of Semple-type vaccines, such as for smallpox and rabies

vaccine between 1940 and 1982. Usually, lymph pulp of calves was fed into

the machine with glycerine through the conical copper funnel on the top.

The tissue then passed through the central copper grinding spindle before

the emulsion was collected via a key in two lower crescent-shaped

stainless steel cups. The grinder was powered by an electric motor under

the marble table (Fig). To prevent contamination, the equipment was

protected with a wood-framed glass hood. In general, calves were the most

commonly used animals for producing smallpox vaccine. In Hong Kong,

buffalo calves were originally kept in the Animal House of the

Bacteriological Institute, before the house was demolished to become Caine

Lane Garden.

Figure. The triturator sits on a marble table. It is powered by a motor (green) connected to an electrical outlet (photos taken by Prof Harry Wu)

In Hong Kong’s medical history, credentials are

given to a number of individuals regarding the development of smallpox

vaccination technology, for example, Alexander Pearson, a surgeon working

for the East India Company in the early 19th century, who practised

vaccination in Macao; Pearson’s student, Yao Hochun, known as A-Hequa by

Westerners, who published a book on vaccination in 1817; and William James

Woodman, Medical Officer of Health, who scaled up the vaccination

campaigns among Chinese through Tung Wah Hospital and the Chinese Public

Dispensaries in 1916.1 Smallpox

vaccination could not have been successful without these important

figures. However, history tells us how disease onset, development, and

control were contingent upon factors beyond the individual sagas of these

heroes.

Smallpox had been a common disease among Chinese.

It mostly affected young children and people who did not have strong

immune systems. It is documented that in the Ming and Qing

dynasties in China, measures were taken to survey the disease and avoid

infection.2 More precisely, around

the 16th or 17th centuries, inoculation techniques had already been

developed for prevention. Methods, such as insufflating powdered smallpox

crusts, stuffing a cotton pledget impregnated with smallpox scabs into the

nostrils of a child or making a child wear a patient’s unwashed

undergarment for 2 to 3 days, were common. However, when the first

Government Bacteriologist, William Hunter, arrived in Hong Kong, he

considered that such practices, famously known as ‘variolation’, were a

culprit for spreading disease. He also believed that the annual recurrence

of epidemic smallpox would continue in Hong Kong unless China finally

recognised the importance of providing the means for general vaccination

and re-vaccination.3 Such

accusations of Chinese antipathy towards Western vaccination measures

continued throughout various outbreaks.4

In the early days, compliance with public health measures could not have

been smoothed without the support of well-organised neighbourhood

organisations (kaifong) and public health educators from Chinese

Public Dispensaries.1

Between 1858 and 1952—the respective dates of the

first and the last reports of smallpox cases in Hong Kong—vaccination was

just one of many measures taken to deal with the endemics resulting from a

variety of social conditions. The effective control and exacerbation of

infectious diseases were both attributed to Hong Kong’s unique geographic

environment. For example, as a peninsula connecting Canton, commercial

travelling was common between the inland and the port, accelerating the

spread of diseases. As an archipelago, smallpox patients had, for a long

period of time, been isolated in the jail on Stonecutters Island. And as a

growing financial and transport hub, Hong Kong had to digest innumerable

travellers en route from rural southern China to Southeast Asia, or across

the Pacific to the United States, at the risk of becoming a

‘redistributive depot’ of diseases.5

In 1938, Tung Wah Smallpox Hospital, which was established in 1908 in

Kennedy Town, was no longer able to accommodate the surging numbers of

smallpox victims caused by refugees fleeing the Sino-Japanese War. The

shutdown of connections between Hong Kong and the important surrounding

ports in the Straits Settlements,6

Amoy,7 and Formosa,8 became one of the inevitable measures for preventing a

foreseeable pandemic.

The vaccine institute in Hong Kong was established

under Governor Des Voeux’s rule in 1891 before it was incorporated into

the Bacteriological Institute in 1906. Within 20 years, the Institute was

already able to produce vaccines against typhoid, paratyphoid, cholera and

meningococcal antiserum.1 During

wartime, Hong Kong had to seek help from the League of Nations for the

supply of smallpox vaccines.9

Products had to arrive by airmail to Hong Kong, passing airports where

quarantines were not implemented to ensure the quality and potency of

vaccines. For example, in February 1938, as reported in the Hong Kong

Telegraph, a shipment of vaccine left Bandung on a KLM plane and was

transhipped to Imperial Airways at Bangkok before arriving in Hong Kong.2 In addition to importation, local

vaccine production and vaccination became more extensive with lymph

obtained locally. Hong Kong even delivered vaccine to naval and military

authorities for the use in neighbouring ports.10

The rise, fall, and eventual disappearance of

smallpox and other contagious diseases in Hong Kong attest to the

complexity of disease prevention. Owing to the drastic decline in smallpox

cases in Hong Kong, the Pathological Institute (the original

Bacteriological Institute) ceased smallpox vaccine production in 1973.11 However, using the smallpox vaccine as an example, we

can see how a simple technological object functioned and how its nature

manifested in a complex society. In 1923, the Vaccination Ordinance

required that ‘any person, who in his opinion [of the Medical Officer of

Health] has been subjected to the risk of infection from smallpox, should

be vaccinated or re-vaccinated’.12

Now, the vaccination policy has become one that emphasises the citizen’s

own health insights and risk-bearing capacity. From an antipathic society

to a hub receiving Chinese medical tourists for various types of

vaccination, Hong Kong is now facing other problems that accompany novel

types of immigration, a more complicated cultural and societal

composition, and growing tension between necessary population flow and the

protection of its own citizens.

References

1. Chan-Yeung MM. A Medical History of Hong

Kong: 1842-1941. Hong Kong: Chinese University of Hong Kong Press; 2017.

2. Hsiung PJ. Ill or Well: Diseases and

Health of Young Children in Late Imperial China. Taipei: Lien-ching; 1999.

3. Hunter W. Report of the Government

Bacteriologist, for the year 1902. Hong Kong: Government Public Mortuary;

1903.

4. New Cases of Smallpox Vaccine Flow Here

by Daedalus. The Hong Kong Telegraph. 2 Feb 1938.

5. Peckham R. Epidemics in Modern Asia.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2016. Crossref

6. Hong Kong declared an infected port by

the Government of Straits Settlements. Hong Kong Government Gazette 1939

(Supplement), No 7, 6 Jan 1939.

7. Hong Kong declared an infected port by

Amoy. Hong Kong Government Gazette 1938 (Supplement), No 31, 4 Feb 1938.

8. Hong Kong declared an infected port by

the Government of Formosa. Hong Kong Government Gazette 1938 (Supplement),

No 48, 18 Feb 1938.

9. 4,000,000 Smallpox Vaccine Doses. Hong

Kong Sunday Herald. 18 Dec 1938.

10. Wong S. The calf vaccinating table.

Hong Kong Med J 2017;23:101-3.

11. The Bacteriological Institute and its

contributions to Hong Kong. In: Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences

Society. Plague, SARS and the Story of Medicine in Hong Kong. Hong Kong:

Hong Kong University Press; 2006:147-224.

12. Legislative Council, Draft Bill: An

Ordinance to consolidate and amend the law relating to Vaccination. Hong

Kong Government Gazette; 1922:176.