© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Management of thigh lipofibromatosis in a newborn: a

case report

YL Lam, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Orthopaedic Surgery)1;

WY Ho, MB, BS, FHKAM (Orthopaedic Surgery)1; Raymond Yau, MB,

BS, FHKAM (Orthopaedic Surgery)1; Victor WK Lee, MB, BS2;

Tony WH Shek, MB, BS, FHKAM (Pathology)2

1 Department of Orthopaedics and

Traumatology, Queen Mary Hospital, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

2 Department of Pathology, Queen Mary

Hospital, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr YL Lam (albertlam2000@yahoo.com)

Case report

A 3.6 kg (gravida 2 para 2 full-term normal vaginal

delivery) baby boy presented to Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong in

September 2015 with a painless swelling on the left thigh on day 2 after

birth. The antenatal check-up had been normal. Physical examination

revealed a 2- × 2-cm intramuscular swelling over the lateral aspect of the

left thigh. There was mild tenderness but no increase in local

temperature, skin change, or thrill. Limb movements were normal and

symmetrical. Distal pulse and tissue circulation were also normal. Further

systemic examination revealed no syndromal features, other swelling, or

other significant findings on other systems.

Blood tests revealed slightly deranged white cell

count and haemoglobin, creatine kinase, lactate dehydrogenase, and

C-reactive protein levels. Renal and liver function tests and

calcium and phosphate levels were normal. Radiographs did not show any

abnormality. Ultrasonographic study on day 2 after birth revealed a

swollen and oedematous distal part of the left vastus lateralis muscle.

The muscular architecture was preserved. There was no definite mass and

the vascular signal was also normal. A repeat ultrasonographic study in

week 2 after birth showed an ill-defined intramuscular echogenic lesion at

the distal left vastus lateralis muscle. A magnetic resonance imaging scan

at age 2 months showed an infiltrative lesion of 3 × 4 × 4.3 cm in the

vastus lateralis muscle with extension to the short head of the biceps

muscle. It was heterogeneously hyperintense to the muscle on both T1- and

T2-weighted images.

An image-guided wide-bore needle biopsy revealed a

benign-looking lesion composed of fascicles of spindle cells admixed with

lobules of mature fat. The differential diagnoses included

lipofibromatosis, fibrous hamartoma of infancy, or less likely, calcifying

aponeurotic fibroma, and lipoblastoma or lipoblastomatosis.

During the course of the investigation, there was

deterioration of knee range in extension. At age 5 months, the flexion

contracture was 25 degrees. Clinically, there was size progression. In

addition, the parents were concerned about the subjective increase in

tumour size. After discussion of the treatment options with the parents, a

marginal excision was performed at age 5 months.

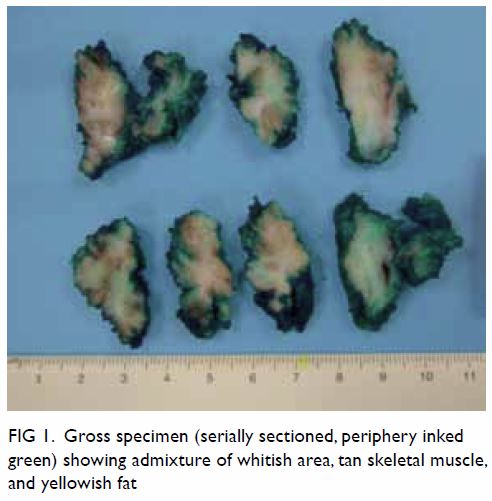

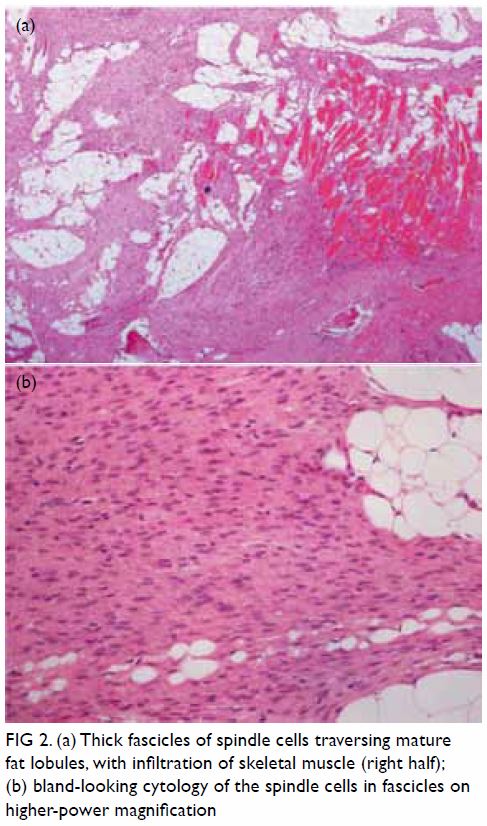

Microscopic examination of the surgical specimen

showed thick fascicles of bland-looking spindle cells traversing a large

number of mature adipocytic lobules, concentrated around the septal region

(Figs 1 and 2). Infiltration around the skeletal muscle was

noted. There was no organoid nest of mesenchymal cells to suggest fibrous

hamartoma of infancy, nor any calcification foci to suggest calcifying

aponeurotic fibroma. Mitosis was inconspicuous. Necrosis was absent.

Immunohistochemical staining of the spindle cells showed CD34+, S100+, and

actin patchy+, whereas beta-catenin, epithelial membrane antigen, desmin,

and c-kit were negative. A diagnosis of lipofibromatosis was made.

Figure 1. Gross specimen (serially sectioned, periphery inked green) showing admixture of whitish area, tan skeletal muscle, and yellowish fat

Figure 2. (a) Thick fascicles of spindle cells traversing mature fat lobules, with infiltration of skeletal muscle (right half); (b) bland-looking cytology of the spindle cells in fascicles on higher-power magnification

The patient was given postoperative physiotherapy

as maintenance for his knee range of motion. The latest follow-up was at 5

months postoperatively (age 10 months). He was able to pull himself to a

standing position. He could walk with support for more than 10 steps.

Thickened scarring could be felt under the old incision wound. His latest

knee range was 0 to 130 degrees (the same as the right side).

Discussion

The reported occurrence of neonatal tumours is one

in 12 500 to 27 500 live births although there is little information on

the real incidence. It has not been well studied because of its rarity.1 Soft tissue tumours account for

25% of all neoplasms in infancy, of which approximately 15% are malignant.2

It is quite impossible to clinically differentiate

between a benign and a malignant tumour in a child. Further investigation

by means of ultrasonography or magnetic resonance imaging may provide a

definitive diagnosis in certain conditions such as haemangioma but may be

impossible without histological studies.1

More confusing, the behaviour of the tumour in this

specific patient group may not be the same as in their adult counterparts.

The natural history of some disease entities has not been documented. Even

a benign lesion may invade locally, causing symptoms such as developmental

deformity and even death.1

Watchful neglect may be a treatment option for some

lesions with a potential of spontaneous regression such as haemangioma.2 In the other conditions, surgical

resection may be an option for management of a progressing disease.

There are four possible diagnoses based on the

first wide-bore needle biopsy finding. Calcifying aponeurotic fibroma3 is tumour characterised by foci of calcification,

palisaded round cells and radiating arms of fibroblasts. This lesion has a

high tendency of local recurrence (50%). The natural history is tumour

growth reduction with age. Conservative resection or palliative resection

should be considered.

Lipoblastoma or the diffuse subtype

lipoblastomatosis3 is a benign

tumour and resembles fetal fat tissue. The solitary lipoblastoma is

usually in the subcutaneous area and lipoblastomatosis may invade deep

structures. Local recurrence may occur in 9% to 22% of patients especially

in the diffuse subtype.

Fibrous hamartoma of infancy3 is a benign infiltrative lesion. It is a rapidly

growing mass in the subcutaneous or dermis of the axillary fold, shoulder,

arm, forearm, back, groin or thigh. It is characterised by well-defined

fibrocollagenous tissue, small rounded primitive mesenchymal cells, and

mature fat. Local excision is the treatment of choice. Recurrence is rare.

Lipofibromatosis,3

also known as non-desmoid-type infantile fibromatosis, is a very rare

paediatric disease. To date, approximately only 60 cases have been

reported. Typically, it is an ill-defined slow-growing tumour that

presents as a painless lesion in the limbs. The rate of local recurrence

is high. The regrowth and persistent disease rate is 72%.4 Fortunately, there is no known metastasis.

These four diagnoses differ quite significantly in

prognosis and recommended management. In the present case, we advised

conservative resection for histology, prognosis, management of disease

progression, and treatment of the knee flexion contracture.

The diagnosis of a tumour in the neonatal period

causes significant psychological distress to parents.5 Understanding the natural history and prognosis is the

first step towards alleviating parental anxiety followed by inviting them

to participate in the planning of future management. Sincere communication

is an essential part of patient management. Sometimes professional

intervention in the form of psychological support should also be

considered.

Author contributions

All authors had full access to the data,

contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and

take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Concept or design: YL Lam, WY Ho, R Yau, TWH Shek.

Acquisition of data: YL Lam, VWK Lee, TWH Shek.

Analysis or interpretation of data: YL Lam, VWK Lee, TWH Shek.

Drafting of the manuscript: YL Lam, TWH Shek.

Critical revision for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: YL Lam, VWK Lee, TWH Shek.

Analysis or interpretation of data: YL Lam, VWK Lee, TWH Shek.

Drafting of the manuscript: YL Lam, TWH Shek.

Critical revision for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acknowledgement

We thank Ms Carol Anne Higgins for proofreading the

manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of

interest.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any

funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the institutional review

board (Ref. UW15/414).

References

1. Moore SW, Satgé D, Sasco AJ, Zimmermann

A, Plaschkes J. The epidemiology of neonatal tumours, report of

international working group. Pediatr Surg Int 2003;19:509-19. Crossref

2. Palumbo JS, Zwerdling T. Soft tissue

sarcomas of infancy. Semin Perinatol 1999;23:299-309. Crossref

3. Fletcher CD, Bridge JA, Hogendoorn PC,

Mertens F. WHO Classification of Tumours. Lyon: IARC; 2013.

4. Fetsch JF, Miettinen M, Laskin WB,

Michal M, Enzinger FM. A clinicopathological study of 45 pediatric soft

tissue tumors with an admixture of adipose tissue and fibroblastic

elements, and a proposal for classification as lipofibromatosis. Am J Surg

Pathol 2000;24:1491-500. Crossref

5. Orbach D, Sarnacki S, Brisse HJ, et al.

Neonatal cancer. Lancet Oncol 2013;14:e609-20. Crossref