Hong

Kong Med J 2019 Feb;25(1):58–63 | Epub 31 Jan 2019

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

MEDICAL PRACTICE CME

Antibiotic management of acute pharyngitis in primary

care

The Advisory Group on Antibiotic Stewardship

Programme in Primary Care

Angus MW Chan, MB, ChB (Glasg), FHKAM (Family

Medicine)1; Winnie WY Au, MB, BS2; David VK Chao,

FRCGP, FHKAM (Family Medicine)3; K Choi, MB, BS, FHKAM (Family

Medicine)4; KW Choi, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Medicine)5;

Sarah MY Choi, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Community Medicine)6; Y Chow,

MB, BS, FHKAM (Psychiatry)7; Cecilia YM Fan, MB, BS, FHKAM

(Family Medicine)8; PL Ho, MD, FACP9; Eric MT Hui,

FHKCFP, FHKAM (Family Medicine)10; KH Kwong, MB, BS, MFM (Clin)

(Monash)11; Benjamin YS Kwong, BSc Pharm, MPharmS12;

TP Lam, MD, FHKAM (Family Medicine)13; Edman TK Lam, MB, ChB,

FHKAM (Pathology)14; KW Lau, BSc Pharm, MPharmS14;

Leo Lui, MB, BS, FHKAM (Pathology)14; Ken HL Ng, MB, BS, FHKAM

(Pathology)14; Martin CS Wong, MD, FHKAM (Family Medicine)15;

TY Wong, MB, BS, FHKAM (Medicine)14; CF Yeung, MB, BS, FHKAM

(Paediatrics)16; Joyce HS You, PharmD, BCPS (AQ Infectious

Diseases)17; Raymond WH Yung, MB, BS, FHKAM (Pathology)18

1 Hong Kong College of Family

Physicians, Hong Kong

2 Infection Control Branch, Centre for

Health Protection, Department of Health, Hong Kong

3 Department of Family Medicine and

Primary Health Care, United Christian Hospital, Hospital Authority, Hong

Kong

4 Hong Kong Medical Association, Hong

Kong

5 Hong Kong Society for Infectious

Diseases, Hong Kong

6 Primary Care Office, Department of

Health, Hong Kong

7 Quality HealthCare Medical Services

Limited, Hong Kong

8 Professional Development and Quality

Assurance, Department of Health, Hong Kong

9 IMPACT Editorial Board, Reducing

bacterial resistance with IMPACT, 5th edition, Hong Kong

10 Department of Family Medicine, New

Territories East Cluster, Hospital Authority, Hong Kong

11 Human Health Holdings Limited, Hong

Kong

12 Chief Pharmacist’s Office, Hospital

Authority, Hong Kong

13 Department of Family Medicine and

Primary Care, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

14 Infection Control Branch, Centre for

Health Protection, Department of Health, Hong Kong

15 Hong Kong Academy of Medicine, Hong

Kong

16 Hong Kong Doctors Union, Hong Kong

17 School of Pharmacy, The Chinese

University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

18 Hong Kong Sanatorium & Hospital,

Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Edman TK Lam (edmanlam@cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

The Centre for Health Protection of the

Department of Health has convened the Advisory Group on Antibiotic

Stewardship Programme in Primary Care (the Advisory Group) to formulate

guidance notes and strategies for optimising judicious use of

antibiotics and enhancing the Antibiotic Stewardship Programme in

Primary Care. Acute pharyngitis is one of the most common conditions

among out-patients in primary care in Hong Kong. Practical

recommendations on the diagnosis and antibiotic treatment of acute

streptococcal pharyngitis are made by the Advisory Group based on the

best available clinical evidence, local prevalence of pathogens and

associated antibiotic susceptibility profiles, and common local

practice.

Introduction

The Government of the Hong Kong Special

Administrative Region attaches great importance to the threat of

antimicrobial resistance. Under the authority of the Food and Health

Bureau, and with collaborative efforts from stakeholders, the Hong Kong

Strategy and Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance (2017-2022) was

established in July 2017. Recommendations in six key areas and 19

objectives were included in this Action Plan, aiming to slow the emergence

of antimicrobial resistance and prevent its spread.

In connection with this Action Plan, the Centre for

Health Protection of the Department of Health convened the Advisory Group

on Antibiotic Stewardship Programme in Primary Care (the Advisory Group)

comprising key stakeholders in the public and private sectors, academia,

and major professional societies. Its objective is to formulate guidance

notes and strategies for optimising the judicious use of antibiotics and

enhancing the Antibiotic Stewardship Programme in Primary Care (https://www.chp.gov.hk/en/features/49811.html).

Guidance notes on antibiotic treatments for common infections seen by

primary care doctors have been developed based on the best available

clinical evidence, local prevalence of pathogens and associated antibiotic

susceptibility profiles, and local practice. Clinical evidence has mainly

referred to international practices, the latest guidelines from

international organisations, and systematic review articles. In addition,

simple information sheets for out-patients are prepared to raise awareness

and enable them to use antibiotics appropriately. Primary care doctors

play an important role in antimicrobial resistance containment measures by

not only practising rational antibiotic prescriptions but also educating

and engaging out-patients about the safe use of antibiotics during

clinical encounters.

Acute pharyngitis is the acute inflammation of the

oropharynx. It is characterised by sore throat and pharyngeal erythema. It

is one of the most common conditions among out-patients in primary care in

Hong Kong.1 2

Acute pharyngitis is usually a benign,

self-limiting illness with an average length of illness of 1 week. It is

often caused by respiratory viruses (eg, rhinovirus, coronavirus,

adenovirus, influenza virus, parainfluenza virus, respiratory syncytial

virus and metapneumovirus). The other viruses of concern are enterovirus,

herpes simplex virus, Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, and human

immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Viral pharyngitis is a condition for which

antibiotics are not necessary. Out-patients with a sore throat and

associated symptoms and signs, including conjunctivitis, coryza, cough,

discrete ulcerative stomatitis, hoarseness, diarrhoea, and viral

exanthema, are most likely to have a viral illness, such as common cold,

influenza, herpangina, and oral herpes.

Beta-haemolytic streptococci, particularly group A

Streptococcus (GAS), are the most common bacterial pathogens of

acute pharyngitis. Group A Streptococcus is estimated to be

responsible for approximately 10% of cases of acute pharyngitis in adults

and 15% to 30% of those in children.3

A local study at an accident and emergency department in Hong Kong showed

that for those presenting with a sore throat and without symptoms of

common cold or influenza, the prevalence rates of GAS pharyngitis were

2.65% in adults and adolescents aged >14 years and 38.6% in children

aged 3 to 14 years; none of the children aged <3 years had GAS

pharyngitis.4 Group A Streptococcus

pharyngitis can lead to suppurative (eg, quinsy, otitis media, and other

invasive infections) and non-suppurative (eg, acute rheumatic fever,

poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis) complications. However, acute

rheumatic fever has not been described as a complication of either group C

Streptococcus or group G Streptococcus pharyngitis.

Streptococcal pharyngitis is the most common form of acute pharyngitis, in

which antibiotic treatment is indicated.

Diagnosis of acute streptococcal pharyngitis

There are different recommendations on the

diagnostic strategy of acute streptococcal pharyngitis. Ideally, to obtain

a definitive diagnosis, out-patients with symptoms and signs suggestive of

a bacterial cause (eg, sudden onset of fever, anterior cervical

lymphadenopathy, tonsillopharyngeal exudates) should be tested for GAS

with a rapid antigen detection test (RADT) and/or throat culture.5 6 7 8 A negative

RADT should be backed up by a throat culture in children and adolescents,

but not in adults. Practically and clinically, different various clinical

scoring criteria have been developed to estimate the likelihood of acute

streptococcal pharyngitis, and we recommend that practitioners make

clinical decisions about laboratory testing and/or antibiotic prescribing.9 10

11 The FeverPAIN score was

developed in the primary care setting in the United Kingdom in 2013.12 The Centor criteria were developed in the emergency

department setting in the United States in 1981; the modified Centor

criteria add age to the original Centor criteria.13

14 The FeverPAIN score criteria

are Fever (during the previous 24 hours), Purulence (pus on tonsils),

Attend rapidly (within 3 days after onset of symptoms), severely Inflamed

tonsils, and No cough or coryza; each of the criteria is worth 1 point

(maximum score of 5). A score of 0 or 1 is associated with a 13% to 18%

likelihood of isolating Streptococcus. A score of 2 or 3 is

associated with a 34% to 40% likelihood of isolating Streptococcus.

A score of 4 or 5 is associated with a 62% to 65% likelihood of isolating

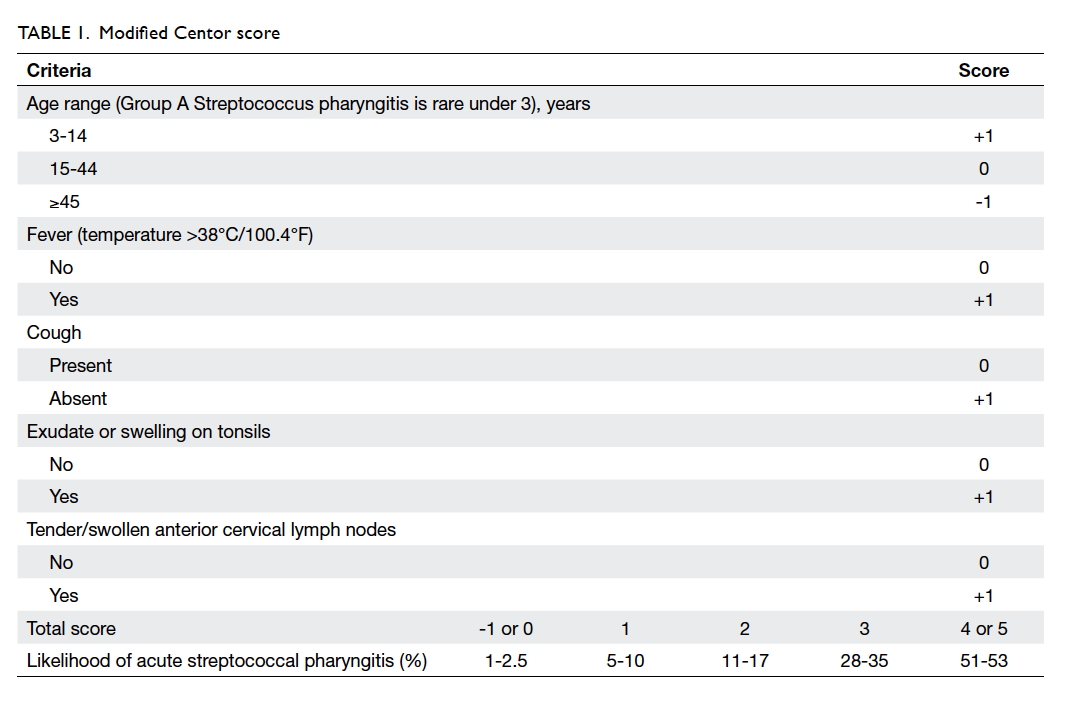

Streptococcus. In contrast, the modified Centor criteria are age 3

to 14 years, history of fever (over 38°C), absence of cough, exudate or

swelling on tonsils, and tender/swollen anterior cervical lymph nodes;

each of the criteria is worth 1 point (maximum score of 5); note that 0

points are assigned for age 15 to 44 years, whereas -1 point is given for

age ≥45 years. A score of -1, 0 or 1 is associated with a 1% to 10%

likelihood of isolating Streptococcus. A score of 2 or 3 is

associated with an 11% to 35% likelihood of isolating Streptococcus.

A score of 4 or 5 is associated with a 51% to 53% likelihood of isolating

Streptococcus. There is currently uncertainty about which clinical

scoring tool is more effective.

Based on the clinical experience that RADT is not

commonly available, and throat culture is time consuming, requiring a 2-

to 3-day turnaround time, the Advisory Group agreed that using clinical

scoring criteria is preferential to not using any laboratory tests or

clinical scoring criteria, and the modified Centor criteria are more

widely and easily used (Table 1).

Antibiotic treatment of acute streptococcal pharyngitis

Although the symptoms of acute streptococcal

pharyngitis resolve without antibiotic treatment, there are arguments that

justify antibiotic treatment for acute symptom relief, prevention of

suppurative and non-suppurative complications, and reduction of

communicability. A recent systematic review on antibiotics for sore throat

found that the clinical benefits were modest and required treatment of

many with antibiotics for one to benefit (the number of people with sore

throat who must be treated to resolve the symptoms of one by day 3 was

about 3.7 for those with positive throat swabs for Streptococcus;

6.5 for those with a negative swab, and 14.4 for those in whom no swab had

been taken).15 Antibiotic

treatment may shorten the duration of sore throat by 1 to 2 days.

Antibiotics may prevent complications of GAS infection, including acute

rheumatic fever or suppurative complications.15

Out-patients are considered no longer contagious after 24 hours of

antibiotic treatment. However, little evidence supports the prevention of

poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis by antibiotic treatment.15

Although scarlet fever occurs throughout the year,

there has been a seasonal pattern in Hong Kong, with higher activity

observed from May to June and from November to March in the past few

years.16 Scarlet fever is a

bacterial infection caused by GAS, and it classically presents with fever,

sore throat, red and swollen tongue (known as strawberry tongue), and

erythematous rash with a sandpaper texture. It is mainly a clinical

diagnosis and can be treated by appropriate antibiotics effectively.

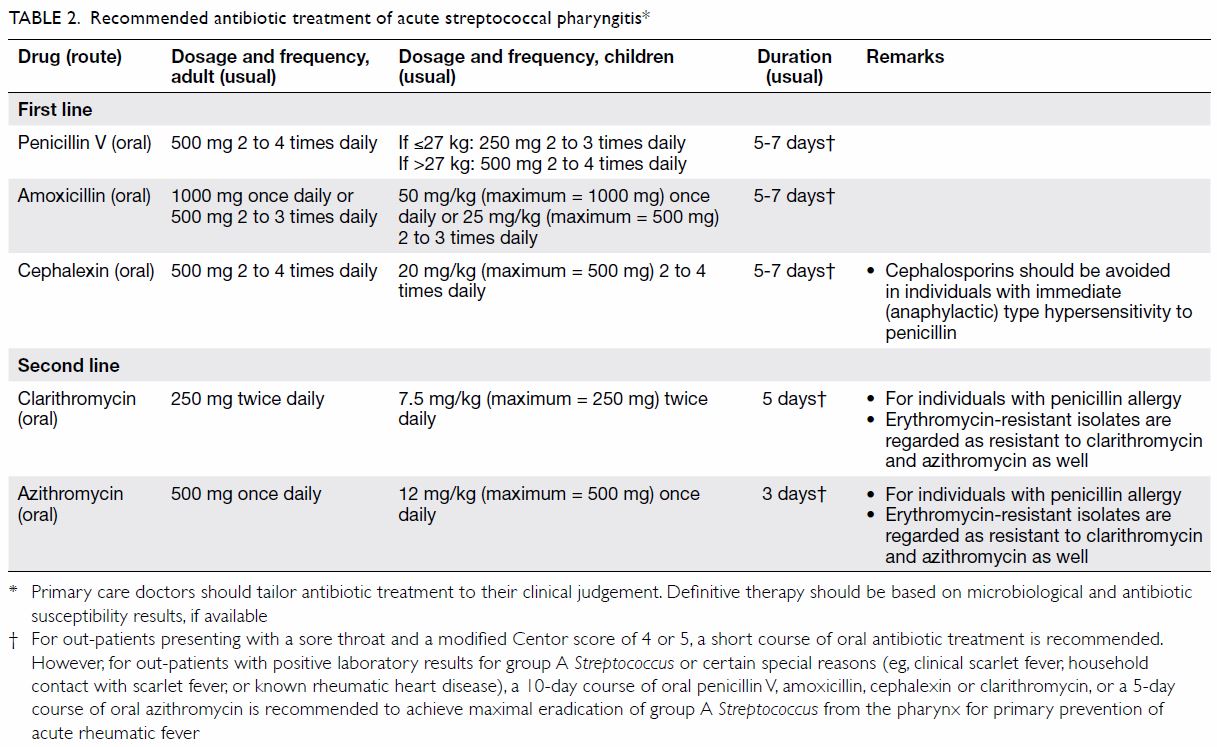

After considering the benefits and risks (eg,

allergies and side-effects) of antibiotic treatment, the Advisory Group

agreed that antibiotic treatment is indicated for out-patients presenting

with a sore throat and a modified Centor score of 4 or 5 and for

out-patients with positive laboratory results or certain special reasons

(eg, clinical scarlet fever, household contact with scarlet fever, or

known rheumatic heart disease) [Table 2].

Oral penicillin V or amoxicillin are the

recommended antibiotics of choice for out-patients who are not allergic to

these agents. Resistance of GAS to penicillins and other beta-lactams has

not been reported.17

First-generation cephalosporins (eg, oral cephalexin) are the first-line

agents for out-patients with penicillin allergies who are not

anaphylactically allergic. Other cephalosporins (eg, oral cefaclor,

cefuroxime) are alternatives, but they are not favoured as the first-line

agents because of their broad spectrum of activity. Resistance of GAS to

macrolides (eg, oral azithromycin, clarithromycin, erythromycin) is known

to be common in Hong Kong. Erythromycin-resistant isolates of GAS are

regarded as resistant to clarithromycin and azithromycin as well.17 According to data from the Microbiology Division of

the Public Health Laboratory Services Branch of the Centre for Health

Protection, which undertakes bacterial isolation and antibiotic

susceptibility testing in public and private out-patient settings in Hong

Kong, the erythromycin resistance rates of beta-haemolytic streptococci

(in which GAS contributed to majority of them) in throat swab specimens

has risen to 59.1% in the last few years.18

Studies have shown that the erythromycin resistance rates of GAS isolates

were 4% in the United States, 3.2% in France, 32.8% in Spain, and 65% in

Taiwan.19 20 21 22 Respiratory fluoroquinolones (eg, oral levofloxacin)

are active against GAS, but they have an unnecessarily broad spectrum of

activity and are not recommended for routine treatment of acute

streptococcal pharyngitis.6

Excessive use of respiratory fluoroquinolones may lead to delay in the

diagnosis of tuberculosis and increased fluoroquinolone resistance among Mycobacterium

tuberculosis in Hong Kong.23

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole should not be used because it does not

eradicate GAS from out-patients with acute pharyngitis.6

After considering the basic principle that

narrow-spectrum antibiotics should be used as the first-line agents to

treat an infection that is not life-threatening, the Advisory Group agreed

that oral penicillin V, amoxicillin or cephalexin are the first-line

agents to treat acute streptococcal pharyngitis (Table 2). Treatment with oral macrolides or

respiratory fluoroquinolones requires sound justifications, including

documented history of beta-lactam allergy or intolerance, positive throat

culture results, and associated antibiotic susceptibility profiles.

A 10-day course of oral penicillin V, amoxicillin,

cephalexin or clarithromycin, or a 5-day course of oral azithromycin is

recommended by the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the American

College of Physicians, and the American Academy of Pediatrics to achieve

maximal eradication of GAS from the pharynx for primary prevention of

acute rheumatic fever.6 7 8 However, a

recent systematic review comparing a 3- to 6-day course of oral

antibiotics (primarily cephalosporins) with a conventional 10-day course

of oral penicillin found similar effectiveness in children, but no

conclusions could be drawn on the complication rates of acute rheumatic

fever and poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis.24

Furthermore, a 5-day course of antibiotic treatment is sufficient to

mitigate the clinical course of group C Streptococcus and group G

Streptococcus pharyngitis, as acute rheumatic fever is not a

complication of infections due to these organisms.8

Based on the clinical experience that the

prevalence of acute rheumatic fever is very low in Hong Kong nowadays, the

Advisory Group agreed that a 5- to 7-day course of oral penicillin V,

amoxicillin or cephalexin, or a 5-day course of oral clarithromycin, or a

3-day course of oral azithromycin is sufficient to treat out-patients

presenting with a sore throat and a modified Centor score of 4 or 5.

However, for out-patients with positive laboratory results for GAS or

certain special reasons (eg, clinical scarlet fever, household contact

with scarlet fever, or known rheumatic heart disease), a 10-day course of

oral penicillin V, amoxicillin, cephalexin or clarithromycin, or a 5-day

course of oral azithromycin is recommended to achieve maximal eradication

of GAS from the pharynx for primary prevention of acute rheumatic fever (Table 2).

Other issues

Alternative diagnosis should be considered for

out-patients who present with unusually severe signs and symptoms, such as

difficulty swallowing, drooling, neck tenderness or swelling, or systemic

unwellness. They should be evaluated for potentially dangerous infections

(eg, peritonsillar abscess, retro-/para-pharyngeal abscess, acute

epiglottitis and systemic infections). Out-patients who do not improve

within 5 to 7 days or who have worsening symptoms should be evaluated for

a previously unsuspected diagnosis (eg, infectious mononucleosis, primary

HIV infection, or gonococcal pharyngitis). Infectious mononucleosis is a

clinical syndrome characterised by fever, severe pharyngitis (which lasts

longer than GAS pharyngitis), cervical or diffuse lymphadenopathy, and

prominent constitutional symptoms. Out-patients who have infectious

mononucleosis and are treated with amoxicillin may develop a generalised,

erythematous, maculopapular rash, and this should not be regarded as a

penicillin allergy. A properly taken sexual history may hint at

possibility of sexually transmitted infections like HIV and gonorrhoea.

Management of out-patients with infections should

be individualised. Primary care doctors should check, document, and inform

out-patients well about antibiotic treatment (eg, indications,

side-effects, allergies, contra-indications, potential drug-drug

interactions). Out-patients should take antibiotics exactly as prescribed

by their doctors. If their symptoms change, persist, or get worse, they

should seek medical advice promptly.

Primary care doctors are invited to show their

commitment on judicious use of antibiotics by visiting the “I Pledge”

website (https://www.chp.gov.hk/en/static/100755.html) and signing a certificate on

pledging to use antibiotics responsibly. Furthermore, this invitation is

open to general public. Primary care doctors can engage their out-patients

on “I Pledge” during clinical encounters to facilitate shared decision

making on antibiotic prescribing.

Conclusion

Acute pharyngitis is one of the most common

conditions among out-patients in primary care in Hong Kong. Practical

recommendations on the diagnosis and antibiotic treatment of acute

streptococcal pharyngitis are made in consultation with key stakeholders

in primary care settings such that the recommendations can be tailored to

their needs. The recommendations are under regular review, in

consideration of the latest research, together with local prevalence of

pathogens and associated antibiotics susceptibility profiles, and common

local practice.

Author contributions

All authors have made substantial contributions to

the viewpoints of this study, literature review, and critical revision for

important intellectual content. ETK Lam was responsible for literature

search and drafting of the manuscript. All authors had full access to the

data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for

publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

As editors of this journal, DVK Chao and MCS Wong

were not involved in the peer review process of this article. All other

authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Declaration

An earlier version of this article was published

online in the Centre for Health Protection website, November 2017

(https://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/guidance_notes_acute_pharynitis_full.pdf).

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any

funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

1. Lam TP, Ho PL, Lam KF, Choi K, Yung R.

Use of antibiotics by primary care doctors in Hong Kong. Asia Pac Fam Med

2009;8:5. Crossref

2. Kung K, Wong CK, Wong SY, et al. Patient

presentation and physician management of upper respiratory tract

infections: a retrospective review of over 5 million primary clinic

consultations in Hong Kong. BMC Fam Pract 2014;15:95. Crossref

3. Alcaide ML, Bisno AL. Pharyngitis and

epiglottitis. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2007;21:449-69. Crossref

4. Wong MC, Chung CH. Group A streptococcal

infection in patients presenting with a sore throat at an accident and

emergency department: prospective observational study. Hong Kong Med J

2002;8:92-8.

5. Chan JY, Yau F, Cheng F, Chan D, Chan B,

Kwan M. Practice recommendation for the management of acute pharyngitis.

Hong Kong J Paediatr 2015;20:156-62.

6. Shulman ST, Bisno AL, Clegg HW, et al.

Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of group A

streptococcal pharyngitis: 2012 update by the Infectious Diseases Society

of America. Clin Infect Dis 2012;55:e86-102. Crossref

7. Harris AM, Hicks LA, Qaseem A; High

Value Care Task Force of the American College of Physicians and for the

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Appropriate antibiotic use for

acute respiratory tract infection in adults: advice for high-value care

from the American College of Physicians and the Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention. Ann Intern Med 2016;164:425-34. Crossref

8. Gerber MA, Baltimore RS, Eaton CB, et

al. Prevention of rheumatic fever and diagnosis and treatment of acute

streptococcal pharyngitis: a scientific statement from the American Heart

Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease Committee

of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, the

Interdisciplinary Council on Functional Genomics and Translational

Biology, and the Interdisciplinary Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes

Research: endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics. Circulation

2009;119:1541-51. Crossref

9. ESCMID Sore Throat Guideline Group,

Pelucchi C, Grigoryan L, et al. Guideline for the management of acute sore

throat. Clin Microbiol Infect 2012;18(Suppl 1):1-28. Crossref

10. Public Health England, UK Government.

Management and treatment of common infections. Antibiotic guidance for

primary care: For consultation and local adaptation. 2017. Available from:

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/managing-common-infections-guidance-for-primary-care.

Accessed 6 Oct 2017.

11. The National Institute for Health and

Care Excellence, Public Health England, UK Government. Sore throat

(acute): antimicrobial prescribing. 2018. Available from:

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng84. Accessed 13 Jul 2018.

12. Little P, Moore M, Hobbs FD, et al.

PRImary care Streptococcal Management (PRISM) study: identifying clinical

variables associated with Lancefield group A β-haemolytic Streptococci and

Lancefield non–Group A streptococcal throat infections from two cohorts of

patients presenting with an acute sore throat. BMJ Open 2013;3:e003943. Crossref

13. Centor RM, Witherspoon JM, Dalton HP,

Brody CE, Link K. The diagnosis of strep throat in adults in the emergency

room. Med Decis Making 1981;1:239-46. Crossref

14. McIsaac WJ, White D, Tannenbaum D, Low

DE. A clinical score to reduce unnecessary antibiotic use in patients with

sore throat. CMAJ 1998;158:75-83.

15. Spinks A, Glasziou PP, Del Mar CB.

Antibiotics for sore throat. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

2013;(11):CD000023. Crossref

16. Centre for Health Protection,

Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR Government. Letter to doctors: further

increase in scarlet fever activity in Hong Kong. 2017. Available from:

https://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/letters_to_doctors_20171204.pdf. Accessed

13 Jul 2018.

17. Clinical and Laboratory Standards

Institute. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

27th ed. 2017. Available from:

https://clsi.org/media/1469/m100s27_sample.pdf. Accessed 6 Oct 2017.

18. Centre for Health Protection,

Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR Government. Bacterial pathogen

isolation and percentage of antimicrobial resistance—out-patient setting.

2014-2018. Available from

http://www.chp.gov.hk/en/data/1/10/641/697/3345.html. Accessed 13 Jul

2018.

19. Tanz RR, Shulman ST, Shortridge VD, et

al. Community-based surveillance in the United States of

macrolide-resistant pediatric pharyngeal group A Streptococci during 3

respiratory disease seasons. Clin Infect Dis 2004;39:1794- 801. Crossref

20. d’Humières C, Cohen R, Levy C, et al.

Decline in macrolide-resistant Streptococcus pyogenes isolates

from French children. Int J Med Microbiol 2012;302:300-3. Crossref

21. Rubio-López V, Valdezate S, Alvarez D,

et al. Molecular epidemiology, antimicrobial susceptibilities and

resistance mechanisms of Streptococcus pyogenes isolates resistant

to erythromycin and tetracycline in Spain (1994-2006). BMC Microbiol

2012;12:215. Crossref

22. Chuang PK, Wang SM, Lin HC, et al. The

trend of macrolide resistance and emm types of group A Streptococci from

children at a medical center in southern Taiwan. J Microbiol Immunol

Infect 2015;48:160-7. Crossref

23. Ho PL, Wu TC, Chao DV, et al, editors.

Reducing bacterial resistance with IMPACT—Interhospital Multi-disciplinary

Programme on Antimicrobial ChemoTherapy. 5th version. 2017. Available

from:

https://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/reducing_bacterial_resistance_with_impact.pdf.

Accessed 6 Oct 2017.

24. Altamimi S, Khalil A, Khalaiwi KA,

Milner RA, Pusic MV, Al Othman MA. Short-term late-generation antibiotics

versus longer term penicillin for acute streptococcal pharyngitis in

children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;(8):CD004872. Crossref