DOI: 10.12809/hkmj176236

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Cystic artery pseudoaneurysm with haemobilia after

laparoscopic cholecystectomy

K To, BA (Hons); Eric CH Lai, MB, ChB, MRCSEd,

FRACS; Daniel TM Chung, MB, ChB, MRCSEd, FRCS; Oliver CY Chan, MB ChB,

MRCSEd, FRCS; CN Tang, MB, BS, FRCS

Department of Surgery, Pamela Youde Nethersole

Eastern Hospital, Chai Wan, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Eric CH Lai (elaichun@gmail.com)

Case presentation

A 56-year-old man underwent laparoscopic

cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis at another hospital in December

2013. The cholecystectomy was uneventful and the patient was discharged

home 3 days later. However, after hospital discharge, the patient

presented with recurring upper abdominal pain, tarry stool, and fever. He

was admitted to another hospital 4 weeks after the cholecystectomy because

of fever, right upper quadrant pain, and haematemesis. Emergency

oesophagogastroduodenoscopy and colonoscopy were performed. No bleeding

source was identified. Computed tomography (CT) revealed subhepatic fluid

collection; old-blood–stained fluid was drained by image-guided catheter

drainage. The patient was transferred to the Department of Surgery, Pamela

Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Hong Kong, for further treatment.

When the patient arrived at hospital, his blood

pressure was approximately 90/60 mm Hg and his pulse rate was 110 beats

per minute. Laboratory studies revealed the following values: haemoglobin

level, 72 g/L; white blood cell count, 20.3 × 109 /L; platelet

count, 388 × 109 /L; total bilirubin, 164 μmol/L; alanine

aminotransferase, 187 IU/L; and alkaline phosphatase, 337 IU/L. The

patient was treated with intravenous fluid hydration and was transfused

with three units of packed red blood cells. He was also given a course of

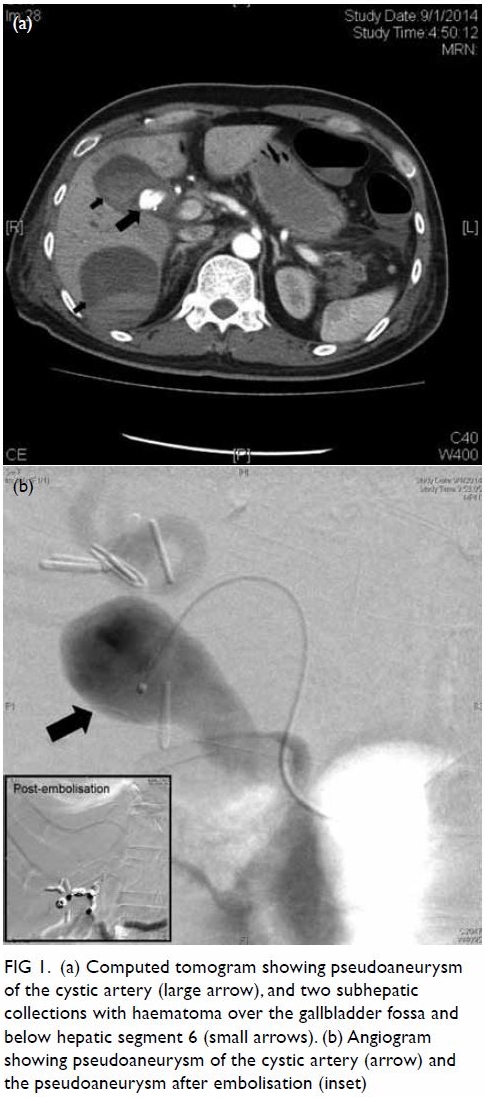

antibiotics. Abdominal CT showed a cystic artery pseudoaneurysm of 1.22 ×

1.96 × 1.38 cm (anterior-posterior × transverse × longitudinal

dimensions). Two subhepatic collections with haematoma were also visible,

over the gallbladder fossa and below hepatic segment 6. Selective right

hepatic artery angiography revealed a pseudoaneurysm at the cystic artery.

This aneurysm was embolised with stainless steel coils (Fig

1). The catheter for subhepatic collection drainage was then

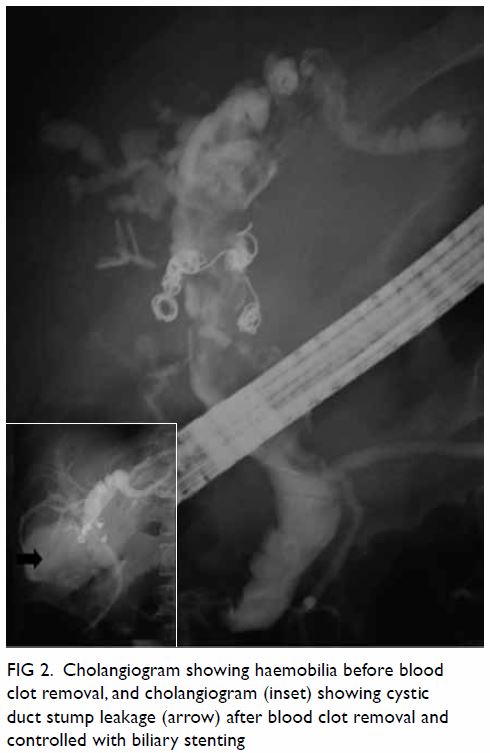

replaced with one with better positioning. Endoscopic retrograde

cholangiopancreatography was performed the next day. The cholangiogram

showed a dilated biliary tree with haemobilia; most of the blood clots

were extracted using a balloon. A cystic duct stump leak was observed

after blood clot removal, and a 10-cm-long 11.5-F biliary stent was

inserted for biliary drainage (Fig 2). Liver function improved gradually. The

patient was discharged from hospital 2 weeks after admission.

Figure 1. (a) Computed tomogram showing pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery (large arrow), and two subhepatic collections with haematoma over the gallbladder fossa and below hepatic segment 6 (small arrows). (b) Angiogram showing pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery (arrow) and the pseudoaneurysm after embolisation (inset)

Figure 2. Cholangiogram showing haemobilia before blood clot removal, and cholangiogram (inset) showing cystic duct stump leakage (arrow) after blood clot removal and controlled with biliary stenting

Follow-up CT no longer showed pseudoaneurysm and

instead showed a resolving collection. Endoscopic retrograde

cholangiopancreatography with stent removal was performed 3 months later.

The cholangiogram showed a normal biliary tree. The patient recovered and

liver function test results were normal.

Discussion

Hepatic artery or cystic artery pseudoaneurysms are

rare complications of laparoscopic cholecystectomy, with cystic artery

involvement being reported much less frequently in the literature.

Pseudoaneurysm formation is a consequence of vascular injury; important

causes include arterial access procedures, accident trauma, and surgical

trauma.1 Two-thirds of cases are

iatrogenic.1 With the advent of

laparoscopic cholecystectomy, iatrogenic hepatobiliary injury is now

another cause. Concomitant formation of cystic artery pseudoaneurysm and

cystic duct stump leak is a rare complication of laparoscopic

cholecystectomy. The majority of pseudoaneurysms present within 6 weeks

after the operation.2 3

We have reported a case of laparoscopic

cholecystectomy that was complicated by a cystic artery pseudo-aneurysm

and a cystic duct stump bile leak, which were managed with angiographic

coil embolisation and endoscopic biliary drainage, respectively. The

patient presented with the classic Quincke’s triad of haemobilia, namely

upper gastrointestinal bleeding, right upper quadrant pain, and

obstructive jaundice. The aetiology most likely originated from the

infected fluid collection after cholecystectomy, which caused a series of

events, including cystic duct stump leak, cystic artery pseudoaneurysm,

and haemobilia, in that order. First, bile leakage is a potential

complication of cholecystectomy and the cystic duct stump is the most

common site of leakage.4 The

contributing factor of cystic duct stump leak in the current case was

likely cystic duct stump necrosis secondary to mechanical or thermal

injury during cholecystectomy, as well as adjacent infection. Second,

haemobilia can occur secondary to a cystic artery pseudoaneurysm, although

extremely rarely. Artery pseudoaneurysm is a continuous inflammatory

process that leads to erosion in the elastic and muscular components of

the arterial wall, ultimately resulting in pseudoaneurysm formation. The

likely precipitating factors in the current case include initial clip

encroachment of the vasculature, mechanical or thermal injury, and

continuous inflammation due to the adjacent infected bile or collection.

Pseudoaneurysm can present with bleeding in the

form of haemobilia, haematemesis, or melaena. In the current case, upper

gastrointestinal bleeding from haemobilia resulted from the cystic artery

pseudoaneurysm’s communication with the cystic duct. The resulting

symptoms were typical of Quincke’s triad of upper abdominal pain, upper

gastrointestinal haemorrhage, and jaundice.5

However, these symptoms are present collectively only in a minority

(32%-40%) of patients.5 Thus,

detection relies heavily on both clinical reasoning and imaging

techniques. If intra-abdominal collection or haemorrhage is suspected

clinically, arterial-phase CT is appropriate to detect any pseudoaneurysm.

Since gastrointestinal haemorrhage is one of the presentations, urgent

oesophagogastroduodenoscopy may be arranged first to rule out any

suspected upper gastrointestinal pathology. However, as in the current

case, if that procedure fails to show any bleeding source, urgent CT

should be considered. Close observation and timely arrangement of

appropriate procedures are essential.

Prompt recognition with adequate management was

very important in the current case. The treatment of our patient included

five objectives: achieving haemostasis, controlling the cystic duct stump

leak, relieving obstructive jaundice, controlling the infection with

antibiotics, and draining the intra-abdominal collection. Untreated

haemobilia poses an immediate threat to life. It can lead to acute

haemodynamic instability, necessitating detection, access, and control of

the pseudoaneurysm. Arterial-phase CT is a good initial non-invasive mode

of detection of laparoscopic cholecystectomy complications. It can be used

to evaluate intra-abdominal collection, biliary tree dilatation, and

possible bile duct injury, and to visualise pseudoaneurysms or

haemorrhage. Arterial-phase CT also allows a three-dimensional assessment

of the bile duct and vasculature. Selective arterial angiography can

provide a real-time evaluation of pseudoaneurysms and bleeding. At the

same time, it can provide the chance of immediate therapeutic

intervention. Transarterial embolisation is the treatment of choice for

haemostasis, and a high success rate, of 75% to 100%, has been

reported.2 3 5 When bleeding control by embolisation fails, repeated

sessions of transarterial embolisation for haemostasis or surgical

intervention to repair or ligate the artery is necessary. Endoscopic

retrograde cholangiopancreatography with stent placement or sphincterotomy

is highly effective in diagnosing haemobilia, controlling cystic duct

stump leakage, and relieving obstructive jaundice. We favoured stenting

over sphincterotomy because of a presumed lower risk of immediate

complications.

The lessons to be learnt from this case include the

importance of (1) meticulous surgical techniques (such as good

haemostasis, careful use of powered devices, proper use of endoclips, and

adequate drainage of the operative field), and (2) early recognition and

prompt management.

In conclusion, cystic artery pseudoaneurysm is a

rare, potentially life-threatening complication of laparoscopic

cholecystectomy, and prompt recognition and treatment are essential.

Haemobilia may be present many weeks after the initial injury.

Declaration

The authors have no conflicts of interest to

disclose.

References

1. Green MH, Duell RM, Johnson CD, et al.

Haemobilia. Br J Surg 2001;88:773-86.

2. Senthilkumar MP, Battula N, Perera M, et

al. Management of a pseudo-aneurysm in the hepatic artery after a

laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2016;98:456-60. Crossref

3. Nicholson T, Travis S, Ettles D, et al.

Hepatic artery angiography and embolization for hemobilia following

laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 1999;22:20-4. Crossref

4. Lau WY, Lai EC, Lau SH. Management of

bile duct injury after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a review. ANZ J Surg

2010;80:75-81. Crossref

5. Merrell SW, Schneider PD.

Hemobilia—evolution of current diagnosis and treatment. West J Med

1991;155:621- 5.