Hong

Kong Med J 2017 Dec;23(6):653.e1–2

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj164952

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

PICTORIAL MEDICINE

Is it an orbital foreign body?

Mohamed Shaheeda, FRCSEd, MPH; Stacey C Lam, MB,

ChB; Noel CY Chan, FRCSEd, FCOphthHK; Hunter KL Yuen, FRCSEd, FCOphthHK

Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences,

The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Stacey C Lam (staceylam@gmail.com)

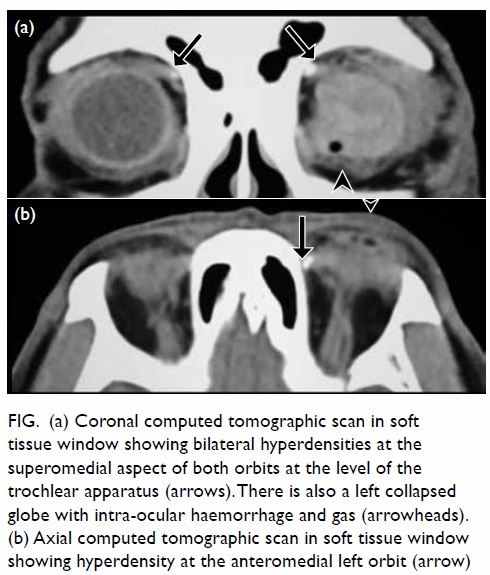

A 58-year-old man presented with left globe rupture

following blunt orbital trauma. Visual acuity was light perception only.

There was lid swelling, ecchymosis, and a deformed globe with scleral

laceration. Computed tomography (CT) of the orbit revealed a 3.7-mm

hyperdensity at the superomedial aspect of the left globe, interpreted by

the radiologist as a possible intra-orbital foreign body (Fig).

Figure. (a) Coronal computed tomographic scan in soft tissue window showing bilateral hyperdensities at the superomedial aspect of both orbits at the level of the trochlear apparatus (arrows). There is also a left collapsed globe with intra-ocular haemorrhage and gas (arrowheads). (b) Axial computed tomographic scan in soft tissue window showing hyperdensity at the anteromedial left orbit (arrow)

Thorough history for the mechanism of trauma,

physical examination for a wound site and thin cut CT sections were

reviewed. History revealed blunt orbital trauma by a metallic rod rather

than a sharp penetrating injury. No cutaneous entry site was evident.

Computed tomography revealed bilateral hyperdensities at the level of the

trochlea, more pronounced on the left than the right, with no metallic

streak artefacts. All of the above supported a diagnosis of trochlear

calcification rather than an intra-orbital foreign body, and the patient

subsequently underwent emergency repair of scleral laceration without

orbital exploration.

Discussion

The trochlea is a cartilaginous pulley at the

superomedial aspect of the orbit through which the superior oblique muscle

tendon passes freely. It has a synovium-lined space, and like other

synovial joints of the body, the trochlea can develop calcifications in

the cartilage, tendon, or within the bursa-like cleft.1 The reported prevalence of incidental trochlear

calcifications on CT is 3-16%, with over 50% being unilateral.2 3 No clear

cause has been identified, but prior studies have postulated degenerative,

inflammatory, metabolic or traumatic aetiologies.4

Since trochlear calcification is asymptomatic, most cases go unnoticed by

radiologists as well as ophthalmologists. In the presence of co-existing

orbital trauma, it can be misdiagnosed as an intraorbital foreign body.

Surgical exploration around the trochlear region may cause damage and

scarring leading to diplopia.

Differentiation of the two entities requires

history taking, physical examination, and proper imaging. A foreign body

is present in one in six cases of orbital trauma, with metallic objects

and glass being the most common.5 A

review of the history to determine mechanism of injury is useful but may

be unreliable. Examination of the skin and conjunctiva, particularly the

fornices, may help detect subtle penetrating injuries. Radiological

assessment includes plain films, ultrasound, CT, and magnetic resonance

imaging. Plain films are limited to detection of metallic foreign bodies,

and ultrasound has limited use because foreign bodies can be masked by

surrounding highly reflective structures such as bone. Computed tomography

is an excellent means to identify high-density objects such as metal or

glass, but not organic matter. Magnetic resonance imaging is

contra-indicated in metallic foreign bodies, but may be useful for organic

foreign matter. Features of trochlear calcification may include

symmetrical presentation and typical site at the trochlear apparatus. Its

morphology has been described as comma, dot, and inverted U shape.2 In contrast, orbital foreign bodies are often

unilateral with no specific size, shape, or location. Metallic foreign

bodies may also generate streak artefacts.

Orbital calcifications can be incidental or

pathological. It is important to recognise trochlear calcifications as

distinct from foreign bodies so as to avoid unnecessary surgical

exploration in the presence of orbital trauma.

References

1. Sobel RK, Goldstein SM. Trochlear

calcification: A common entity. Orbit 2012;31:94-6. Crossref

2. Xiao TL, Kalariya NM, Yan ZH, et al.

Trochlear calcification and intraorbital foreign body in ocular trauma

patients. Chin J Traumatol 2009;12:210-3.

3. Shriver EM, McKeown CA, Johnson TE.

Trochlear calcification mimicking an orbital foreign body. Ophthal Plast

Reconstr Surg 2011;27:143-4. Crossref

4. Buch K, Nadgir RN, Tannenbaum AD,

Ozonoff A, Fujita A, Sakai O. Clinical significance of trochlear

calcifications in the orbit. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2014;35:573-7. Crossref

5. Nasr AM, Haik BG, Fleming JC, Al-Hussain

HM, Karcioglu ZA. Penetrating orbital injury with organic foreign bodies.

Ophthalmology 1999;106:523-32. Crossref