DOI: 10.12809/hkmj177060

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

MEDICAL PRACTICE

The current treatment landscape of irritable

bowel syndrome in adults in Hong Kong:

consensus statements

Justin CY Wu, MB, ChB, MD1;

Annie OO Chan, MB, ChB, PhD2;

Yawen Chan, MSocSci3;

Gordon CL Cheung, MPhil, RD (UK)4;

TK Cheung, MB, BS, PhD5;

Ambrose CP Kwan, MB, BS5;

Vincent KS Leung, MB, BS6;

Arthur DP Mak, MB, BS, MRCPsych7;

WC Sze, MB, BS, GradDFM5;

Raymond Wong, MD, PhD5

1 Department of Medicine and Therapeutics, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong

2 Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Hong Kong Sanatorium & Hospital, Happy Valley, Hong Kong

3 Hong Kong Institute of Integrative Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong

4 Hong Kong Nutrition Association, Hong Kong

5 Private specialist in Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Hong Kong

6 Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Hong Kong Baptist Hospital, Kowloon Tong, Hong Kong

7 Department of Psychiatry, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Prof Justin CY Wu (justinwu@cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Objective: The estimated prevalence of irritable

bowel syndrome in Hong Kong is 6.6%. With the

increasing availability of pharmacological and

non-pharmacological treatments, the Hong Kong

Advisory Council on Irritable Bowel Syndrome has

developed a set of consensus statements intended

to serve as local recommendations for clinicians

about diagnosis and management of irritable bowel

syndrome.

Participants: A multidisciplinary group of

clinicians constituting the Hong Kong Advisory

Council on Irritable Bowel Syndrome—seven

gastroenterologists, one clinical psychologist, one

psychiatrist, and one nutritionist—convened on 20

April 2017 in Hong Kong.

Evidence: Published primary research articles, meta-analyses,

and guidelines and consensus statements

issued by different regional and international

societies on the diagnosis and management of

irritable bowel syndrome were reviewed.

Consensus Process: An outline of consensus

statements was drafted prior to the meeting.

All consensus statements were finalised by the

participants during the meeting, with 100%

consensus.

Conclusions: Twenty-four consensus statements

were generated at the meeting. The statements

were divided into four parts covering: (1) patient

assessment; (2) patient’s psychological distress; (3)

dietary and alternative approaches to managing

irritable bowel syndrome; and (4) evidence to

support pharmacological management of irritable

bowel syndrome. It is recommended that primary

care physicians assume the role of principal care

provider for patients with irritable bowel syndrome.

The current statements are intended to guide primary

care physicians in diagnosing and managing patients

with irritable bowel syndrome in Hong Kong.

Introduction

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a common

condition encountered by primary care physicians,

with an estimated local prevalence of 6.6%,1 yet it

remains poorly understood. Irritable bowel syndrome

is believed to be a multifactorial disease involving

motility dysfunction, visceral hypersensitivity,

psychiatric co-morbidity, neuroendocrine

dysfunction, genetics and epigenetics, dysbiosis,

diet, and immune activation.2

First-line pharmacological treatment for IBS

may include smooth muscle relaxants, antidiarrhoeal

drugs, or laxatives. Nonetheless significant recent

advances have been made in the understanding of IBS

and new treatment modalities have emerged, such

as dietary modifications and the use of probiotics,

as well as pharmacological therapies, including

antidepressants, non-systemic antibiotics, serotonin-receptor

modulators, chloride channel activators,

guanylate cyclase C receptor agonists, mixed µ- and

κ-opioid receptor agonist and δ antagonists, and

alpha 2 δ ligands. Traditional Chinese medicine,

including herbal medicine and acupuncture, which

is valued by many Hong Kong Chinese people as an

important form of complementary medical care, has

also been investigated as a treatment for IBS.

The current standard of diagnosis and

management of IBS is based principally on data from

western studies; nonetheless cultural differences

must be considered in local practice, including

the differences in perception of symptoms, dietary

trends, and treatment goals within the Hong Kong

Chinese population.

For this reason, the Hong Kong Advisory

Council on IBS developed a set of consensus

statements offering guidance on the diagnosis and

management of IBS in Hong Kong.

Methods

A multidisciplinary group of clinicians constituting

the Hong Kong Advisory Council on IBS—seven

gastroenterologists, one clinical psychologist, one

psychiatrist, and one nutritionist—convened on 20

April 2017 in Hong Kong. An outline of consensus

statements was created prior to the meeting; this

was divided into four parts covering: (1) patient

assessment; (2) psychological distress; (3) dietary

and alternative approaches to managing IBS; and (4)

evidence for pharmacological management of IBS.

Published primary research articles, meta-analyses,

and guidelines and consensus statements issued by

different regional and international societies on the

diagnosis and management of IBS were reviewed

during the meeting. All consensus statements were

finalised by the participants during the meeting,

with 100% unanimity.

Results

Patient assessment—from primary care to diagnosis

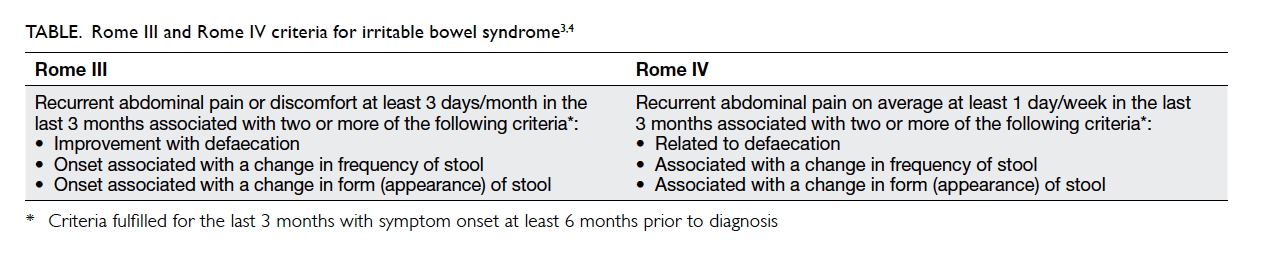

Statement 1: The Rome IV criteria allow for an

objective diagnosis of IBS. The long-term duration

of symptoms required by the criteria to make a

diagnosis, however, is too restrictive. Patients with a

shorter duration of symptoms should also be treated

for IBS.

The revised Rome IV criteria specify abdominal

pain as a requirement for diagnosis of IBS,3 while the

former Rome III criteria specified abdominal pain

or discomfort (Table).4 Due to cultural differences

and connotations of the word ‘pain’ in Chinese

languages, Chinese patients are more likely to

complain of ‘bloating’ and ‘discomfort’ than ‘pain’

when they were describing their symptoms.5 Patients

with abdominal discomfort or bloating without pain

as the dominant symptom should also be considered

for diagnosis of IBS in real-life clinical practice.

Statement 2: Physicians should make a positive

symptom-based clinical diagnosis; there are no

confirmatory diagnostic tests for IBS.3

Physicians should exercise clinical judgement

in determining appropriate investigations (eg blood

tests, stool tests, diagnostic imaging), considering

age, family history, and the presence of alarming

symptoms.6 Specific investigations such as

colonoscopy or abdominal imaging are not routinely

recommended in patients younger than 50 years

without specific risk factors.7

Statement 3: Inflammatory bowel disease

(Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis) and colorectal

cancer are the most important differential diagnoses

of IBS and should be actively excluded in patients

who present with IBS-related symptoms.6 8

Additional differential diagnoses include

enteric infections, medications, gynaecological

pathologies in female patients (eg endometriosis,

uterine fibroids, pelvic inflammatory disease),

pancreatic disorders, metabolic diseases (eg

hypercalcaemia), and ischaemic bowel disease in

elderly patients.8 9

Statement 4: Primary care providers should

be the principal physicians to diagnose and manage

IBS.

Compared with specialists, primary care

providers have the advantage of being more familiar

with a patient and are able to provide medical

care with a holistic approach, which is important

when managing a multifaceted disease such as

IBS.6 Psychological well-being and lifestyle factors

(eg exercise, diet, stress-coping strategies, sleep)

should be addressed.6 Primary care providers

should also educate patients about the disease,

provide reassurance about prognosis, and manage

expectations of treatment.6 10 Primary care providers

should recognise alarming symptoms or indicators

suggestive of organic pathology of the gastrointestinal

tract (eg anaemia, weight loss, bleeding) or significant

health problems; referral to other disciplines should

be made where appropriate.6 11 It is also important

to recognise the risk of (unwarranted) frequent

consultations and specialist referrals that will cause

unnecessary stress for the patient and prolonged

anxiety regarding their health.10

Statement 5: The main treatment objectives

in IBS are: symptomatic relief, improved quality of

life, reduced functional impairment, education, and

empowerment.6

It is important for physicians to verbally

acknowledge to patients that they have a clinical

condition with bothersome symptoms, while

reassuring them about their fears of severe

underlying conditions or deterioration of health; or

to reassure patients about their prognosis in the case

of post-infectious IBS.10

Understanding the patient’s psychological

distress

Statement 6: Anxiety and depressive disorders are

mental morbidities that are commonly observed in

patients with IBS and should be actively screened for

and managed. Sleep disturbances may be a symptom

of more severe mental distress.

In a community-based survey in Hong Kong,

the prevalence of generalised anxiety disorder was

16.5% in patients with IBS, compared with 3.3%

in the general population (odds ratio [OR]=5.8).12

A Taiwanese cohort of 4689 patients also found

increased risks of depressive disorder (hazard ratio

[HR]=2.89; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.30-3.19),

anxiety disorder (HR=2.89; 95% CI, 2.42-3.46),

and sleep disorder (HR=2.47; 95% CI, 2.02-3.02) in

patients with IBS.13 In a cross-sectional study of 201

subjects with IBS, 67.2% were poor sleepers.14 The

correlation between sleep score and IBS severity was

independent of anxiety and depression; nonetheless

the prevalence of sleep disturbances was higher in

patients with co-morbid anxiety and depression.14

Statement 7: Mental health morbidities in

patients with IBS should be screened for in the

primary care setting. Patients with mental health

morbidities should be encouraged to consult mental

health professionals. Referral to a psychiatrist is

indicated for psychosis, suicidal ideation, violent

behaviour, or other life-threatening conditions.6

Hints of mental morbidities include14 15;

• persistently low mood and/or reduced enjoyment of pleasurable activities;

• multiple and extra-intestinal somatic symptoms;

• stress-related gastrointestinal symptoms;

• family history of mental illness;

• suicidal ideation or a history of such attempts;

• sleep disturbance;

• significant functional impairment; and

• health anxiety10:

o repeated investigations

o relentless search for health information

• persistently low mood and/or reduced enjoyment of pleasurable activities;

• multiple and extra-intestinal somatic symptoms;

• stress-related gastrointestinal symptoms;

• family history of mental illness;

• suicidal ideation or a history of such attempts;

• sleep disturbance;

• significant functional impairment; and

• health anxiety10:

o repeated investigations

o relentless search for health information

Standardised instruments (eg Patient Health

Questionnaire [PHQ]) can easily be administered to

facilitate clinical assessments. The PHQ is available

online in Cantonese and is appropriate for use in

primary care clinics.16 Mild-to-moderate anxiety

and depression can be managed in the primary

care setting. Physicians should routinely counsel

patients on the importance of mental health in the

management of IBS.

Counselling and face-to-face psychological

interventions have been found to be efficacious in

the management of IBS. A study of 149 patients

with moderate or severe IBS resistant to the

antispasmodic agent mebeverine found that the

addition of cognitive behavioural therapy, delivered

by primary care nurses, had a considerable initial

benefit on symptom severity compared with

mebeverine alone, with the benefit persisting after 3

and 5 months.17 Cognitive behavioural therapy also

showed a significant benefit on the work and social

adjustment scale that persisted 12 months after

therapy (mean reduction of 2.8 points).17 A meta-analysis

also demonstrated similar positive benefits

of cognitive behavioural therapy (HR=0.60; 95% CI,

0.44-0.83), dynamic psychotherapy (HR=0.60; 95%

CI, 0.39-0.93), hypnotherapy (HR=0.74; 95% CI,

0.63-0.87), and multi-component psychotherapy

(HR=0.72; 95% CI, 0.62-0.83) compared with control

treatment.18

Dietary and alternative approaches to

irritable bowel syndrome

Statement 8: A short trial of low-FODMAP diet

has been shown to improve symptoms of IBS.19

Involvement of dieticians may improve accuracy

and adherence to the low-FODMAP diet or other

specific diets.20

In a randomised, controlled, single-blind,

crossover trial, a low-FODMAP (fermentable

oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides,

and polyols) diet for 21 days led to a significant

improvement in symptoms of IBS (including

abdominal pain, bloating, passage of gas and

dissatisfaction with stool consistency) and quality

of life compared with a standard Australian diet.19

Possible mechanisms include a decrease in osmotic

diarrhoea, fermentation and altered gut microbiota,

immune activation and visceral sensitivity.21 22

Statement 9: Other dietary concerns that may

affect IBS include lactose intolerance, high-fat diet,

high-fibre diet, chilli, and gluten.

These can all be potential aggravators of IBS,

but do not apply to all patients.23 Coeliac disease and

non-coeliac gluten sensitivity are rare in Chinese

populations and therefore trial of a gluten-free diet

is not warranted in Chinese patients.24

Statement 10: Health care practitioners should

exercise caution in recommending excessively

restrictive diets that could lead to malnutrition,

quality of life impairment, or psychological distress

(as a result of the difficulty of adherence).

For selected patients on long-term restrictive

diets or with multiple food intolerances, referral to

a dietician may help to minimise the risk of nutrient

deficiency.20

Statement 11: The role of food allergy in the

pathophysiology of IBS in unclear. Routine food

allergy testing is not recommended.25

Statement 12: Herbal medicine has been shown

to be effective only if an individualised approach

is taken. This requires assessment by a Chinese

medicine practitioner.

The benefit of individualised herbal medicine

was shown in a 1998 study in which 116 patients

with IBS were randomised to receive placebo

(n=35), individualised (n=38), or a standard (n=43)

Chinese herbal medicine for 16 weeks.26 Only

the individualised treatment group maintained

improvement at 14 weeks after completion of

treatment.26 This was confirmed by a 2006 Hong Kong

study by Leung et al27 in 199 diarrhoea-predominant

IBS patients randomised to receive placebo (n=59)

or standard (n=60) Chinese herbal formula for 16

weeks. No differences in global or individual IBS

symptoms or quality of life were observed at any

follow-up visits.

Statement 13: The current evidence does not

support acupuncture as an effective treatment for

IBS.

A meta-analysis that evaluated evidence

from 17 randomised controlled trials reported

that acupuncture is not more effective than sham

treatment for improving symptom severity (P=0.36)

or quality of life (P=0.83).28

Pharmacological management of irritable

bowel syndrome

Statement 14: The currently approved drug classes

for treatment of IBS are antispasmodics, laxatives,

and antidiarrhoeal drugs.

Statement 15: There are good efficacy and

safety data to support antispasmodics as first-line

therapy for IBS.

A 2008 meta-analysis evaluated data from

22 randomised controlled trials comparing

antispasmodics (including otilonium bromide,

cimetropium, hyoscine, pinaverium, trimebutine,

rociverine, alverine, dicycloverine, mebeverine,

pirenzepine, prifinium, and propinox) with placebo.

Of 905 patients assigned to antispasmodics, 350

(39%) had persistent symptoms after treatment

compared with 485 (56%) of 873 allocated to placebo

(relative risk [RR]=0.68; 95% CI, 0.57-0.81; P<0.001).29

Otilonium bromide (RR=0.55; 95% CI, 0.31-0.97)

and hyoscine (RR=0.63; 95% CI, 0.51-0.78) were the

only antispasmodics to show consistent evidence of

efficacy. The most frequent adverse events were dry

mouth, dizziness and blurred vision, but none of the

trials reported any serious adverse events.29

It is important to recognise that not all

antispasmodics share the same efficacy and safety

profile. Moreover, there are additional safety concerns

(eg blurred vision, mental confusion, aggravation of

prostatism, tachycardia) with antispasmodics of the

anticholinergic subclass; additional monitoring is

required with such agents.30

Statement 16: There is a lack of head-to-head

studies comparing the efficacy and safety of different

antispasmodics. Moreover, antispasmodics have

varying mechanisms of action.

Hyoscine is an antispasmodic that blocks the

action of muscarinic and nicotinic acetylcholine

receptors in smooth muscle and secretory glands

causing decreased motility of the gastrointestinal

tract.31

Otilonium bromide is an antispasmodic with

several modes of action that are not shared by other

antispasmodics. It works by blocking L-type calcium

channels on smooth muscle cells thereby restoring

physiological motility. It also exhibits an antisecretory

effect and reduces spasm through inhibition of

muscarinic M3 receptor–coupled calcium signals.

Finally, otilonium bromide antagonises tachykinin

receptors on the intestinal smooth muscle cells and

afferent nervous terminations, thus modulating the

development of intestinal hyperalgesia and reducing

visceral hypersensitivity by enhancing sensory

thresholds to rectosigmoid distension.32

Statement 17: Otilonium bromide can be

prescribed by primary care physicians as first-line

therapy for IBS.

Data from a total of 883 patients with IBS from

three randomised controlled trials were included in

a pooled analysis. A significant therapeutic effect

of otilonium bromide was observed after 10 and 15

weeks of treatment compared with placebo, with

reference to intensity and frequency of abdominal

pain, severity of bloating, and rate of responders

as evaluated by patients and physicians.33 The

most common treatment-emergent adverse

events associated with otilonium bromide were

gastrointestinal events (abdominal pain, flatulence,

worsening IBS) and infections. Nearly all were mild

to moderate (99% in the otilonium bromide group

and 98% in the placebo group) and were considered

unrelated to the study treatment (92% in the

otilonium bromide group and 94% in the placebo

group).34

Statement 18: Further study is warranted to

establish an optimal treatment period for otilonium

bromide.

Many patients use otilonium bromide on an

as-needed basis or as prophylaxis prior to known

triggering events (eg travel, large meals). Others use

otilonium bromide on a long-term basis (eg those

with frequent daily symptoms). A randomised,

double-blind clinical trial demonstrated a lower

rate of symptom relapse (P=0.009) and higher

relapse-free probability (P=0.038) in patients treated

with otilonium bromide for 15 weeks compared

with patients treated with placebo.34 A 2-year

study demonstrated a significant improvement in

abdominal pain, abdominal distension, and bowel

movements in patients treated with otilonium

bromide, compared with a high-roughage diet.35

Statement 19: Antispasmodics are also

commonly prescribed in combination with

antidiarrhoeal drugs or laxatives. No clinical data,

however, are available on combination therapy.

Statement 20: Selective serotonin reuptake

inhibitors (SSRIs) are used in patients with co-morbid

anxiety or depressive disorder or as off-label

treatment for patients who do not respond to

first-line treatment for IBS. Treatment with SSRIs

requires close monitoring for efficacy and safety.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors have

proven efficacy for IBS, anxiety and depressive

disorders, and should be considered when organ-based

treatment and psychological treatment are

not accessible or effective. A meta-analysis of five

randomised controlled trials found that SSRIs were

more effective and better tolerated than placebo

as treatment for IBS (RR=0.62; 95% CI, 0.45-0.87).36 Nonetheless, SSRIs should be prescribed

by physicians or mental health professionals with

experience and training in antidepressant drug

treatment. Potential adverse events, including

suicidal ideation in non-suicidal patients,

warrants careful attention to patients taking

antidepressants.37

Statement 21: Probiotics have demonstrated

positive results in the treatment of IBS.

A 2013 meta-analysis found that probiotics

consisting of Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium,

Escherichia, Streptococcus or combination probiotics

had beneficial effects on the persistence of IBS

symptoms (RR=0.79; 95% CI, 0.70-0.89), global IBS,

abdominal pain, bloating and flatulence scores, and

led to an increase in the number of stools per week.38

The exact mechanism of action, optimal regimen and

delivery mode, and durability of efficacy remains to

be determined. Moreover, although adverse events

with probiotics are rare, there are little long-term

safety data available.38 Finally, the efficacy of different

probiotic strains is variable and limits their use as a

first-line treatment.38

Statement 22: Short-term rifaximin has been

found to be effective in relieving bloating symptoms.

Rifaximin is a poorly absorbed, luminally active

antibiotic. A meta-analysis of five studies found that

short-term use of rifaximin was effective in relieving

bloating symptoms (OR=1.55; 95% CI, 1.23-1.96)

and led to global IBS symptom improvement

(OR=1.57; 95% CI, 1.22-2.01).39 The role of rifaximin

has not been fully acknowledged in the management

algorithm of IBS owing to the concern of antibiotic

resistance, risk of Clostridium difficile infection, and

long-term effectiveness.

Statement 23: Other novel therapies that are

Food and Drug Administration–approved based

on positive results in patients with IBS, but are not

yet available in the primary care setting in Hong

Kong include: serotonin receptor modulators,

secretagogues, and peripherally acting opioid

receptor modulators.

Statement 24: There are insufficient efficacy

and safety data to justify the clinical use of faecal

microbiota transplantation in the management of

IBS.

Conclusions

Irritable bowel syndrome is a common disorder

encountered in general practice, yet effective

treatment remains a challenge for primary care

physicians and gastroenterologists. This is the first

consensus statement on the appropriate approach

to diagnosis and management of IBS in Hong Kong.

This paper summarises important considerations

in managing patients with IBS, along with clinical

efficacy and safety data on pharmacological

treatments. These consensus statements aimed to

provide local general practitioners with information

to counsel and manage patients with IBS in Hong

Kong.

The treatment of IBS depends on patient

symptoms.6 After actively excluding relevant and

serious pathologies, psychological and dietary

aspects of IBS should first be addressed.6

Food allergy testing is not recommended in

patients with IBS25; nonetheless important dietary

considerations include FODMAPs, fibre, chilli,

lactose, and gluten.23 Coeliac disease is rare in the

Chinese population; data suggest that wheat is not

completely absorbed in the small bowel and may

produce gastrointestinal symptoms.23 Although the

primary carbohydrate in the Chinese diet is rice,

there is a strong influence of western cuisine in Hong

Kong and wheat is found in many traditional Hong

Kong–style foods.

Anxiety and depression are common in

patients with IBS. Psychological interventions such

as counselling, cognitive behavioural therapy, and

hypnotherapy are effective treatments for patients

with mental morbidities and IBS.17 18 Physicians

should routinely counsel patients on the importance

of mental health in the management of IBS.

Motivated patients may consider traditional

Chinese medicine but an individualised approach

must be taken.26 At this time, there is insufficient

evidence to recommend acupuncture for patients

with IBS.28

The currently approved drug classes for

treatment of IBS are antispasmodics, laxatives,

and antidiarrhoeal drugs. Antispasmodics are a

heterogeneous drug class with varying mechanisms

of action. Otilonium bromide and hyoscine are the

only antispasmodics to show consistent evidence

of efficacy but the anticholinergic side-effect of

hyoscine has limited its frequent use in IBS.29 31

Acknowledgements

English language editing and writing support,

funded by an unrestricted educational grant from

A. Menarini Hong Kong Limited, was provided by

Cassandra Thomson of MIMS (Hong Kong) Limited.

Declaration

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of

interest.

References

1. Kwan AC, Hu WH, Chan YK, Yeung YW, Lai TS, Yuen H.

Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in Hong Kong. J

Gastroenterol Hepatol 2002;17:1180-6. Crossref

2. Camilleri M. Peripheral mechanisms in irritable bowel

syndrome. N Engl J Med 2012;367:1626-35. Crossref

3. Lacy BE, Mearin F, Chang L, et al. Bowel disorders.

Gastroenterology 2016 Feb 18. Epub ahead of print. Crossref

4. Shih DQ, Kwan LY. All roads lead to Rome: update on Rome

III criteria and new treatment options. Gastroenterol Rep

2007;1:56-65.

5. Gwee KA, Lu CL, Ghoshal UC. Epidemiology of irritable

bowel syndrome in Asia: something old, something

new, something borrowed. J Gastroenterol Hepatol

2009;24:1601-7. Crossref

6. Khanbhai A, Singh Sura D. Irritable bowel syndrome for

primary care physicians. Br J Med Pract 2013;6:a608.

7. Hong Kong Department of Health. About colorectal

cancer 2016. Available from: http://www.colonscreen.gov.

hk/en/public/about_crc/who_should_be_screened_and_who_need_not_be_screened.html. Accessed 1 Jun 2017.

8. Zammit E. The irritable bowel syndrome. Malta Med J

2009;21:34-40.

9. Cartwright SL, Knudson MP. Evaluation of acute abdominal

pain in adults. Am Fam Physician 2008;77:971-8.

10. O’Sullivan MA, Mahmud N, Kelleher DP, Lovett E,

O’Morain CA. Patient knowledge and educational needs

in irritable bowel syndrome. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol

2000;12:39-43. Crossref

11. Hookway C, Buckner S, Crosland P, Longson D. Irritable

bowel syndrome in adults in primary care: summary of

updated NICE guidance. BMJ 2015;350:h701. Crossref

12. Lee S, Wu J, Ma YL, Tsang A, Guo WJ, Sung J. Irritable

bowel syndrome is strongly associated with generalized

anxiety disorder: a community study. Aliment Pharmacol

Ther 2009;30:643-51. Crossref

13. Lee YT, Hu LY, Shen CC, et al. Risk of psychiatric disorders

following irritable bowel syndrome: a nationwide population-based

cohort study. PLoS One 2015;10:e0133283. Crossref

14. Moradian-Shahrbabaki M, Vahedi H, Sadeghniiat-Haghighi K, Shamsipour M. Tracing the relationships

between sleep disturbances and symptoms of irritable

bowel syndrome. J Sleep Sci 2016;1:101-8.

15. Fadgyas-Stanculete M, Buga AM, Popa-Wagner A,

Dumitrascu DL. The relationship between irritable bowel

syndrome and psychiatric disorders: from molecular

changes to clinical manifestations. J Mol Psychiatry

2014;2:4. Crossref

16. Yu X, Stewart SM, Wong PT, Lam TH. Screening for

depression with the Patient Health Questionnaire–2

(PHQ-2) among the general population in Hong Kong. J

Affect Disord 2011;134:444-7. Crossref

17. Kennedy T, Jones R, Darnley S, Seed P, Wessely S, Chalder T.

Cognitive behaviour therapy in addition to antispasmodic

treatment for irritable bowel syndrome in primary care:

randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2005;331:435. Crossref

18. Ford AC, Quigley EM, Lacy BE, et al. Effect of antidepressants

and psychological therapies, including hypnotherapy, in

irritable bowel syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis.

Am J Gastroenterol 2014;109:1350-65. Crossref

19. Halmos EP, Power VA, Shepherd SJ, Gibson PR, Muir JG. A

diet low in FODMAPs reduces symptoms of irritable bowel

syndrome. Gastroenterology 2014;146:67-75.e5. Crossref

20. Nanayakkara WS, Skidmore PM, O’Brien L, Wilkinson TJ,

Gearry RB. Efficacy of the low FODMAP diet for treating

irritable bowel syndrome: the evidence to date. Clin Exp

Gastroenterol 2016;9:131-42.

21. Hayes PA, Fraher MH, Quigley EM. Irritable bowel

syndrome: the role of food in pathogenesis and management.

Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2014;10:164-74.

22. De Palma G, Reed DE, Pigrau M, et al. Diet-microbiota

interactions underlie symptoms’ generation in IBS.

Gastroenterology 2017;152(5 Suppl 1):S160. Crossref

23. Gonlachanvit S. Are rice and spicy diet good for functional

gastrointestinal disorders? J Neurogastroenterol Motil

2010;16:131-8. CrossRef

24. Jiang LL, Zhang BL, Liu YS. Is adult celiac disease really

uncommon in Chinese? J Zhejiang Univ Sci B 2009;10:168-71. Crossref

25. Kennedy DA, Lewis E, Cooley K, Fritz H. An exploratory

comparative investigation of Food Allergy/Sensitivity

Testing in IBS (the FAST study): a comparison between

various laboratory methods and an elimination diet. Adv

Integr Med 2014;1:124-30. Crossref

26. Bensoussan A, Talley NJ, Hing M, Menzies R, Guo A, Ngu

M. Treatment of irritable bowel syndrome with Chinese

herbal medicine: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA

1998;280:1585-9. Crossref

27. Leung WK, Wu JC, Liang SM, et al. Treatment of diarrhea-predominant

irritable bowel syndrome with traditional

Chinese herbal medicine: a randomized placebo-controlled

trial. Am J Gastroenterol 2006;101:1574-80. Crossref

28. Manheimer E, Wieland LS, Cheng K, et al. Acupuncture

for irritable bowel syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis.

Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107:835-47. Crossref

29. Ford AC, Talley NJ, Spiegel BM, et al. Effect of fibre,

antispasmodics, and peppermint oil in the treatment of

irritable bowel syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis.

BMJ 2008;337:a2313. Crossref

30. Hesch K. Agents for treatment of overactive bladder:

a therapeutic class review. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent)

2007;20:307-14.

31. Samuels LA. Pharmacotherapy update: hyoscine

butylbromide in the treatment of abdominal spasms. Clin

Med Ther 2009;1:647-55. Crossref

32. Triantafillidis JK, Malgarinos G. Long-term efficacy

and safety of otilonium bromide in the management of

irritable bowel syndrome: a literature review. Clin Exp

Gastroenterol 2014;7:75-82. Crossref

33. Clavé P, Tack J. Efficacy of otilonium bromide in

irritable bowel syndrome: a pooled analysis. Therap Adv

Gastroenterol 2017;10:311-22. Crossref

34. Clavé P, Acalovschi M, Triantafillidis JK, et al. Randomised

clinical trial: otilonium bromide improves frequency

of abdominal pain, severity of distention and time to

relapse in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment

Pharmacol Ther 2011;34:432-42. Crossref

35. Villagrasa M, Boix J, Humbert P, Quer JC. Aleatory clinical

study comparing otilonium bromide with a fiber-rich

diet in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Ital J

Gastroenterol 1991;23(8 Suppl 1):67-70.

36. Ford AC, Talley NJ, Schoenfeld PS, Quigley EM, Moayyedi

P. Efficacy of antidepressants and psychological therapies

in irritable bowel syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis.

Gut 2009;58:367-78. Crossref

37. Bielefeldt AØ, Danborg PB, Gøtzsche PC. Precursors to

suicidality and violence on antidepressants: systematic

review of trials in adult healthy volunteers. J R Soc Med

2016;109:381-92. Crossref

38. Ford AC, Quigley EM, Lacy BE, et al. Efficacy of prebiotics,

probiotics, and synbiotics in irritable bowel syndrome and

chronic idiopathic constipation: systematic review and

meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2014;109:1547-61. Crossref

39. Menees SB, Maneerattannaporn M, Kim HM, Chey WD.

The efficacy and safety of rifaximin for the irritable bowel

syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J

Gastroenterol 2012;107:28-35. Crossref