DOI: 10.12809/hkmj166086

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Management of an incidental finding of right internal jugular vein agenesis

Vincent KF Kong, FANZCA, FHKAM (Anaesthesiology); CJ Jian, MB, BS; R Ji, MS, MB, BS; Michael G Irwin, MD, FHKAM (Anaesthesiology)

Department of Anaesthesia, HKU-Shenzhen Hospital, 1 Haiyuan Road, Futian District, Shenzhen, China

Corresponding author: Dr Vincent KF Kong (vincentkong@hku.hk)

Case report

A 43-year-old woman was referred to the University

of Hong Kong–Shenzhen Hospital in August

2016 with a 10-year history of hepatolithiasis.

Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen

demonstrated multiple stones in the right posterior

portion of the liver, the common biliary duct, and

the gallbladder. Dilatation and inflammation of

both intra- and extra-hepatic ducts were apparent

and an elective right hepatectomy along with a

Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy was arranged.

Preoperative physical examination was normal apart

from hypertension (168/105 mm Hg). Laboratory

tests revealed a microcytic, hypochromic anaemia

(haemoglobin, 97 g/L), hyperuricaemia, and mildly

elevated alkaline phosphatase. Liver/renal function,

clotting profile, chest X-ray, and electrocardiogram

were all normal. General anaesthesia was induced

intravenously with propofol and remifentanil using

a target-controlled infusion (Marsh model) under

the guidance of the Bispectral Index monitoring

system (Covidien, Boulder [CO], US). Tracheal

intubation was performed following administration

of rocuronium and anaesthesia maintained

intravenously with intermittent positive pressure

ventilation in oxygen and air. The patient was

positioned for right internal jugular vein (IJV)

cannulation.

Pre-insertion sonographic evaluation of the

right cervical region (SonoSite M-Turbo, Bothell

[WA], US) using a linear, high-frequency transducer

(HFL38, 6-13 MHz) revealed only a single pulsatile

vessel that was non-compressible and suggestive of

the right carotid artery. The characteristic pulsatile

blood flow was confirmed by Doppler. There was

no evidence of the right IJV despite repositioning of

the patient’s head, use of minimal pressure on the

probe with colour flow mapping, and the application

of Valsalva manoeuvre. Ultrasonography of the

left side showed normal anatomy with good size

of IJV. Following a brief discussion, the consultant

anaesthetist and the surgeon decided to proceed

with surgery without a central venous catheter. At the

end of liver resection, the patient began to develop

hypotension that was marginally responsive to fluid resuscitation and moderate-dose phenylephrine

infusion through the large-bore peripheral lines.

The operation lasted approximately 5 hours with

a total blood loss of 350 mL. Tracheal intubation

was continued postoperatively and the patient

was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU).

Central venous cannulation was not attempted by

ICU physicians and the patient was extubated on

postoperative day 1 and discharged from the ICU

on postoperative day 4. The patient was followed up

by the attending and consultant anaesthetists after

surgery. The incidental finding of her neck condition

was explained and she agreed to undergo further

investigations for a possible vascular anomaly.

Ultrasonography (iU Elite model with a L12-5

transducer; Philips Medical System, Bothell [WA],

US) of the neck by a radiologist on postoperative day

5 confirmed the absence of thrombosis and the right

IJV. The left IJV was normal (diameter, 15-19 mm).

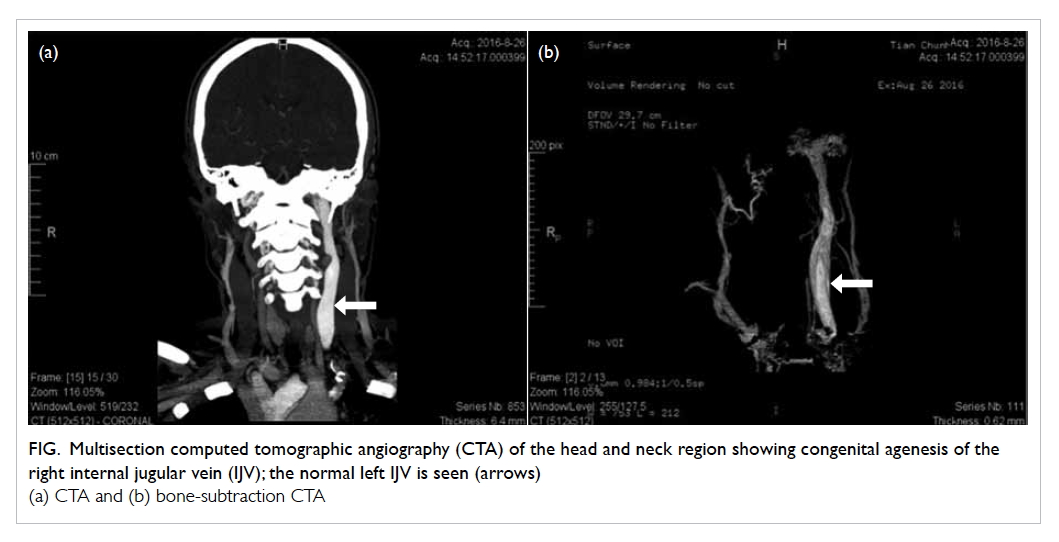

Multisection CT angiography of the head and neck

region revealed agenesis of the right IJV (Fig). There

was no other vascular anomaly in the head and neck

region. The patient was discharged from hospital on

day 11 postoperatively.

Figure. Multisection computed tomographic angiography (CTA) of the head and neck region showing congenital agenesis of the right internal jugular vein (IJV); the normal left IJV is seen (arrows)

(a) CTA and (b) bone-subtraction CTA

Discussion

Non-visualisation of the right IJV on two-dimensional

sonographic scanning can be due to operator (eg

suboptimal patient positioning, inappropriate

machine setting, and excessive pressure on the probe)

and patient (eg vascular thrombosis, congenital

anomalies such as hypoplasia, agenesis) factors.

Congenital agenesis of the IJV is an extremely rare

anomaly.1 The risks associated with central venous

cannulation of the left IJV or the right subclavian vein

in our patient before surgery may have outweighed

the benefits. The IJVs are the principal vessels for

cerebral venous drainage. Injury and/or thrombosis

of the left IJV can still occur even if proper precautions

are taken during catheterisation. Disruption of the

alternative channels of venous drainage from the

cranial cavity in a patient with congenital agenesis

of the IJV may have serious consequences. Vascular

malformations in the head and neck region result

from embryological developmental deformities and can co-exist asymptomatically. Further diagnostic

analysis before cannulation of her right subclavian

vein would have provided extra safety.

Low central venous pressure (CVP) during

anaesthesia reduces surgical blood loss in major

hepatic resection,2 and central venous cannulation

of the right IJV to enable CVP monitoring has

become a routine practice in many places prior

to major hepatectomy. Less invasive techniques

such as peripheral venous pressure and external

jugular venous pressure measurement allow

an acceptable estimation of the CVP with less

associated morbidity and mortality. Stroke volume

variation (SVV) derived from the Vigileo-FloTrac

system (Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine [CA], US) can

be a safe and effective alternative to conventional

CVP monitoring during hepatic resection.3 The

FloTrac system is based on arterial pulse contour

analysis and does not require external calibration,

thermodilution, or dye dilution. Unlike CVP that is a

favoured but static measure of intravascular volume,

SVV monitors dynamically the physiological

interactions of the heart and lungs in mechanically

ventilated patients to not only estimate fluid status

but also predict fluid responsiveness. A high SVV of

10% to 20% is associated with significantly less blood

loss during liver resection.4 Nonetheless a multi-parametric

approach should be adopted to guide

fluid management in complicated cases because

every haemodynamic variable has limitations and

interferes with other variables.

Anaesthetists should function as perioperative physicians to minimise patient harm and create

extra value to the episode of patient care. A simple,

focused ultrasound examination of the neck during

preoperative assessment can diagnose variation

in vessel position or abnormalities of the vessel. It

has been recommended by the National Institute

for Health and Care Excellence in the United Kingdom since

20025 and this report further supports its routine

use. Early recognition of these anomalies enables

extra precautions to be taken (eg discussion with

the patient and surgeons for alternative anaesthetic

plans, cannulation sites, monitoring strategies,

and further investigation before surgery) to reduce

patient harm.

References

1. Kayiran O, Calli C, Emre A, Soy FK. Congenital agenesis of

the internal jugular vein: an extremely rare anomaly. Case

Rep Surg 2015;2015:637067.

2. Wang WD, Liang LJ, Huang XQ, Yin XY. Low central

venous pressure reduces blood loss in hepatectomy. World

J Gastroenterol 2006;12:935-9. Crossref

3. Reineke R, Meroni R, Votta C, et al. Enhanced recovery after

open hepatectomy with minimally invasive haemodynamic

monitoring: A successful challenge. A comparative study

from a single institution. Clin Nutr ESPEN 2016;12:e53-4. Crossref

4. Dunki-Jacobs EM, Philips P, Scoggins CR, McMasters

KM, Martin RC 2nd. Stroke volume variation in hepatic

resection: a replacement for standard central venous

pressure monitoring. Ann Surg Oncol 2014;21:473-8. Crossref

5. Kong V, Yuen M, Irwin M. Perioperative ultrasonography:

Ultrasound and vascular cannulation. CPD Anaesthesia

2007;9:3-9.