Hong Kong Med J 2017 Jun;23(3):272–81 | Epub 5 May 2017

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj165061

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

REVIEW ARTICLE CME

Common urological problems in children:

inguinoscrotal pathologies

Ivy HY Chan, FRCSEd(Paed), FHKAM (Surgery);

Kenneth KY Wong, PhD, FHKAM (Surgery)

Division of Paediatric Surgery, Department of Surgery, The University of

Hong Kong, Queen Mary Hospital, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Kenneth Wong (kkywong@hku.hk)

Abstract

Urological problems in children are often

encountered in general clinical practice. This review

forms the second paper of our series on common

urological problems in children about inguinoscrotal

pathologies. We aimed to provide concise

information for doctors who are unfamiliar with this

topic.

Introduction

Our previous review paper described and discussed

disorders of the prepuce.1 In this paper, we focus on

common inguinoscrotal pathologies in children.

Inguinal hernia/hydrocoele, undescended testis,

acute scrotum, and varicocoele will be discussed.

These have a broad disease spectrum, but may have

similar clinical presentation and may be discovered

by parents, during routine paediatric assessment

or incidentally in the clinic. Despite advances in

medical technology, proper history taking, physical

examination, and understanding of these conditions

remain crucial for management and specialist

referral.

Inguinal hernia/hydrocoele

These two conditions account for most of the

pathologies in the inguinoscrotal region in children.

For paediatric inguinal hernia, the cumulative

incidence was reported to be 6.62% in boys up to 15

years old in a nationwide study in Taiwan: one in 15

boys would develop inguinal hernia before the age

of 15 years.2

Both inguinal hernia and hydrocoele occur

because of non-closure of the processus vaginalis

(patent processus vaginalis). The processus vaginalis

forms an extension of the peritoneum during the

time of testicular descent into the scrotum in the

fetus. It normally undergoes fusion or closure when

testicular descent is complete. Failure to close

may result in either inguinal hernia or hydrocoele,

depending on the size of the defect. If it remains

patent or unfused in girls, it becomes the canal of

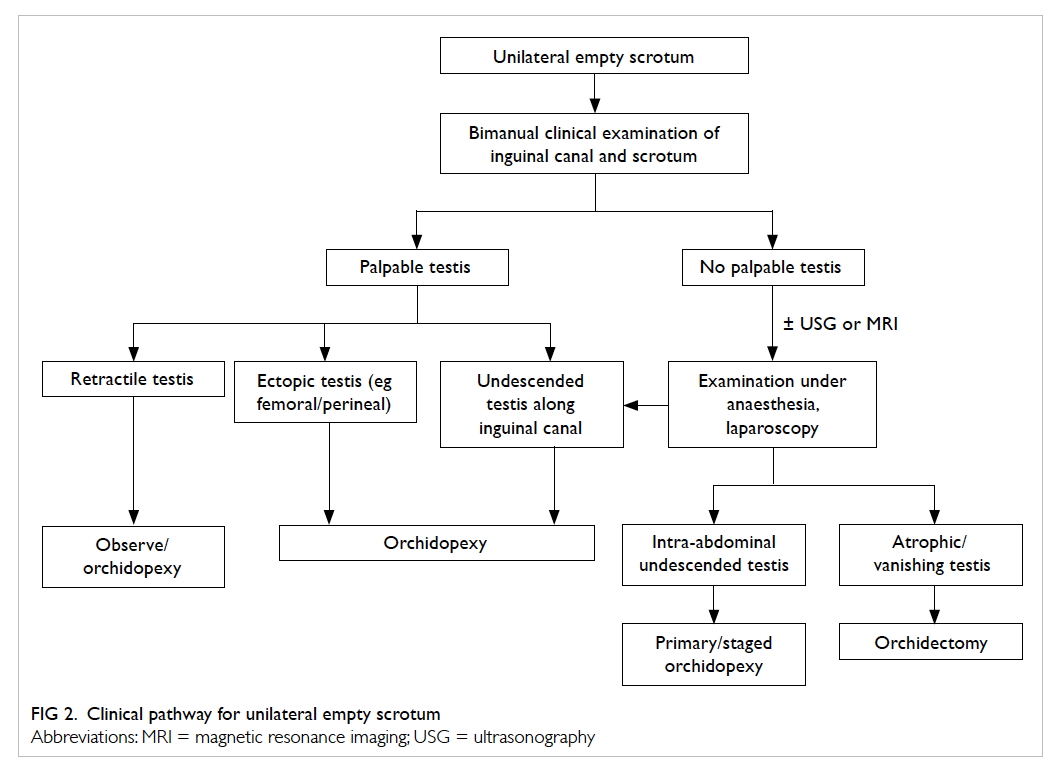

Nuck and may also result in inguinal hernia (Fig 1).

Figure 1. (a) Normal, (b) indirect inguinal hernia or communicating hydrocoele, both pathologies with patent processes vaginalis (PPV), (c) hydrocoele of cord with obliterated PPV and fluid collected in the cord, and (d) scrotal hydrocoele with obliterated PPV with excessive fluid around the testis

The incidence of inguinal hernia is highest

in children under 1 year of age and thereafter

decreases.2 In premature babies, the incidence is

even higher with babies born less than 32 weeks of

gestation having a reported incidence of 9.34%.3

Right-sided hernias are more common (ratios

of right, left, and bilateral hernia are approximately

59%, 29%, and 12%, respectively).4 Boys are affected

around 10 times more often than girls2; 99% of

inguinal hernias in children are of the indirect type.4

Hydrocoele is an abnormal collection

of fluid along the processus vaginalis, and can

be communicating or non-communicating. In

communicating hydrocoele, there is a patent

processus vaginalis. Non-communicating hydrocoele

includes scrotal hydrocoele and hydrocoele of cord,

and here the processus vaginalis is obliterated

with the collection of fluid in the tunica vaginalis.

Hydrocoele can present in infants or older children

and its management differs. For hydrocoele that

presents before 1 year of age, there is a 62.7% to

89% chance of spontaneous complete resolution or

significant improvement,5 6 7 with the mean time of

resolution being about 6 months. Thus, it is worth

allowing a period of time to observe a hydrocoele

provided other conditions like inguinal hernia or

testicular pathology have been excluded.

Clinical features

Parents usually notice the inguinoscrotal pathology

in their child during bathing or changing nappies. A

painless bulge over the inguinal region or even down

to the scrotum may be seen in boys, or a bulge over

the vulva in girls with inguinal hernia. The bulge will

increase in size when the child cries and decrease

when lying down. A proper clinical examination may

not be easy in the clinic setting for children and the

hernia may not be apparent. A well-taken clinical

history is very important in making the correct

diagnosis. An ‘intermittent inguinal swelling’ may

indicate an inguinal hernia. A static painless scrotal

swelling may indicate a scrotal/encysted hydrocoele.

For children who cooperate, the upper and

lower extent of the inguinoscrotal mass should be

carefully examined. The upper extent of an inguinal

hernia should start at the internal ring, that is, the

midpoint between the pubic tubercle and anterior

superior iliac spine. For scrotal/encysted hydrocoele,

clinicians should be able to get above the lesions. A

transillumination test is a very helpful in adults but is

not reliable in infants/small children. Because of the

thin bowel wall the transillumination test can also

be positive in infants/small children with inguinal

hernia.

Pain and inconsolable crying in a child with

a tender irreducible inguinal bulge may indicate

an incarcerated inguinal hernia. A younger child is

more likely to be affected. The mean age of hernia

incarceration was shown to be 1.5 years in a previous

study.4 The incidence of incarceration is 3 times

higher in premature babies with inguinal hernia.

Very often, parents may not be able to describe

the clinical features properly and no pathology can

be demonstrated during a clinic visit. We suggest

that parents take a clinical photo using mobile

phones at home, which can be shown to the doctor

during the subsequent clinic visit.

Investigations

Diagnosis of an inguinal hernia depends largely on

clinical history and physical examination. Different

imaging techniques can sometimes be helpful in

making the diagnosis. Contrast herniography is only

of historical interest because of its invasiveness.

Ultrasonography (USG) of the inguinal canal to

detect occult inguinal hernia has been described and

its use varies in different countries. Studies show

that the preoperative USG can decrease the future

risk of developing metachronous inguinal hernia.8

A positive finding on USG strongly correlates with

positive operative findings.9 10 Nonetheless as the accuracy of USG is largely operator-dependent, we

feel that while a positive USG finding is strongly

suggestive of a clinical hernia, a negative finding

should be interpreted with care. Diagnosis of

inguinal hernia will very much depend on clinical

examination. Of note, USG of the inguinal canal is

not a routine procedure when making a diagnosis

of inguinal hernia. It may serve as an adjunct when

there is doubt about incarcerated hernia versus

hydrocoele of cord or concern about underlying

testicular pathology for hydrocoele.

Indications and timing of surgery

Once the diagnosis of inguinal hernia is made,

operation is indicated regardless of age due to

the risk of incarceration, with a reported rate of

approximately 4.19% to 8.2%.2 11 As young children and infants have a higher risk of incarceration, it

may be wise to arrange earlier operation. Surgery,

however, should still be arranged as early as possible

in an otherwise healthy child.

For the management of premature babies with

inguinal hernia, there are many factors that should

be taken into consideration such as postoperative

apnoea, respiratory distress, co-morbidities (eg

chronic lung disease in premature babies), and risk

of incarceration. There is always debate about the

optimal timing of hernia repair in premature babies,

that is, surgery just before discharge from neonatal

intensive care unit or when the child is older. Although

a long waiting time is associated with higher risk of

incarceration in infants and premature babies, and

emergency repair in patients with incarceration

is associated with a higher likelihood of testicular

atrophy,12 13 14 surgery is less technically demanding

in older babies. Fewer perioperative morbidities are

also observed when performing surgery later. Early

inguinal hernia repair is associated with prolonged

hospital stay and prolonged intubation.15 A study

from Hong Kong reported one (1.3%) incarceration

in 79 premature patients with a mean body weight

at operation of 4360 g.16 This incarceration rate is

relatively lower when compared with other studies—9% to 21% by Lautz et al13 from the United States, and 5.2% to 10.1% by Zamakhshary et al12 from

Canada. It is likely to be due to the shorter travelling

time between a patient’s home and hospital in Hong

Kong. Based on our experience, it is reasonable in

Hong Kong to wait for surgery until premature babies

have achieved a reasonable body weight. Parents

should be taught how to observe the symptoms and

signs of incarceration before discharge. If the patient

lives unreasonably far from the hospital and parents

are not able to observe the symptoms and signs of

incarceration, earlier surgery should be offered.

From our perspective, we would offer repair when

the patient’s body weight reaches 2.5 kg, provided

there are no other indications for earlier or delayed

repair.

As mentioned earlier, there is a high chance

of spontaneous resolution of infantile hydrocoele

during the first year of life. Patients should therefore

be observed and monitored in the first 1 to 2 years

of life.5 6 Parents should also be taught about the symptoms and signs of inguinal hernia during

this observation period as an inguinal hernia may

present as a communicating hydrocoele on first

sight. Patients with persistent hydrocoele, giant or

symptomatic hydrocoele, hydrocoele associated

with inguinal hernia or other conditions (eg presence

of ventriculoperitoneal shunt), or who require

peritoneal dialysis should be offered surgery.

Open versus laparoscopic surgery

Open high ligation of patent processus vaginalis was

the mainstay of treatment for both inguinal hernia and

hydrocoele in children until the advent of laparoscopic

surgery. Different laparoscopic techniques are largely

categorised into intracorporeal or extracorporeal

ligation of the patent processus vaginalis.17 18 19

Benefits of laparoscopic surgery include the possible

visualisation of the contralateral deep ring and better

cosmetic outcome. Yet it may incur a higher set-up

cost or longer operating time.

Two recent systematic reviews/meta-analyses

showed very similar results when comparing open and

laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair in children.17 20 Both studies showed no significant difference in

recurrence rate. Esposito et al17 reported a 1.4%

recurrence rate following laparoscopic repair and

1.6% following open repair. For operating time, they

noted a significantly shorter time for laparoscopic

repair of bilateral hernia when compared with

an open approach. There was no difference for

unilateral hernia repair. Feng et al20 reported that a

laparoscopic extraperitoneal method had a much

shorter operating time in both unilateral and bilateral

hernia repair. Lower pain scores were also reported

in two randomised controlled trials for laparoscopic

repair.21 22

Feng et al20 further showed more testicular

complications in open repair. Another retrospective

review showed similar results.23 Of note, a higher

recurrence rate of up to 3.4% for laparoscopic

repair was observed in the early era of laparoscopic

surgery.18 There is no consensus, however, on

whether a laparoscopic or open approach is superior.

In contrast to laparoscopic inguinal hernia

repair, laparoscopic repair of hydrocoele has not

received the same popularity, with open high ligation

still being the mainstay of treatment. Indeed, only a

handful of studies can be found in the literature.

One reason may be the belief that the deep ring

is already closed. A recent study noted that 97%

of patients with a clinically non-communicating

hydrocoele had a patent processus vaginalis during

laparoscopy.24 Among the small number of reports,

Saka et al19 showed no significant difference in terms

of outcome between open and laparoscopic repair of

hydrocoele.

Contralateral exploration

Metachronous contralateral inguinal hernia

(MCH)—presence of contralateral inguinal hernia—may present in some patients after successful repair

of inguinal hernia. An initial presentation with left-sided

hernia,25 26 27 and prematurity are risk factors for

MCH.

Before the era of laparoscopy, USG of the groin

or routine contralateral exploration were suggested

by some surgeons to reduce the risk of MCH and the

need for second operation/anaesthesia. Miltenburg et al28 reviewed the use of laparoscopic evaluation and concluded that it could successfully decrease the

incidence of MCH.

Today, routine examination during

laparoscopic hernia repair has shown the rate of

contralateral patent contralateral processus vaginalis

(CPPV) to be 30% to 39.7%.25 29 Yet, a meta-analysis revealed that only 6% of all patients returned with

MCH after unilateral inguinal hernia repair.26 Thus,

the presence of CPPV does not necessarily equate to

subsequent clinical inguinal hernia. Kokorowski et al29 concluded that patent processus vaginalis might be over-treated. Repair of the patent processus

vaginalis will definitely decrease the risk of MCH, the

costs, and the risk of future hernia incarceration. On

the other hand, it also carries an operative risk of vas

injury, haematoma, and infection of the contralateral

side. In view of the uncertainties about the overall

balance of risks and benefits of routine prophylactic

repair of CPPV, parents should be counselled on the

benefits of avoiding potential future development of

clinical hernia and the risks of the procedure.

Undescended testis (cryptorchidism)

Cryptorchidism has an estimated incidence of 22.8

per 10 000 live births.30 It remains an important

condition because of its potential sequelae of subfertility,

testicular malignancy, and accompanying

inguinal hernia.

Embryology and pathophysiology

Testicular descent is a complex process. Male

differentiation starts at around 7 to 8 weeks of

gestation under the influence of the SRY gene.

Testicular descent involves two phases, the

transabdominal phase and the inguinoscrotal

phase. The gonad descends from the area near the

urogenital ridge to the level of the deep ring in the

transabdominal phase. This phase ends at around

15 weeks of gestation. The inguinoscrotal phase

is a more complex process in which the peritoneal

membrane bulges out and elongates to form the

processus vaginalis through which the testes

then descend. This phase usually starts at around

25 weeks and ends at 35 weeks of gestation. After

descent, the testes will anchor to the connective

tissue within the scrotum.

Both phases of testicular descent are controlled

by hormones. Any derangement in the pathway can

result in cryptorchidism. Conditions known to be

associated with cryptorchidism include prematurity,

Klinefelter syndrome, and abdominal wall defects

like omphalocoele. There is no single cause that

can be identified to account for all the scenarios of

cryptorchidism.

Clinical evaluation

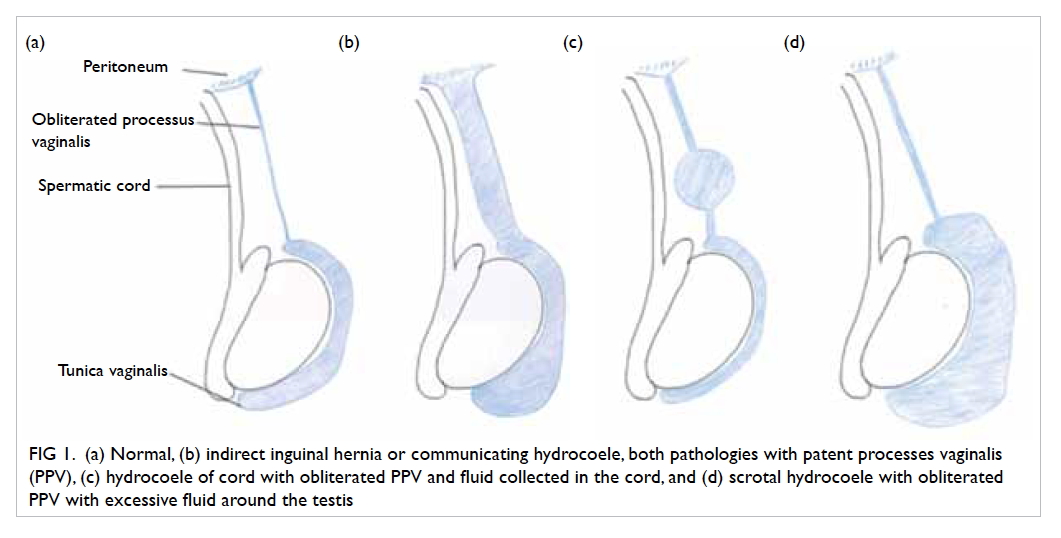

Cryptorchidism is mostly diagnosed by history

and proper clinical examination (Fig 2). As most newborns will undergo a clinical examination before

discharge from hospital, the position of the testes

should be ascertained. During clinical examination,

the infant should be placed supine with legs

abducted in a relaxed and warm environment. A

cold environment may induce a cremasteric reflex

that may move the testes up. Bimanual examination

(two-handed technique) should be performed. The

doctor’s left hand should be placed at the deep ring

and gently sweep along the inguinal canal down to

the scrotum. The right hand should try to detect the

testes at the scrotum or the lowest possible position.

Size, mobility, and consistency of the testes should be

assessed. If there are no palpable testes, a potential

location of ectopic testes should be sought such as the

femoral canal or perineum. The suprapubic region

should be examined as well. Both sides should be

examined carefully with the same technique. Other

concurrent urological anomalies (eg hypospadias)

or problems other than undescended testes (eg

disorder of sexual differentiation) should be checked.

These may warrant further in-depth investigations

or indicate a need for urgent karyotyping in the

newborn period.

A retractile testis should be distinguished from

genuine undescended testis. The clinician should be

able to bring the retractile testis down to the scrotum

and the testis should stay in the scrotum for a while.

It may retract with the cremasteric reflex. Patients

with retractile testes should have normal testicular

volume and fertility. If there is doubt about the

diagnosis, regular assessment or scrotal orchidopexy

can be offered.

Ascending testis is a condition in which the

testis was previously within the scrotum but later

ascends. Presence is usually associated with a history of retractile testis. The postulation is that the

spermatic cord does not elongate with age. These

patients usually present late. A history of previously

noted testicular position should be sought. It has

been shown that ascending testis shares a similar

histopathology to congenital undescended testis.31

Orchidopexy is also recommended.

Investigations

Surgical approach for the undescended testis

differs depending on the location of the testis. The

most important factor is whether or not the testis

is palpable. Clinicians, however, may not be able

to locate the testis during a clinical examination

if the child struggles. If the testis is impalpable,

conditions such as intra-abdominal testis, atrophic

testis, and ectopic testis should also be considered.

Ultrasonography can be used to detect the location

and size of the testis.32 Nijs et al33 noted a high sensitivity of USG scan for inguinal testis but very

low sensitivity for intra-abdominal testis. They

suggested laparoscopic exploration when the testis

cannot be detected on physical examination and

USG.33 34

Use of gadolinium-enhanced magnetic

resonance angiogram was described in 1998 as

another investigation for undescended testes

with high sensitivity and specificity.35 In another

study published in 2000 that compared magnetic

resonance imaging (MRI) with laparoscopy in non-palpable

testes, the false-positive rate of MRI was

32% and true-positive rate for laparoscopy was

100%.36 As MRI is also limited by its costs, availability

and potential need for general anaesthesia in a small

child, many clinicians prefer laparoscopy as the

method of choice for impalpable testis. Nonetheless

there may still be a role for MRI in patients with

suspected persistent Müllerian structures or a

disorder of sexual differentiation.37

Nowadays, early operation on undescended

testis is advocated to reduce the risk of malignancy

and potentially preserve fertility. Early referral

to a surgical specialist may be more important

than investigations. The guideline from American

Urological Association (AUA) published in 2014

advised that health care providers should not

perform USG or other imaging modalities in the

evaluation of boys with cryptorchidism prior to

referral, as these studies rarely assist in decision making

by the general practitioner.38

Treatment

As testicular descent will continue after birth,

watchful waiting should be the initial management

of undescended testes. However, it is advised that all

patients with undescended testis discovered at birth

be re-examined at 6 months of age and referral made

to a specialist if the condition persists.38

A study performed in 1974, which compared

the histology of those with undescended testes

before and after 2 years of age,39 showed loss of

spermatogonia in patients with undescended testis

after 2 years of age. Another study also showed that

the uncorrected position of undescended testes was

associated with ongoing germ cell damage and later

fertility problems and risk of malignancy.40 Thus,

orchidopexy is advised before 18 months of age.

The surgical plan for undescended testes

will be dictated by the position and size of the

testis. For palpable testis in the inguinal canal,

inguinal orchidopexy should be performed. If no

palpable testis can be identified during clinical

examination, adjunct imaging studies in an attempt

to locate the testis can be ordered before surgery.

Laparoscopy, however, remains the gold standard

in diagnosing clinically impalpable testis. In most

cases the testis is located along the line of normal

testicular descent, intra-abdominally or just at

the deep ring of the inguinal canal. Rarely, the

testis can also be atrophic, ectopic, or even absent.

Three approaches have been described for intra-abdominal

testes: primary orchidopexy, one-stage

Fowler-Stephens orchidopexy, or two-stage Fowler-Stephens orchidopexy. Short testicular vessels are

postulated to be the reason why the testis cannot

be brought to the scrotum. The Fowler-Stephens

procedure involves the division of testicular vessels

and repositioning of the testis to the scrotum, either

immediately during the procedure (one-stage) or 6

months later (two-stage). The vascular supply will

depend on the cremasteric vessels and collateral

vessels to the vas after this procedure. Testicular

atrophy and ascent (incidence of both approximately

8%) are potential complications of this procedure.41

On the subject of alternative therapy, the AUA

guideline advises against using hormone therapy

to induce testicular descent as evidence shows low

response rates and a lack of evidence for long-term

efficacy.38

Prognosis/long-term outcome

Patients should be counselled about the increased

risk of testicular malignancy and subfertility.40

A histological study of the undescended testes in

human fetuses, neonates, and infants showed that

the absolute number of germ cells was decreased.42

Mengel et al39 noted a significant decrease in the

content of spermatogonia and a lack of tubular

growth at the beginning of the third year of life. Lee

and Coughlin40 compared paternity rates, the semen

and hormone profiles of patients with previously

unilateral undescended testes, bilateral undescended

testes and normal control subjects; the paternity

rates of these three groups of subjects were 89.7%,

65.3% and 93.2%, respectively. Historical studies

have indicated improved fertility in patients who had

orchidopexy at an earlier age.43

Undescended testis is a known risk factor

for testicular germ cell tumour. In a meta-analysis,

Dieckmann and Pichlmeier44 showed a relative risk

of 4.8 compared with the normal population. The age

at which orchidopexy is performed is also important.

Pettersson et al45 compared the risk of testicular

malignancy between patients who received early

or late orchidopexy and showed the relative risk

of testicular cancer among those who underwent

orchidopexy before reaching 13 years of age was 2.23

(95% confidence interval [CI], 1.58-3.06); for those

treated at 13 years of age or older, the relative risk

was 5.40 (95% CI, 3.20-8.53). It is postulated that the

higher surrounding temperature in undescended

testis could arrest germ cell maturation and become

carcinoma in situ.46

Acute scrotum

Although different disease conditions can present

clinically with acute scrotum, testicular torsion

should be the top differential diagnosis for all

patients, as this condition needs precise clinical

appreciation and urgent management. The time

from presentation to operation is critical and will

determine if the affected testis can be salvaged. A

high index of suspicion with immediate referral is

crucial.

A nationwide epidemiological study in Korea

showed the incidence of testicular torsion was 2.9

per 100 000 person-years of males younger than

25 years, and with a bimodal age distribution with

peak incidence in infancy and adolescents.47 The

salvage rates differ, ranging from 75.7% to 29%.48 49 The diagnosis of torsion depends mostly on

clinical evaluation. Diffuse testicular tenderness,

hydrocoele, high-lying testis with transverse lie, and

absent cremasteric reflex are clinical signs of torsion.

Scrotal exploration should be the management of

choice in clinically suspect cases. As exploration may

be negative, many clinicians have tried adjunctive

methods such as the TWIST (Testicular Workup

for Ischemia and Suspected Torsion) clinical scoring

system,49 Doppler USG, nuclear scintigraphy, MRI,

or evaluation of testicular oxygen saturation with

near-infrared spectroscopy.50 For Doppler USG,

accuracy depends on the skill of the radiologist.

Normal intra-testicular perfusion does not exclude

the possibility of torsion and there remains a false-negative

rate in this modality.51 52 As a missed

diagnosis of testicular torsion is one of the most

common medicolegal claims in adolescent patients

in the United States,53 we must stress again the prime

importance of clinical evaluation and decision.

Nuclear scintigraphy and MRI are not popular for

the same reason. Near-infrared spectroscopy is a

novel technology that measures testicular oxygen

saturation but its accuracy has not been fully

validated in a large population. Scrotal exploration

involves open examination of the affected testes

and a decision on whether to keep or remove the

affected testes and also fix the contralateral side. A

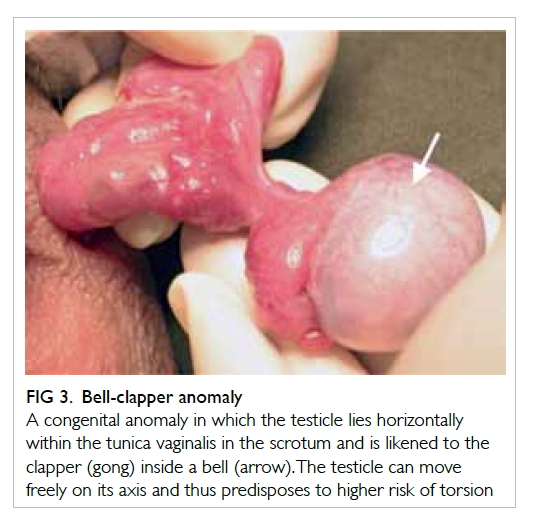

bell-clapper anomaly may be appreciated during

examination of the testes (Fig 3).

Figure 3. Bell-clapper anomaly

A congenital anomaly in which the testicle lies horizontally within the tunica vaginalis in the scrotum and is likened to the clapper (gong) inside a bell (arrow). The testicle can move freely on its axis and thus predisposes to higher risk of torsion

Even after successful testicular salvage,

testicular atrophy has been reported in almost 50%

of patients. Those patients who presented with pain

for more than 1 day were more likely to develop

testicular atrophy. No testes survived in a patient

who presented with pain for more than 3 days.54

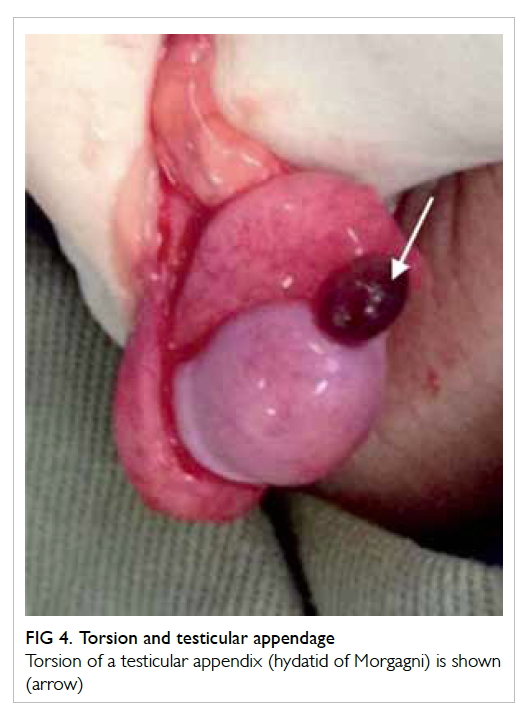

Other causes of acute scrotum include torsion

of the testicular appendage (hydatid of Morgagni),

epididymo-orchitis, idiopathic scrotal oedema,

incarcerated hernia, or Henoch-Schönlein purpura.

Torsion of the testicular appendage presents in a

very similar manner to torsion of the testes (Fig 4).

The patient also complains of intense scrotal pain.

A firm-to-hard pea-sized lesion may be palpable

at the head of the epididymis. The classic ‘blue dot

sign’ may also be appreciated. If testicular torsion

can confidently be excluded, treatment can be by

observation or simple excision of the testicular

appendage. Epididymo-orchitis is a form of urinary

tract infection. In small children or early adolescence,

it may be a presentation of congenital anatomical

urinary tract anomalies.55

Figure 4. Torsion and testicular appendage

Torsion of a testicular appendix (hydatid of Morgagni) is shown (arrow)

Overall we advise general practitioners to seek

urgent referral to a specialist without any delay if

a patient presents with acute scrotum. Operative

exploration should not be delayed by investigations

whenever there is a suspicion of testicular torsion.

Varicocoele

Varicocoele is an abnormal venous dilatation and/or tortuosity of the pampiniform plexus in the

cord. It may present as ‘bags of worms’ clinically

and is identified in 15% of healthy men and up to

35% of men with primary infertility.56 It appears in

adolescent boys, with 7.8% in boys aged 11 to 14

years and 14.1% aged 15 to 19 years.57

Potential clinical problems

Patients may not have any symptoms and can present

late with subfertility. Increased temperature around

the testis is believed to affect spermatogenesis and

endocrine function of the testis.

The World Health Organization stated that

varicocoele was clearly associated with impaired

testicular function and infertility.58 They investigated

34 subfertility centres with 9034 men and identified

varicocoele in 25.4% of men with abnormal semen

compared with 11.7% of men with normal semen.

Comparison of semen analysis in young men

(17-19 years old) with and without varicocoele revealed

significant differences in total and progressive sperm

motility and vitality, which were lower in boys with

varicocoele, and number of normal sperm forms.59

It was concluded that spermatogenesis could be

affected even at this young age.

Clinical evaluation

Clinical (palpable) varicocoele is detected and

graded based on physical examination: a grade 1

varicocoele is one that is only palpable during the

Valsalva manoeuvre; a grade 2 varicocoele is easily

palpable with or without Valsalva but is not visible;

grade 3 refers to a large varicocoele that is easily

palpable and detected on visual inspection of the

scrotum. Size of both testes should be examined and

measured with an orchidometer. Size discrepancy or

testicular atrophy may indicate the need for further

surgical management. Apart from examination

of the genitalia, abdominal examination is also

needed. Any abdominal mass/tumour that causes

compression or obstruction of the renal veins

or gonadal vessels can present with varicocoele.

Ultrasonography of the abdomen and scrotum may

be needed if an abdominal mass is suspected. Semen

analysis may not be practical or necessary in these

child or adolescent patients.

Indications for surgical management

Catch-up growth of the testis after varicocoele

operation has been demonstrated.60 61 Nonetheless the same has also been demonstrated in varicocoele

patients managed conservatively.62 Guidelines or

recommendations have been suggested by different

professional bodies including the AUA, American

Society for Reproductive Medicine, European

Association of Urology, and European Society of

Paediatric Urology (ESPU). These guidelines are

mainly directed to adult patients and there is no

consensus on the indications for surgery. A systematic

review tried to collaborate the opinions from all the

four professional bodies.63 Some agreed indications

include varicocoele with reduced ipsilateral testicular

volume, bilateral varicocoeles, and varicocoele with

pathological semen quality. Symptomatic varicocoele

was suggested as an indication by ESPU but not the

other three associations.

Surgical options and complications

Different open surgical methods have been

described: subinguinal, inguinal (Palomo), and

microsurgical subinguinal approach. All involve

ligation of testicular vessels, with or without the

testicular artery. Laparoscopic high ligation of the

vessels has become popular in this era. Lymphatic or

artery-sparing techniques are preferred by some as

they decrease the postoperative hydrocoele rate.64 65 Radiological embolisation of the testicular vein is

another option.

Recurrence rates vary for different surgical

procedures but are reported to be ranging from 0%

to 35%. The rate of recurrence following various

surgical methods have been quoted as: laparoscopic

(1.2%), non-magnified inguinal (1.3%), open

retroperitoneal (9.3%), microsurgical subinguinal

(0.9%-2.5%), retrograde sclerotherapy (3.6%-8.6%),

and antegrade sclerotherapy (9%).66

Conclusion

Inguinoscrotal pathologies encompass a large

disease spectrum in children. They may have very

similar clinical presentations. Careful history taking

and accurate clinical examination are crucial in

achieving a correct diagnosis resulting in proper and

timely management. There are some points to note:

- A properly performed clinical examination is important in establishing the diagnosis of hydrocoele, inguinal hernia, and undescended testes.

- Clinically evident paediatric inguinal hernia should be offered surgical repair when the patient’s general condition permits general anaesthesia, no matter the age.

- Infantile hydrocoele should be managed with an expectant approach. Parents should be taught to observe for associated inguinal hernia.

- Undescended testis is associated with clinical problems of subfertility, increased risk of testicular torsion, and increased risk of testicular malignancy. Early orchidopexy (<18 months of age) should be advised.

- Testicular torsion is a surgical emergency. Urgent referral to a specialist should be made. Insistent investigations (USG) may confuse the clinical diagnosis and delay surgical management.

- Varicocoele is associated with testicular atrophy and subfertility. Intra-abdominal mass should be excluded. Catch-up growth of the affected testis has been noted in some studies after operation.

References

1. Chan IH, Wong KK. Common urological problems in

children: prepuce, phimosis, and buried penis. Hong Kong

Med J 2016;22:263-9. Crossref

2. Chang SJ, Chen JY, Hsu CK, Chuang FC, Yang SS. The

incidence of inguinal hernia and associated risk factors of

incarceration in pediatric inguinal hernia: a nation-wide

longitudinal population-based study. Hernia 2016;20:559-63. Crossref

3. Kumar VH, Clive J, Rosenkrantz TS, Bourque MD, Hussain

N. Inguinal hernia in preterm infants (≤32-week

gestation). Pediatr Surg Int 2002;18:147-52. Crossref

4. Ein SH, Njere I, Ein A. Six thousand three hundred sixty-one

pediatric inguinal hernias: a 35-year review. J Pediatr

Surg 2006;41:980-6. Crossref

5. Naji H, Ingolfsson I, Isacson D, Svensson JF. Decision

making in the management of hydroceles in infants and

children. Eur J Pediatr 2012;171:807-10. Crossref

6. Koski ME, Makari JH, Adams MC, et al. Infant

communicating hydroceles—do they need immediate

repair or might some clinically resolve? J Pediatr Surg

2010;45:590-3. Crossref

7. Christensen T, Cartwright PC, Devries C, Snow BW. New

onset of hydroceles in boys over 1 year of age. Int J Urol

2006;13:1425-7. Crossref

8. Toki A, Watanabe Y, Sasaki K, et al. Ultrasonographic

diagnosis for potential contralateral inguinal hernia in

children. J Pediatr Surg 2003;38:224-6. Crossref

9. Chen KC, Chu CC, Chou TY, Wu CJ. Ultrasonography for

inguinal hernias in boys. J Pediatr Surg 1998;33:1784-7. Crossref

10. Kaneda H, Furuya T, Sugito K, et al. Preoperative

ultrasonographic evaluation of the contralateral patent

processus vaginalis at the level of the internal inguinal ring

is useful for predicting contralateral inguinal hernias in

children: a prospective analysis. Hernia 2015;19:595-8. Crossref

11. Gholoum S, Baird R, Laberge JM, Puligandla PS.

Incarceration rates in pediatric inguinal hernia: do not

trust the coding. J Pediatr Surg 2010;45:1007-11. Crossref

12. Zamakhshary M, To T, Guan J, Langer JC. Risk of

incarceration of inguinal hernia among infants and young

children awaiting elective surgery. CMAJ 2008;179:1001-5. Crossref

13. Lautz TB, Raval MV, Reynolds M. Does timing matter?

A national perspective on the risk of incarceration in

premature neonates with inguinal hernia. J Pediatr

2011;158:573-7. Crossref

14. Pini Prato A, Rossi V, Mosconi M, et al. Inguinal hernia

in neonates and ex-preterm: complications, timing and

need for routine contralateral exploration. Pediatr Surg Int

2015;31:131-6. Crossref

15. Lee SL, Gleason JM, Sydorak RM. A critical review of

premature infants with inguinal hernias: optimal timing

of repair, incarceration risk, and postoperative apnea. J

Pediatr Surg 2011;46:217-20. Crossref

16. Chan IH, Lau CT, Chung PH, et al. Laparoscopic inguinal

hernia repair in premature neonates: is it safe? Pediatr Surg

Int 2013;29:327-30. Crossref

17. Esposito C, St Peter SD, Escolino M, et al. Laparoscopic

versus open inguinal hernia repair in pediatric patients:

a systematic review. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A

2014;24:811-8. Crossref

18. Schier F, Montupet P, Esposito C. Laparoscopic inguinal

herniorrhaphy in children: a three-center experience with

933 repairs. J Pediatr Surg 2002;37:395-7. Crossref

19. Saka R, Okuyama H, Sasaki T, Nose S, Yoneyama C, Tsukada

R. Laparoscopic treatment of pediatric hydrocele and the

evaluation of the internal inguinal ring. J Laparoendosc

Adv Surg Tech A 2014;24:664-8. Crossref

20. Feng S, Zhao L, Liao Z, Chen X. Open versus laparoscopic

inguinal herniotomy in children: a systematic review and

meta-analysis focusing on postoperative complications.

Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2015;25:275-80. Crossref

21. Chan KL, Hui WC, Tam PK. Prospective randomized

single-center, single-blind comparison of laparoscopic

vs open repair of pediatric inguinal hernia. Surg Endosc

2005;19:927-32. Crossref

22. Celebi S, Uysal AI, Inal FY, Yildiz A. A single-blinded,

randomized comparison of laparoscopic versus open

bilateral hernia repair in boys. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg

Tech A 2014;24:117-21. Crossref

23. Steven M, Carson P, Bell S, Ward R, McHoney M. Simple

purse string laparoscopic versus open hernia repair. J

Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 2016;26:144-7. Crossref

24. Wang Z, Xu L, Chen Z, Yao C, Su Z. Modified single-port

minilaparoscopic extraperitoneal repair for pediatric

hydrocele: a single-center experience with 279 surgeries.

World J Urol 2014;32:1613-8. Crossref

25. Toufique Ehsan M, Ng AT, Chung PH, Chan KL, Wong

KK, Tam PK. Laparoscopic hernioplasties in children: the

implication on contralateral groin exploration for unilateral

inguinal hernias. Pediatr Surg Int 2009;25:759-62. Crossref

26. Wenk K, Sick B, Sasse T, Moehrlen U, Meuli M, Vuille-dit-Bille RN. Incidence of metachronous contralateral

inguinal hernias in children following unilateral repair—A meta-analysis of prospective studies. J Pediatr Surg

2015;50:2147-54. Crossref

27. Hoshino M, Sugito K, Kawashima H, et al. Prediction of

contralateral inguinal hernias in children: a prospective

study of 357 unilateral inguinal hernias. Hernia

2014;18:333-7. Crossref

28. Miltenburg DM, Nuchtern JG, Jaksic T, Kozinetiz C, Brandt

ML. Laparoscopic evaluation of the pediatric inguinal

hernia—a meta-analysis. J Pediatr Surg 1998;33:874-9. Crossref

29. Kokorowski PJ, Wang HH, Routh JC, Hubert KC, Nelson

CP. Evaluation of the contralateral inguinal ring in clinically

unilateral inguinal hernia: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Hernia 2014;18:311-24. Crossref

30. Agopian AJ, Langlois PH, Ramakrishnan A, Canfield MA.

Epidemiologic features of male genital malformations and

subtypes in Texas. Am J Med Genet A 2014;164A:943-9. Crossref

31. Rusnack SL, Wu HY, Huff DS, et al. The ascending testis

and the testis undescended since birth share the same

histopathology. J Urol 2002;168:2590-1. Crossref

32. Kullendorff CM, Hederström E, Forsberg L. Preoperative

ultrasonography of the undescended testis. Scand J Urol

Nephrol 1985;19:13-5. Crossref

33. Nijs SM, Eijsbouts SW, Madern GC, Leyman PM, Lequin

MH, Hazebroek FW. Nonpalpable testes: is there a

relationship between ultrasonographic and operative

findings? Pediatr Radiol 2007;37:374-9. Crossref

34. Shoukry M, Pojak K, Choudhry MS. Cryptorchidism

and the value of ultrasonography. Ann R Coll Surg Engl

2015;97:56-8. Crossref

35. Lam WW, Tam PK, Ai VH, et al. Gadolinium-infusion

magnetic resonance angiogram: a new, noninvasive, and

accurate method of preoperative localization of impalpable

undescended testes. J Pediatr Surg 1998;33:123-6. Crossref

36. Siemer S, Humke U, Uder M, Hildebrandt U, Karadiakos

N, Ziegler M. Diagnosis of nonpalpable testes in

childhood: comparison of magnetic resonance imaging

and laparoscopy in a prospective study. Eur J Pediatr Surg

2000;10:114-8. Crossref

37. Tasian GE, Copp HL, Baskin LS. Diagnostic imaging in

cryptorchidism: utility, indications, and effectiveness. J

Pediatr Surg 2011;46:2406-13. Crossref

38. Kolon TF, Herndon CD, Baker LA, et al. Evaluation and

treatment of cryptorchidism: AUA guideline. J Urol

2014;192:337-45. Crossref

39. Mengel W, Hienz HA, Sippe WG 2nd, Hecker WC. Studies

on cryptorchidism: a comparison of histological findings

in the germinative epithelium before and after the second

year of life. J Pediatr Surg 1974;9:445-50. Crossref

40. Lee PA, Coughlin MT. Fertility after bilateral

cryptorchidism. Evaluation by paternity, hormone, and

semen data. Horm Res 2001;55:28-32.

41. Alagaratnam S, Nathaniel C, Cuckow P, et al. Testicular

outcome following laparoscopic second stage Fowler-Stephens orchidopexy. J Pediatr Urol 2014;10:186-92. Crossref

42. Cortes D, Thorup JM, Beck BL. Quantitative histology of

germ cells in the undescended testes of human fetuses,

neonates and infants. J Urol 1995;154:1188-92. Crossref

43. Hanerhoff BL, Welliver C. Does early orchidopexy improve

fertility? Transl Androl Urol 2014;3:370-6.

44. Dieckmann KP, Pichlmeier U. Clinical epidemiology of

testicular germ cell tumors. World J Urol 2004;22:2-14. Crossref

45. Pettersson A, Richiardi L, Nordenskjold A, Kaijser M,

Akre O. Age at surgery for undescended testis and risk of

testicular cancer. N Engl J Med 2007;356:1835-41. Crossref

46. Hutson JM, Li R, Southwell BR, Petersen BL, Thorup J,

Cortes D. Germ cell development in the postnatal testis:

the key to prevent malignancy in cryptorchidism? Front

Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2013;3:176. Crossref

47. Lee SM, Huh JS, Baek M, et al. A nationwide epidemiological

study of testicular torsion in Korea. J Korean Med Sci

2014;29:1684-7. Crossref

48. Yu Y, Zhang F, An Q, Wang L, Li C, Xu Z. Scrotal

exploration for testicular torsion and testicular appendage

torsion: emergency and reality. Iran J Pediatr 2015;25:e248. Crossref

49. Sheth KR, Keays M, Grimsby GM, et al. Diagnosing

testicular torsion before urological consultation

and imaging: validation of the TWIST score. J Urol

2016;195:1870-6. Crossref

50. Burgu B, Aydogdu O, Huang R, Soygur T, Yaman O, Baker

L. Pilot feasibility study of transscrotal near infrared

spectroscopy in the evaluation of adult acute scrotum. J

Urol 2013;190:124-9. Crossref

51. Kalfa N, Veyrac C, Lopez M, et al. Multicenter assessment

of ultrasound of the spermatic cord in children with acute

scrotum. J Urol 2007;177:297-301. Crossref

52. Lam WW, Yap TL, Jacobsen AS, Teo HJ. Colour Doppler

ultrasonography replacing surgical exploration for acute

scrotum: myth or reality? Pediatr Radiol 2005;35:597-600. Crossref

53. Selbst SM, Friedman MJ, Singh SB. Epidemiology and

etiology of malpractice lawsuits involving children in US

emergency departments and urgent care centers. Pediatr

Emerg Care 2005;21:165-9.

54. Lian BS, Ong CC, Chiang LW, Rai R, Nah SA. Factors

predicting testicular atrophy after testicular salvage

following torsion. Eur J Pediatr Surg 2016;26:17-21. Crossref

55. Redshaw JD, Tran TL, Wallis MC, deVries CR. Epididymitis:

a 21-year retrospective review of presentations to an

outpatient urology clinic. J Urol 2014;192:1203-7. Crossref

56. Alsaikhan B, Alrabeeah K, Delouya G, Zini A. Epidemiology

of varicocele. Asian J Androl 2016;18:179-81. Crossref

57. Akbay E, Cayan S, Doruk E, Duce MN, Bozlu M. The

prevalence of varicocele and varicocele-related testicular

atrophy in Turkish children and adolescents. BJU Int

2000;86:490-3. Crossref

58. World Health Organization. The influence of varicocele on

parameters of fertility in a large group of men presenting to

infertility clinics. Fertil Steril 1992;57:1289-93. Crossref

59. Paduch DA, Niedzielski J. Semen analysis in young men

with varicocele: preliminary study. J Urol 1996;156(2 Pt 2):788-90. Crossref

60. Paduch DA, Niedzielski J. Repair versus observation

in adolescent varicocele: a prospective study. J Urol

1997;158(3 Pt 2):1128-32. Crossref

61. Kass EJ, Belman AB. Reversal of testicular growth failure

by varicocele ligation. J Urol 1987;137:475-6.

62. Preston MA, Carnat T, Flood T, Gaboury I, Leonard MP.

Conservative management of adolescent varicoceles: a

retrospective review. Urology 2008;72:77-80. Crossref

63. Roque M, Esteves SC. A systematic review of clinical

practice guidelines and best practice statements for the

diagnosis and management of varicocele in children and

adolescents. Asian J Androl 2016;18:262-8. Crossref

64. Esposito C, Valla JS, Najmaldin A, et al. Incidence and

management of hydrocele following varicocele surgery in

children. J Urol 2004;171:1271-3. Crossref

65. Chiarenza SF, Giurin I, Costa L, et al. Blue patent

lymphography prevents hydrocele after laparoscopic

varicocelectomy: 10 years of experience. J Laparoendosc

Adv Surg Tech A 2012;22:930-3. Crossref

66. Rotker K, Sigman M. Recurrent varicocele. Asian J Androl

2016;18:229-33. Crossref