DOI: 10.12809/hkmj165045

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

MEDICAL PRACTICE CME

2016 Consensus statement on prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in the

Hong Kong population

Bernard MY Cheung, MB BChir (Cantab), PhD (Cantab)1;

CH Cheng, MB, BS2;

CP Lau, MB, BS, MD3;

Chris KY Wong, MB, ChB (Glasg)4;

Ronald CW Ma, MB BChir (Cantab)5;

Daniel WS Chu, MB, BS (NSW)2;

Duncan HK Ho, MB, BS4;

Kathy LF Lee, MB, BS2;

HF Tse, MD, PhD1;

Alexander SP Wong, MB, BS2;

Bryan PY Yan, MB, BS5;

Victor WT Yan, MB, BS2

1 Department of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Queen Mary

Hospital, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

2 Private practice, Hong Kong

3 Institute of Cardiovascular Science and Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

4 Hong Kong Sanatorium & Hospital, Happy Valley, Hong Kong

5 Department of Medicine and Therapeutics, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Prince of Wales Hospital, Shatin, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Prof Bernard MY Cheung (mycheung@hku.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: In Hong Kong, the prevalence of

atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease has increased

markedly over the past few decades, and further

increases are expected. In 2008, the Hong Kong

Cardiovascular Task Force released a consensus

statement on preventing cardiovascular disease

in the Hong Kong population. The present article

provides an update on these recommendations.

Participants: A multidisciplinary group of clinicians

comprising the Hong Kong Cardiovascular Task

Force—10 cardiologists, an endocrinologist, and a

family physician—met in September 2014 and June

2015 in Hong Kong.

Evidence: Guidelines from the American College

of Cardiology/American Heart Association, the

European Society of Hypertension/European

Society of Cardiology, and the Eighth Joint National

Committee for the Management of High Blood

Pressure were reviewed.

Consensus Process: Group members reviewed

the 2008 Consensus Statement and relevant

international guidelines. At the meetings, each

topical recommendation of the 2008 Statement was

assessed against the pooled recommendations on

that topic from the international guidelines. A final

recommendation on each topic was generated by

consensus after discussion.

Conclusions: It is recommended that a formal risk

scoring system should be used for risk assessment

of all adults aged 40 years or older who have at least

one cardiovascular risk factor. Individuals can be

classified as having a low, moderate, or high risk of

developing atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease,

and appropriate interventions selected accordingly.

Recommended lifestyle modifications include

adopting a healthy eating pattern; maintaining a low

body mass index; quitting smoking; and undertaking

regular, moderate-intensity physical activity.

Pharmacological interventions should be selected as

appropriate after lifestyle modification.

Introduction

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD),

which includes coronary heart disease (CHD),

peripheral vascular disease and stroke, is currently

one of the most common causes of morbidity and

mortality worldwide.1 Unfortunately the prevalence

of ASCVD is expected to increase further over

the next few decades due to a number of factors

including an ageing population and increasing

industrialisation. The latter is associated with

increased exposure to known ASCVD risk factors

such as smoking, low levels of physical activity, and

poor dietary habits such as reduced consumption

of fruit and vegetables and increased fat and salt

intake.2

In Hong Kong, the prevalence of ASCVD risk

factors has increased markedly over the past few

decades. For example, the 2005-2008 Hong Kong

Cardiovascular Risk Factor Prevalence Study-3

(CRISPS-3) reported an 8.6% increase in the

prevalence of abdominal obesity (waist circumference

≥90 cm in men and ≥80 cm in women) and a 21.5%

increase in the prevalence of hypertension among

a cohort of 1803 subjects recruited from CRISPS-1, the first such survey conducted between 1995

and 1996.3 Of the 551 participants of the Hong

Kong Cardiovascular Task Force Risk Management

Programme, 65.4% had hypertension, 63.7%

dyslipidaemia, and 33.3% diabetes at baseline (BMY

Cheung, unpublished data).

Global efforts are underway to promote

ASCVD prevention and reduce the risk of major

ASCVD events. These efforts have yielded benefits—between 1990 and 2013, a substantial reduction in

cardiovascular mortality was seen in central Europe

(5.2%) and western Europe (12.8%), attributed

primarily to birth cohorts’ decreased exposure to

tobacco smoking, improvements in diet, improved

treatment of cardiometabolic risk factors, and

improved treatment of CVD.4

Methods

A multidisciplinary group of clinicians comprising

the Hong Kong Cardiovascular Task Force—10

cardiologists, an endocrinologist, and a family

physician—met in September 2014 and June 2015

in Hong Kong with the aim of updating the first

Consensus Statement on Preventing Cardiovascular

Disease in the Hong Kong Population published

in 2008.5 Prior to the consensus meetings, group

members reviewed the 2008 Consensus Statement

and relevant guidelines from the American College

of Cardiology/American Heart Association, the

European Society of Hypertension/European

Society of Cardiology, and the Eighth Joint National

Committee for the Management of High Blood

Pressure, among others.5 6 7 8 9 At the meetings, each topical recommendation of the 2008 Statement

was assessed against the pooled recommendations

on that topic from the international guidelines

reviewed. A final recommendation on each topic

was generated by consensus after discussion.

The recommendations included in this

consensus statement constitute the consensus

opinion of the members of the Hong Kong

Cardiovascular Task Force regarding the most

appropriate interventions for the Hong Kong

population.

Recommendations

Risk assessment

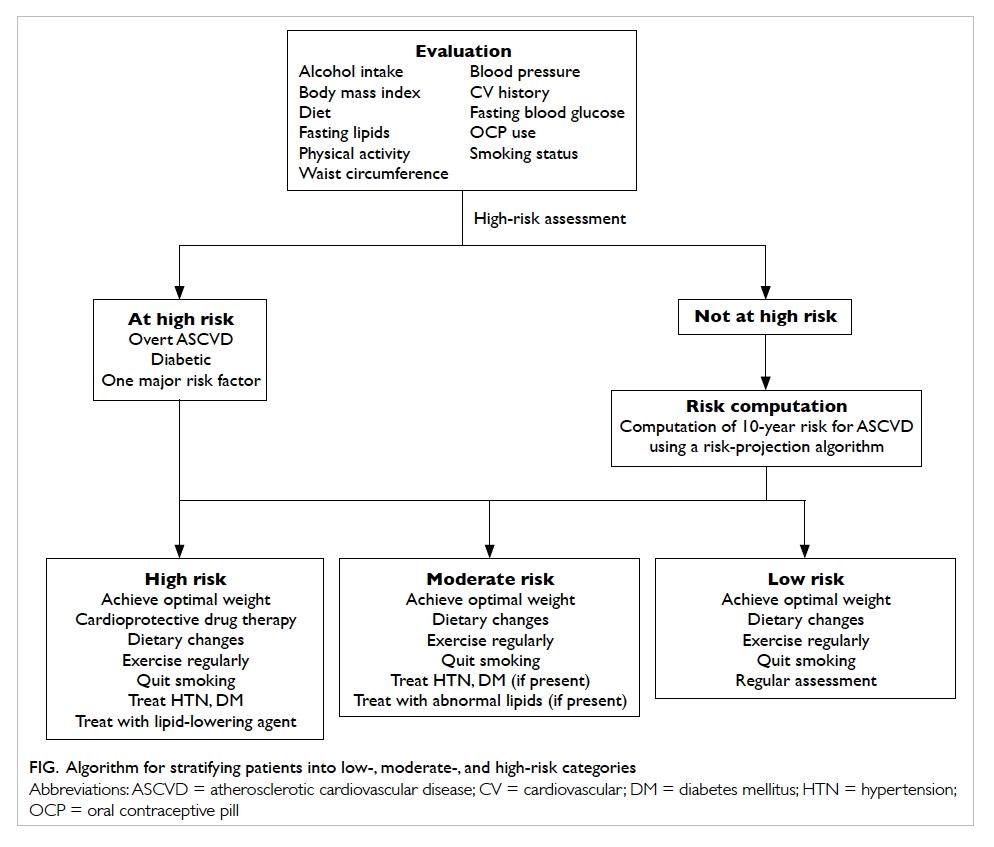

Total cardiovascular risk

Total ASCVD risk is based on the complex

interactions of a number of different risk factors

that together have a multiplicative effect. That is,

the risk of ASCVD is amplified to a greater extent

by the interaction of multiple risk factors than would

be expected due to the cumulative effect of each risk

factor alone.7 9 The present standard of practice for the primary prevention of ASCVD is to determine

a patient’s total ASCVD risk using a formal risk

scoring algorithm.1 7 9

Who to assess?

In Hong Kong, it is recommended that ASCVD

prevention efforts should be focused on adults aged

40 years or older who have at least one ASCVD risk

factor.1 9 The total ASCVD risk should be formally calculated for such individuals, and they should

receive ASCVD prevention advice and/or treatment

according to their determined level of risk (high,

moderate, or low).1 9 High-risk patients will benefit most from treatment and include:

- patients with overt ASCVD (CHD, previous myocardial infarction, previous stroke, or peripheral vascular disease) or those who are symptomatic (eg have experience with angina)

- patients with diabetes mellitus

- patients with one major ASCVD risk factor (eg moderate-to-severe hypertension, severely elevated lipid levels)9

These patients automatically meet the

threshold for intensive risk factor treatment and

need not undergo formal risk scoring.1 9

How to assess?

It is important to note that the current

recommendations do not espouse a preference

for any particular method of risk projection, but

recommend that formal ASCVD risk scoring should

be performed for all potentially at-risk patients.

A patient’s 10-year (total) risk for ASCVD may

be calculated using a variety of methods. The most

recently published algorithm uses the American

Pooled Cohort Risk Assessment Equations that are

sex- and race-specific estimates for African-American

and White men and women aged 40 to 79 years.

They utilise age, total and high-density lipoprotein

(HDL) cholesterol, systolic blood pressure (BP),

diabetes, and current smoking status to calculate

the total ASCVD risk.1 The European Systematic

Coronary Risk Evaluation (SCORE) system is another

well-validated system that uses sex, age, systolic

BP, total cholesterol, and current smoking status

to predict the risk of fatal cardiovascular events.7

Another risk assessment system, QRISK2, includes

the risk factor of ‘self-assigned ethnicity’ (including

Chinese) in the computation10 11; however, the model was validated for Chinese immigrants to the United Kingdom and,

thus, its applicability to the local Chinese population

is unknown.

The calculated risk score is used to stratify

patients into low-, moderate-, and high-risk

categories (Fig). When interpreting these scores,

the clinician should bear in mind that they were

developed and validated for western populations. In

addition, it must be remembered that any calculated

ASCVD score is simply an indicator of total

cardiovascular risk.9 Although it can guide patient

treatment, it cannot be a substitute for individualised

patient evaluation and management. The clinician is

advised to take all factors into account and to treat

the patient individually rather than treat the risk

score.

Risk interventions

There is robust scientific evidence that the

development of ASCVD in at-risk patients

may be slowed and/or prevented by lifestyle

modification, reduction of metabolic risk factors,

and pharmacological treatment.7 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Listed below are

the major modifiable risk factors for ASCVD. The

treatment goal is stated for each risk factor, along with

general recommendations on how this goal may be

achieved. Existing hypertension,7 8 dyslipidaemia,1 6 and diabetes20 21 22 treatment guidelines incorporate

the latest evidence on how to treat these conditions

and to what appropriate targets. The clinician is

referred to these guidelines for further guidance.

Diet

Treatment goal: an overall healthy eating pattern

All patients at increased risk of ASCVD should be

given advice and specific recommendations for

eating a healthy diet. Advice should include9:

- matching energy intake with energy needs;

- eating a variety of fruits, vegetables, grains, low- or non-fat dairy products, legumes, fish, poultry, and lean meats;

- reducing saturated and trans fats to <10% of total daily caloric intake, through replacement with polyunsaturated fats (vegetables, nuts, seeds, and seafood);

- reducing cholesterol intake;

- reducing salt intake; and

- limiting alcohol intake to no more than two drinks per day for men and one drink per day for women.

Physical activity

Treatment goal: a minimum of 30 minutes of

moderate-intensity physical activity at least 5 times

a week, or a minimum of 15 minutes of vigorous-intensity

physical activity at least 5 times a week9

- ‘Moderate intensity’ is defined as exercising at 64% to 76% of maximum heart rate (ie 220 minus age); activities include brisk walking, slow cycling, vacuuming, gardening, golf, tennis (doubles), ballroom dancing, and water aerobics.9 ‘Vigorous intensity’ is defined as exercising at 77% to 93% of maximum heart rate; activities include race walking, jogging or running, bicycling, heavy gardening, swimming laps, and tennis (singles).9

- The practice of the popular Chinese soft martial art tai chi may also be beneficial for individuals at risk of ASCVD. A systematic review has shown that tai chi has physiological and psychosocial benefits, and it also appears to be safe and effective in promoting flexibility, balance control, and cardiovascular fitness in older patients with chronic conditions.23

- All patients should consult their doctor prior to initiating graded exercise programmes.

Overweight/obesity

Treatment goal: maintenance of normal body mass

index and waist circumference

- Normal body mass index is 18.5-22.9 kg/m2 for Asians,24 and normal waist circumference is <90 cm (35.4 inches) for men and <80 cm (31.5 inches) for women.25

- Patients who are overweight or obese should strive to achieve normal body weight by restricting caloric intake and increasing physical activity.

- Drug therapy or surgical interventions may be a helpful adjunct for the treatment of severe obesity in some patients.

Smoking

Treatment goal: complete smoking cessation

- Assess the patient’s tobacco use and strongly urge the patient to stop smoking.

- Determine the patient’s degree of nicotine addiction and his/her readiness to quit smoking. For patients identified as willing to quit, a plan should be developed that may involve pharmacotherapy, counselling, cessation support mechanisms (eg follow-up calls and visits), and referral to specialised programmes, if available.20 26

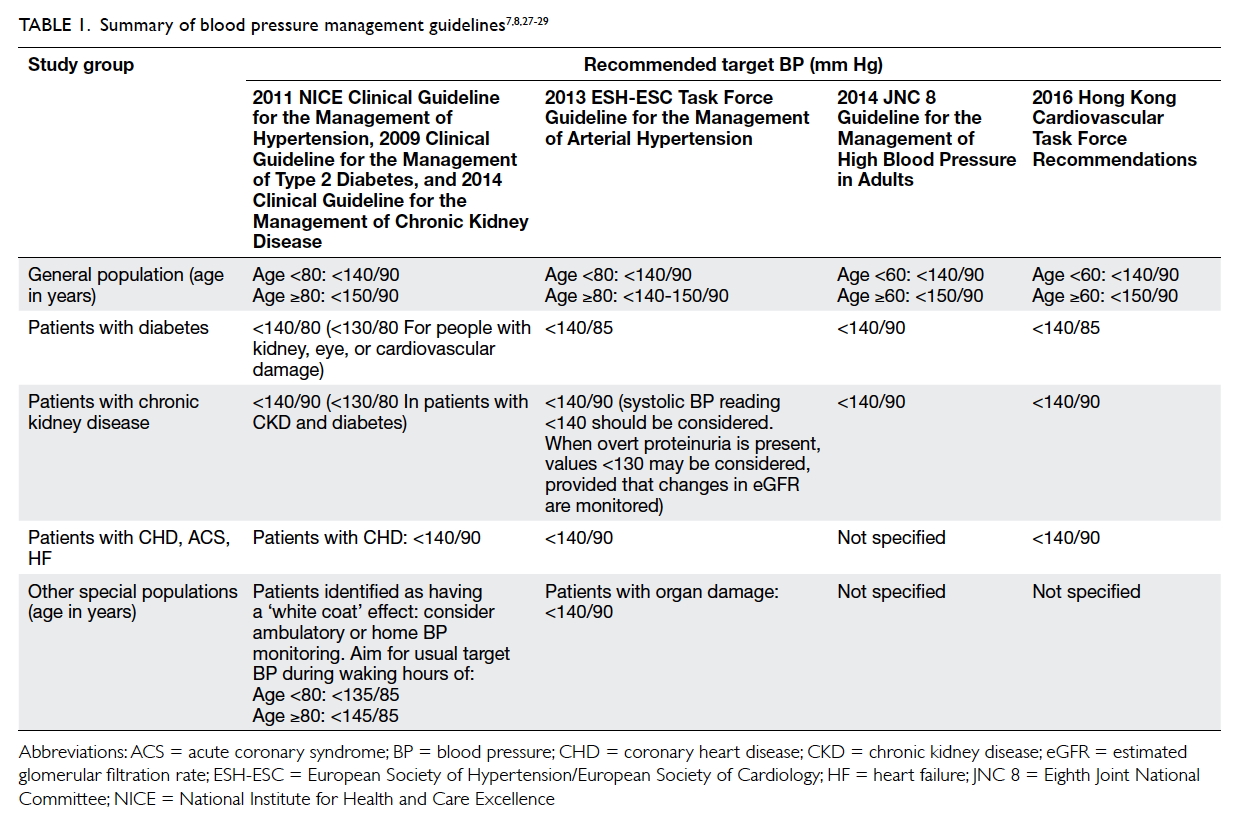

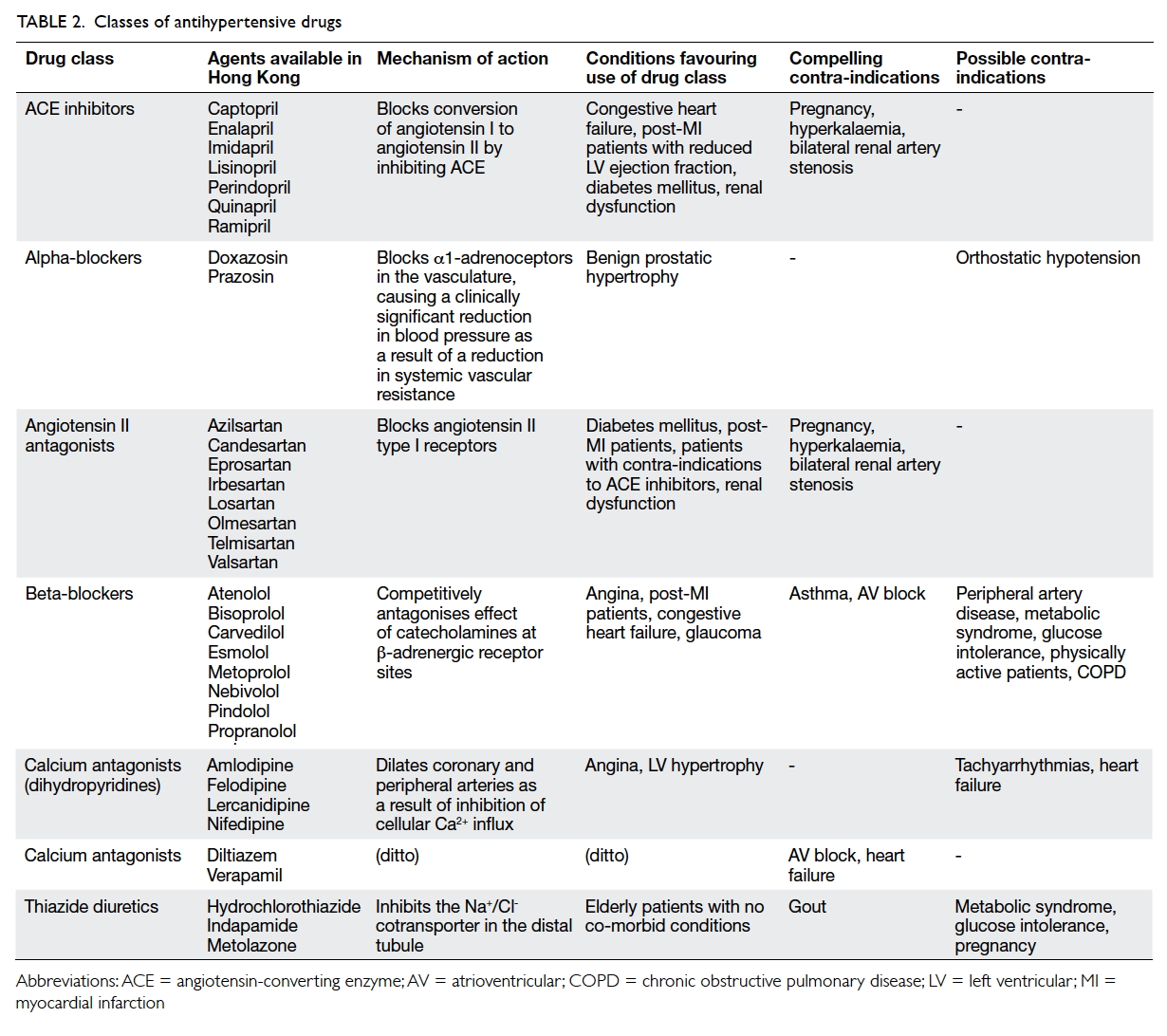

Hypertension

Risk factor reduction goal: blood pressure of <140/90

mm Hg for the general population aged <60 years,

including patients with previous stroke or transient

ischaemic attack; patients with coronary heart disease; and patients with chronic kidney disease.

For patients with diabetes, a target blood pressure

of <140/85 mm Hg is recommended. For the general

population aged ≥60 years, a target blood pressure

of <150/90 mm Hg is recommended7 8 9

- Patients with a systolic BP of ≥130 mm Hg or diastolic BP of ≥80 mm Hg should be given advice and specific recommendations on reducing lifestyle risk factors.

- Patients who do not meet their primary goals as defined above should be given drug therapy tailored to their circumstances.

- The choice of first-line therapy is the prerogative of the attending physician. Suitable antihypertensive drugs include calcium channel blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), either alone or in combination (Tables 1 and 2).7 9 Diuretics (chlorthalidone and indapamide) and β-blockers may also be used, but their long-term use is associated with increased risk of new-onset diabetes30 31; of note, there is no evidence that hydrochlorothiazide—one of the most commonly prescribed antihypertensives—in its usual dose of 12.5 to 25 mg daily reduces myocardial infarction, stroke, or death.32

- When target BP cannot be achieved with monotherapy or with a two-drug combination, doses can be increased; if target BP cannot be achieved by a two-drug combination at full doses, switching to another two-drug combination, or adding a third drug, may be considered.7 8 9 In patients with uncontrolled BP despite treatment with maximally tolerated doses of three antihypertensive medications, addition of the aldosterone antagonist spironolactone has achieved larger reductions in systolic BP than addition of the β-blocker bisoprolol, the alpha-adrenergic blocker doxazosin, or placebo.33

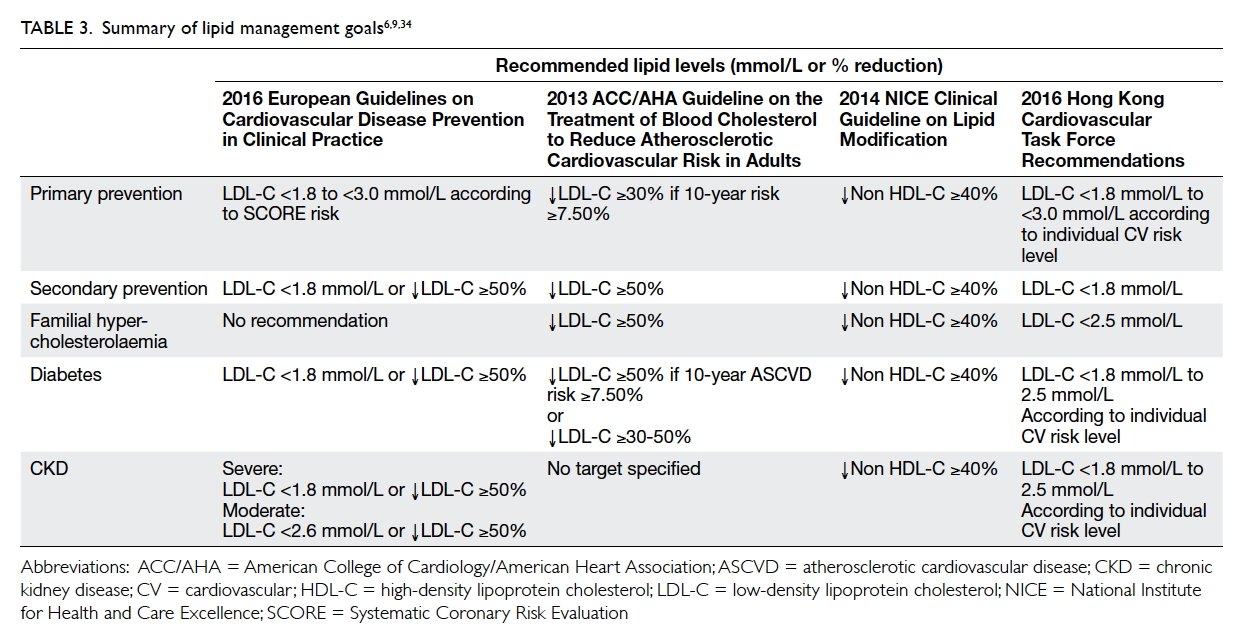

Dyslipidaemia

Risk factor reduction goal: low-density lipoprotein

cholesterol level of <3 mmol/L. For patients with

overt atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, the

target level should be <1.8 mmol/L9

- Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) reduction decreases cardiovascular events.9

- Recommended target LDL-C level for patients stratified by ASCVD risk is as follows:

- Very high ASCVD risk: LDL-C <1.8 mmol/L, or a ≥50% reduction if the baseline is between 1.8 and 3.5 mmol/L (Table 3)

- High ASCVD risk: LDL-C <2.6 mmol/L, or a ≥50% reduction if the baseline is between 2.6 and 5.1 mmol/L

- Low-to-moderate ASCVD risk: LDL-C <3.0 mmol/L9

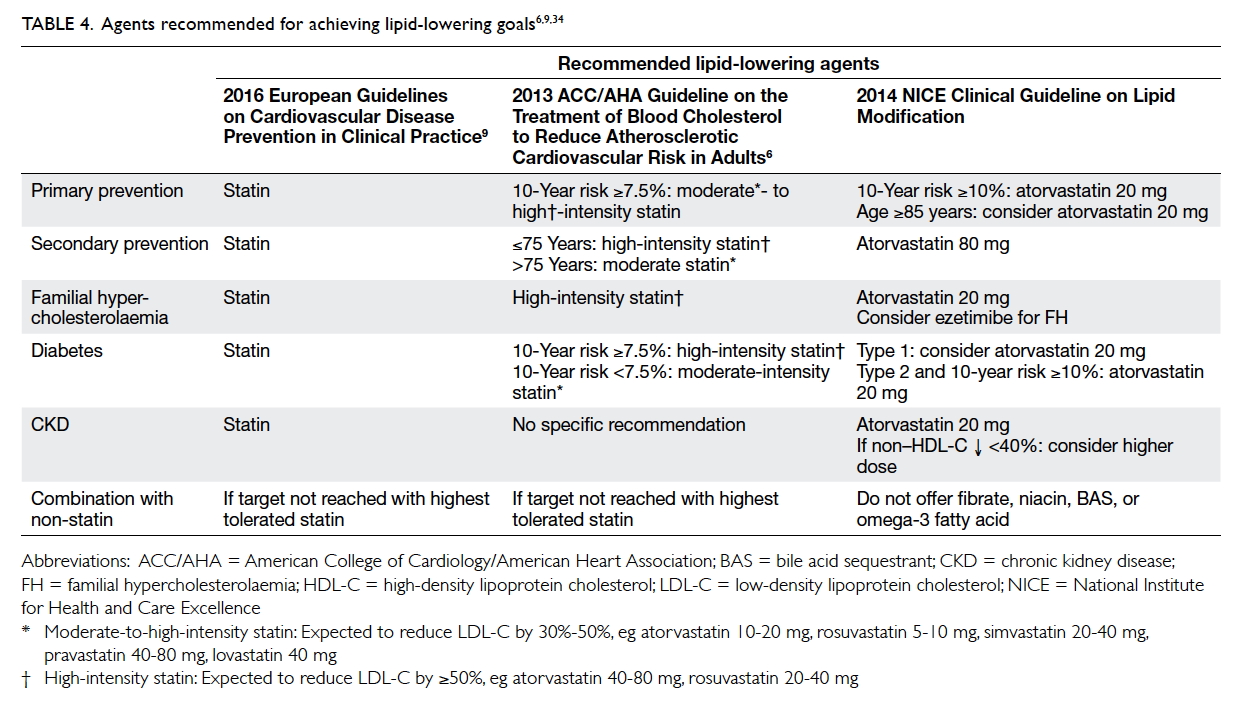

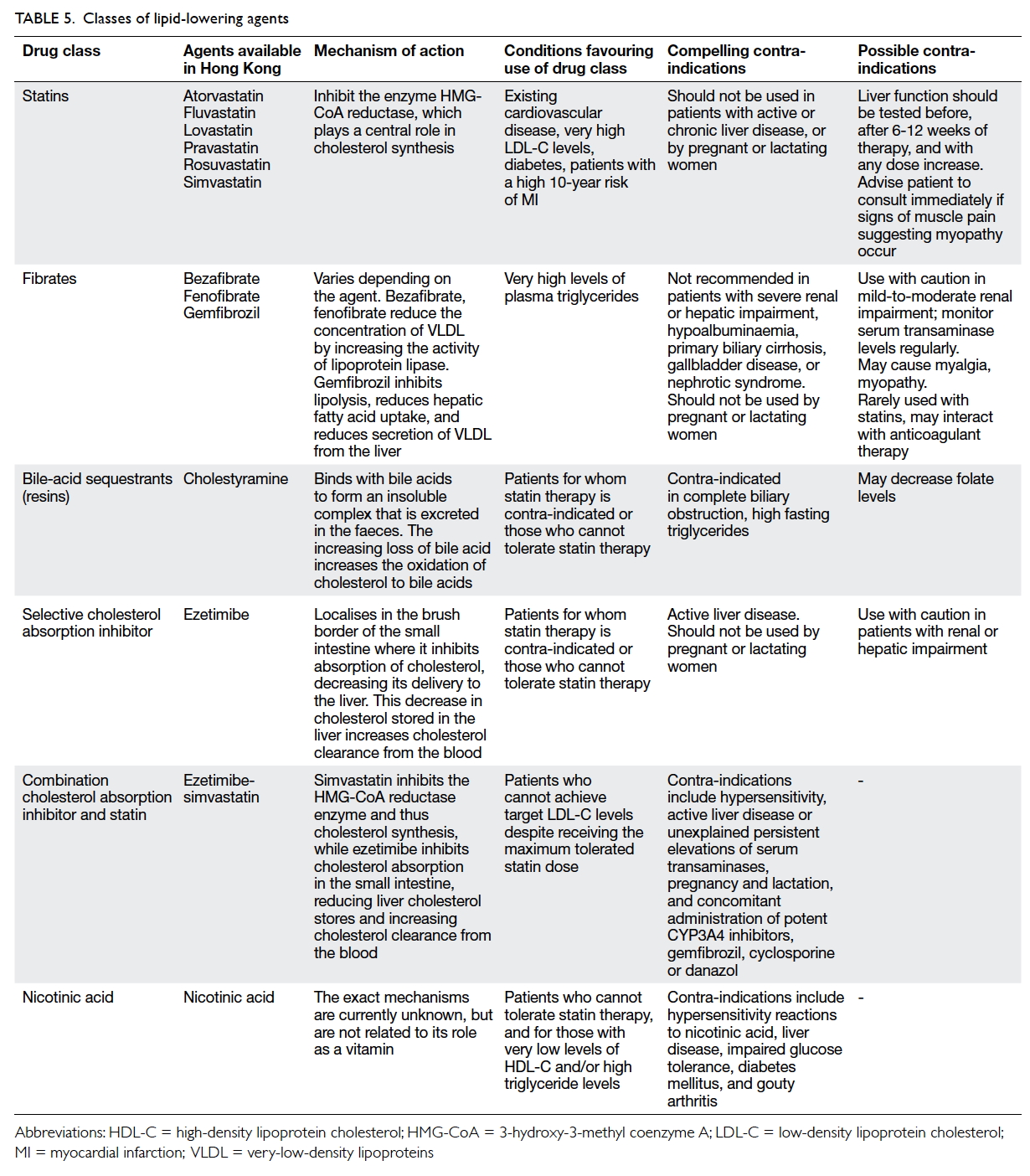

- Patients at low and moderate risk should be given advice and specific recommendations on lowering LDL-C through dietary adjustments, increased physical activity, and weight reduction. If the target is not met after 6 months, they should be given a lipid-lowering agent (Tables 4 and 5).35

- Patients at high risk should immediately be started on lipid-lowering therapy with a high-intensity statin (Tables 4 and 5).35 Importantly, however, pharmacokinetic studies have shown that Chinese patients achieve a higher plasma concentration of statin compared with Caucasians, and this may be associated with an increased risk of adverse effects.36 Consequently, the maximum approved doses of the statins available in Asia are around half the maximum approved doses in the United States.37 The clinician should, therefore, exercise caution when prescribing high-intensity statin therapy.

- Inhibitors of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 have recently been approved for use in the United Kingdom and the United States as an adjunct to diet and maximally tolerated statin therapy for the treatment of individuals with primary hypercholesterolaemia or mixed dyslipidaemia, or those with clinical ASCVD who require additional lowering of LDL-C.38 39 Clinical trials have demonstrated decreases in LDL-C by up to 60% in subjects receiving these agents38; definitive evidence of reduced cardiovascular event rates associated with their use may be provided by ongoing trials.

Diabetes

- All diabetic patients are considered high risk for the development of ASCVD9 21 and should receive appropriate management upon diagnosis. This includes guidance on diet modification and increased physical activity in conjunction with pharmacotherapy.20 21 22 Early initiation of medication is recommended to avoid any delay in treatment. Insulin is administered if treatment goals are not achieved with oral therapy.20 21 22 Treatment goal for glycaemia should be tailored according to the patient profile in order to avoid hypoglycaemia in those with co-morbidities or in elderly patients.22 40

- In diabetic patients, treat other ASCVD risk factors more aggressively,22 including hypertension. Nevertheless, present evidence suggests that a BP target of <140/85 mm Hg is appropriate in patients with diabetes, with a lower BP (systolic BP of <130 mm Hg) as an option in patients with hypertension and nephropathy. It should be noted that lower BP may be associated with increased risk of adverse events, especially in older patients or those with a long duration of diabetes, and the risk and benefit of intensive BP lowering needs to be considered individually according to the patient profile.22

Discussion

The gap between evidence and practice

Although clear, evidence-based guidelines and

recommendations for ASCVD prevention have

been available for a number of years and are

regularly updated, there is evidence that they are

not routinely implemented in clinical practice.9 41 42

For example, Yusuf et al43 reported worldwide poor

use of medications for the secondary prevention of

ASCVD. Their study included 153 996 adults aged

35 to 70 years from rural and urban communities

in high-, upper-middle–, lower-middle–, and

low-income countries, 5650 of whom had had a

self-reported CHD event and 2292 a stroke. Few

individuals with ASCVD took antiplatelet drugs

(25.3%), β-blockers (17.4%), ACE inhibitors or ARBs

(19.5%), or statins (14.6%). As expected, drug use

was higher in high-income countries, with 11.2% of

patients in these countries not receiving any drugs

compared with 45.1% of patients in upper-middle–income

countries, 69.3% in lower-middle–income

countries, and 80.2% in low-income countries.

Notably, despite the relative accessibility of drugs

for secondary prevention of ASCVD in high- and

upper-middle–income countries, many patients

remained untreated.

Of the patients who do receive treatment for

ASCVD risk factors, only a few attain their treatment

goals. Findings from the Hong Kong Cardiovascular

Task Force Risk Management Programme indicate

that 84% of enrolled hypertensive patients were

treated with one or two antihypertensive drugs,

most commonly ARBs (63.5%) and calcium channel

blockers (47.2%; BMY Cheung, unpublished data).

Similarly 64% of the diabetic patients were treated

with metformin (68.8%) and/or gliptins (36%), while

78.1% of patients with dyslipidaemia were treated

with a statin. Notably, however, treatment goals for

hypertension (<130/80 mm Hg for diabetic patients,

<140/90 mm Hg for non-diabetics) and diabetes

(glycated haemoglobin <7%) were met by just over

50% of hypertensive patients and approximately 60%

of diabetics.

Ensuring physician compliance with

evidence-based guidelines and improving clinician

understanding of factors affecting patient compliance

with treatment may be the key to decreasing ASCVD

risk in the Hong Kong population.

Differences between the 2008 and 2016

consensus statements

The present update of the 2008 Consensus

Statement introduces the use of the new American

Pooled Cohort Risk Assessment Equations that

have superseded the Framingham Risk Evaluation;

ASCVD risk can be assessed using either these

equations or the European SCORE system to

stratify patients into low-, moderate-, or high-risk

categories to aid targeting of therapies as well as

the establishment of suitable treatment goals. The

risk factor reduction goals for hypertension and

dyslipidaemia have been updated to reflect the

most current recommendations from the Eighth

Joint National Committee, the European guidelines

on the management of arterial hypertension, and

the European guidelines on cardiovascular disease

prevention in clinical practice. The HDL-C target

included in the 2008 Consensus Statement has

been omitted from the current update as increased

HDL-C has not been proven to reduce ASCVD risk.

Conclusions

The development of ASCVD in at-risk patients

may be slowed and/or prevented by lifestyle

modification, reduction of metabolic risk factors,

and pharmacological treatment. The clinician plays

a central role in ASCVD prevention—identifying

at-risk patients, calculating the total ASVCD risk

score, encouraging lifestyle changes, and providing

targeted interventions to achieve specific treatment

goals. Nonetheless, it is vital that the clinician is not

overly focused on the treatment of isolated ASCVD

risk factors but should instead adopt a ‘whole-person’

approach to diagnosis and therapy. Many

patients present with multiple risk factors and,

therefore, individualised, nuanced patient evaluation

and management is essential to achieve optimum

outcomes. Finally, none of these interventions will

result in ASVCD prevention without the cooperation

of the patient. Clinicians are encouraged to build

strong partnerships with their patients, with the

aim of establishing individual ownership of their

treatment plans and, thus, improved treatment

compliance.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Ms Lianne

Cowie and Dr Jose Miguel (Awi) Curameng of

MIMS (Hong Kong) Limited for providing editorial

and writing support, which was funded by Pfizer

Corporation Hong Kong Limited. The meetings

during which these consensus points were formulated

and discussed were supported by an unrestricted

educational grant from Pfizer Corporation Hong

Kong Limited.

Declaration

Source of support: Editorial and writing services, and

the meetings during which these consensus points

were formulated and discussed, were supported

by an unrestricted educational grant from Pfizer

Corporation Hong Kong Limited.

References

1. Goff DC Jr, Lloyd-Jones DM, Bennett G, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American

Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines.

Circulation 2014;129(25 Suppl 2):S49-73. Crossref

2. Yusuf S, Reddy S, Ounpuu S, Anand S. Global burden of

cardiovascular diseases. Part I: general considerations,

the epidemiologic transition, risk factors, and impact of

urbanization. Circulation 2001;104:2746-53. Crossref

3. Cheung MY, Ong KL, Tso WK, Lam TH, Lam SL. Increasing

prevalence of hypertension in Hong Kong Cardiovascular

Risk Factor Prevalence Study: role of general and central

obesity. Proceedings of the 16th Medical Research

Conference; 2011 Jan 22; Department of Medicine, The

University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J

2011;17(Suppl 1):16S.

4. Roth GA, Huffman MD, Moran AE, et al. Global and

regional patterns in cardiovascular mortality from 1990 to

2013. Circulation 2015;132:1667-78. Crossref

5. Cheung MY, Chow CC, Chu DW, et al. The Hong Kong

Cardiovascular Task Force. Towards cardiovascular

disease protection. Consensus statement on preventing

cardiovascular disease in the Hong Kong population. Med

Prog 2008;35:473-9.

6. Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to

reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a

report of the American College of Cardiology/American

Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am

Coll Cardiol 2014;63(25 Pt B):2889-934. Crossref

7. Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, et al. 2013 ESH/ESC

guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the

Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension

of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of

the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J

2013;34:2159-219. Crossref

8. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 Evidence-based

guideline for the management of high blood pressure

in adults: report from the panel members appointed to

the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA

2014;311:507-20. Crossref

9. Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, Agewall S, et al. 2016 European

guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in

clinical practice: The Sixth Joint Task Force of the

European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on

Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice

(constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by

invited experts) developed with the special contribution of

the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention &

Rehabilitation (EACPR). Eur Heart J 2016;37:2315-81. Crossref

10. Collins GS, Altman DG. Predicting the 10 year risk of

cardiovascular disease in the United Kingdom: independent

and external validation of an updated version of QRISK2.

BMJ 2012;344:e4181. Crossref

11. QRISK2. Available from: https://www.qrisk.org/2016/.

Accessed 9 Jan 2017.

12. Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Group. Randomized

trial of cholesterol lowering in 4,444 patients with coronary

heart disease: the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study

(4S). Lancet 1994;344:1383-9.

13. Shepherd J, Cobbe SM, Ford I, et al. Prevention of

coronary heart disease with pravastatin in men with

hypercholesterolemia. West of Scotland Coronary

Prevention Study Group. N Engl J Med 1995;333:1301-7. Crossref

14. Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or

insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of

complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33).

UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Lancet

1998;352:837-53. Crossref

15. Retinopathy and nephropathy in patients with type 1

diabetes four years after a trial of intensive therapy. The

Diabetes Control and Complications Trial/Epidemiology

of Diabetes Interventions and Complications Research

Group. N Engl J Med 2000;342:381-9. Crossref

16. Antithrombotic Trialists’ Collaboration. Collaborative

meta-analysis of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy

for prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke

in high risk patients. BMJ 2002;324:71-86. Crossref

17. US Department of Health and Human Services. The

health benefits of smoking cessation. Washington DC: US

Department of Health and Human Services; 1990.

18. Taylor R, Brown A, Ebrahim S, et al. Exercise-based

rehabilitation for patients with coronary heart disease:

systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized

controlled trials. Am J Med 2004;116:682-92. Crossref

19. Prevention of cardiovascular disease. Guidelines for

assessment and management of cardiovascular risk.

Geneva, World Health Organization; 2007.

20. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care

in diabetes—2014. Diabetes Care 2014;37(Suppl 1):S14-80. Crossref

21. The Hong Kong reference framework for diabetes care

for adults in primary care settings. Available from: http://www.pco.gov.hk/english/resource/files/RF_DM_full.pdf.

Accessed 1 Dec 2014.

22. Rydén L, Grant PJ, Anker SD, et al. ESC guidelines on

diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases

developed in collaboration with the EASD: the Task Force

on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases of

the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and developed

in collaboration with the European Association for the

Study of Diabetes (EASD). Eur Heart J 2013;34:3035-87. Crossref

23. Wang C, Collet JP, Lau J. The effect of Tai Chi on health

outcomes in patients with chronic conditions: a systematic

review. Arch Intern Med 2004;164:493-501. Crossref

24. WHO Expert Consultation. Appropriate body-mass index

for Asian populations and its implications for policy and

intervention strategies. Lancet 2004;363:157-63. Crossref

25. International Diabetes Federation. The IDF consensus

worldwide definition of the metabolic syndrome. Available

from: http://www.idf.org/webdata/docs/MetSyndrome_FINAL.pdf. Accessed 10 Jul 2015.

26. West R, McNeill A, Raw M. Smoking cessation guidelines

for health professionals: an update. Health Education

Authority. Thorax 2000;55:987-99. Crossref

27. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Hypertension in adults: diagnosis and management. NICE guideline (CG127). August 2011. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg127. Accessed 10 Jul 2015.

28. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Type 2 diabetes: The management of type 2 diabetes. NICE guideline (CG87). May 2009. Accessed 10 Jul 2015.

29. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Chronic kidney disease in adults: assessment and management. NICE guideline (CG182). July 2014. Accessed 10 Jul 2015.

30. Shen L, Shah BR, Reyes EM, et al. Role of diuretics, β

blockers, and statins in increasing the risk of diabetes in

patients with impaired glucose tolerance: reanalysis of data

from the NAVIGATOR study. BMJ 2013;347:f6745. Crossref

31. Bangalore S, Parkar S, Grossman E, Messerli FH. A meta-analysis

of 94,492 patients with hypertension treated with

beta blockers to determine the risk of new-onset diabetes

mellitus. Am J Cardiol 2007;100:1254-62. Crossref

32. Messerli FH, Bangalore S. Half a century of

hydrochlorothiazide: facts, fads, fiction, and follies. Am J

Med 2011;124:896-9. Crossref

33. Williams B, MacDonald TM, Morant S, et al. Spironolactone

versus placebo, bisoprolol, and doxazosin to determine

the optimal treatment for drug-resistant hypertension

(PATHWAY-2): a randomised, double-blind, crossover

trial. Lancet 2015;386:2059-68. Crossref

34. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Cardiovascular disease: risk assessment and reduction, including lipid modification. NICE guideline (CG181). July 2014. Accessed 10 Jul 2015.

35. Baigent C, Keech A, Kearney PM, et al. Efficacy and safety

of cholesterol-lowering treatment: prospective meta-analysis

of data from 90 056 participants in 14 randomised

trials of statins. Lancet 2005;366:1267-78. Crossref

36. Tomlinson B, Hu M, Zhang Y, Liu ZM, Chan P. Response to

the letter “No evidence to support high-intensity statin in

Chinese patients with coronary heart disease”. Int J Cardiol

2016;209:192-3. Crossref

37. Liao JK. Safety and efficacy of statins in Asians. Am J

Cardiol 2007;99:410-4. Crossref

38. Everett BM, Smith RJ, Hiatt WR. Reducing LDL with

PCSK9 inhibitors—the clinical benefit of lipid drugs. N

Engl J Med 2015;373:1588-91. Crossref

39. Mayor S. NICE recommends PCSK9 inhibitors for patients

not responding to statins. BMJ 2016;353:i2609. Crossref

40. Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al. Management of

hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2015: a patient-centered

approach: update to a position statement of the American

Diabetes Association and the European Association for the

Study of Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2015;38:140-9. Crossref

41. Ma J, Sehgal NL, Ayanian JZ, Stafford RS. National trends

in statin use by coronary heart disease risk category. PLoS

Med 2005;2:e123. Crossref

42. Pearson TA. The prevention of cardiovascular disease:

have we really made progress? Health Aff (Millwood)

2007;26:49-60. Crossref

43. Yusuf S, Islam S, Chow CK, et al. Use of secondary prevention

drugs for cardiovascular disease in the community in high-income,

middle-income, and low-income countries (the

PURE Study): a prospective epidemiological survey. Lancet

2011;378:1231-43. Crossref