Hong Kong Med J 2017 Feb;23(1):28–34 | Epub 14 Dec 2016

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj164887

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

The pattern of cervical smear abnormalities in marginalised women in Hong Kong

YH Ting, FRCOG, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)1;

HY Tse, FRCOG, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)2;

WC Lam, MPH (CUHK), FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)3;

KS Chan, FRCOG, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)4;

TY Leung, LMCHK; DCOGHK5

1 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Prince of Wales Hospital, Shatin, Hong Kong

2 Magnus MRI and Ultrasound Diagnostic Center, Hermes Commercial

Centre, Tsimshatsui, Hong Kong

3 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Tseung Kwan O Hospital,

Tseung Kwan O, Hong Kong

4 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Kwong Wah Hospital,

Yaumatei, Hong Kong

5 Well Women Clinic, Tung Wah Group of Hospitals, Yaumatei, Hong Kong

An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 29th International Congress of the Medical Women’s International Association held in Ewha Woman’s University, Seoul, Korea on 31 July to 3 August 2013.

Corresponding author: Dr YH Ting (tingyh@cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: “Ripple Action” and “WE Stand” are

projects co-organised by the Hong Kong Women

Doctors Association. The two projects organise

free cervical screening for low-income women,

new immigrants from Mainland China, and ethnic

minority women. The objective of this study was to

analyse the pattern of cervical smear abnormalities

in these marginalised women.

Methods: The study group consisted of 1189

marginalised women who participated in a free

cervical screening campaign, including 324 low-income

local Chinese, 540 new immigrants from

Mainland China, and 325 ethnic minority women.

The comparison group consisted of 1141 local

Chinese who attended a well women clinic. The

prevalence of cervical smear abnormalities was

compared using Chi squared test.

Results: In the study group, 42.6% of women had

never had a cervical smear. Compared with the

comparison group, they had a significantly higher

prevalence of cervical smear abnormalities (13.7%

vs 1.4%; P<0.001), including atypical smear (10.8%

vs 0.5%; P<0.001), low-grade lesion (1.8% vs 0.8%;

P=0.036), and high-grade lesion (1.1% vs 0.1%;

P=0.002). Logistic regression analysis showed that

the strongest predictors for abnormal cervical

smear were being South Asian (odds ratio=11.859;

95% confidence interval, 4.635-30.341), South-East

Asian (6.484; 3.192-13.171), or new immigrant from

Mainland China (6.253; 2.463-15.877).

Conclusions: Marginalised women had a

significantly higher prevalence of cervical smear

abnormality than the general population and almost

half had never had a cervical smear before. Outreach

strategies are needed to enrol this population into

screening programmes.

New knowledge added by this study

- Of the marginalised women studied, 42.6% have never had a cervical smear.

- Marginalised women have a significantly higher prevalence of cervical smear abnormality than the general population.

- South Asian, South-East Asian, and new immigrants from Mainland China have a 6- to 11-fold increased risk of cervical smear abnormalities compared with the local Chinese population.

- The Government should be proactive in developing a more comprehensive cervical cancer screening programme in Hong Kong.

- The Government should ensure adequate cervical cancer screening coverage for marginalised women in Hong Kong by developing community outreach programmes through collaboration with non-governmental organisations in the community.

Introduction

Cervical cancer is an important global health problem

in women. It is the fourth most common cancer in

women worldwide with an age-standardised rate

(ASR) of 14.2 per 100 000.1 Cervical screening and

treatment of precancerous lesions have been shown

to reduce the incidence and mortality of cervical

cancer in many developed countries. This remarkable

success has been achieved through organised

screening programmes. Such programmes, however,

are not routinely available in most developing

countries.2 3

Cervical cancer screening in Hong Kong

An organised cervical cancer screening programme

was launched in Hong Kong in 2004 for 25- to

64-year-old women who were currently or previously

had been sexually active.4 The programme does

not proactively recruit eligible women who have

never had a cervical smear. These women must

seek cervical smear services by themselves from

family health service clinics, well women clinics,

general practitioners, or private gynaecologists

for their first smear before they can be registered

under the programme and become eligible for

recall for subsequent smears. Of eligible women in

Hong Kong, 30% have yet to have a cervical smear,

despite the availability of the scheme for 11 years.5

The most common reasons cited were cost, lack of

time, ignorance about cervical cancer and screening,

lack of knowledge about how to access the screening

service, and embarrassment.6 7 8 9 These reasons were

particularly common for marginalised women.

‘Ripple Action’ and ‘WE Stand’

‘Ripple Action’ is a collaborative project launched

by several women professional bodies to serve the

marginalised women in Hong Kong. Collaborating

parties include doctors, nurses, lawyers, accountants,

social workers, and various local women

organisations. ‘WE Stand’ is a project launched

by RainLily in collaboration with the Hong Kong

Women Doctors Association to raise the awareness

about sexual violence against foreign female workers

and ethnic minority women. These two projects

organise free cervical screening events for low-income

women, new immigrants from Mainland

China, and ethnic minority women. The objective

of this study was to analyse the pattern of cervical

smear abnormalities in these marginalised women.

Methods

The study group consisted of women who had a

cervical smear taken in one of the 16 free cervical

screening events held between March 2008 and

November 2014. These women were recruited by

various charitable non-governmental organisations

(NGOs) and included low-income local Chinese

women in receipt of assistance from NGOs, new

immigrants from Mainland China who had lived

in Hong Kong for less than 7 years, and ethnic

minority women mainly from South Asia and South-East Asia. Demographic data, including age, self-reported

ethnicity, date of last menstrual period, and

history of cervical smear were recorded.

Menstruating women and those with a hysterectomy

or no sexual history were excluded from screening.

Informed consent for cervical smear taking was

obtained. Cervical smears were processed using

the ThinPrep Pap Test liquid-based system in an

accredited cytology laboratory and examined by

accredited cytopathologists at a private hospital. All

cervical smear reports were reviewed by specialist

gynaecologists. Women with a normal cervical

smear were called to collect the report in person

from the referring NGO. Women with a cervical

smear abnormality were individually counselled

by a specialist gynaecologist. Women with atypical

smears were referred to a family health service clinic

for a follow-up smear. Women with epithelial lesions

were referred to the gynaecology department in a

public hospital.

The prevalence of cervical smear abnormalities

in the study group was compared with a comparison

group that comprised cervical smear reports selected

from the database of a well women clinic in Hong

Kong. The first 200 of every 1000 sequential smear

reports taken in the four Februarys of the years 2011

to 2014 were selected. To ensure that these reports

were from local Chinese population, reports bearing

foreign names and those with the first alphabet of

the identity card number being R (holders arrived

Hong Kong from 2000 to 2011), M (holders arrived

after 2011), or W (foreign workers) were excluded.

Unsatisfactory smears and vault smears were also

excluded. Statistical analysis of the difference in the

prevalence of cervical smear abnormalities between

the study and the comparison groups was performed

with Chi squared test using the Statistical Package for

the Social Sciences (Windows version 22.0; SPSS

Inc, Chicago [IL], US). A P value of <0.05 was

regarded as statistically significant. Binary logistic

regression analysis was performed to predict the

odds of having a cervical smear abnormality using

the following variables: (1) age; (2) resident in Hong

Kong for less than 7 years; (3) never had a cervical

smear before; (4) ethnicity including local Chinese

(reference group), new immigrant from Mainland

China, South-East Asian (Indonesian, Filipino, and

Thai) or South Asian (Indian, Pakistani, Sri Lankan,

Nepalese, and Bangladeshi). The study was approved

by the Joint Chinese University of Hong Kong–New

Territories East Cluster Clinical Research Ethics

Committee (CREC Ref. No.: 2015.426).

Results

There were 1194 participants across the 16 free

cervical screening events. Five women were excluded

from cervical smear screening because of previous

hysterectomy or current menstruation. Thus, the

study group consisted of 1189 marginalised women,

including 324 low-income local Chinese women

who were receiving assistance from NGOs, 540

new immigrants from Mainland China who were

residents in Hong Kong for less than 7 years, and

325 ethnic minority women mainly from South Asia

and South-East Asia. The characteristics of the study

group, including the self-reported ethnicity, history

of cervical smear, and prevalence of cervical

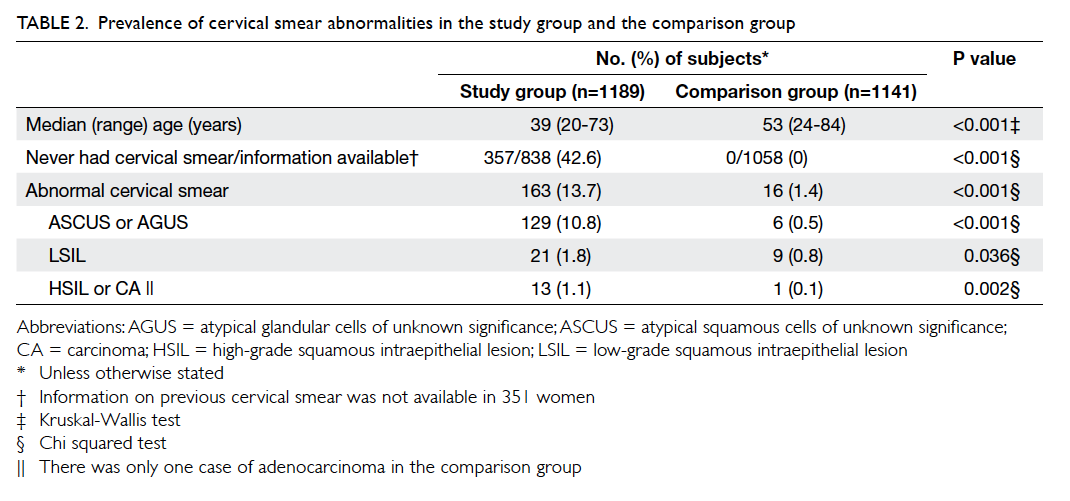

smear abnormalities are shown in Table 1. Among

the 838 women with information available about a history of cervical smear, 357 (42.6%) had

never had a cervical smear. Compared with the local

Chinese in the study group, there were significantly

more ethnic minority women and new immigrants

from Mainland China who had never had a cervical

smear (61.2% vs 45.4% vs 25.0%; P<0.001), and their

prevalence of cervical smear abnormalities was also

significantly higher (20.0% vs 12.8% vs 9.0%; P<0.001)

[Table 1].

Table 1. Characteristics of the 1189 participants of the free cervical screening campaign according to ethnicity

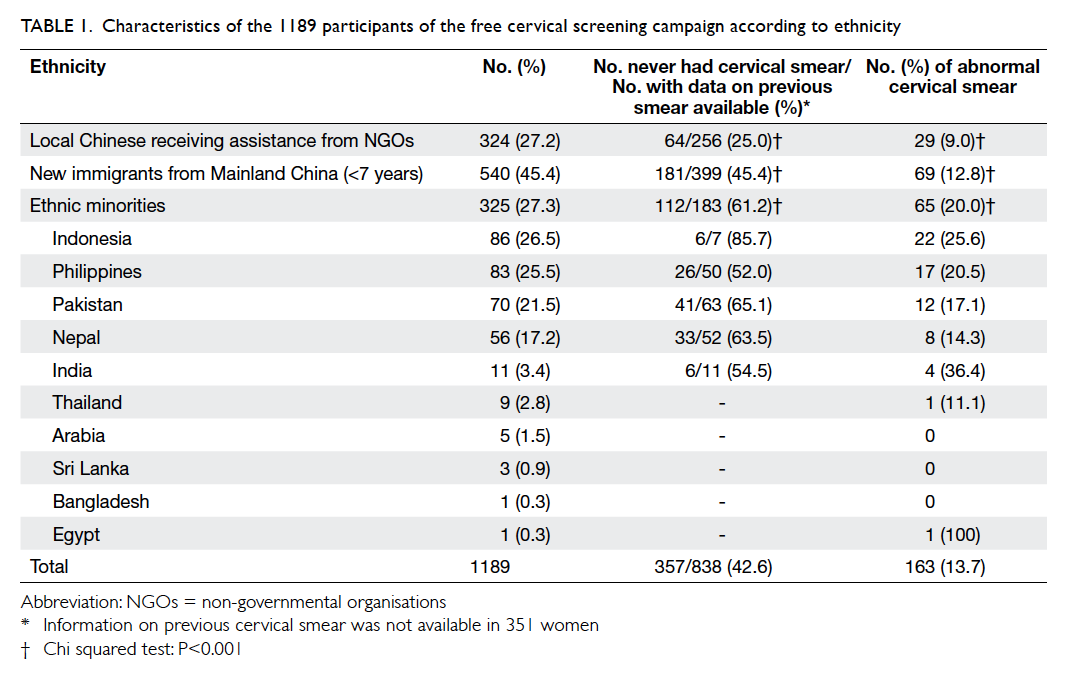

There were 163 women with cervical smear

abnormalities in the study group, including

129 (79%) atypical cells of unknown significance (ACUS), 21 (13%) low-grade squamous

intraepithelial lesion (LSIL), and 13 (8%) high-grade

squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL). Compared

with the 1141 local Chinese women in the comparison group, the

study group had a significantly higher proportion of

women who had never had a cervical smear (42.6%

vs 0%; P<0.001), and a significantly higher prevalence

of cervical smear abnormalities (13.7% vs 1.4%;

P<0.001), including ACUS (10.8% vs 0.5%; P<0.001),

LSIL (1.8% vs 0.8%; P=0.036), and HSIL (1.1% vs

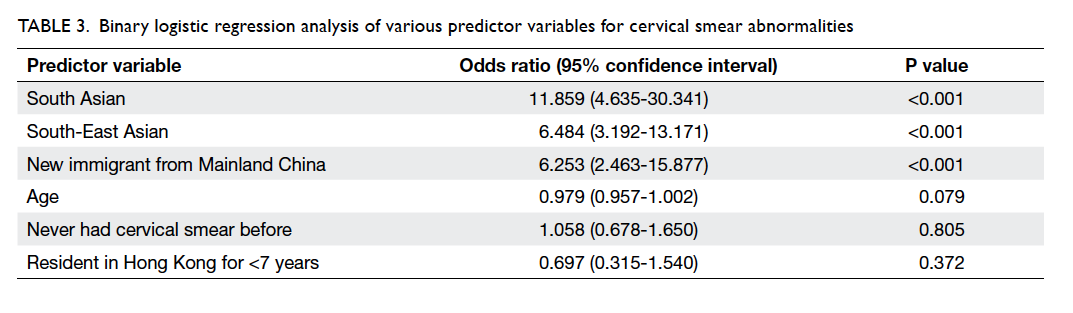

0.1%; P=0.002) [Table 2]. Binary logistic regression

analysis showed that the strongest predictors for

abnormal cervical smear were being South Asian

(odds ratio [OR]=11.859; 95% confidence interval

[CI], 4.635-30.341), South-East Asian (OR=6.484;

95% CI, 3.192-13.171), or a new immigrant from

Mainland China (OR=6.253; 95% CI, 2.463-15.877)

[Table 3].

Table 3. Binary logistic regression analysis of various predictor variables for cervical smear abnormalities

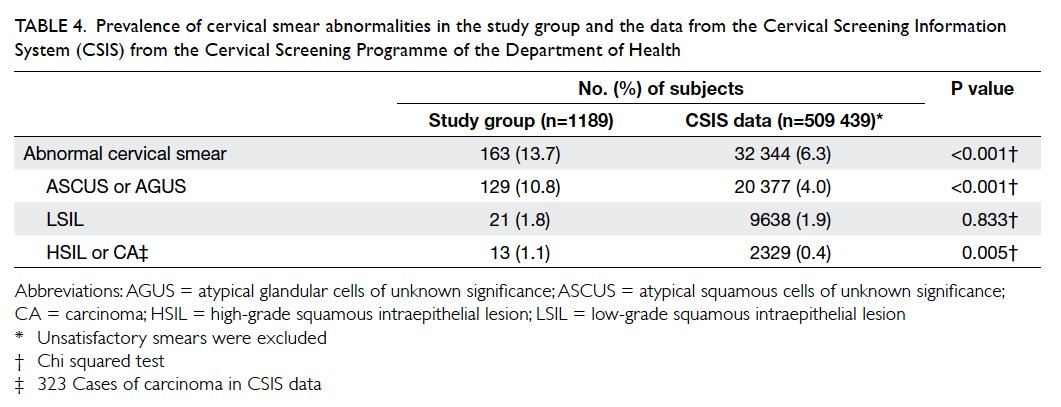

We also compared the prevalence of cervical

smear abnormalities in the study group with another

data set that consisted of 509 439 cervical cytology

tests first recorded among registered women in

the Cervical Screening Information System (CSIS)

from the Cervical Screening Programme of the

Department of Health from 2004 to 2014.10 Similar

to the previous findings, the study group once again

had a significantly higher prevalence of cervical

smear abnormalities (13.7% vs 6.3%; P<0.001),

including ACUS (10.8% vs 4.0%; P<0.001) and HSIL

(1.1% vs 0.4%; P=0.005) although the prevalence of

LSIL was not significantly different (1.8% vs 1.9%;

P=0.833) [Table 4].

Table 4. Prevalence of cervical smear abnormalities in the study group and the data from the Cervical Screening Information System (CSIS) from the Cervical Screening Programme of the Department of Health

We attempted to contact those women with

an abnormal cervical smear to ensure compliance

with subsequent gynaecological assessment and

treatment after the events and were successful in 58

(36%) instances. Among the 47 women with ACUS,

30 (64%) attended for subsequent assessment, three

underwent colposcopy and one had loop excision. Of

the six women with LSIL, five attended subsequent

assessment of whom four underwent colposcopy and

none required loop excision. All five women with

HSIL attended subsequent colposcopic assessment

and four had loop excision.

Discussion

Cervical cancer is an important health issue for

women in Hong Kong. It is the eighth most common

cancer in the local female population.11 Over the

past three decades, the ASR of cervical cancer has

declined from 25 per 100 000 in 1983 to 8.7 per

100 000 in 2013.11 The figure remains higher than

that of other high-income countries such as Finland

(ASR=4.3 per 100 000).1 After the organised cervical

screening programme was launched, the ever-screened

rate increased from 37% in 2003 to 64%

2008,12 and remained approximately 70% until 2014.5 As this programme does not proactively recruit

eligible women, 30% remain never-screened.5 Studies

show that these women tend to be immigrants or

have a lower socio-economic status with lower

family income.6 7 8 9 13 In Hong Kong, 20% of women

belonged to these groups. In 2012, there were 1.02

million people living below the poverty line in Hong

Kong; 250 000 were adult women and comprised

7.3% of our female population.14 15 In 2011, there were 171 322 mainlanders who had been resident

in Hong Kong for less than 7 years; 80 237 were

women aged 25 to 54 years, comprising 2.3% of our

female population.15 16 Immigrants from other ethnic groups constituted 10.2% of our female population

in 2011; 7% were South-East Asian domestic helpers

from Philippines, Indonesia, and Thailand, and

the remaining 3% were South Asians from India,

Pakistan, and Nepal.15 Studies show that immigrants

often develop cervical cancer at rates more akin to

their country of origin.13 Since these countries have a

high prevalence of cervical cancer with ASR ranging

from 16 to 22 per 100 000,1 it is not surprising that

our study group had a significantly higher prevalence

of cervical smear abnormalities than the comparison

group (13.7% vs 1.4%). This also explains the 6- to

11-fold higher risk of cervical smear abnormalities in

South Asian, South-East Asian, and new immigrants

from Mainland China. More importantly, almost

half (42.6%) of these women had never had a cervical

smear. This was particularly true for ethnic minority

women (61.2%) and new immigrants from Mainland

China (45.4%). This shows that there are inequalities

in our community in the access to cervical screening,

similar to most metropolitan cities worldwide.17 18 The resultant under-screening of high-risk women

and over-screening of low-risk women are clearly

demonstrated by the significant difference in

prevalence of cervical smear abnormalities between

our study group and comparison group. To ensure

that cervical screening services reach these

marginalised women, it is imperative to understand

the barriers to screening.

Cost is a common barrier for low-income

women and immigrants with economic hardship.6 7 8 13

Of the female mainlanders who had been resident in

Hong Kong for less than 7 years, 7.6% were in receipt

of social assistance.16 Foreign domestic helpers earn

only HK$4210 a month. The charge for a cervical

smear provided by the public health sector is HK$100

and may be unaffordable by some women. Even

if the screening service is free, other costs related

to attending screening, such as transportation

and taking time-off work, are deterrents.13 These

barriers can be surmounted by community

outreach that refers to the efforts made beyond

the walls of the health care facility to reach target

populations.19 The first step of outreach is to identify

the target populations and this can be facilitated

by collaboration with NGOs.13 19 Provision of a free service in mobile screening units outside working

hours is also effective.19 Studies also show that the

availability of female service providers helps reduce

embarrassment about cervical cancer screening, and

thus reluctance to attend, among Chinese and other

ethnic groups.6 7 8 13 19 Utilising these strategies, we

organised free screening events during weekends by

women doctors, and we have successfully attracted

almost 1200 marginalised women to participate.

Another important barrier to screening is

ignorance about cervical cancer prevention and

lack of awareness of screening service access,6 7 8 9 13 19 consequent to low health literacy.13 20 Health literacy

refers to how easy it is for an individual to obtain,

process, and understand health information and

services to make appropriate health decisions.13

Low health literacy means that a person is unable to

understand the health information available, access

health services effectively, and make informed

health decisions.20 In other words, health literacy

is dependent not only on the education level and

literacy of the individual, but also on how well health

information is delivered and how accessible the

health service is to the individual. Efforts to improve

health literacy will help reduce health inequalities.20

For women with a low education level or low literacy,

rewriting pamphlets in simple language or employing

non-written forms of communication such as radio

and television programmes are recommended.13 19

In Hong Kong, television programmes designed

to promote cervical cancer screening are available,

but they are broadcast in the local Cantonese

dialect.21 As 68.3% of ethnic minority adults do

not understand Chinese language and 36% of the

new female immigrants from Mainland China do

not speak Cantonese,22 23 they will not benefit from

these programmes. It is worthwhile to translate

these educational materials into different languages.

In our recent free cervical cancer screening events,

health talks on cervical cancer prevention were given

with simultaneous translation into languages spoken

by the participants, aiming to empower them to

become peer health educators in their families and

circle of friends, so that the health literacy in their

community could be improved.

It is now known that cervical cancer is caused

by human papillomavirus (HPV). Vaccination

against HPV for 9- to 13-year-old girls combined

with regular screening for precancerous lesions in

women aged over 30 years followed by adequate

treatment are now the key preventive approaches

against cervical cancer.24 We have launched a free

HPV vaccination programme for 9- to 18-year-old

girls in this marginalised population. Since 2013,

176 girls from low-income families and 24 girls from

ethnic minority groups have been vaccinated. It is

hoped that our free cervical smear programme and

free HPV vaccination programme will help reduce

the incidence of cervical cancer in these marginalised

women.

Limitations

Our study was a retrospective analysis of data

obtained from our free cervical cancer screening

campaign. Limited by the nature of the campaign,

important information such as occupation,

education level, household income, and reasons for

not attending screening was not obtained. Some

data on the history of cervical smear were

missed due to a language barrier. Moreover, self-reported

smear history may not be reliable in this

group of women with low health literacy.

The comparison group may not be ideal as

it may represent an ultra-low-risk population,

as reflected by the low prevalence of cervical

smear abnormalities in these women who had

regular cervical smears. Nonetheless, this is the

only accessible data set from which to obtain the

necessary raw data for analysis. Moreover, limited by

the scarcity of data available on the smear reports

from the Well Women Clinic, the only means to

avoid including women with a similar background to

those in the study group was by excluding reports

bearing foreign names and those with the first

alphabet of the identity card number being R, M, or

W. When we compared the prevalence of cervical

smear abnormalities in the study group with the

CSIS data,10 which may be more representative of the

general population, the findings remained similar

and the prevalence of cervical smear abnormalities

remained 2-fold higher (Table 4).

It would be more informative to have data

about HPV DNA testing on all abnormal smears,

but unfortunately the test was not covered by the

charitable fund. The picture would also be more

complete if the colposcopic or histological diagnosis

of those women with abnormal cervical smears was

available. Such information could not be obtained

without the individual’s consent. We did attempt

to contact these women to ensure compliance with

subsequent gynaecological assessment and treatment

after the event, but were successful in only 36% of

cases as they came from a very mobile population.

It is encouraging that most contactable women with

LSIL or HSIL did attend subsequent assessment,

and almost all with HSIL received treatment. It is

hoped that by identifying and treating precancerous

lesions, our campaign may help reduce the incidence

of cervical cancer in these marginalised women.

Conclusions

The prevalence of cervical smear abnormality in

marginalised women is at least double that of the

general population and almost half had never had

a cervical smear. South Asian, South-East Asian,

and new immigrants from Mainland China had

a 6- to 11-fold increased risk of cervical smear

abnormalities compared with local Chinese

population. The Government should play a proactive

role in developing a more comprehensive cervical

cancer screening programme in Hong Kong and

ensuring adequate coverage for marginalised women

by developing community outreach programmes

through collaboration with community NGOs.

Acknowledgements

We thank the following organisations for

collaboration in the ‘Ripple Action’ and ‘WE Stand’

projects (in alphabetical order): Association of

Women Accountants (Hong Kong) Ltd, GoodNews

Communication International, Hepatitis Free

Generation, Hong Kong Ap Lei Chau Women’s

Association, Hong Kong Employment Development

Service, Hong Kong Federation of Women, Hong

Kong Federation of Women Lawyers, Hong Kong

Island Women’s Association, Hong Kong Nurses

General Union, Hong Kong Outlying Islands

Women’s Association, Hong Kong Playground

Association, Hong Kong Sheng Kung Hui Lady

MacLehose Centre, Hong Kong Sheng Kung Hui

Welfare Council Limited, Hong Kong Women

Doctors Association, International Social

Service Hong Kong Branch, Kowloon Women’s

Organisations Federation, Narcotics Division of

Security Bureau, Po Tat Women’s Association,

RainLily Association Concerning Sexual Violence

Against Women, Social Welfare Department, The

Neighbourhood Advice-Action Council, Village

Volunteers of Hong Kong Sanatorium and Hospital,

Yang Memorial Methodist Social Service Family

Education and Support Centre, and Yuen Long Town

Hall Support Service Centre for Ethnic Minorities.

We thank Dr Ellen Li Charitable Foundation for

funding all the cervical smears in the ‘Ripple Action’

and ‘WE Stand’ projects. We thank Zonta Club of

Kowloon for sponsoring all the HPV vaccines. We

thank Dr KL Mak for retrieving cervical smear

data for the comparison group; Prof DS Sahota for

statistical support; Prof TKH Chung, Prof SSC Ho,

and Prof TC Li for editorial assistance; and Prof HYS

Ngan, the advisor of the ‘Ripple Action’ and ‘WE

Stand’ free cervical screening projects.

Declaration

All the cervical smears taken in the “Ripple Action”

and “WE Stand” projects were funded by Dr Ellen Li

Charitable Foundation. All the HPV vaccines were

sponsored by Zonta Club of Kowloon. All authors

have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, et al. GLOBOCAN

2012 v1.0. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide:

IARC CancerBase No. 11. Lyon, France: International

Agency for Research on Cancer; 2013. Available from:

http://globocan.iarc.fr. Accessed 17 Feb 2016.

2. Denny L, Quinn M, Sankaranarayanan R. Chapter 8:

Screening for cervical cancer in developing countries.

Vaccine 2006;24 Suppl 3:S3/71-7.

3. Gakidou E, Nordhagen S, Obermeyer Z. Coverage of

cervical cancer screening in 57 countries: low average

levels and large inequalities. PLoS Med 2008;5:e132. Crossref

4. Surveillance and Epidemiology Branch, Centre for Health

Protection, Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR

Government. Topical health report No. 4: Prevention and

screening of cervical cancer. Available from: http://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/grp-THR-report4-en-20041209.pdf.

Accessed 17 Feb 2016.

5. Cervical screening programme: statistics and reports.

Available from: http://www.cervicalscreening.gov.hk/english/sr/sr_statistics_ccsc.html. Accessed 17 Feb 2016.

6. Wang LD, Lam WW, Fielding R. Cervical cancer

prevention practices through screening and vaccination: A

cross-sectional study among Hong Kong Chinese women.

Gynecol Oncol 2015;138:311-6. Crossref

7. Wang LD, Lam WW, Wu J, Fielding R. Hong Kong Chinese

women’s lay beliefs about cervical cancer causation and

prevention. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2014;15:7679-86. Crossref

8. Holroyd E, Twinn S, Adab P. Socio-cultural influences on

Chinese women’s attendance for cervical screening. J Adv

Nurs 2004;46:42-52. Crossref

9. Adab P, McGhee SM, Yanova J, Wong LC, Wong CM,

Hedley AJ. The pattern of cervical cancer screening in

Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J 2006;12(Suppl 2):S15-8.

10. Cervical Screening Programme annual statistics report

2014. Available from: http://www.cervicalscreening.gov.hk/english/sr/files/2014_Eng.pdf. Accessed 17 Feb 2016.

11. Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR Government.

Cervical cancer. Available from: http://www.chp.gov.hk/en/content/9/25/56.html. Accessed 14 Sep 2016.

12. Wu J. Cervical cancer prevention through cytologic and

human papillomavirus DNA screening in Hong Kong

Chinese women. Hong Kong Med J 2011;17(3 Suppl 3):S20-4.

13. Schleicher E. Immigrant women and cervical cancer

prevention in the United States. Available from: http://www.jhsph.edu/research/centers-and-institutes/womens-and-childrens-health-policy-center/publications/ImmigrantWomenCerCancerPrevUS.pdf. Accessed 17 Feb

2016.

14. Lam C. Hong Kong’s first official poverty line—purpose

and value. Available from: http://www.povertyrelief.gov.hk/eng/pdf/20130930_article.pdf. Accessed 17 Feb 2016.

15. 2011 Hong Kong Population Census. Population by

ethnicity, sex and economic activity status, 2011 (C110).

Available from: http://www.census2011.gov.hk/en/maintable/C110.html. Accessed 17 Feb 2016.

16. 2011 Hong Kong Population Census. Thematic report:

Persons from the Mainland having resided in Hong Kong

for less than 7 Years. Available from: http://www.statistics.gov.hk/pub/B11200612012XXXXB0100.pdf. Accessed 17

Feb 2016.

17. Grillo F, Vallée J, Chauvin P. Inequalities in cervical cancer

screening for women with or without a regular consulting

in primary care for gynaecological health, in Paris, France.

Prev Med 2012;54:259-65. Crossref

18. Moser K, Patnick J, Beral V. Inequalities in reported use of

breast and cervical screening in Great Britain: analysis of

cross sectional survey data. BMJ 2009;338:b2025. Crossref

19. Comprehensive cervical cancer control: a guide to essential

practice. 2nd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization;

2014.

20. Kanj M, Mitic W. Promoting health and development:

closing the implementation gap. Available from: http://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/7gchp/Track1_Inner.pdf. Accessed 17 Feb 2016.

21. Twinn SF, Holroyd E, Fabrizio C, Moore A, Dickinson JA.

Increasing knowledge about and uptake of cervical cancer

screening in Hong Kong Chinese women over 40 years.

Hong Kong Med J 2007;13(Suppl 2):S16-20.

22. 2011 Hong Kong Population Census. Thematic report:

Ethnic minorities. Available from: http://www.statistics.gov.hk/pub/B11200622012XXXXB0100.pdf. Accessed 17

Feb 2016.

23. Central Policy Unit, Hong Kong SAR Government. A

study of new arrivals from Mainland China; 25 Jan 2013.

Available from: http://www.cpu.gov.hk/doc/en/research_reports/A_study_on_new_arrivals_from_Mainland_China.pdf. Accessed 17 Feb 2016.

24. Comprehensive cervical cancer prevention and control—a

healthier future for girls and women: WHO guidance note.

World Health Organization; 2013.