Hong Kong Med J 2017 Feb;23(1):19–27 | Epub 24 Oct 2016

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj154754

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Ductal carcinoma in situ of breast: detection and

treatment pattern in Hong Kong

TK Yau, FHKCR, FHKAM (Radiology);

Amy Chan, BSc, MPhil;

Polly SY Cheung, FRACS, FHKAM (Surgery)

Hong Kong Breast Cancer Foundation, 22/F, Jupiter Tower, No. 9, Jupiter

Street North Point, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr TK Yau (research@hkbcf.org)

Abstract

Introduction: The treatment of ductal carcinoma

in situ has been widely reported in the western and

other Asian countries, but the relevant data in Hong

Kong are relatively limited. This study aimed to

evaluate the latest detection and treatment pattern

for ductal carcinoma in situ in Hong Kong so as to

guide planning of future service provision.

Methods: This was a retrospective case series study.

A total of 573 patients who registered with the Hong

Kong Breast Cancer Registry, and were diagnosed

and treated in Hong Kong from January 2001 to

December 2011 were reviewed.

Results: Compared with invasive breast cancer

patients, patients with ductal carcinoma in situ

were younger (median, 48.6 vs 50.3 years; P<0.001),

had a higher education level (P<0.001), had a

higher total monthly family income (P<0.001), and

more common breast-screening habits (P<0.001).

Significantly more patients with ductal carcinoma

in situ underwent breast-conserving surgery than

their invasive cancer counterparts (55.8% vs 36.7%;

P<0.001). The percentage of screen-detected ductal

carcinoma in situ was relatively lower than that

reported in other studies, but was still much higher

than that in invasive breast cancer patients (29.0% vs

4.7%; P<0.001). Screen-detected patients with ductal

carcinoma in situ tended to choose a private hospital

instead of a public hospital for treatment (P=0.05)

and to undergo breast-conserving surgery (P=0.02).

With a median follow-up of 3 years, the crude

local recurrence rate after mastectomy and breast-conserving

surgery was 0.4% and 3.3%, respectively;

44% of recurrent tumours had developed invasive

components. No regional recurrence, distant

recurrence, or cancer-related deaths were recorded.

Conclusions: In the absence of a population-based

breast screening programme in Hong Kong, ductal

carcinoma in situ is more frequently found in the

higher social classes and managed in the private

sector. The clinical outcome of ductal carcinoma in

situ is excellent and more than half of the patients can

be successfully managed with breast-conserving

surgery.

New knowledge added by this study

- This is the largest comprehensive study to evaluate the pattern of care for patients with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) in Hong Kong.

- Further studies are needed to evaluate the long-term clinical outcome of DCIS in Hong Kong.

Introduction

Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) of the breast

is a non-invasive, pre-cancerous lesion that

was uncommon prior to the widespread use of

mammography (MMG) screening; it is traditionally

treated by mastectomy (MTX) with cure rates

approaching 100%.1 The high incidence rate and

mortality rate of breast cancer in women2 has

led to the setting up of population-based breast

cancer screening programmes by government in 34

countries.3 4 5 6 One of the results of the popularity of

breast screening is the rise in the detected incidence

of DCIS.7 Some western studies revealed that DCIS

constituted approximately 10% to 40% of lesions

detected by MMG screening.8 In Asia, following

the pilot Singapore Breast Screening Project, the

diagnosis of DCIS also increased markedly.9 Screen-detected

DCIS showed a better clinical profile such

as smaller size and higher chance of being treated by

breast-conserving surgery (BCS).9 Early detection of

breast cancer at this stage offers the best opportunity

for curative treatment.10

The treatment of DCIS has been widely

studied and reported in the western and other

Asian countries.11 12 13 14 15 16 Although there have been no

prospective randomised trials to compare MTX

with BCS for DCIS, BCS has been widely accepted

as an alternative treatment,17 especially for small

mammographically detected lesions. In Hong

Kong, however, data on DCIS are relatively limited.

The Hong Kong Cancer Registry has only started

to release basic data of annual incidence and age

distribution of DCIS since 2009. In 2012, 3508 women

in Hong Kong were diagnosed with invasive breast

cancer and 477 women were diagnosed with DCIS18

that constituted only 12.0% of the total number of

breast cancer patients diagnosed. This incidence of

DCIS was relatively low compared with the 20.7%

in the United States.14 Since our presentation and

treatment pattern of DCIS are likely different to that

in other countries, it is necessary to examine the

particular pattern of care of DCIS in Hong Kong to

better understand this disease.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the

latest detection and treatment pattern for DCIS in

Hong Kong so as to guide planning of future service

provision.

Methods

The Hong Kong Breast Cancer Registry (HKBCR)

was first established in 2007 by the Hong Kong

Breast Cancer Foundation as a data collection and

monitoring system for breast cancer in Hong Kong.

The HKBCR aims to collect and analyse data from

all Hong Kong breast cancer patients to obtain

comprehensive information about demographics,

risk exposures, treatments, clinical outcomes,

and psychosocial impact on patients. It is the first

population-wide, cancer-specific registry for breast

cancer patients in Hong Kong and has been a member

of the International Association of Cancer Registries

since 2011, providing international standard data

management and accuracy.

Between 2008 and 2011, a total of 5393 patients

with a history of in-situ or invasive breast cancers

were registered with the HKBCR on a voluntary basis.

Of these patients, 2539 (47.1%) and 2854 (52.9%)

were recruited from private clinics or hospitals and

public hospitals, respectively. Demographics and

risk exposure data were collected from these patients

by questionnaire; clinical characteristics, detection

methods, diagnostic methods, disease stage,

histopathological profile, treatment modalities, and

clinical outcome data were extracted from their

medical records.19 Data analysis was carried out in

December 2014.

Inclusion criteria for this study were as follows:

female patient being diagnosed and treated in

Hong Kong from January 2001 to December 2011;

pure DCIS with no invasive element in ipsilateral

or contralateral breast at the time of diagnosis;

definitive surgery performed; complete pathology

details available; if axillary node sampling/dissection

was performed, the nodal status must be negative;

and no prior neoadjuvant treatment administered.

Overall, 573 patients, including 16 synchronous

patients with bilateral DCIS, from the HKBCR

fulfilled the above criteria for further study.

For comparison purposes, the records of

female patients with invasive breast cancer diagnosed

and treated in Hong Kong during the same period

were also extracted from HKBCR. Altogether,

1611 invasive breast carcinoma patients with 20

synchronous bilateral patients were retrieved for

data analysis.

In this study, local recurrence was defined as

the reappearance of cancer, invasive or non-invasive,

in the treated breast or chest wall before or at the time

of regional or distant metastases. All events were

measured from the date of the definitive surgery.

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the

patterns of demographic and pathological features.

Statistical significance was tested using Chi squared

tests for categorical variables. The Kaplan-Meier

method was applied to analyse the local recurrence

estimation. All statistical tests were two-sided and

performed at the 0.05 level of significance (P value).

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

(Windows version 19.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago [IL], US)

was used for all statistical analyses.

The project was approved by respective Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee of the following hospitals: Hong Kong Sanatorium & Hospital, Hong Kong Baptist Hospital, Hong Kong Adventist Hospital, Princess Margaret Hospital, United Christian Hospital, Prince of Wales Hospital, Queen Mary Hospital, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Pok Oi Hospital, North District Hospital, Tuen Mun Hospital, and Yan Chai Hospital. All participants provided written informed consent.

Results

Of the 573 patients with DCIS of breast, the majority

(74.9%) were diagnosed and treated between 2006

and 2011. A similar distribution was found in the

1611 patients with invasive breast cancer.

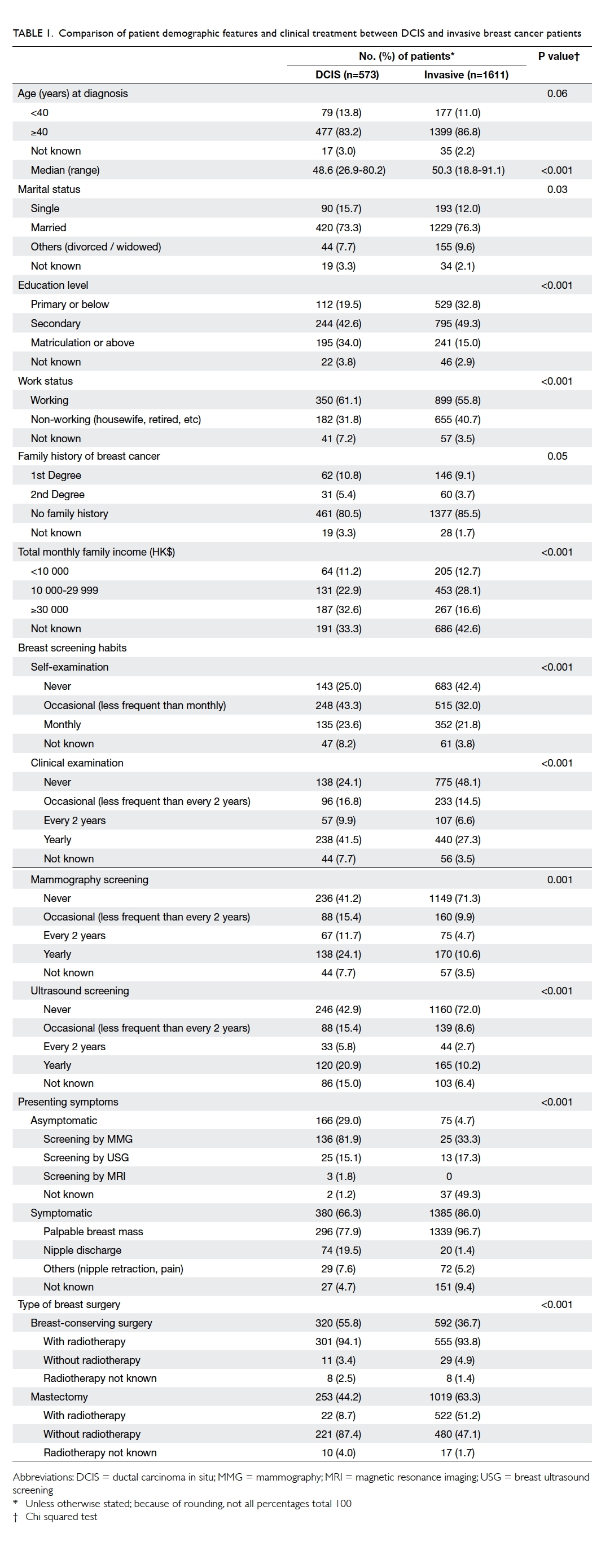

Table 1 compares the demographic characteristics of DCIS and invasive breast cancer

patients. The results indicate that DCIS patients were

significantly younger (median, 48.6 vs 50.3 years;

P<0.001), had a higher education level (matriculation

or above, 34.0% vs 15.0%; P<0.001), were more likely

to be working (61.1% vs 55.8%; P<0.001), and had a

higher total monthly family income of HK$30 000

or above (32.6% vs 16.6%; P<0.001). More DCIS

patients had regular breast screening habits in the

form of self-examination (monthly: 23.6% vs 21.8%;

P<0.001), clinical breast examination (yearly: 41.5%

vs 27.3%; P<0.001), MMG screening (yearly: 24.1%

vs 10.6%; P<0.001), and breast ultrasound screening

(yearly: 20.9% vs 10.2%; P<0.001). Patients with DCIS

had a much higher chance of being asymptomatic at

diagnosis (ie screen-detected) than their invasive

breast cancer counterparts (29.0% vs 4.7%; P<0.001).

Significantly more DCIS patients underwent BCS

than their invasive cancer counterparts (55.8% vs

36.7%; P<0.001). Among those treated by BCS, DCIS

patients had a similar chance of receiving adjuvant

radiotherapy as the invasive cancer patients (94.1%

vs 93.8%). As expected, only very few (8.7%) DCIS

patients required adjuvant radiotherapy after MTX.

Although DCIS patients do not require systemic

adjuvant therapy, some may be prescribed hormone

therapy as chemoprevention. In our study, only a

small percentage of DCIS patients received hormone

therapy and the pattern was similar after BCS

or MTX (19.4% after BCS and 17.0% after MTX;

P<0.001).

Table 1. Comparison of patient demographic features and clinical treatment between DCIS and invasive breast cancer patients

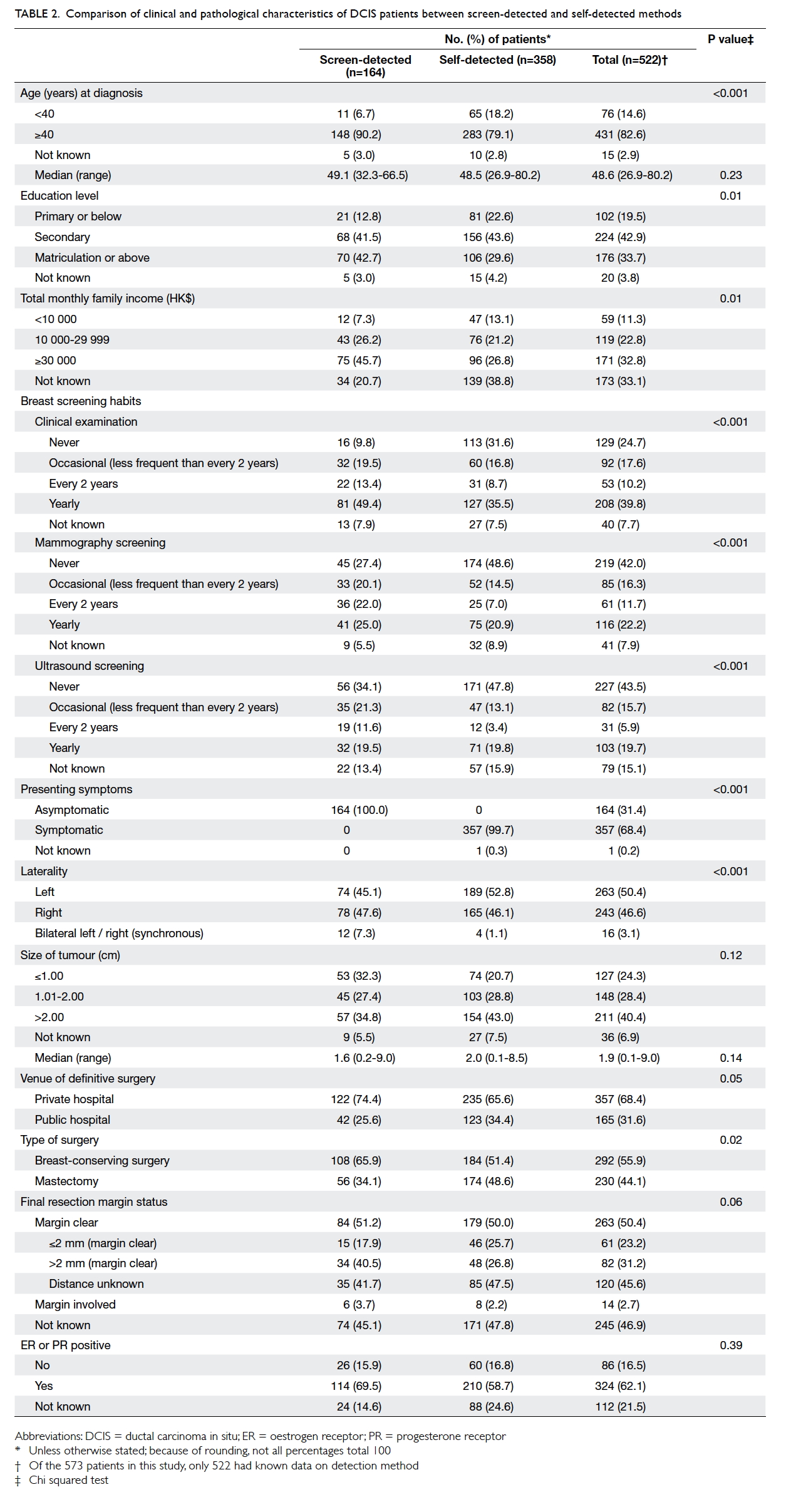

Table 2 shows the patient demographics, and clinical and pathological characteristics of

screen-detected (asymptomatic) and self-detected

(symptomatic) DCIS in Hong Kong. There was no

significant difference in the median age between

these subgroups (49.1 vs 48.5 years; P=0.23). The

screen-detected subgroup had a significantly higher

education level (matriculation or above, 42.7% vs

29.6%; P=0.01), higher total monthly family income

of HK$30 000 or above (45.7% vs 26.8%; P=0.01), and

underwent more regular clinical breast examination

(yearly: 49.4% vs 35.5%; P<0.001), MMG (every 2

years: 22.0% vs 7.0%; P<0.001), and breast ultrasound

screening (every 2 years: 11.6% vs 3.4%; P<0.001).

Table 2. Comparison of clinical and pathological characteristics of DCIS patients between screen-detected and self-detected methods

Among the DCIS patients, 28.6% (164/573)

were screen-detected: since MMG screening is not

usually recommended in younger women, only 14.5%

(11/76) of DCIS in patients aged below 40 years were

screen-detected compared with 34.3% (148/431) in

patients aged above 40 years. Irrespective of the type

of presentation, two thirds or more of DCIS patients

chose to have surgery at a private hospital and the

screen-detected subgroup had an even higher

tendency to do so (74.4% vs 65.6%; P=0.05). Although

there was a trend of finding smaller lesions in the

screen-detected subgroup, there was no significant

difference between the two subgroups in tumour

size (median: 1.6 cm vs 2.0 cm; P=0.14). Despite this

finding, screen-detected DCIS patients had a higher

chance of being treated by BCS than symptomatic

patients (65.9% vs 51.4%; P=0.02) [Table 2].

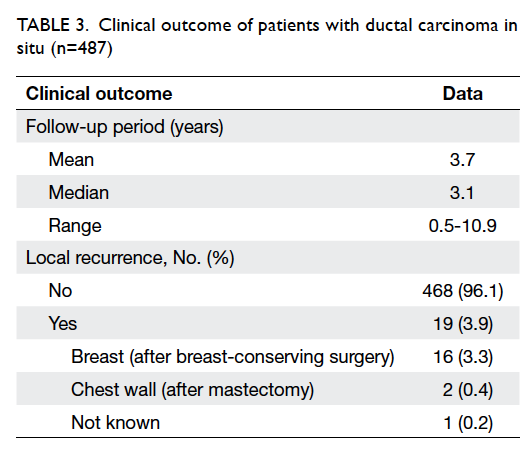

Among 573 patients with DCIS, clinical

outcome data were available for 487 patients only.

With a median follow-up of 3.1 (range, 0.5-10.9)

years, the early clinical outcome was very good and

compatible with other series. The overall crude local

recurrence rate in DCIS patients was 3.9% (19 in 487

patients) and, as expected, there was a significant

difference between MTX and BCS patients (0.4%

vs 3.3%) [Table 3]. Of the 18 patients with known pathology at recurrence, eight (44.4%) had developed

invasive components. Of the 16 BCS patients, 11

(68.8%) underwent salvage MTX at recurrence.

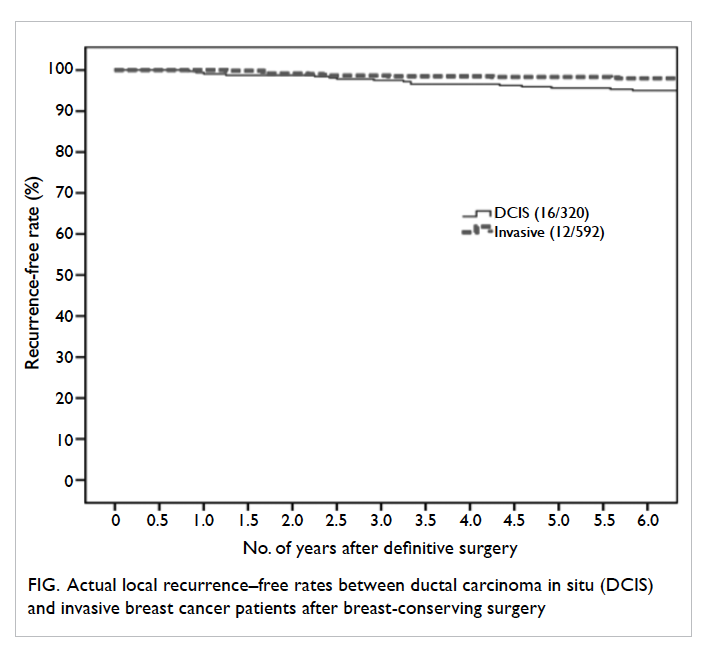

Overall, by 6 years, the projected local recurrence

rates after BCS were similar for DCIS patients and

invasive breast cancer patients (log rank, P=0.21; Fig). No regional recurrence, distant recurrence,

or cancer-related death were observed in the DCIS

patients.

Figure. Actual local recurrence–free rates between ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) and invasive breast cancer patients after breast-conserving surgery

Discussion

Ductal carcinoma in situ was relatively uncommon

in western countries until the widespread use of

mass breast screening. There is strong evidence

that the recent rise in DCIS incidence is related to

the popularity of breast screening. Since there is no

government-funded breast screening programme in

Hong Kong, our study showed that only 29.0% of the

DCIS in Hong Kong was first detected by screening,

significantly lower than the 80% screen-detected rate

in DCIS of other studies.20 21 22 23 24 Our data showed that

these DCIS patients in general had a higher monthly

family income and higher level of education than

their invasive cancer counterparts and this may

contribute to their higher acceptance of self-funded

breast screening, higher breast cancer awareness,

and hence better chance of detecting breast cancer at

an early stage. Not surprisingly, the use of BCS was

also significantly more popular in the DCIS patients

compared with their invasive cancer counterparts

(55.8% vs 36.7%; P<0.001). Our results were also

consistent with a previous local study that reported

the performance of opportunistic breast screening

in local well women clinics and showed that breast

screening could achieve a higher cancer detection

rate and detect the cancer at an early stage.25

In contrast, the profile of screen-detected

and self-detected (ie symptomatic) DCIS patients

showed more similarities than differences. The overall

tumour size was not significantly different between

these subgroups, although lesions of >2 cm were less

common in the screen-detected patients (34.8%

vs 43.0%; P=0.12). Since there is no population-based

breast screening programme in Hong Kong,

these opportunistic breast screenings performed in

various laboratories may have inherent limitations.

Overseas studies have shown a considerably higher

sensitivity in organised population-based screening

than in opportunistic screening,24 although a large-scale

local self-referred breast screening centre

reported comparable performance.25

Our study showed a high acceptance of BCS for

management of DCIS in Hong Kong and nearly all

(94.1%) BCS patients also underwent postoperative

radiotherapy. Although prior randomised studies

have demonstrated the benefit of postoperative

radiotherapy in reducing both invasive and non-invasive

recurrence of DCIS after BCS, much

effort has been put into identifying a low-risk

subgroup in whom postoperative radiotherapy can

be safely omitted.26 The Van Nuys prognostic index

(VNPI)—a retrospectively derived risk classification

that combines tumour size, margin width, and

pathological classification—was developed to select

this low-risk group.27 Nonetheless, perhaps due

to contradictory findings from other studies that

reported a much higher local failure rate in the

VNPI low-risk subgroup,28 it is apparent that most

clinicians in Hong Kong had reservations when

applying the VNPI to their DCIS patients.

Although tamoxifen after local excision for

DCIS has been shown to reduce the risk of recurrent

DCIS in the ipsilateral breast (hazard ratio=0.75; 95%

confidence interval [CI], 0.61-0.92) and contralateral

breast (relative risk=0.50; 95% CI, 0.28-0.87)29 and

over 60% of our patients had positive hormonal

receptors, less than 20% DCIS patients in Hong Kong

actually received tamoxifen as chemoprevention.30

It is likely related to the concern about side-effects

(particularly the small risk of endometrial cancer)

and the lack of overall survival benefit as shown by

the Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis.29

The lack of survival benefit is consistent with the

clinical experience that most new lesions detected

during follow-up surveillance are highly treatable.

As expected, the local recurrence rate after

MTX was very low (0.4%) in these DCIS patients;

it should be noted that 8.7% had received adjuvant

radiotherapy, probably because of close resection

margins. For DCIS patients treated by BCS, the

crude local recurrence rate in our study was 3.3%

(16 in 320 patients) and was quite similar to the

long-term experience in another regional hospital

(Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital) in Hong

Kong. In their analysis of 155 DCIS patients treated

by BCS and radiotherapy, after a 10-year median

follow-up, the crude local recurrence rate was 5.8%

(unpublished data of Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital). Our study did

not capture the data on the mode of detection of

local recurrences but another local study reported

that only 43% of in-breast recurrences could be

first detected by surveillance breast imaging; the

rest presented with either nipple discharge or a

palpable mass.30 Hence, patients should be advised

not to become overly dependent on breast imaging

to detect early recurrences. Although there were no

cancer-related deaths in these DCIS patients, 44%

of local recurrences in this study contained invasive

components that may still necessitate systemic

treatment in addition to further salvage surgery.

This study provides the first comprehensive

analysis of the pattern of care of DCIS in

Hong Kong. The strength of this analysis is the

comprehensiveness compared with other cancer

registries in data collection on epidemiological,

pathological, and treatment characteristics for

breast cancer. Nonetheless, data from HKBCR

might not be representative of all breast cancers in

Hong Kong since a higher proportion of patients

were recruited from private hospitals or clinics

than public hospitals in Hong Kong. Since the data

collection was done on a voluntary basis and only

started in 2008, some clinical outcome data may be

missing (approximately 10% of DCIS patients) and

the follow-up duration remains relatively short,

and may not represent the whole local population.

There was also a high proportion of missing data

for family income in the two internal comparisons.

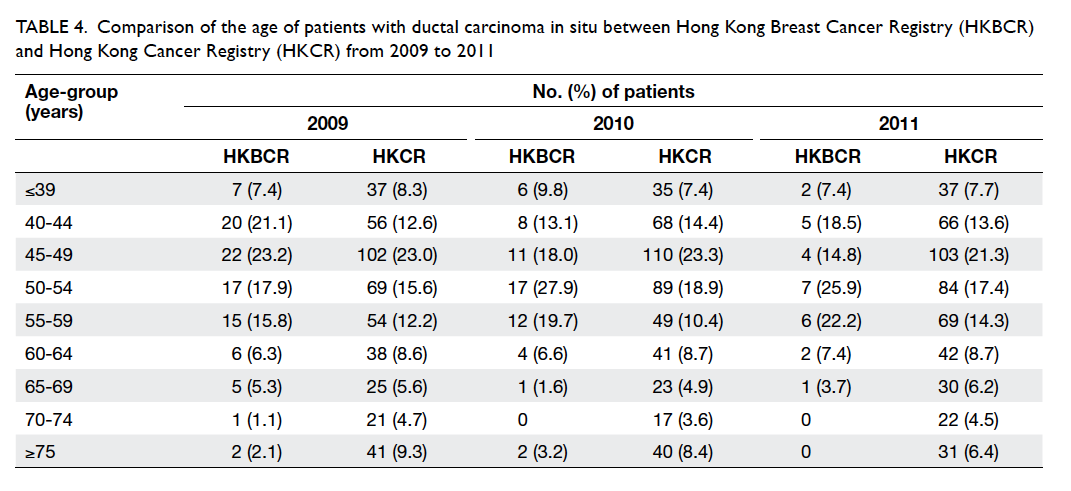

Although the distribution of age at diagnosis in our

study did not deviate too far from that reported in

the Hong Kong Cancer Registry (a population-based

registry; Table 4), older age-groups, especially those aged 70 years and above, were under-represented

in the present study. Furthermore, we did not have

information on education, occupation, and family

income to enable comparison of socio-economic

backgrounds.

Table 4. Comparison of the age of patients with ductal carcinoma in situ between Hong Kong Breast Cancer Registry (HKBCR) and Hong Kong Cancer Registry (HKCR) from 2009 to 2011

Conclusions

Ductal carcinoma in situ in Hong Kong appears to be

a more prevalent disease in the higher social classes

with a tendency to be managed in the private sector.

More than half of DCIS patients can be successfully

treated with BCS and the early outcome is excellent

and comparable with overseas studies.9 16 Further

studies are needed to examine the long-term clinical

outcome of DCIS in Hong Kong.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all of the patients/survivors,

doctors, and research staff who have participated

in HKBCR to facilitate data collection at clinics and

hospitals throughout the territory. The authors also

acknowledge the following steering committee members: Prof

Emily Chan, Dr John Chan, Dr Keeng-Wai Chan,

Dr Miranda Chan, Dr Sharon Chan, Dr Foon-Yiu

Cheung, Dr Peter Choi, Dr Josette Chor, Ms Yvonne

Chua, Ms Doris Kwan, Dr Wing-Hong Kwan, Dr

Stephen Law, Dr Simon Leung, Dr Lawrence Li, Dr

Janice Tsang, Dr Gary Tse, Mrs Cecilia Tseung, Dr

Tung Yuk, Ms Lorna Wong, Dr Ting-Ting Wong,

Dr CC Yau, Prof Winnie Yeo, and Prof Benny Zee

for providing guidance for the development of the

HKBCR.

Declaration

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Fortunato L, Poccia I, de Paula U, Santini E. Ductal

carcinoma in situ: what can we learn from clinical trials?

Int J Surg Oncol 2012;2012:296829.

2. International Agency for Research on Cancer. Globocan

2012: All cancers (excluding non-melanoma skin cancer)—estimated incidence, mortality and prevalence worldwide in 2012. Available from: http://globocan.iarc.fr/Pages/fact_sheets_cancer.aspx. Accessed 2 Apr 2015.

3. Kwong A, Cheung PS, Wong AY, et al. The acceptance and

feasibility of breast cancer screening in the East. Breast

2008;17:42-50. Crossref

4. Biesheuvel C, Weigel S, Heindel W. Mammography

screening: evidence, history and current practice in

Germany and other European countries. Breast Care

(Basel) 2001;6:104-9. Crossref

5. Cheung PS. Global and local status of breast cancer

and screening. Paper presented at Hong Kong Breast Cancer

Foundation Seminar; 2013 Apr 14; Hong Kong.

6. Hellquist BN, Duffy SW, Abdsaleh S, et al. Effectiveness of

population-based service screening with mammography

for women ages 40 to 49 years: evaluation of the Swedish

Mammography Screening in Young Women (SCRY)

cohort. Cancer 2011;117:714-22. Crossref

7. Leonard GD, Swain SM. Ductal carcinoma in situ,

complexities and challenges. J Natl Cancer Inst

2004;96:906-20. Crossref

8. Delaney G, Ung O, Bilous M, Cahill S, Greenberg M,

Boyages J. Ductal carcinoma in situ. Part I: definition and

diagnosis. Aust N Z J Surg 1997;67:81-93. Crossref

9. Chuwa EW, Yeo AW, Koong HN, et al. Early detection of

breast cancer through population-based mammographic

screening in Asian women: a comparison study between

screen-detected and symptomatic breast cancers. Breast J

2009;15:133-9. Crossref

10. Morrow M, Strom EA, Bassett LW, et al. Standard for

the management of ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast

(DCIS). CA Cancer J Clin 2002;52:256-76. Crossref

11. Irvine T, Fentiman IS. Biology and treatment of ductal

carcinoma in situ. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 2007;7:135-45. Crossref

12. Siziopikou KP. Ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast:

current concepts and future directions. Arch Pathol Lab

Med 2013;137:462-6. Crossref

13. Jiveliouk I, Corn B, Inbar M, Merimsky O. Ductal

carcinoma in situ of the breast in Israeli women treated by

breast-conserving surgery followed by radiation therapy.

Oncology 2009;76:30-5. Crossref

14. Virnig BA, Torchia MT, Jarosek SL, Durham S, Tuttle

TM. Data Points #14: Use of endocrine therapy following diagnosis of

ductal carcinoma in situ or early invasive breast cancer. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare

Research and Quality; 2011-2012.

15. Tan KB, Lee HY, Putti TC. Ductal carcinoma in situ of the

breast in Singapore: recent trends and clinical implications.

ANZ J Surg 2002;72:793-7. Crossref

16. Chuwa EW, Tan VH, Tan PH, Yong WS, Ho GH, Wong

CY. Treatment for ductal carcinoma in situ in an Asian

population: outcome and prognostic factors. ANZ J Surg

2008;78:42-8. Crossref

17. Mouw KW, Harris JR. Irradiation in early-stage breast

cancer: conventional whole-breast, accelerated partial-breast,

and accelerated whole-breast strategies compared.

Oncology (Williston Park) 2012;26:820-30.

18. Hong Kong Cancer Registry. Leading cancer sites in Hong

Kong in 2012. Available from: http://www3.ha.org.hk/cancereg/rank_2012.pdf. Accessed 15 Jan 2015.

19. Cheung P, Hung WK, Cheung C, et al. Early data from the

first population-wide breast cancer-specific registry in

Hong Kong. World J Surg 2012;36:723-9. Crossref

20. Chua MS, Mok TS, Kwan WH, Yeo W, Zee B. Knowledge,

perceptions, and attitudes of Hong Kong Chinese women

on screening mammography and early breast cancer

management. Breast J 2005;11:52-6. Crossref

21. Schouten van der Velden AP, Peeters PH, Koot VC,

Hennipman A. Clinical presentation and surgical quality

in treatment of ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Acta

Oncol 2006;45:544-9. Crossref

22. Solin LJ, Fourquet A, Vicini FA, et al. Long-term outcome

after breast-conservation treatment with radiation for

mammographically detected ductal carcinoma in situ of

the breast. Cancer 2005;103:1137-46. Crossref

23. Habermann EB, Abbot A, Parsons HM, Virnig BA, Al-Refaie

WB, Tuttle TM. Are mastectomy rates really increasing in

the United States? J Clin Oncol 2010;28:3437-41. Crossref

24. Bihrmann K, Jensen A, Olsen AH, et al. Performance of

systematic and non-systematic (‘opportunistic’) screening

mammography: a comparative study from Denmark. J

Med Screen 2008;15:23-6. Crossref

25. Lui CY, Lam HS, Chan LK, et al. Opportunistic breast

cancer screening in Hong Kong; a revisit of the Kwong

Wah Hospital experience. Hong Kong Med J 2007;13:106-13.

26. Fisher B, Dignam J, Wolmark N, et al. Lumpectomy and

radiation therapy for the treatment of intraductal breast

cancer: findings from National Surgical Adjuvant Breast

and Bowel Project B-17. J Clin Oncol 1998;16:441-52.

27. Silverstein MJ, Lagios MD, Craig PH, et al. A prognostic

index for ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Cancer

1996;77:2267-74. Crossref

28. de Mascarel I, Bonichon F, MacGrogan G, et al. Application

of the Van Nuys prognostic index in a retrospective series of

367 ductal carcinomas in situ of the breast examined by

serial macroscopic sectioning: practical considerations.

Breast Cancer Res Treat 2000;61:151-9. Crossref

29. Staley H, McCallum I, Bruce J. Postoperative tamoxifen

for ductal carcinoma in situ: Cochrane systematic review

and meta-analysis. Breast 2014;23:546-51. Crossref

30. Yau TK, Sze H, Soong IS, et al. Surveillance mammography

after breast conservation therapy in Hong Kong:

effectiveness and feasibility of risk-adapted approach.

Breast 2008;17:132-7. Crossref