Hong Kong Med J 2016 Dec;22(6):623.e1–2

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj164889

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

PICTORIAL MEDICINE

Posterior facet talocalcaneal non-osseous coalition: an uncommon but easily missed cause

of hindfoot pain

Arnold YH Tsang, MB, BS, FRCR;

YY Cheuk, FHKCR, FHKAM (Radiology);

Andrea WS Au-Yeung, FHKCR, FHKAM (Radiology)

Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology, Kwong Wah

Hospital, Yaumatei, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Arnold YH Tsang (arnoldtsang@gmail.com)

A 50-year-old female presented with chronic hindfoot

pain in July 2015. She was treated for plantar fasciitis

but the pain remained unresolved. Radiographs were

initially interpreted as degenerative changes only.

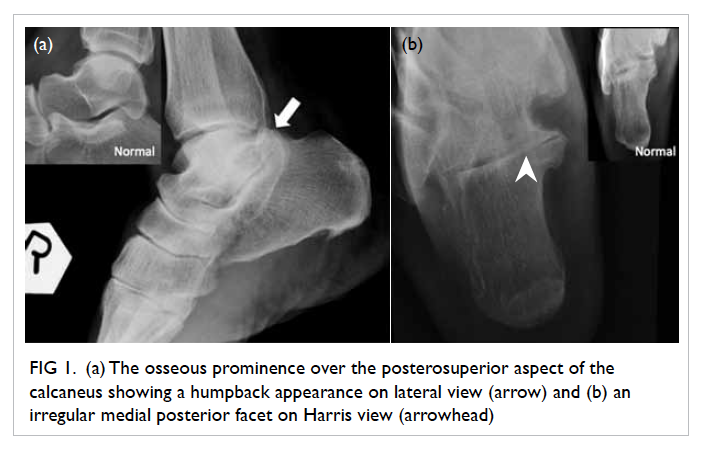

She was referred for further imaging. Review of the

radiographs showed an osseous prominence over the

posterosuperior aspect of the calcaneus, constituting

the abnormal shape of the posterior facet of the

subtalar joint with a humpback appearance on lateral

view (Fig 1a). Joint space of the medial posterior

facet was irregular and narrowed on Harris view

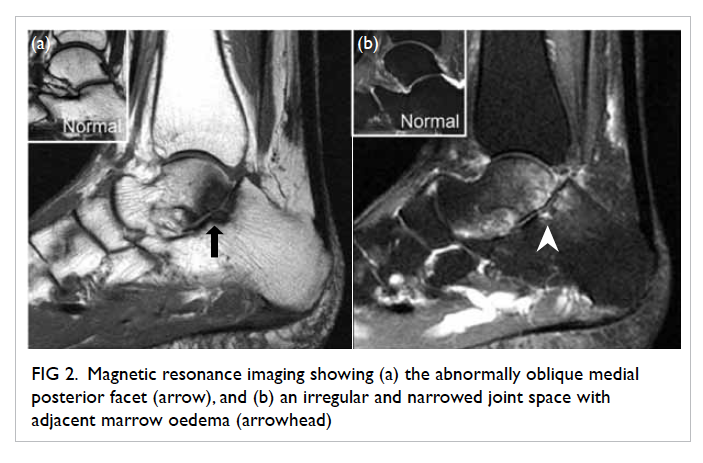

(Fig 1b). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed

the medial posterior facet of the subtalar joint to

be abnormally oblique on sagittal plane, and the

involved joint space was narrowed and irregular with

adjacent marrow oedema (Fig 2). No bony bridging

was seen. The middle facet was not involved. Included

tendons appeared unremarkable and plantar fascia

was not thickened. Features were suggestive of

fibrocartilaginous coalition at the medial aspect

of the posterior facet of the subtalar joint, also

referred to as posteromedial talocalcaneal coalition.

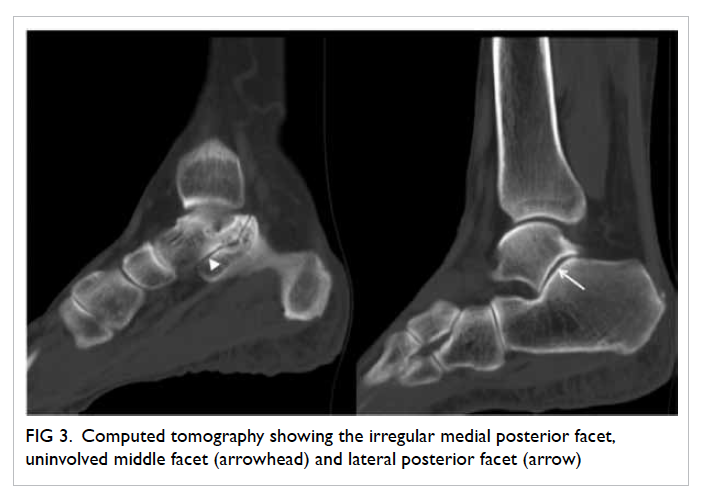

Computed tomography (CT) was also performed

for surgical planning, and demonstrated clearly the

irregular medial posterior facet, uninvolved middle

facet and lateral posterior facet (Fig 3).

Figure 1. (a) The osseous prominence over the posterosuperior aspect of the calcaneus showing a humpback appearance on lateral view (arrow) and (b) an irregular medial posterior facet on Harris view (arrowhead)

Figure 2. Magnetic resonance imaging showing (a) the abnormally oblique medial posterior facet (arrow), and (b) an irregular and narrowed joint space with adjacent marrow oedema (arrowhead)

Figure 3. Computed tomography showing the irregular medial posterior facet, uninvolved middle facet (arrowhead) and lateral posterior facet (arrow)

Tarsal coalition can be osseous or

fibrocartilaginous. Calcaneonavicular and

talocalcaneal coalition accounts for 90% of hindfoot

coalition,1 2 of which 50% are bilateral.1 The talocalcaneal joint, also referred to as the subtalar

joint, consists of anterior, middle, and posterior

facets. Talocalcaneal coalition usually involves the

middle facet at the level of the sustentaculum tali.

The incidence of middle facet coalition is less than

1%.1 3 Involvement of the posterior facet is even

rarer, and is an easily missed cause of hindfoot pain.

Continuous C sign is the classic sign well described

for coalition over the middle facet. For posterior facet

coalition, the humpback sign as described above is the

radiographic finding to be recognised.1 3 4 The medial

aspect of the posterior facet is more commonly

involved, and Harris view can better demonstrate

the medial joint that will be irregular and narrowed

in non-osseous coalition. These findings are easily

misinterpreted as degenerative changes.

Cross-sectional imaging including CT and

MRI are valuable to confirm the diagnosis, define

the location and extent of the segmentation

anomaly, look for associated complications, and aid

preoperative planning. In particular, CT is useful in

determining the presence of any small bony bridging

and is important for surgical planning; MRI is able

to provide information about the degree of marrow

oedema that may correlate with level of pain. It

should be remembered that any unexplained marrow

oedema around the subtalar joint, which is an atypical

site for simple degenerative changes, should raise

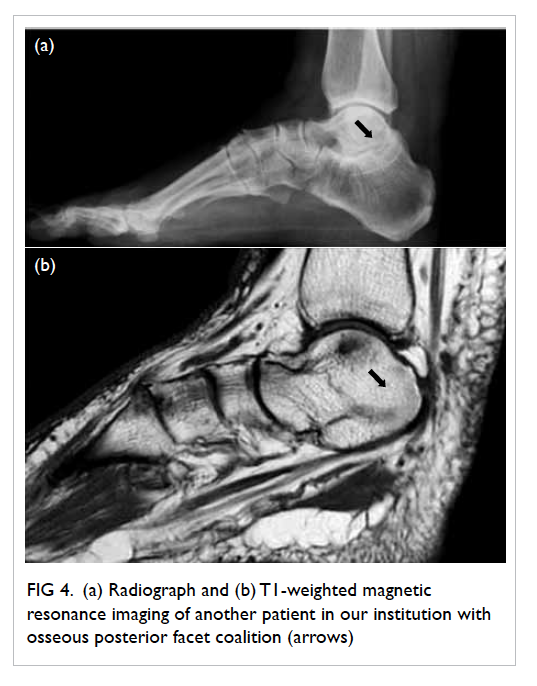

the suspicion of coalition. Osseous coalition is less

likely to be missed on cross-sectional imaging as it

will appear grossly abnormal with bony fusion across

the involved facet (Fig 4). Potential complications of posterior facet coalition include peroneus

muscle spasms, sinus tarsi syndrome, tarsal tunnel

compression giving rise to a distended posterior

tibial vein, calcaneal stress fracture, and premature

osteoarthritis.1 4 Early recognition of non-osseous

posterior facet talocalcaneal coalition is important,

particularly in young patients, as surgical treatment

can reduce complications later in life.

Figure 4. (a) Radiograph and (b) T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging of another patient in our institution with osseous posterior facet coalition (arrows)

References

1. Staser J, Karmazyn B, Lubicky J. Radiographic diagnosis

of posterior facet talocalcaneal coalition. Pediatr Radiol

2007;37:79-81. Crossref

2. Newman JS, Newberg AH. Congenital tarsal coalition:

multimodality evaluation with emphasis on CT and MR

imaging. Radiographics 2000;20:321-32. Crossref

3. McNally EG. Posteromedial subtalar coalition: imaging

appearances in three cases. Skeletal Radiol 1999;28:691-5. Crossref

4. Moe DC, Choi JJ, Davis KW. Posterior subtalar facet

coalition with calcaneal stress fracture. AJR Am J

Roentgenol 2006;186:259-64. Crossref