Hong Kong Med J 2016 Dec;22(6):582–8 | Epub 31 Oct 2016

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj164896

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Public knowledge of how to use an automatic external defibrillator in out-of-hospital cardiac

arrest in Hong Kong

KL Fan, MB, BS, FRCSEd1;

LP Leung, MB, BS, FRCSEd1;

HT Poon2;

HY Chiu2;

HL Liu2;

WY Tang2

1 Emergency Medicine Unit, Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

2 Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr LP Leung (leunglp@hku.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: The survival rate of out-of-hospital

cardiac arrest in Hong Kong is low. A long delay

between collapse and defibrillation is a contributing

factor. Public access to defibrillation may shorten this

delay. It is unknown, however, whether Hong Kong’s

public is willing or able to use an automatic external

defibrillator. This study aimed to evaluate public

knowledge of how to use an automatic external

defibrillator in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.

Methods: A face-to-face semi-structured

questionnaire survey of the public was conducted in

six locations with a high pedestrian flow in Hong Kong.

Results: In this study, 401 members of the public

were interviewed. Most had no training in first

aid (65.8%) or in use of an automatic external

defibrillator (85.3%). Nearly all (96.5%) would call

for help for a victim of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest

but only 18.0% would use an automatic external

defibrillator. Public knowledge of automatic external

defibrillator use was low: 77.6% did not know the

location of an automatic external defibrillator in

the vicinity of their home or workplace. People who

had ever been trained in both first aid and use of an

automatic external defibrillator were more likely to

respond to and help a victim of cardiac arrest, and to

use an automatic external defibrillator.

Conclusion: Public knowledge of automatic external

defibrillator use is low in Hong Kong. A combination

of training in first aid and in the use of an automatic

external defibrillator is better than either one alone.

New knowledge added by this study

- The prevalence of life-saving skills among Hong Kong citizens is low.

- Public knowledge of how to use an automatic external defibrillator is suboptimal.

- A programme that increases public access to an increased number of available automatic external defibrillators is unlikely to be successful without also improving public knowledge.

- Combining first aid training with automatic external defibrillator training is better than either one alone with regard to bystander basic life support and defibrillation skills.

Introduction

Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) is a major

cause of mortality globally.1 Despite major advances

in the field of resuscitation, the survival-to-hospital

discharge rate of OHCA in most regions is less than

10%.2 The crucial key lies in prehospital management.3

Research has shown that 53% of patients could be

in ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation

within 4 minutes of collapse in OHCA.4 Early

defibrillation in the prehospital phase is required

to terminate these rhythms and thus increase the

chance of survival. Based on the same rationale,

the strategy of public access defibrillation (PAD)

was introduced almost 20 years ago.5 There is now

increasing evidence that application of automatic

external defibrillator (AED) in communities by lay

bystanders improves survival following OHCA.6

Hong Kong has a population of about 7.3

million.7 As an international financial centre of

the world and a metropolis of China, Hong Kong

attracted nearly 61 million visitors from around the

world in 2014.8 The annual incidence of OHCA is

estimated to be 5000 to 6000. The survival rate for

non-traumatic OHCA to hospital discharge was

between 1.25% and 3.00%.9 10 11 This survival rate is

among the lowest compared with other Asian cities.12

Local studies have identified long time interval

between collapse and first defibrillation as one of the

factors contributing to the low survival rate.10 13 In

1995, in order to shorten the collapse to defibrillation

by first responder interval, AEDs were deployed in

ambulances in Hong Kong. In 2006, the Government

launched a PAD scheme whereby AED training was

provided to emergency responders, eg police officers

and other uniformed officers. Thereafter, AEDs

have been installed in various places in Hong Kong,

including public areas with a high public footfall. In

Hong Kong, neither cardiopulmonary resuscitation

nor use of an AED is a compulsory component of the

school curriculum. The first aid courses organised

by voluntary agencies may also not teach the use of

an AED. The number of laypersons trained in use of

an AED is unknown. It is also unknown whether a

layperson is willing or able to use the AED. Studies of

public knowledge about and attitudes to AED have

been conducted in the United States, Europe, and

Japan.14 15 16 There have been no similar investigations

in Hong Kong or other Chinese cities. This study

aimed to evaluate public knowledge about use of

an AED in OHCA in Hong Kong. Such data could

inform the health authorities when they are planning

local PAD programmes.

Methods

This study was a face-to-face semi-structured

questionnaire survey conducted on weekdays

between 2 November 2015 and 15 December

2015 (excluding Saturdays and public holidays).

The survey instrument was one adapted from an

investigation carried out in the United Kingdom.17

Two investigators performed the forward and

backward translation for the Chinese version to be

used in the survey. It consisted of three sections.

Section one collected demographic data. Questions

in sections 2 and 3 assessed the response to an

OHCA victim and knowledge of the use of an AED,

respectively.

The survey was conducted daily from 18:00 to

22:00 during the study period in six locations across

different districts of Hong Kong. Three locations

were in the vicinity of a mass transit railway (MTR)

station and the other three were close to a major

shopping centre. These spots were chosen to ensure

a high volume of pedestrians available for the

survey. All pedestrians at the location formed the

target population. One investigator from a team

of three medical students and one nursing student

approached the closest pedestrian, if possible one

chosen at random. All investigators were trained

how to administer the questionnaire in a standard

manner. After introduction of the research, informed

consent was obtained prior to completion of the

questionnaire. A pedestrian would be recruited for

the survey if he or she was aged 16 years or older

and a permanent resident of Hong Kong. The only

exclusion criterion was an inability to communicate

in Chinese or English. Each recruited subject was

asked for a response to each question, with no

prompting, to determine their response to a victim

in cardiac arrest and their knowledge of using an

AED. The whole survey took about 20 minutes.

No remuneration was received by the respondents.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review

Board of the University of Hong Kong/Hospital

Authority Hong Kong West Cluster (Reference

number: UW16-141).

The subject characteristics and their responses

are described by descriptive statistics. Comparison

was made between respondents who were and were

not trained in first aid, and between those who were

first aid–trained respondents with and without AED

training. Significance testing was done by Chi squared

test and Mann-Whitney U test where appropriate.

A P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Statistical analysis was performed by the Statistical

Package for the Social Sciences (Windows version

23.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago [IL], US). For sample size, to

attain a margin of error of 5% with a confidence level

of 95% regarding pedestrians’ response to an OHCA

victim (assumed to be 50% to maximise the sample

requirement), the minimum sample size was 385.

Results

During the study period, there were a total of

192 sessions (32 days x 6 spots); 733 pedestrians

were stopped and listened to the investigators’

introduction, and were invited for an interview at

one of the six locations. Overall, 42 did not fulfil the

inclusion criteria; 401 accepted the invitation and

completed the interview. On average, 3.8 pedestrians

per session were invited for an interview and 2.0

pedestrians per session completed the interview.

The response rate was 58% (401/691) with a slight

female predominance. Most were younger than 40

years and over half had attended university. The

majority of respondents had no training in first aid

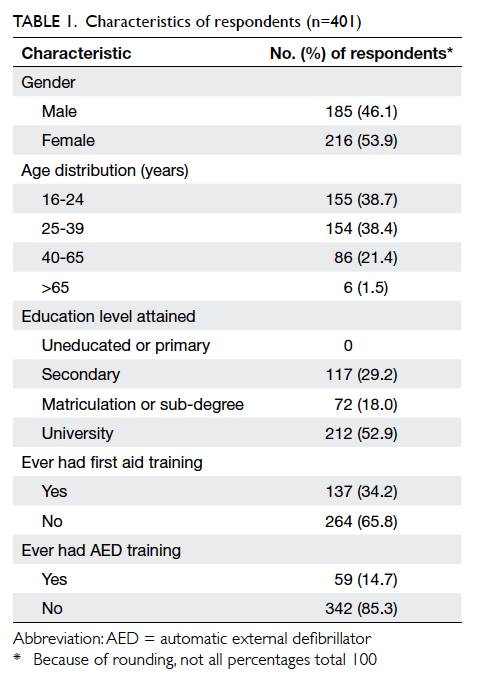

(65.8%) or use of an AED (85.3%) [Table 1]. Of the 137 subjects trained in first aid, 49 were also trained

in use of an AED. Although most respondents

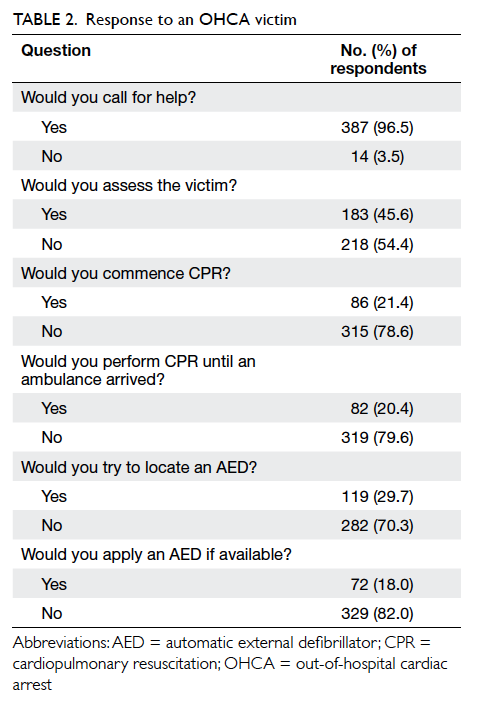

(96.5%) would summon help for a victim of OHCA,

only a minority of them were willing to do more,

eg perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation

(20.4%) or apply an AED (18.0%) [Table 2].

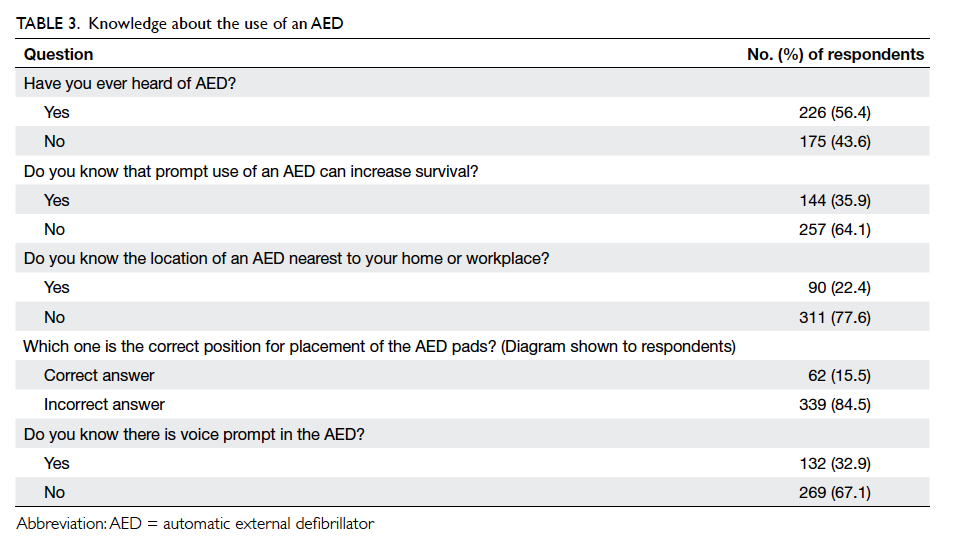

In general, knowledge about use of an AED

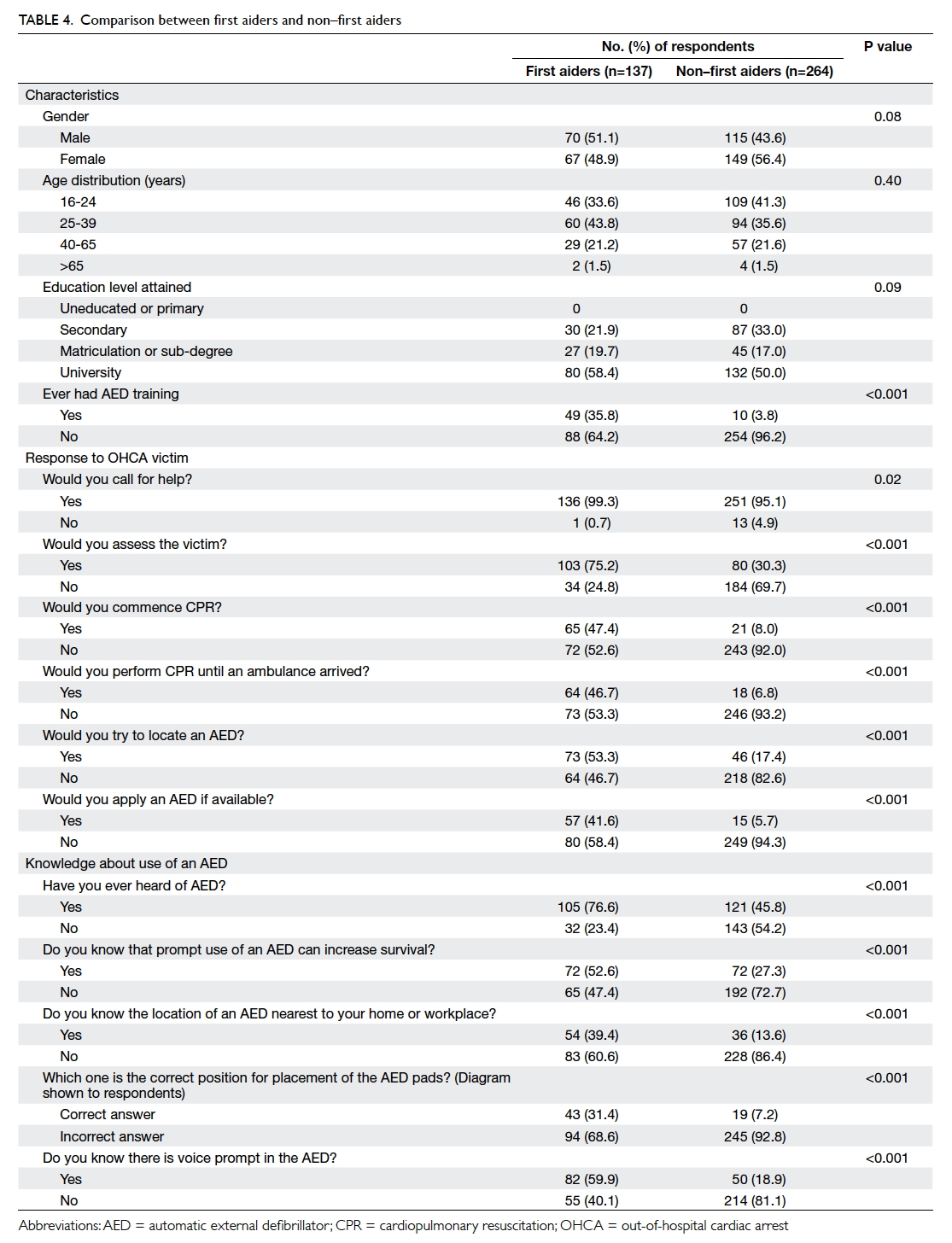

was suboptimal (Table 3). Comparison of first aiders with non–first aiders revealed that first aiders had

a more positive attitude in responding to a cardiac

arrest victim and were more knowledgeable about

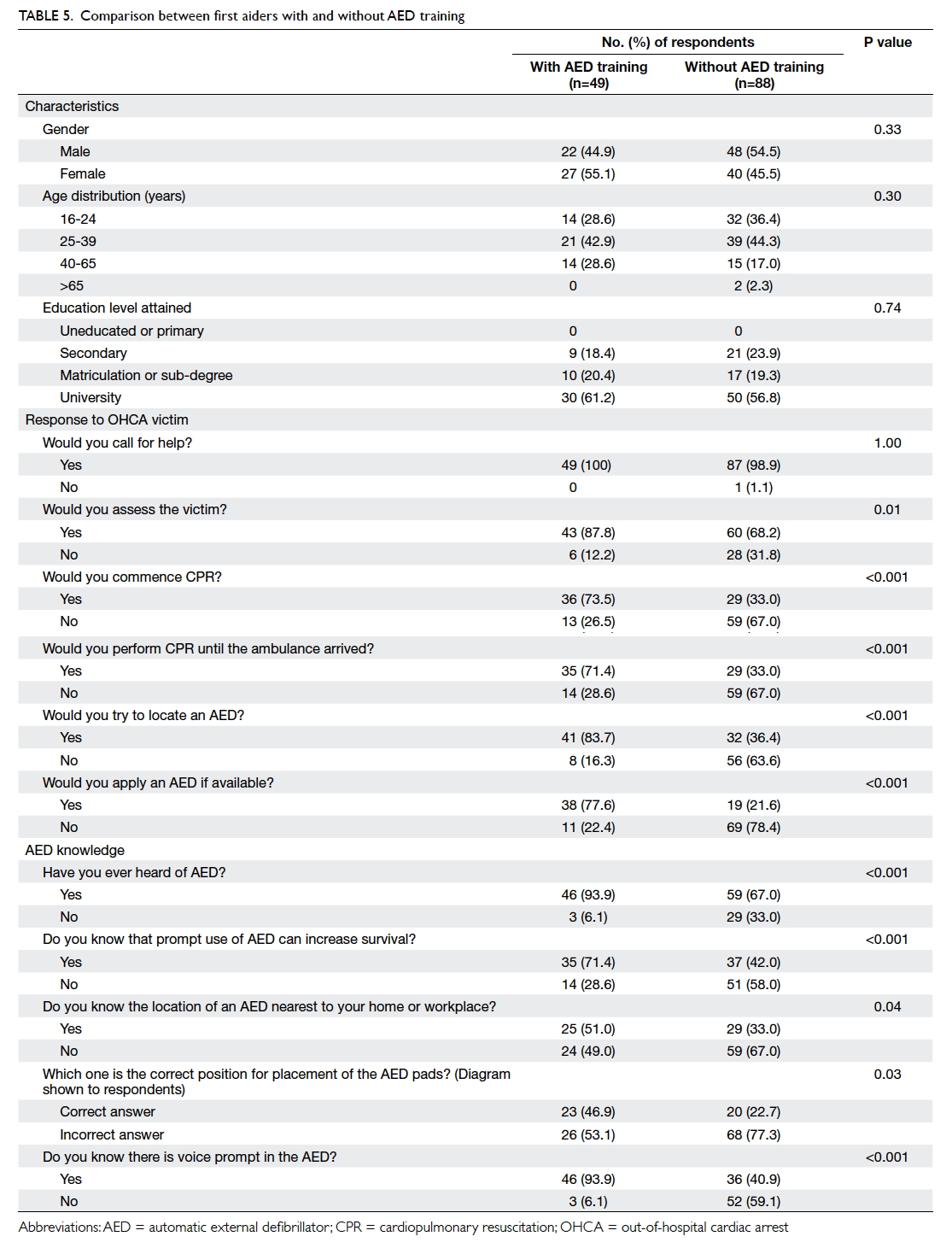

the use of an AED (Table 4). When first aiders with and without AED training were compared, those

with training were also more likely to respond to a

cardiac arrest victim, be more knowledgeable about

AED, and were more likely to try to locate an AED

and apply it (Table 5).

Discussion

The response rate of this study was only 58% among

those who stopped and listened to the investigators’

introduction. The exact cause for the apparently small

number of pedestrians being invited was unclear.

One of the possibilities included extra time being

spent in answering the queries of pedestrians and

thus the time left for invitation was reduced. Further,

part of the sessions fell within rush hour. Many

pedestrians, especially those at the MTR stations,

were in a hurry and reluctant to be interviewed.

This study revealed that approximately 34% of

respondents were trained in first aid. This percentage

is low in comparison to Sweden (45%), New Zealand

(74%), and Washington (79%) but comparable to

Singapore (31%).18 19 20 21 An even lower percentage

(approximately 15%) were trained in the use of

AED. Although subject recruitment and sampling

methods differed in these studies, both findings

from this study raise concern about the prevalence

of life-saving skills among Hong Kong citizens. It

is reasonable to postulate that an OHCA victim in

Hong Kong is less likely to receive life-saving support

by a bystander as most have received no training in

first aid or use of an AED. This is reflected by the

incongruity between the willingness to summon help

and reluctance to perform life-support procedures

for an OHCA victim. After calling for help for the

victim, most respondents would not try to locate an

AED or use it if available. These findings suggest that

there is an urgent need to implement community-based

education and training about sudden cardiac

arrest and basic life support, including the use of an

AED. The governments of many developed countries

have invested heavily in recent years to promote PAD

in their communities, eg the National Defibrillator

Programme in the United Kingdom.22 The results

of their efforts are encouraging with a significant

number of lives saved.

In this study, the high rate of reluctance to use an

AED may be explained by the suboptimal knowledge

of the respondents. They performed particularly

poorly in their knowledge of an AED location in the

vicinity of their home or workplace and the actual

operation of an AED. A comprehensive plan for

promoting PAD, with raising the public awareness of

the distribution of AED and teaching its operation

as a priority, is indicated in Hong Kong. Further,

because of the pervasiveness of mobile devices for

information and communication, use of mobile

apps to locate an AED may be useful. For example,

mobile apps using GPS (Global Positioning System)

technology to inform the potential responder to an

OHCA victim of the whereabouts of an AED have to

be explored. A Japanese study on the use of a mobile

AED map has shown promising results.23

Combined first aid and AED training seems

to be better than training in first aid alone. For first

aiders who were also trained in AED, they were more

likely to provide life-support intervention, including

the use of an AED, to an OHCA victim. For any

agency that organises first aid courses for the public,

the inclusion of AED training should be considered.

Limitations

This study is limited by the response rate of

approximately 58% that may be an overestimate as

the number of pedestrians refusing the invitation

right away were not included in the calculation. The

investigators were unable to obtain the characteristics

of the non-respondents for comparison. The

respondents included for analysis in this study

were relatively young and over half of them had

a university education. This casts doubt on the

representativeness of the sample. Representativeness

was also undermined by the adoption of convenience

sampling that is associated with selection bias of

subjects for interviews. Caution is thus required

when interpreting the results. Nonetheless it is

reasonable to suggest that people of older age or

with a lower education level are less likely to be

more knowledgeable about AED than the young or

those with a higher education level. Therefore, the

findings from this study may underestimate the lack

of knowledge about AED by the general public in

Hong Kong. An additional caution in interpretation

is information bias. Responses were self-reported

and not validated. The respondents may have given

what they considered to be socially desirable answers

to the interviewers.

Conclusion

Public knowledge of AED in Hong Kong is low.

Simply increasing the number of AED devices

installed is unlikely to be enough to increase its use

in OHCA victims. A territory-wide PAD programme

that couples first aid training with AED training may

increase the use of AED in OHCA victims in Hong

Kong. Use of mobile information technology, eg an

AED locator app, should also be explored.

Declaration

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Nichol G, Thomas E, Callaway CW, et al. Regional variation in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest incidence and outcome. JAMA 2008;300:1423-31. Crossref

2. Berdowski J, Berg RA, Tijssen JG, Koster RW. Global

incidences of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and survival rates: Systematic review of 67 prospective studies. Resuscitation 2010;81:1479-87. Crossref

3. McNally B, Robb R, Mehta M, et al. Out-of-hospital cardiac

arrest surveillance—Cardiac Arrest Registry to Enhance Survival (CARES), United States, October 1, 2005—December 31, 2010. MMWR Surveill Summ 2011;60:1-19.

4. Herlitz J, Ekström L, Wennerblom B, Axelsson A, Bång A,

Holmberg S. Type of arrhythmia at EMS arrival on scene in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in relation to interval from collapse and whether a bystander initiated CPR. Am J Emerg Med 1996;14:119-23. Crossref

5. Weisfeldt ML, Kerber RE, McGoldrick RP, et al.

Public access defibrillation. A statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association Task

Force on Automatic External Defibrillation. Circulation 1995;92:2763. Crossref

6. Weisfeldt ML, Sitlani CM, Ornato JP, et al. Survival after

application of automatic external defibrillators before arrival of the emergency medical system: evaluation in

the resuscitation outcomes consortium population of 21 million. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;55:1713-20. Crossref

7. Census and Statistics Department, Hong Kong SAR

Government. Population. 2014. Available from: http://www.censtatd.gov.hk/hkstat/sub/so20.jsp. Accessed 5 Jan 2016.

8. Tourism Commission, Commerce and Economic Development Bureau, Hong Kong SAR Government. Tourism performance in 2014. Available from: http://www.tourism.gov.hk/english/statistics/statistics_perform.html. Accessed 5 Jan 2016.

9. Wong TW, Yeung KC. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: two

and a half years experience of an accident and emergency

department in Hong Kong. J Accid Emerg Med 1995;12:34-9. Crossref

10. Lui JC. Evaluation of the use of automatic external

defibrillation in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in Hong

Kong. Resuscitation 1999;41:113-9. Crossref

11. Leung LP, Wong TW, Tong HK, Lo CB, Kan PG. Out-of-hospital

cardiac arrest in Hong Kong. Prehosp Emerg Care

2001;5:308-11. Crossref

12. Ong ME, Shin SD, De Souza NN, et al. Outcomes for

out-of-hospital cardiac arrests across 7 countries in Asia:

The Pan Asian Resuscitation Outcomes Study (PAROS).

Resuscitation 2015;96:100-8. Crossref

13. Fan KL, Leung LP. Prognosis of patients with ventricular

fibrillation in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in Hong Kong:

prospective study. Hong Kong Med J 2002;8:318-21.

14. Kozłowski D, Kłosiewicz T, Kowalczyk A, et al. The

knowledge of public access to defibrillation in selected

cities in Poland. Arch Med Sci 2013;9:27-33. Crossref

15. Taniguchi T, Sato K, Kurita A, Noda T, Okajima M.

Attitudes toward automated external defibrillator use in

Japan in 2011. J Anesth 2014;28:34-7. Crossref

16. Gonzalez M, Leary M, Blewer AL, et al. Public knowledge

of automatic external defibrillators in a large U.S. urban

community. Resuscitation 2015;92:101-6. Crossref

17. Brooks B, Chan S, Lander P, Adamson R, Hodgetts GA,

Deakin CD. Public knowledge and confidence in the use of

public access defibrillation. Heart 2015;101:967-71. Crossref

18. Axelsson AB, Herlitz J, Holmberg S, Thorén AB. A

nationwide survey of CPR training in Sweden: foreign born

and unemployed are not reached by training programmes.

Resuscitation 2006;70:90-7. Crossref

19. Larsen P, Pearson J, Galletly D. Knowledge and attitudes

towards cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the community.

N Z Med J 2004;117:U870.

20. Sipsma K, Stubbs BA, Plorde M. Training rates and

willingness to perform CPR in King County, Washington: a

community survey. Resuscitation 2011;82:564-7. Crossref

21. Ong ME, Quah JL, Ho AF, et al. National population based

survey on the prevalence of first aid, cardiopulmonary

resuscitation and automated external defibrillator skills in

Singapore. Resuscitation 2013;84:1633-6. Crossref

22. UK Department of Health. National Defibrillator

Programme. 2010. Available from: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/www.dh.gov.uk/en/Healthcare/Longtermconditions/Vascular/Coronaryheartdisease/Coronarypromotionproject/index.htm. Accessed 1 Feb 2016.

23. Sakai T, Iwami T, Kitamura T, et al. Effectiveness of the

new ‘Mobile AED Map’ to find and retrieve an AED: A

randomised controlled trial. Resuscitation 2011;82:69-73. Crossref