Hong Kong Med J 2016 Dec;22(6):576–81 | Epub 24 Oct 2016

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj164970

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Sexual violence cases in a hospital setting

in Hong Kong: victims’ demographic, event

characteristics, and management

WK Chiu, MB, ChB, MRCOG1;

WC Lam, MRCOG, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)1;

NH Chu, MRCP (UK), FHKAM (Emergency Medicine)2;

Charles KM Mok, FRCOG, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)1;

WK Tung, FRCSEd, FHKAM (Emergency Medicine)2;

Frances YL Leung, FHKAM (Emergency Medicine)3;

SM Ting, FRCSEd, FHKAM (Emergency Medicine)3

1 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, United Christian Hospital, Kwun Tong, Hong Kong

2 Department of Accident and Emergency, Kwong Wah Hospital, Yaumatei,

Hong Kong

3 Department of Accident and Emergency, United Christian Hospital, Kwun Tong, Hong Kong

This paper was presented at the 2015 Western Pacific Regional

Conference of Medical Women’s International Association, 24-26 April

2015, Taipei, Taiwan.

Corresponding author: Dr WC Lam (lam_mona@hotmail.com)

Abstract

Introduction: Rainlily, the first one-stop crisis

centre in Hong Kong, was set up in 2000 to protect

female victims of sexual violence. This study aimed

to analyse the characteristics of sexual assault cases and victims

who presented to two hospitals

in Hong Kong. The data are invaluable for health care

professionals and policymakers to improve service

provision to these victims.

Methods: This retrospective analysis of hospital

records was conducted in two acute hospitals under

the Hospital Authority in Hong Kong. Sexual assault

victims who attended the two hospitals between May

2010 and April 2013 were included. Characteristics

of the cases and the victims, the use of alcohol and

drugs, involvement of violence, and the outcome of

the victims were studied.

Results: During the study period, 154 sexual assault

victims attended either one of the two hospitals.

Their age ranged from 13 to 64 years. The time from

assault to presentation ranged from 1 hour to more

than 5 months. Approximately 50% of the assailants

were strangers. Approximately 50% of victims

presented with symptoms; the most common were

pelvic and genitourinary symptoms. Those with

symptoms (except pregnancy) presented earlier than

those without. The use of alcohol and drugs was

involved in 36.4% and 11.7% of cases, respectively.

Approximately 10% of the screened victims were

positive for Chlamydia trachomatis. There were

11 pregnancies with gestational age ranged from

6 weeks to 5 months at presentation. Less than half

of the victims completed follow-up care.

Conclusions: Involvement of alcohol and drugs is

not uncommon in sexual assault cases. Efforts should

be made to promote public education, enhance coordination

between medical and social services, and

improve the accessibility and availability of clinical

care. Earlier management and better compliance with

follow-up can minimise the health consequences

and impact on victims.

New knowledge added by this study

- A significant proportion of sexual assault cases involved the use of alcohol (36.4%) or drugs (11.7%). This number may be underreported. Physical violence with or without verbal threat was reported in approximately 30% of cases. Half of the victims attended hospital more than 3 days after the incident when emergency contraception would be less effective.

- Blood and urine samples for toxicology screening should be obtained in selected sexual assault cases. Public education should focus on primary prevention, the means of seeking help, and the importance of early medical care. A territory-wide case review may offer a better evaluation of the problem in Hong Kong.

Introduction

Sexual violence refers to sexual activity where

consent is not obtained or freely given.1 The World

Health Organization defines sexual violence as “any

sexual act, attempt to obtain a sexual act, or other act

directed against a person’s sexuality using coercion,

by any person regardless of their relationship to the

victim, in any setting”.2 This includes rape, indecent

assault, sexual harassment and threats. According

to the statistics of ‘Child abuse, spouse/cohabitant

battering and sexual violence cases’ from the

Social Welfare Department, the majority (88.4%) of

newly reported sexual violence cases in Hong Kong

are indecent assault and 8.8% are rape or unlawful

sexual intercourse. More than 96% of the victims are

females. Approximately 70% of the perpetrators are

strangers, and the rest are usually someone known to

the victim, such as a family member, friend, lover or

ex-lover, co-worker, caregiver, neighbour, or teacher.3

Sexual violence is usually underreported because

of fear: fear of physical examination, disclosure of

sexual history, repeating the traumatic experience

in full detail over and over again, complicated legal

procedures, not being believed by others, and being

harmed by the perpetrator(s).2

Sexual violence may lead to health consequences

such as unwanted pregnancy, sexually transmitted

disease (STD) infections, physical trauma,

depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder.4

Not all victims will seek medical care, however,

because the experience of sexual violence is seen as

stigmatising and shameful, with possible extreme

social consequences.5 Stigmatisation not only from

society but also from health care providers, family,

and even the intimate partner is common. This leads

to minimal support for the victims who may distance

themselves by withdrawing from social activities.6

In November 2000, the Association Concerning

Sexual Violence Against Women set up the first one-stop

crisis centre in Hong Kong, Rainlily, for the

protection of female victims of sexual violence. All

the social workers at Rainlily are female and trained

to provide counselling and care for victims of sexual

assault. They will accompany the victim for medical

care, police interviews, legal proceedings, and most

importantly, the possibly long and difficult recovery

period from the incident.

For many years, Rainlily has worked with the

accident and emergency department of Kwong Wah

Hospital to provide one-stop service to victims

of sexual violence including pregnancy prevention,

screening and prevention of STDs, forensic medical

examination, psychological support, and reporting

to the police if desired by the victim. This avoids

recalling and repeating the unpleasant experience

for different professionals and hence minimises

the need for the victim to psychologically re-live

the trauma. Since May 2010, Rainlily has also

collaborated with the United Christian Hospital and

set up an additional rape crisis centre.

We conducted a retrospective analysis of

female victims of sexual assault who were seen at

either hospital to evaluate the characteristics of

the cases and the victims, the use of alcohol and

drugs, involvement of violence, and the outcome

of the victims. The data are invaluable for health care

professionals and policymakers for improving

service provision for victims.

Methods

All female sexual assault victims who attended the

Kwong Wah Hospital or United Christian Hospital

from May 2010 to April 2013 were included in this

retrospective study. The sexual assault cases were

identified from the special case list of the accident

and emergency department of each hospital and

the designated gynaecology clinic booking list of

the United Christian Hospital. The clinical records

were reviewed and the demographics of the victims,

time lapse from assault to presentation at hospital,

characteristics of the assault, investigations and

results, treatment and outcome of the victims were

analysed.

At Kwong Wah Hospital, the sexual assault

cases were managed and followed up in the accident

and emergency department, with referral to

gynaecologists if clinically indicated, for example,

for unwanted pregnancy. At the United Christian

Hospital, cases were initially managed in the accident

and emergency department with subsequent follow-up

in the gynaecology clinic. At initial presentation,

victims were screened for the presence of any

infection, including STDs. Emergency contraception

was prescribed if necessary. Subsequent follow-up

was after 2 weeks, 6 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months

to exclude pregnancy, to review investigation results

and treat any infection.

The study protocol complied with the

good clinical practice of ICH (The International

Conference on Harmonisation of Technical

Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals

for Human Use). Ethical approval was obtained from

Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Hospital Authority.

All statistical analysis of data was performed

by PASW Statistics 18, Release Version 18.0.0 (SPSS,

Inc, 2009, Chicago [IL], US). For continuous data

with a highly skewed distribution such as time from

the incident of assault to presentation at the hospital,

Mann-Whitney U test was used. The critical level of

statistical significance was set at 0.05.

Results

Demographics of victims

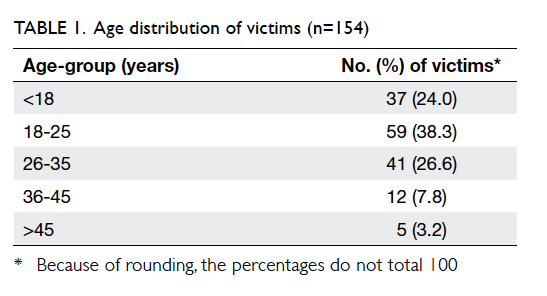

From May 2010 to April 2013, a total of 154 sexual

assault victims had attended either hospital; 102 at

Kwong Wah Hospital and 52 at United Christian

Hospital. The age of victims ranged from 13 to 64

years (mean 24.5 years, median 22 years; Table 1). Most (150 cases; 97.4%) victims were Chinese and four were domestic helpers from other Asian

countries. Five (3.2%) victims were mentally disabled

and 19 (12.3%) had a history of psychiatric disorder.

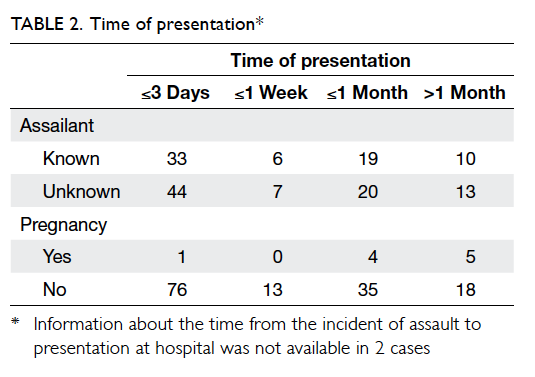

Time between assault and presentation

The time from the incident of assault to presentation

at the hospital ranged from 1 hour to more than 5

months (mean 16 days, median 3 days). Half of the

victims (n=77) attended hospital within 3 days of

the incident. Approximately half (n=84, 54.5%) of

the assailants were strangers (Table 2); the others

included friend, internet friend, family member,

classmate, colleague, employer, boyfriend, ex-boyfriend,

and ex-husband.

The median time from the incident to

presentation was 48 hours (interquartile range

[IQR], 24-240 hours) for victims with symptoms

(except pregnancy), compared with 288 hours for

those without (IQR, 48-696 hours) [P<0.001]. Those

who were pregnant (median time, 756 hours; IQR,

510-1386 hours) presented later than those who

were not (median time, 72 hours; IQR, 24-432 hours)

[P<0.001].

Characteristics of the incident

In 56 (36.4%) cases, alcohol was involved in the

incident. There were 18 (11.7%) cases where drugs

were involved, including ketamine, amphetamine,

methamphetamine, cocaine, and midazolam. In one

victim, multiple drugs were involved. Some victims

could not identify which drug they had been given. It

had either been added to the victim’s drink, or been

given as ‘flu medication’ or an ‘anti-drunk pill’.

There were 133 (86.4%) victims with

documented vaginal penetration, of whom 25

had also been exposed to oral penetration, five

to anal penetration, and four to all three forms of

sexual assault. There were three victims in whom

penetration was oral only. The remaining 18 victims

had no clear documentation. In only three (1.9%)

cases did the assailant use a condom. Verbal threats

were reported by six (3.9%) victims, and physical

violence with or without verbal threat by 45 (29.2%).

Reported physical violence included restraint,

strangling, beating, grasping, and biting.

Presenting symptoms

Apart from the incident, 75 (48.7%) victims presented

with other associated problems, most (n=44, 28.6%)

with pelvic or genitourinary symptoms such as

lower abdominal pain, vaginal discharge, or urinary

symptoms. There were 17 (11.0%) victims who

complained of laceration, contusions, bruises, and

pain due to physical violence during the incident.

Another 12 (7.8%) victims presented with psychiatric

or mood problems: two attempted suicide, one had

auditory hallucinations, and the others had mood

problems or post-traumatic stress disorder with

nightmares and flashbacks. One victim presented

with per rectal bleeding due to anal penetration and

another presented with recurrent oral ulcers in which

oral penetration was involved during the incident.

Seven victims had found themselves pregnant before

attending the hospital.

Sexually transmitted diseases

Blood testing for hepatitis B surface antigen was

performed in 146 victims of whom six (4.1%) were

positive. All positive results were obtained within

6 weeks of the sexual assault. Hepatitis B surface

antibodies were not present in 85 of 134 victims

tested. Hepatitis B immunoglobulin was given to 43

victims and a first dose of hepatitis B vaccination to

52. Only 29 victims completed the course of hepatitis

B vaccination, however, and the remainder defaulted

from follow-up.

Blood test for syphilis by rapid plasma reagin

was positive in one victim and was performed

around 4 days after the sexual assault. Treponema

pallidum haemagglutination assay was also positive.

There was no other positive case in the subsequent

screening at 6 weeks and 6 months. A similar result

was obtained when testing for anti–hepatitis C

virus antibody that was positive in one victim and

the test was performed within 1 day of the sexual

assault. There was no other positive case identified

at subsequent follow-up. Blood tests for anti–human

immunodeficiency virus antibody were all negative

and a total of 71 victims had negative serology 6

months after the alleged assault.

High vaginal and endocervical swabs were

taken for culture and revealed one victim with

Trichomonas vaginalis. Urethral, rectal, and throat

swabs were taken in selected cases and no infection

other than with Candida species was detected.

Chlamydia trachomatis was tested by polymerase

chain reaction test on a urine sample or endocervical

swab in 110 victims, and 12 (10.9%) were positive.

Among those with chlamydial infection, four

presented with genitourinary symptoms such as

perineal pain, vaginal discharge, urinary frequency,

and dysuria.

Pregnancy

Emergency contraception was provided to 63 of the

77 victims who presented within 3 days of the alleged

rape. There were 10 victims who had been prescribed

emergency contraception, either by other doctors, or

self-prescribed from a pharmacy. Other reasons for

not prescribing emergency contraception included a

victim with only oral penetration, one victim with

a previous hysterectomy, two victims taking reliable

regular contraception, and one victim who refused

the prescription.

There were a total of 11 pregnancies as a result

of the incident, among them one victim had received

emergency contraception within the day of assault.

The gestational age ranged from 6 weeks to 5 months

at presentation. Eight cases underwent termination

of pregnancy, one underwent medical evacuation for

silent miscarriage, one continued the pregnancy

to term, and one defaulted from follow-up with

unknown outcome.

Attendance at follow-up

Attendance at follow-up was 57.8%, 63.6%, 59.1% and

46.8% at 2 weeks, 6 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months,

respectively after the incident. Overall, less than half

of the victims completed follow-up care.

Discussion

Every 2 to 3 minutes, one woman is sexually assaulted

somewhere in the world.7 The prevalence of sexual

violence differs across populations, but studies have

consistently shown there to be underreporting

in both developed and developing countries.5 It is

believed that Hong Kong is no different. The reported

cases may only be the tip of the iceberg. This makes

prevention, detection, and proper care difficult.

Comparison with a similar study conducted

in Hong Kong from 2001 to 2004 by Chu and Tung8

shows that the age of victims, time between assault

and presentation, and the percentage of those lost

to follow-up are similar; thus the characteristics

appear unchanged over the past decade. This raises

the question of whether we are doing enough to

promote awareness, prevention, and education in

society.

A considerable proportion of victims have a

history of psychiatric disorder, and there is emerging

evidence of the association.9 Although the causal

relationship is not well understood, it might be due

to the higher prevalence of alcohol or substance

abuse among this population. Nonetheless, a history of

alcohol or substance abuse was not always documented

in the case notes. Patients having a certain type of

psychiatric disorder—such as schizophrenia, bipolar

disorder, and heroin addiction—are more likely to

adopt risky behaviour,10 and hence are at higher risk

of being sexually abused.

The delayed presentation among victims of

assault by a known assailant may be due to the fear of

being discovered by the assailant and being further

harmed. Furthermore, sexual violence is associated

with stigma in some communities, even in cases

with an unknown assailant; the victims may be

afraid of being blamed, and there is also a perceived

lack of support from families and friends.11 Delayed

presentation may result in loss of forensic evidence,

delay in prescription of STD prophylaxis, and a

missed chance for emergency contraception.12 This

explains why those who were pregnant presented

later than those who were not, and those without

symptoms may not have sought help until they found

themselves pregnant. Public education definitely

has a role and must emphasise the importance of

seeking medical care early and promote community

awareness of prevention, instead of blaming the victims.

The prevalence of sexual assault involving

alcohol or drug use in this study was similar to a

previous study by Hurley et al.13 Females are more

vulnerable to the effects of alcohol because of their

smaller body mass and higher proportion of body

fat. Compared with drugs, there is a higher rate of

alcohol involvement in sexual assault cases because

it is easily available, cheap, and legally and socially

acceptable. Alcohol can cause disinhibition and

impair judgement; most of the victims consumed

alcohol voluntarily and therefore there is a strong

feeling of self-blame after the incident. Recreational

drugs consumed by victims themselves or ‘date rape

drug’–spiked drinks given to victims can cause

sedation, anterograde amnesia, and incapacitation.

The actual prevalence is likely to be more than

reported, as the victims may not be aware of the

assault or only have patchy recall of events. Some

of these victims have an intense fear of internet

exposure of their body or the incident, and feel a loss

of control and sense of insecurity. If a drug abuser

is assaulted, they may worry about being charged

and are reluctant to report the incident to the police.

Delay in reporting or seeking help results in loss

of forensic evidence and delay in prescription of

emergency contraception. The current protocol of

the two studied units did not include toxicological

analysis. Therefore the drug used was based on the

victim’s report and recall error is highly likely. In

order to improve service provision and to help in

crime recollection, blood, urine, and nasal swabs for

toxicology screening should be obtained in selected

sexual assault cases. Public education should

emphasise the harmful effects of excessive alcohol

consumption and the effects of combining alcohol

and recreational drugs. Ways to avoid spiked drinks

include keeping an eye on one’s drink, not leaving a

drink unattended or obtaining a new one if it is, and

not accepting a drink from strangers.

The most common presenting symptoms

were pelvic and genitourinary symptoms or

injuries as a result of violence during the incident.

Psychiatric symptoms were usually underreported.

Common symptoms include low mood, fear, guilt,

nervousness, sleeping difficulties, poor appetite, and

feelings of shame and anger. Emotional numbness

and avoidance are common reasons for not seeking

help.14 Moreover, some medical providers do not

actively ask about psychiatric symptoms. Even if

symptoms are reported, they may be considered a

‘normal reaction’ to rape and then ignored. About half

of victims recover from acute psychological effects

by 12 weeks, but in others the symptoms persist

for years.14 Sexual assault survivors are at increased

lifetime risk of post-traumatic stress disorder, major

depression, suicidal ideas and attempts.15 Mental

state and risk of self-harm should be assessed to

identify those who are at risk. Psychosocial support

and opportunities to talk about the incident are

important. For those who do not recover with time,

referral to a psychotherapist or even a psychiatrist is

essential.

Some experts discourage testing for STD

infections in the acute setting unless clinically

indicated by symptoms.15 The positive rate of STD in

this study was low with the exception of chlamydial

infection. Nucleic acid amplification testing can be

carried out on urine samples instead of endocervical

samples, minimising the need for invasive vaginal

examination using a speculum.14 One may consider

omitting the screening test and instead offering

prophylactic antibiotics against bacterial STDs.

The rate of pregnancy (7.1%) is slightly higher

than the quoted risk of 5%.16 The administration

of emergency contraception in the two studied

units comes in the form of levonorgestrel and was

limited to victims who presented within 3 days of

alleged rape. Levonorgestrel is licensed for up to 72

hours after unprotected intercourse, indeed there is

still some residual efficacy after 3 days although it

diminishes with time. To further decrease the chance

of pregnancy, other contraceptive methods can be

considered in victims who present more than 3 days

after the incident, including a copper intrauterine

device or ulipristal acetate. If it is not feasible to

insert an intrauterine device in the emergency

department, urgent referral to a gynaecology clinic

should be considered. Ulipristal acetate may not be

readily available in all public hospitals but it could be

stocked and prescribed as a patient-financed item.

Limitations of this study include the small

sample size, recall bias of alcohol or drug use, loss

of some victims to follow-up, and short follow-up

periods. A territory-wide case review may offer a

better evaluation of the problem in Hong Kong.

Conclusions

Sexual assault is usually underreported and can

lead to significant health consequences. Involvement

of alcohol and drugs is not uncommon in sexual

assault cases. Efforts should be made to enhance coordination

and cooperation between medical and

social services, and improve the accessibility and

availability of clinical care. Health care professionals

should be properly trained to understand the physical

and mental health consequences, the importance of follow-up care, and to equip the skills to manage sexual assault cases. Public education should target at primary prevention, and publicise the simple ways to access the available services.

Acknowledgement

The authors gratefully acknowledge Mr Edward Choi

for his valuable statistical advice.

Declaration

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Understanding sexual violence. National Center for Injury

Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention; 2012.

2. Violence against women: preventing intimate partner and

sexual violence against women. Geneva: World Health

Organization; 2011.

3. Statistics on child abuse, spouse/cohabitant battering and

sexual violence cases. Social Welfare Department, the

Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative

Region; 2014.

4. Welch J, Mason F. Rape and sexual assault. BMJ

2007;334:1154-8. Crossref

5. Dartnall E, Jewkes R. Sexual violence against women: the

scope of the problem. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol

2013;27:3-13. Crossref

6. Jina R, Thomas LS. Health consequences of sexual violence

against women. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol

2013;27:15-26. Crossref

7. Masho SW, Odor RK, Adera T. Sexual assault in Virginia:

A population-based study. Womens Health Issues

2005;15:157-66. Crossref

8. Chu LC, Tung WK. The clinical outcome of 137 rape

victims in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J 2005;11:391-6.

9. Goodman LA, Rosenberg SD, Mueser KT, Drake RE.

Physical and sexual assault history in women with serious

mental illness: prevalence, correlates, treatment, and

future research directions. Schizophr Bull 1997;23:685-96. Crossref

10. Hariri AG, Karadag F, Gokalp P, Essizoglu A. Risky

sexual behavior among patients in Turkey with bipolar

disorder, schizophrenia, and heroin addiction. J Sex Med

2011;9:2284-91. Crossref

11. Abrahams N, Devries K, Watts C, et al. Worldwide

prevalence of non-partner sexual violence: a systematic

review. Lancet 2014;383:1648-54. Crossref

12. McCall-Hosenfeld JS, Freund KM, Liebschutz JM. Factors

associated with sexual assault and time to presentation.

Prev Med 2009;48:593-5. Crossref

13. Hurley M, Parker H, Wells DL. The epidemiology of drug

facilitated sexual assault. J Clin Forensic Med 2006;13:181-5. Crossref

14. Cybulska B. Immediate medical care after sexual assault.

Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2013;27:141-9. Crossref

15. Linden JA. Clinical practice. Care of the adult patient after

sexual assault. N Engl J Med 2011;365:834-41. Crossref

16. Holmes MM, Resnick HS, Kilpatrick DG, Best CL. Rape-related

pregnancy: estimates and descriptive characteristics

from a national sample of women. Am J Obstet Gynecol

1996;175:320-4. Crossref