Hong Kong Med J 2016 Dec;22(6):570–5 | Epub 24 Oct 2016

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj164930

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Factors affecting the deceased organ donation rate in the Chinese community: an audit of

hospital medical records in Hong Kong

CY Cheung, PhD, FHKAM (Medicine)1;

ML Pong, BSc (Nursing)2;

SF Au Yeung, BSc (Nursing)2;

KF Chau, FRCP, FHKAM (Medicine)1

1 Department of Medicine, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Jordan, Hong Kong

2 Transplant Coordinating Service, Kowloon Central Cluster, Hospital Authority, Hong Kong

2 Transplant Coordinating Service, Kowloon Central Cluster, Hospital Authority, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr CY Cheung (simoncycheung@gmail.com)

Abstract

Introduction: The number of actual donors per

million population is the most commonly used

metric to measure organ donation rates worldwide.

It is deemed inadequate, however, because it does

not take into account the potential donor pool. The

aim of this study was to determine the true potential

for solid organ donation from deceased brain-dead

donors and the reasons for non-donation from

potential donors in the Chinese community.

Methods: Medical records of all hospital deaths

between 1 January and 31 December 2014 at a large

regional hospital in Hong Kong were reviewed.

Those who were on mechanical ventilation with

documented brain injury and aged ≤75 years

were classified as possible organ donors. The reasons

why some potential organ donors did not become

utilised organ donors were recorded and evaluated.

Results: Among 3659 patient deaths, 121 were

classified as possible organ donors. The mean age of the possible organ donors

was 59.4 years and 72.7% of them were male. The majority

(88%) were from non–intensive care units. Of the

121 possible organ donors, 108 were classified as

potential organ donors after excluding 13 unlikely to

fulfil brain death criteria. Finally 11 patients became

actual organ donors with an overall conversion rate

of 10%. Reasons for non-donation included medical

contra-indication (46%), failure to identify and

inform organ donation coordinators (14%), failure of

donor maintenance (11%), brain death diagnosis not

established (18%), and refusal by relatives (11%).

Conclusions: It is possible to increase the organ

donation rate considerably by action at different

stages of the donation process. Ongoing accurate

audit of current practice is necessary.

New knowledge added by this study

- There are different areas in the donation process where it may be possible to increase the organ donation rate considerably. Failure of health care professionals to identify potential donors is considered to be an important contributing factor to the shortage of cadaver organs in our community.

- All potential donors should be considered for referral to the intensive care unit for possible admission and physiological support through to brain death.

Introduction

Organ transplantation is considered to be the best

treatment for patients having end-stage organ failure.

There is a global shortage of organs, however. In the

United States, more than 100 000 potential recipients

are waiting for organs of whom only one fourth will

ultimately undergo organ transplantation.1 In a

systematic medical review, Jansen et al2 showed that

the maximum number of potential organ donors can

be approximately 3 times higher than the number of

effective organ donors. As a result, understanding

the pitfalls at each step of the process of organ

procurement, starting from donor identification to

retrieval of organs, is extremely important in the

evaluation of the size of the potential donor pool.

The number of actual donors per million

population (pmp) is the most commonly used metric

to measure organ donation rates and performances

in different countries. It has been deemed

inadequate, however, because it does not take into

account the potential donor pool that is dependent

on the rates and causes of death. Medical records

review appears to be the most accurate method

to estimate donor potential within a hospital or a

region.3 A true estimate should reflect contemporary

medical practice, donor identification, and consent

rates; thus it can provide a useful tool for measuring

organ procurement performance in a service area

and highlight areas in the procurement system that

can be improved.

Similar to other parts of the world, the shortage

of organs for transplantation remains a challenge

in Hong Kong. Organ transplants in Hong Kong,

whether cadaver or living donations, are subject

to regulation under the Human Organ Transplant

Ordinance; the main purpose of which is to ensure

that no commercial dealing is involved in organs for

transplant. Currently over 90% of organ donations in

Hong Kong are deceased donations, and the organ

procurement system is based on an opt-in policy

(voluntary decision of the patient or their family to

donate organs). No executed prisoners are involved

in the donation process. Although the deceased

organ donation rate increased from 4.3 donors pmp

in 2006 to 6.1 pmp in 2013, Hong Kong continues

to have one of the lowest donation rates among

developed countries.4 Over 2000 patients were

waiting for a solid-organ transplant in 2014 but only

112 deceased organs were utilised.5

In recent years, approximately 40% of deceased

organ donation referrals in our territory came from

intensive care units (ICUs) while the remainder

came from non-ICU areas such as medical and

neurosurgical wards. This is entirely different from

other parts of the world where more than 90% of

organ donation referrals come from the ICU.6 Most

of the current data on organ donation potential were

solely extracted from medical records in the ICU.2 7 8 9

The picture will be more complete, however, if we can

also identify and include those patients who die in

non-ICU wards but have the potential to become an

organ donor if appropriate steps are taken.10 Nearly

all studies on deceased organ donation have been

performed in western countries and data are scarce

for the Chinese population. The rates of donation

will differ from one country to another because of

differences in cultural, social, and historical factors;

the organisational characteristics of the donation

system; and various aspects of the health service.

We conducted a study to evaluate the deceased

organ donation process at our centre using the

critical pathway11 in order to identify to what extent

and why potential brain-dead donors are missed.

The main outcome measures included the potential

organ donor suitability and the various reasons for

non-donation as assessed by our organ donation

coordinator (ODC). Different ways that could help

to improve the organ donation process will also be

discussed.

Methods

This was a retrospective study conducted at Queen

Elizabeth Hospital, the largest regional acute

hospital in Hong Kong with 1833 beds, serving

approximately 7.1% of our 7.2 million population. It

is a tertiary referral centre of the major specialties

including neurology and neurosurgery. In addition,

it is one of the major organ procurement centres in

our territory and contributed approximately 30%

of all deceased organ donors in 2014. All deceased

donors in our centre are brain-dead donors as we do

not have a donation after cardiac death policy.

Hospital medical records of all those who died

at our centre (including both ICU and non-ICU

areas) between 1 January and 31 December 2014

were reviewed by the same ODC. In case of

ambiguous information, the opinion of another

ODC at our centre was sought. Both ODCs had

experience in managing patients with brain injuries

and were knowledgeable about brain death. Clinical

and demographic data including age, gender, cause

of brain injury, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score,

medical co-morbidities, and likelihood of progression

to brain death were extracted from the medical

records. Only those who had been on mechanical

ventilation with documented brain injuries and

aged ≤75 years were included in our analysis. In our

hospital, patients could receive ventilator care (but

no invasive arterial pressure monitoring) in general

wards other than the 29-bed ICU because the

number of critically ill patients requiring intensive

care might exceed the number of beds available in

ICU. Patients could also be too ill and not fulfil the

ICU admission criteria. During ICU consultations,

patients were triaged by ICU specialists with

reference to a prioritisation model.12 Patients

remaining in the general ward would be cared for by

the treating teams.

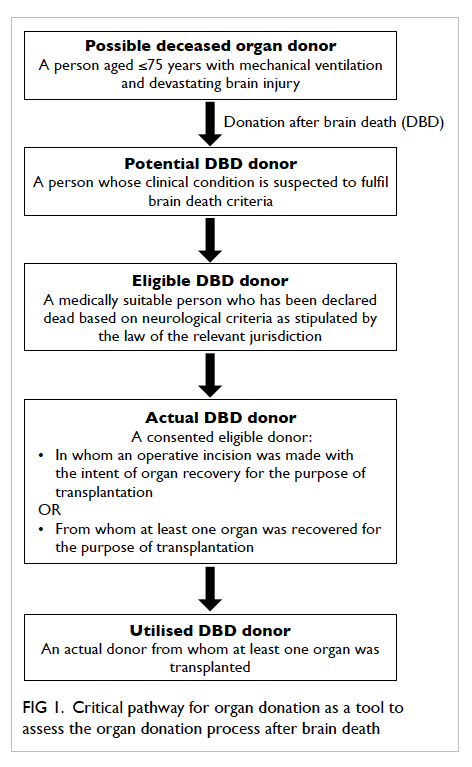

The critical pathway for organ donation was

used as a tool to assess the organ donation process

after brain death.11 The various definitions of organ

donors used in this study are shown in Figure 1. The ‘Guidelines on diagnosis of brain death’ were

first prepared in 1995 with assistance from the

Hong Kong Society of Critical Care Medicine. They

were revised later and supported by the Hospital

Authority (HA) of Hong Kong.13 Brain death is

established by the documentation of irreversible

coma and irreversible loss of brain stem reflex

responses and respiratory centre function or by the

demonstration of the cessation of intracranial blood

flow. The recommendations for the status of the two

medical practitioners certifying death are shown

in the guideline. The concept that brain death is

equivalent to death is accepted legally and within the

medical community in Hong Kong.

Figure 1. Critical pathway for organ donation as a tool to assess the organ donation process after brain death

Medical suitability for organ donation was

based on our ‘Guideline for evaluation and selection

of potential organ/tissue donors’ prepared by the

HA.14 The likelihood of progression to brain death

was based on the GCS score, presence or absence

of brainstem reflexes, rapidity of deterioration, and

findings of cerebral tomography. Potential brain-dead

organ donors were defined as patients with

the likelihood of progression to brain death. The

various reasons why some potential organ donors

did not become an organ donor were recorded and

evaluated. The study was approved by our hospital

ethics committee.

Statistical analyses

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

(Windows version 21.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago [IL],

US) was used to perform the statistical analyses.

Continuous data were expressed as means ± standard

deviations or medians (ranges), and categorical data

were expressed as percentages. Continuous data

were analysed by Mann-Whitney U tests to detect

the difference between groups while categorical data

were analysed by Chi squared test or Fisher’s exact

test. A P value of <0.05 was defined as statistically

significant.

Results

There were a total of 3659 patient deaths during the

study period. Among them, only 233 patients were

put on mechanical ventilation with documented

brain injury. On initial review, 112 patients were

excluded due to old age (>75 years). The remaining

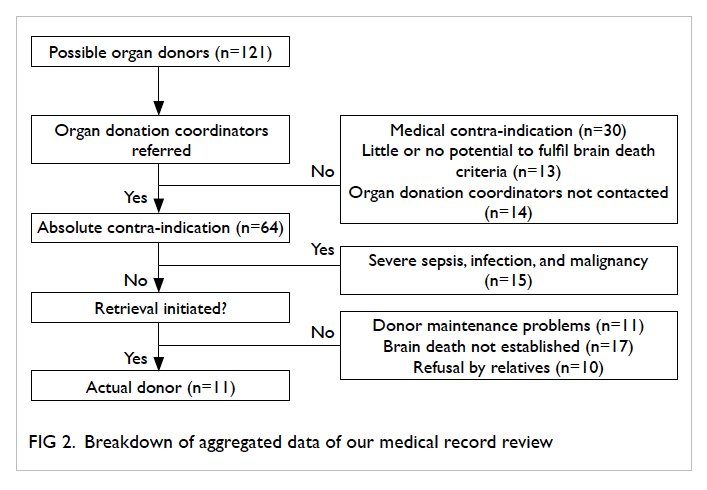

121 possible organ donors were further analysed (Fig 2).

Among the 121 possible organ donors, only 14

(12%) were from ICU. Most were from the non-ICU

areas including 64 from neurosurgical wards and 43

from general medical wards. The mean age of our

possible organ donors was 59.4 ± 13.0 years and 88

were male and 33 female.

Of the 121 possible organ donors, 64 (52.9%)

were identified and referred to ODC for consideration

of organ donation. Only eight (12.5%) patients were

from ICU and 56 (87.5%) were from non-ICU areas.

Among the 64 referred patients, 15 were medically

unsuitable and 11 had maintenance

problems related to haemodynamic instability. For

the remaining 38 patients, brain death diagnosis

could not be established or completed (did not fulfil

all the criteria) in 17. Hence only 21 patients (4 in

ICU and 17 in non-ICU) finally became eligible organ

donors after brain death. The relatives of all these

eligible donors were approached by our ODC, 11 of

them became actual organ donors (3 in ICU and 8 in

non-ICU) and 10 patients did not proceed to organ

donation because of refusal by patient relatives. The

overall consent rate at our centre was 52% and the

consent rate was higher in ICU than in the non-ICU

areas although the difference was not statistically

significant (75% vs 47%; P=0.31). All actual organ

donors finally became utilised organ donors. Of the

57 patients who had not been referred to ODC, 30

were medically unsuitable for organ donation after

careful review of hospital records, 13 had little or

no potential to progress to brain death, while the

remaining 14 could have become potential organ

donors if the ODC had been informed in a timely

manner.

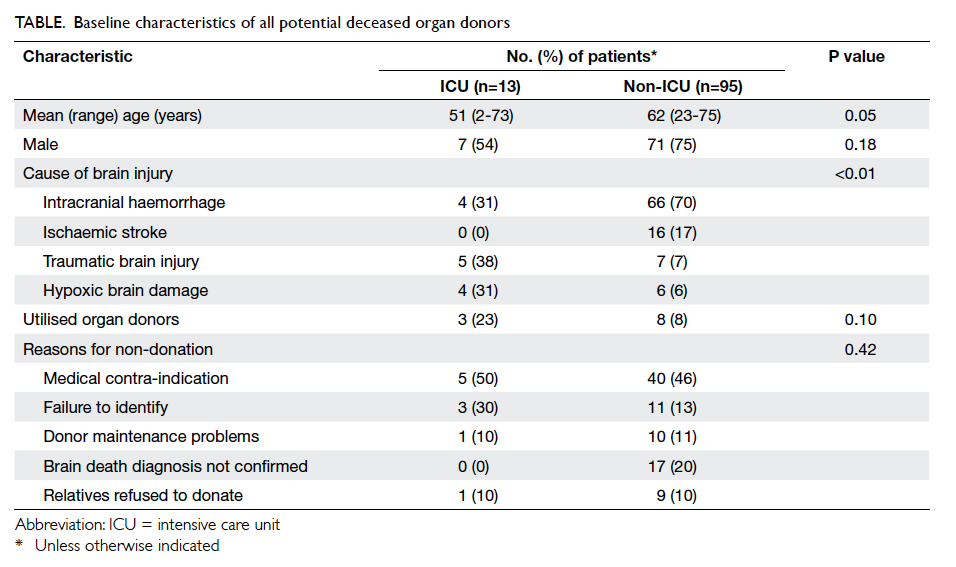

Among the 108 patients who were classified as

potential brain-dead organ donors (after excluding

13 unlikely to fulfil brain death criteria), 13 patients

were from ICU and 95 were from non-ICU areas.

The baseline characteristics of these potential

donors are shown in the Table. The potential donors in ICU were younger than those in non-ICU wards

(although only marginally significant) and there

was no significant difference in gender between

the patients from ICU and non-ICU areas. More

patients had traumatic brain injury and hypoxic

brain damage in ICU and in non-ICU wards

(neurosurgical or medical units) more patients had

intracranial haemorrhage or ischaemic stroke. Only

11 of the 108 patients finally became actual organ

donors with the overall conversion rate of 10%. The

conversion rate was higher in ICU than in non-ICU

although it was not statistically significant (23% vs

8%; P=0.10). The reasons for non-donation (n=97)

included medical contra-indication (n=45, 46%),

failure to identify and inform our ODC (n=14, 14%),

failure of donor maintenance (n=11, 11%), brain

death diagnosis not established or completed (n=17,

18%), and relative’s refusal for organ donation (n=10,

11%). There was no significant difference between

ICU and non-ICU areas concerning the reasons for

non-donation (P=0.42).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive

study to evaluate the pool of potential brain-dead

organ donors in a large regional hospital in the

Chinese community. Lack of consent to a donation

request was the primary cause of the gap between

the number of potential donors and the number

of actual donors in the United States and United

Kingdom.7 8 In order to tackle this problem, more

resources should be invested to improve the process

of obtaining consent.8 Good donor management

including identification, evaluation, and donor

maintenance are also key factors in the successful

recovery of organs in the donation process.

Failure of health care professionals to identify

potential donors is considered an important

contributing factor to the shortage of deceased

organs,11 15 and accounted for 14% of our potential

organ donor loss. Education directed at doctors and

nurses to increase their awareness of possible organ

donors is crucial to the success of an organ donation

programme. Identification of a possible deceased

organ donor should be inherently linked to the act of

referral to a key donation person/team for activation

of the deceased donation process.11 Similar to other

hospitals in Hong Kong, all possible brain-dead

donors at our centre, regardless of apparent medical

contra-indications, are referred to our ODC as

soon as they are identified. Referral usually occurs

early when the clinical condition reveals death to be

imminent or that further treatment will be futile. The

possible deceased organ donors can then be assessed

and managed by the ODC immediately as all the

ODCs in our territory have a centralised shared 24-hour

on-call system. The decision for medical suitability is

made by our ODC and transplant physicians instead

of referring teams because studies have shown that

11% of the decisions not to refer a potential donor

based on medical grounds are incorrect.16 In our

centre, only 52.9% of the possible

deceased organ donors were identified and referred

to our ODC. This figure was lower than some

European countries (approximately 80% on average)

such as 93.6% in France to 47.7% in Finland.9 One

important unique feature in our study was that most

of the potential deceased organ donors at our centre

(also in Hong Kong) were identified in the non-ICU

wards. This was in contrast to other countries where

nearly all potential donors come from ICU.2 9 As a

result, increased awareness of frontline staff and

compulsory referral of all possible deceased organ

donors may further increase the donation rate.

In our study, one third (27/87) of the non-utilised

potential organ donors in the non-ICU areas were

lost either because of a haemodynamically unstable

condition leading to cardiac death or the failure to

confirm or complete the brain death diagnosis. Brain

death is often associated with marked physiological

instability that makes it difficult to be managed in

general wards by non-ICU specialists. In addition,

due to the limited manpower and high hospital

bed occupancy rates, most potential organ donors

in general wards would no longer be supported for

organ donation if brain death could not be confirmed

within 72 hours. These patients might turn out to be

eligible organ donors if they can continue to receive

critical care management in ICU. Our study also showed that the consent rate was higher

for potential donors from ICU than from non-ICU

areas although it was not statistically significant.

Some ICU specialists believe that all potential donors

should be referred to ICU for possible admission

and physiological support through to brain death.10

Additional resources, including ICU specialists

and ICU beds, will be required however. As an

alternative, a mobile team including ICU doctors

and nurses could be set up, aiming to give advice for

potential organ donor support and optimisation of

settings towards brainstem tests in non-ICU wards.

As in many other countries, a high family

refusal rate is a significant reason for potential

donor losses in Hong Kong. In our study, the overall

refusal rate was 48%. This was higher than the family

refusal rates in Spain (24.3%), the United Kingdom

(41%), France and Belgium (10.5% in both).7 9 There

are numerous ethnic, cultural, social, and religious

factors that contribute to disparities in deceased

donation in different Asian countries. Since the

Chinese community is deeply embedded with the

traditional belief of preserving body integrity after

death, most Chinese communities such as Hong

Kong have adopted an opt-in system.16 The presumed

consent or opt-out system is a controversial topic in

our territory. It is uncertain whether the public would

support presumed consent17 because it violates our

conventional ethical and legal principle of familial

authority over a deceased body. A survey in Hong

Kong showed clear objection (66%) to presumed

consent for organ donation and only 28% agreed.18

Any health policies and educational campaigns to

increase donation rates must contend with different

cultural contexts and conceptions of autonomy to

be effective. In November 2008, the Hong Kong

SAR Government established the Centralised Organ

Donation Register to make it more convenient

for people to register their wish to donate organs

after death. Media coverage of patients’ appeals

for organs and transplant success stories can draw

public support and boost public confidence in organ

transplantation.19

One of the drawbacks of our study was the

small number of patients that might not provide

sufficient power to detect the differences between

potential donors from ICU and non-ICU areas. It

is also difficult to compare our results exactly with

other studies because of the variation in definition

of a potential donor and the difficulty in predicting

the likelihood of progression to brain death.

Furthermore, as we only analysed those patients

who were mechanically ventilated, some potential

organ donors might still be missed as it is not our

current practice to perform tracheal intubation and

mechanical ventilation solely for the purposes of

facilitating organ donation.

Conclusions

We have identified different areas in the donation

process where it may be possible to increase the organ

donation rate considerably. Among them, increasing

awareness of frontline staff in identification of

potential donors in both ICU and non-ICU areas,

and appropriate physiological support of potential

donors to accomplish the diagnosis of brain death

in general wards are key elements in our hospital.

Ongoing accurate audit of practice is a prerequisite

to improve the organ donation process.

Declaration

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

References

1. OPTN (Organ Procurement and Transplantation

Network). U. S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Available from: http://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov. Accessed 1

Jun 2015.

2. Jansen NE, van Leiden HA, Haase-Kromwijk BJ, Hoitsma

AJ. Organ donation performance in the Netherlands 2005-08; medical record review in 64 hospitals. Nephrol Dial

Transplant 2010;25:1992-7. Crossref

3. Christiansen CL, Gortmaker SL, Williams JM, et al. A

method for estimating solid organ donor potential by organ

procurement region. Am J Public Health 1998;88:1645-50. Crossref

4. IRODaT (International Registry in Organ Donation and

Transplantation). Transplant Procurement Management.

Available from: http://www.irodat.org. Accessed 1 Jun

2015.

5. Department of Health, The Hong Kong SAR Government.

Organ donation. Available from: http://www.organdonation.gov.hk/eng/statistics.html. Accessed 1 Jun

2015.

6. Mascia L, Mastromauro I, Viberti S, Vincenzi M, Zanello

M. Management to optimize organ procurement in brain

dead donors. Minerva Anestesiol 2009;75:125-33.

7. Barber K, Falvey S, Hamilton C, Collett D, Rudge C.

Potential for organ donation in the United Kingdom: audit

of intensive care records. BMJ 2006;332:1124-7. Crossref

8. Sheehy E, Conrad SL, Brigham LE, et al. Estimating the

number of potential organ donors in the United States. N

Engl J Med 2003;349:667-74. Crossref

9. Roels L, Spaight C, Smits J, Cohen B. Donation patterns

in four European countries: data from the donor action

database. Transplantation 2008;86:1738-43. Crossref

10. Opdam HI, Silvester W. Identifying the potential organ

donor: an audit of hospital deaths. Intensive Care Med

2004;30:1390-7. Crossref

11. Domínguez-Gil B, Delmonico FL, Shaheen FA, et al.

The critical pathway for deceased donation: reportable

uniformity in the approach to deceased donation. Transpl

Int 2011;24:373-8. Crossref

12. Guidelines for intensive care unit admission, discharge,

and triage. Task Force of the American College of Critical

Care Medicine, Society of Critical Care Medicine. Crit

Care Med 1999;27:633-8. Crossref

13. Hospital Authority Head Office Operations Circular No. 13 / 2010: Guidelines on diagnosis of brain death. Hong Kong: Hospital Authority; 2010.

14. Guideline for evaluation and selection of potential organ/tissue donors (revised version). Hong Kong: Hospital Authority; 2016.

15. Boey KW. A cross-validation study of nurses’ attitudes and

commitment to organ donation in Hong Kong. Int J Nur

Stud 2002;39:95-104. Crossref

16. Wu AM. Discussion of posthumous organ donation in

Chinese families. Psychol Health Med 2008;13:48-54. Crossref

17. Wu AM, Tang CS. The negative impact of death anxiety

on self-efficacy and willingness to donate organs among

Chinese adults. Death Stud 2009;33:51-72. Crossref

18. Cheng B, Ho CP, Ho S, Wong A. An overview on attitudes

towards organ donation in Hong Kong. Hong Kong J

Nephrol 2005;2:77-81. Crossref

19. Lo CM. Deceased donation in Asia: challenges and

opportunities. Liver Transpl 2012;18 Suppl 2:S5-7. Crossref