Hong Kong Med J 2016 Dec;22(6):538–45 | Epub 24 Oct 2016

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj154799

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Effectiveness of proximal intra-operative salvage Palmaz stent placement for endoleak during endovascular aneurysm repair

Y Law, MB, BS, FRCS (Edin);

YC Chan, MB, BS, FRCS (Eng);

Stephen WK Cheng, MB, BS, FRCS (Edin)

Division of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery, Department of Surgery, The University of Hong Kong, Queen Mary Hospital, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

This paper was presented in abstract form at the 15th Congress of Asian

Society for Vascular Surgery (ASVS) Hong Kong, 5-7 September 2014,

Hong Kong.

Corresponding author: Dr Y Law (lawyuksimpson@gmail.com)

Abstract

Introduction: The use of a proximal Palmaz stent

is a well-recognised technique to treat proximal

endoleak in endovascular aortic repair. This study

aimed to report the effectiveness and safety of an

intra-operative Palmaz stent for immediate type 1a

endoleak in Hong Kong patients.

Methods: This case series was conducted at a

tertiary hospital in Hong Kong. In a cohort of 494

patients who underwent infrarenal endovascular

aortic repair from July 1999 to September 2015,

12 (2.4%) received an intra-operative proximal

Palmaz stent for type 1a endoleak. Immediate and

subsequent proximal endoleak on follow-up image

was documented.

Results: Morphological review of the pre-repair

aneurysm neck showed five conical, one funnel, five

cylindrical and one undetermined short neck, with

a median neck angle of 61 degrees (range, 19-109

degrees). Stent grafts used included seven Cook

Zenith, one Cook Aorto-Uni-Iliac device, three

Metronic Endurant, and one TriVascular Ovation.

Eleven Palmaz stents were placed successfully

as intended, but one of them was accidentally

placed too low. Of the 12 type 1a endoleaks, postoperative imaging revealed immediate resolution of eight whilst four had improved. After a median follow-up

of 16 (range, 1-59) months, none of the subsequent

imaging showed a type 1a endoleak. The mean size

of the aneurysm sac reduced from 7.4 cm preoperatively to 7.3 cm at 1 month, 6.9 cm at 6 months, 7.1 cm at 1 year, and 6.1 cm at 2 years postoperatively. None of these patients required aortic

reintervention or had device-related early- or mid-term

mortality. One patient required delayed iliac

re-interventions for an occluded limb at 10 days post-surgery.

Conclusion: In our cohort, Palmaz stenting was

effective and safe in securing proximal sealing and

fixation.

New knowledge added by this study

- Palmaz stenting is effective and safe as a salvage treatment of proximal endoleak during endovascular aortic repair (EVAR).

- Appropriate patient selection, meticulous preoperative planning, and diligent follow-up ensured the ultimate success of EVAR.

- A Palmaz stent should always be readily available during EVAR especially for aneurysms with a hostile aortic neck.

Introduction

Hostile proximal infrarenal aortic neck is often

considered one of the relative contra-indications

for infrarenal endovascular aortic repair (EVAR),

but large multicentre registries have shown that

more EVARs have been performed worldwide

beyond manufacturers’ indications.1 2 3 Data from

the EUROSTAR Registry more than a decade ago

looking at aneurysm morphology and procedural

details of 2272 patients showed that perioperative

type 1a endoleak was significantly associated with

a larger angulated infrarenal neck with thrombus.4

Other morphological features included short aortic

neck length, large sac diameter, severe angulation,

and conical neck configuration.5 Endoleak is defined

as the persistence of blood flow outside the lumen of

an endovascular graft but within an aneurysm sac.

Type 1a endoleak is a leak around the proximal graft

attachment site. They are clinically important since

they can lead to continual aneurysm enlargement

and eventual rupture.6

Although the development of renal and

mesenteric fenestration or branched stent graft

technology to extend the landing zone more

proximally may overcome type 1a endoleaks, these

devices may not be ideal because of regulations,

complexity, and manufacturing delays.7 In addition,

contemporary published literature does not provide

sufficiently strong evidence to warrant a change in

treatment guidelines for juxtarenal or short-neck

aneurysm.8

The use of a proximal giant Palmaz stent

(Cordis Corp, Fremont [CA], US) is a well-recognised

technique to manage a type 1a endoleak

intra-operatively.9 10 11 12 A prophylactic Palmaz stent

inserted for hostile neck has also been reported.13 14 15

The aim of this study was to report the effectiveness

and safety of an intra-operative Palmaz stent for an

immediate type 1a endoleak.

Methods

Patient selection

Patients with an infrarenal abdominal aortic

aneurysm (AAA) who had undergone EVAR were

retrospectively reviewed for the period 1 July 1999

to 30 September 2015. Data were extracted from

prospectively collected computerised departmental

database, supplemented by patient records. This study was done in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients had undergone a preoperative fine-cut

computed tomographic (CT) scan and careful

preoperative planning with a conclusion that EVAR

was feasible. All our patients who underwent EVAR

had preoperative three-dimensional aortic

anatomy examined using the stationary TeraRecon

Aquarius workstation (TeraRecon, San Mateo [CA],

US) that rapidly manipulates all preoperative data

sets in the Digital Imaging and Communications

in Medicine, and examines the aortic morphology.

These details would be difficult to appreciate on

two-dimensional planar CT imaging, especially in those with

inadequate short hostile neck. Those patients who

were deemed unsuitable for infrarenal sealing

would either undergo open repair or, more recently,

fenestrated or adjunctive EVAR (such as chimney

technique).

Cook Zenith (Cook Medical, Bloomington

[IN], US), Medtronic Endurant (Medtronic Inc,

Minneapolis [MN], US), and TriVascular Ovation

(TriVascular Inc, Santa Rosa [CA], US) stent

grafts were most commonly used. We sometimes

extended the manufacturers’ indications of use to

include difficult aortic necks. All operations were

performed in our institution, a tertiary vascular

referral centre, by experienced vascular specialists

in a hybrid endovascular suite (Siemens Artis zee

Multipurpose System; Siemens, Erlangen, Germany).

Post-deployment balloon moldings with Coda

balloon (Cook Medical, Bloomington [IN], US) and

completion angiograms with power injection were

performed in all patients.

Proximal Palmaz stent placement

In the event of proximal endoleak on completion

angiogram, further balloon molding would be

attempted. Persistent endoleak was managed with

balloon expandable giant Palmaz stent P4014 (Cordis

Corp). Our preference was for the Palmaz stent

to be positioned at the infrarenal region over the

fabric of the stent graft, so as not to jeopardise any

future chance of proximal extension with a renal or

mesenteric fenestrated cuff. They would be crimped

on a Coda balloon (maximum inflated diameter, 40

mm) and railed through a stiff guidewire to the top

neck.

Preoperative aneurysm neck morphological analysis

Cause of proximal endoleak was usually hostile neck.

We focused on aortic infrarenal neck anatomy where

the Palmaz stent was placed and exerted its effect. All

preoperative CT scans were analysed. Measurement

was automatically calculated by computer software

Aquarius iNtuition Client version 4.4 (TeraRecon

Inc), after a median centre line path (MCLP) was

drawn. We used definitions of neck measurement as

defined by Filis et al16:

(1) Neck length is calculated between the point of

MCLP at the orifice of the lower renal artery

and MCLP at the start of the aneurysm.

(2) Neck diameter is measured on the orthogonal

cross-section of the neck, from the outer wall to

the outer wall. It is measured at the lower renal

artery level, 1 cm and 2 cm below.

(3) Neck angle is the angle between the axis of the

neck (straight line between the MCLP of the

aorta at the level of the orifice of the lower renal

artery and the MCLP of the aorta at the start of

the aneurysm) and the axis of the lumen of the

aneurysm (straight line between the MCLP at

the start of the aneurysm and the MCLP at the

end of the aneurysm).

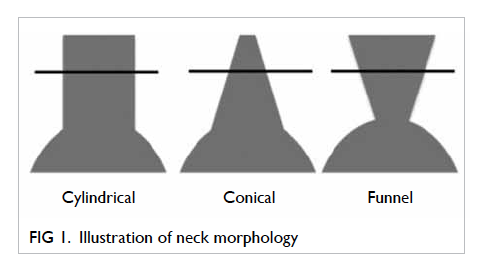

(4) Neck morphology (Fig 1):

(a) Funnel shape is defined as 20% decrease in neck area between the level of the lower renal artery and 2 cm below.

(b) Conical shape is defined as 20% increase in neck area between the level of the renal artery and 2 cm below.

(c) Cylindrical shape is defined between the above two.

(d) Shape is undetermined if neck length is less than 2 cm.

(a) Funnel shape is defined as 20% decrease in neck area between the level of the lower renal artery and 2 cm below.

(b) Conical shape is defined as 20% increase in neck area between the level of the renal artery and 2 cm below.

(c) Cylindrical shape is defined between the above two.

(d) Shape is undetermined if neck length is less than 2 cm.

Clinical and radiological outcomes

Immediate radiological result following Palmaz stent

placement was reported. Any procedural mortality

or morbidity was recorded. Our departmental

protocol recommends postoperative imaging, either

CT scan or duplex scan, at 1 to 3 months, then

every 6 months for the first 2 years, and annually

thereafter. These were supplemented by X-ray to

detect any stent fracture or migration. Any endoleak

detected during follow-up was reported as well as

any alteration in sac size. Follow-up was dated to the

most recent objective imaging available.

Results

Patient population

During the study period 1 July 1999 to 30 September

2015, a total of 842 AAA surgeries were performed,

of which 320 (38%) were open repair and 522 (62%)

were endovascular repair (28 fenestrated/branched

EVAR and 494 infrarenal EVAR). In a cohort of 494

patients with infrarenal EVAR, 12 (2.4%) received

an intra-operative proximal Palmaz stent for type 1a

endoleak that was noticed on completion angiogram.

No patients received prophylactic Palmaz stent for

difficult neck anatomy.

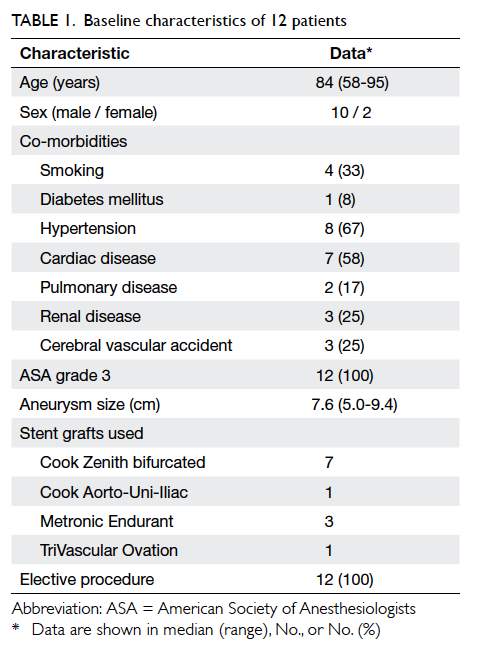

Patient demographics are summarised in Table 1. The median age was 84 (range, 58-95) years. All had undergone elective surgery for asymptomatic

AAA. The median AAA size was 7.6 cm (range,

5.0-9.4 cm). Seven patients received a Cook Zenith

stent graft, one patient a Cook Aorto-Uni-Iliac

device, three had Metronic Endurant stent grafts,

and one had TriVascular Ovation stent graft. The

occurrence of type 1a endoleak was more common in recent years (Table 2).

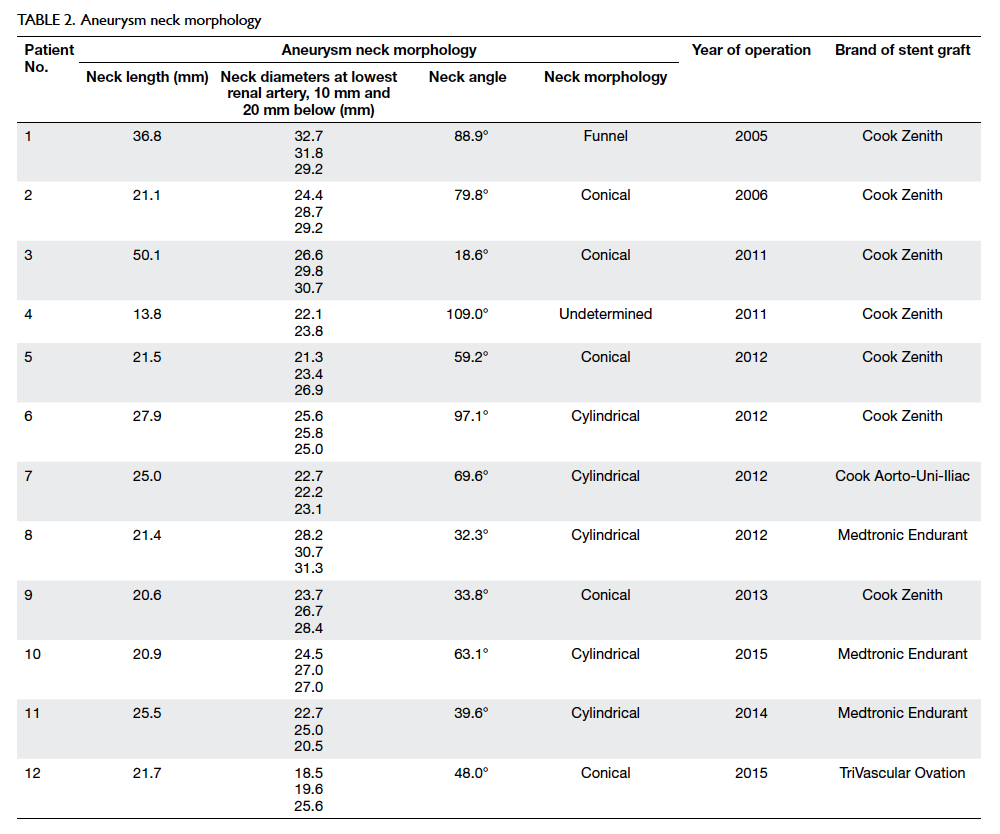

Analysis of aneurysm neck morphology

Table 2 summarises the neck morphologies of our

cohort. Morphological review of the pre-EVAR

aneurysm neck showed five conical, one funnel, five

cylindrical, and one undetermined short necks. The

median neck angle was 61 degrees (range, 19-109

degrees). Use of the stent graft was outside of the

manufacturer’s guidelines in six (50%) patients. Most

patients had one or more features of hostile neck,

rendering them at high risk of proximal endoleak.

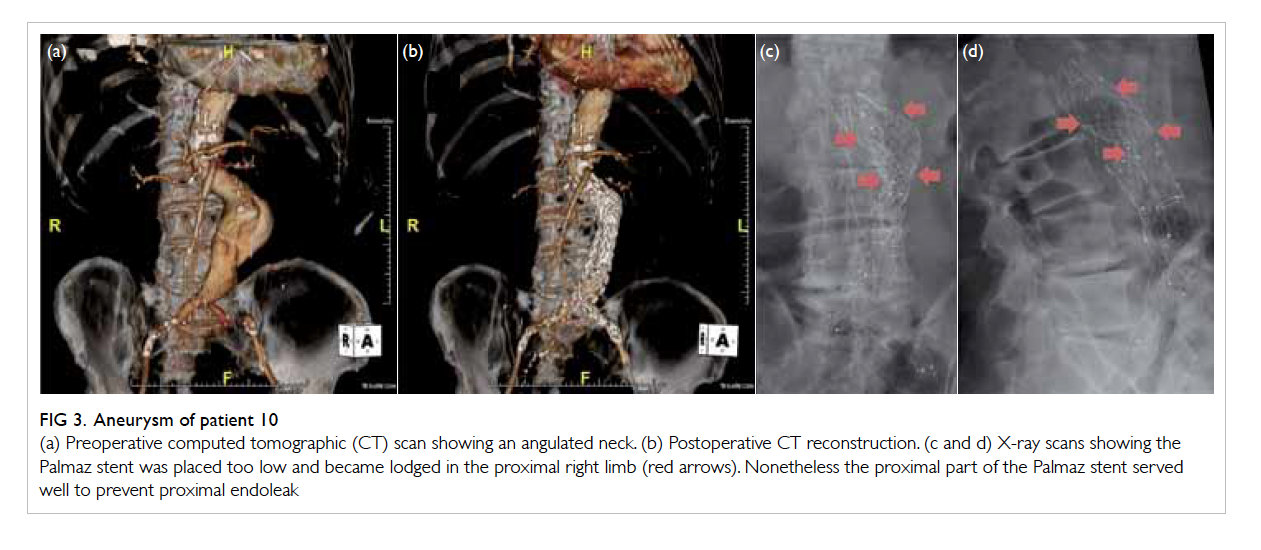

Radiological outcomes

All 12 patients had persistent proximal type 1a

endoleak after stent graft placement with standard

balloon molding. Placement of a giant Palmaz stent

in the infrarenal position was technically successful

in all cases, although one Palmaz stent was placed

too low and lodged in one of the iliac limbs.

Nonetheless, it served its function well in correcting

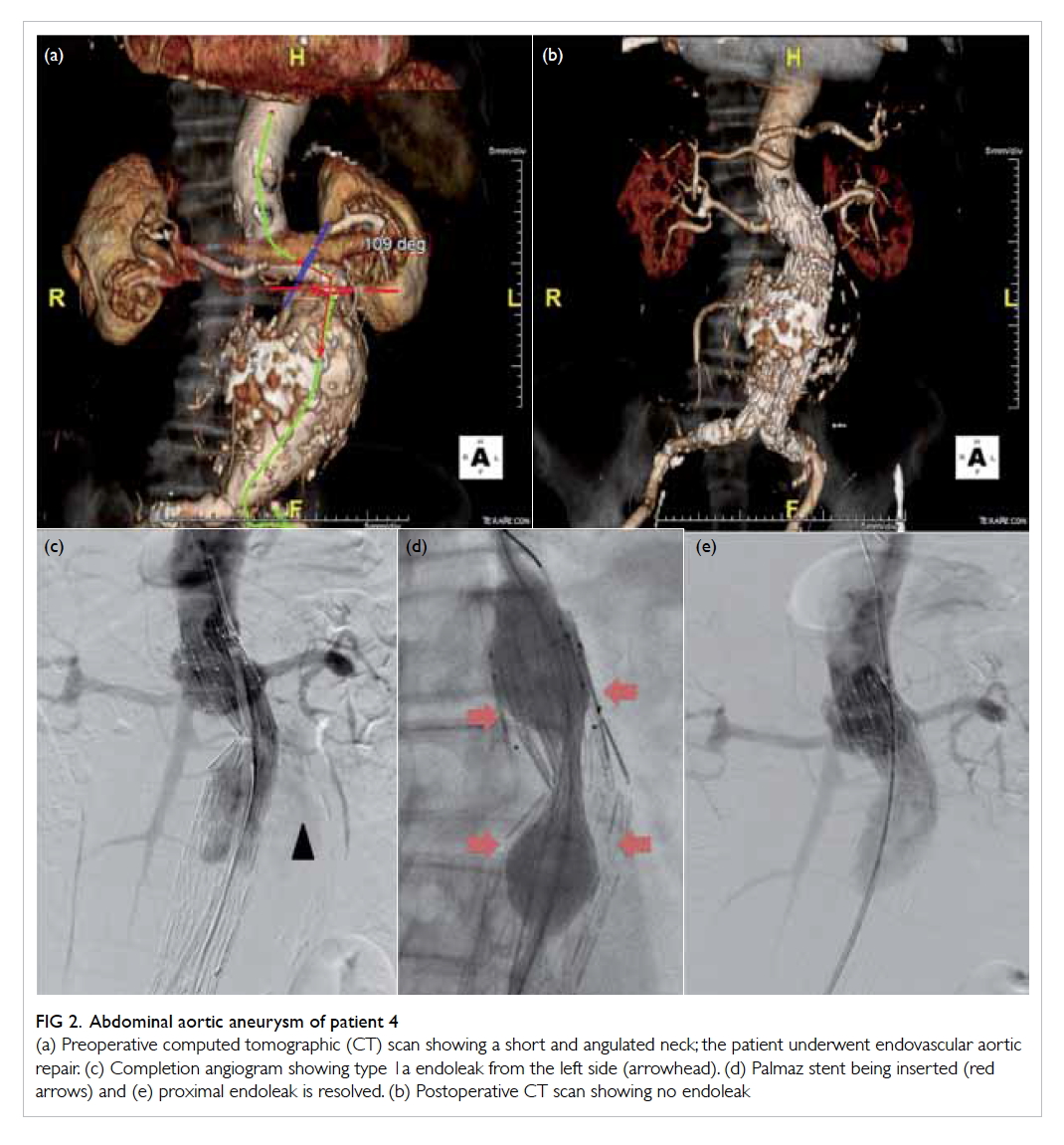

the proximal endoleak (Figs 2 and 3). Immediate

resolution of the endoleak was achieved in eight

(67%); whilst four (33%) had improved but persistent

leak at completion of the procedure.

Figure 2. Abdominal aortic aneurysm of patient 4

(a) Preoperative computed tomographic (CT) scan showing a short and angulated neck; the patient underwent endovascular aortic repair. (c) Completion angiogram showing type 1a endoleak from the left side (arrowhead). (d) Palmaz stent being inserted (red arrows) and (e) proximal endoleak is resolved. (b) Postoperative CT scan showing no endoleak

Figure 3. Aneurysm of patient 10

(a) Preoperative computed tomographic (CT) scan showing an angulated neck. (b) Postoperative CT reconstruction. (c and d) X-ray scans showing the Palmaz stent was placed too low and became lodged in the proximal right limb (red arrows). Nonetheless the proximal part of the Palmaz stent served well to prevent proximal endoleak

Clinical outcomes

After a median follow-up of 16 (range, 1-59) months,

no patient had a type 1a endoleak on subsequent

imaging, either CT scan or duplex ultrasound scan.

All patients had at least one postoperative CT scan.

Patient 2 had a type 1c endoleak from an

embolised left internal iliac artery that was managed

conservatively. Patients 9 and 11 had a

type 2 endoleak, also managed conservatively. All

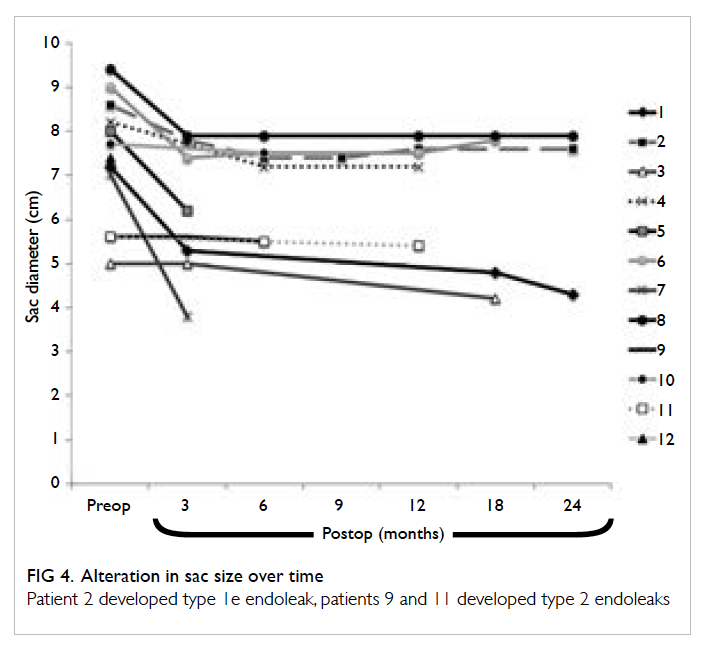

had shrinkage of sac size. Sac size of the aneurysms

decreased from a mean of 7.4 cm pre-EVAR to 7.3

cm, 6.9 cm, 7.1 cm, and 6.1 cm at 1 month, 6 months,

1 year, and 2 years post-EVAR, respectively (Fig 4).

Routine X-ray surveillance did not reveal any Palmaz

stent fracture or migration.

Figure 4. Alteration in sac size over time

Patient 2 developed type 1e endoleak, patients 9 and 11 developed type 2 endoleaks

One patient required secondary endovascular

re-intervention for occluded left iliac limb at day 10

postoperatively. It was due to a tortuous iliac system

causing an acute bend to the stent graft limb. There

was no other reported secondary intervention. Seven

patients have since died (at 6, 9, 16, 16, 20, 24, and 59

postoperative months) from non-aneurysm–related

causes. Five remain alive at the time of writing.

Discussion

Hostile aortic neck anatomy often precludes

endovascular treatment of AAA. It has been shown

in large clinical cohorts that up to 42% of EVARs

are performed outside the instructions for use for

commercially available stent grafts.3 17 18 19 Multiple

measures have been developed to include more of

these difficult necks for endovascular treatment.

Evolution of stent graft design including suprarenal

fixation20 and renal and mesenteric fenestration21 are examples. Adjunctive neck measures, eg

endostapling,22 23 proximal fibrin glue embolisation,24

open aortic neck banding,25 and proximal covered cuff

extension10 may be used in cases of perioperative

type 1a endoleak following EVAR. Endostapling and

glue embolisation, though minimally invasive, are

not always feasible and risk major aortic injury. Open

aortic neck banding requires laparotomy. Proximal

cuff extension is only feasible if there is an additional

sealing zone to the most caudal renal artery. Since

we routinely landed our stent graft at the level of the

lowest renal artery, this technique was not usually

practical. The simplest and most well-recognised

manoeuvre remains placement of a proximal Palmaz

stent.

The morphology of the infrarenal aortic neck

is important in securing the proximal landing zone.

Three-dimensional workstation planning has been considered

useful by many26 27; for example, Sobocinski et al28

showed that it reduced the rate of type 1 endoleaks

and Velazquez et al29 indicated that it decreased

the rate of extra iliac extension. We emphasise the

importance of proper pre-EVAR planning, as this

is one of the obvious factors that may compromise

long-term durability and outcome. The fact that half

of stent graft usage in our series was outside the

instructions for use and most patients had one or

more hostile neck feature rendered them at high risk

of proximal endoleak. Under these circumstances,

a Palmaz stent should always be readily available

during EVAR.

Multiple series have reported their experience

in its successful use. Early study by Dias et al9

reported nine patients who received a Palmaz

stent and in whom aneurysm remained excluded

at a median follow-up of 13 months (range, 6-24

months). Rajani et al10 reported successful treatment

of intra-operative type 1 endoleak with Palmaz stent

in 27 patients who had no recurrence at follow-up,

although length of follow-up was not mentioned.

Arthurs et al11 reported no type 1 endoleak in 31

patients after a median follow-up of 53 months

(interquartile range, 14-91 months). The Palmaz

stent was effective across a variety of available

devices with suprarenal fixation (eg Cook Zenith)

or infrarenal fixation (eg Gore Excluder; WL Gore

& Associates, Inc, Newark [DE], US). Our results are

in agreement with these findings.

Other series have shown controversial

results. Farley et al15 reported 18 cases of Palmaz

stent placement. Technical placement failed in one

patient, in whom attempts at passing the access

sheath to the proximal landing zone resulted in

proximal migration of the main body of the aortic

stent graft. An attempt at passage of the balloon-mounted

stent without sheath protection resulted

in slippage of the stent from the balloon. The stent

could not be retrieved and was deployed in the iliac

limb. With a mean follow-up period of 254 days

in the 17 successful Palmaz stent placements, one

patient had unresolved type 1 endoleak. Malposition

of the stent was not an unusual complication.30 31 Kim et al32 described a deployment technique to ensure

accuracy. Palmaz stent was asymmetrically hand-crimped

on an appropriately sized valvuloplasty

balloon that assured the proximal aspect would

deploy first.

Some series have advocated prophylactic

Palmaz stent placement in hostile necks, including

15 patients reported by Cox et al.13 One (7%) patient

had secondary endoleak with intervention after

a mean follow-up of 12 months. Qu and Raithel14

reported 117 cases of difficult neck treated with

unibody Powerlink device (Endologix Inc, Irvine

[CA], US). In this series, 83 (72.8%) had proximal

Palmaz stent as an adjunctive procedure. Proximal

cuff extension was also used. The mean follow-up

was 2.6 years (range, 4 months-5 years). Results were

satisfactory with an overall re-intervention rate of

5.3%, and no device migration, conversion, or post-EVAR rupture.

Palmaz stents were routinely placed at an

infrarenal position in our unit on the basis that

future extension with a fenestrated cuff is possible.

If a transrenal position is adopted, the strut of the

Palmaz stent, which is a very tight space, may hinder

catheterisation of renal or visceral arteries should

a fenestrated cuff be inserted. This is not absolute,

however. Oikonomou et al33 reported a case of post-treatment

with Powerlink stent graft and transrenal

Palmaz stent. Treatment of proximal endoleak at 3

years after operation was successful by means of a

proximal fenestrated graft. Selective catheterisation

of both renal arteries and dilation of the stent struts

prior to stent graft repair ensured that it would be

feasible to catheterise the renal arteries through the

fenestrated cuff.

There are limitations to this study. The

retrospective nature of our cohort may risk inaccurate

information. The efficacy of the Palmaz stent in

aneurysms with short infrarenal neck may not be

tested, as the majority were considered straight for

custom-made fenestrated or branched EVAR. In our

limited experience, a Palmaz stent is a valuable tool

to expand the boundary of endovascular treatment

for AAA.

Conclusion

Palmaz stent helps proximal sealing and fixation.

In our experience, Palmaz stenting is effective

and safe as a salvage treatment of immediate

proximal endoleak during EVAR. We emphasise the

importance of appropriate patient selection, pre-EVAR planning, and diligent follow-up.

Declaration

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Bachoo P, Verhoeven EL, Larzon T. Early outcome of

endovascular aneurysm repair in challenging aortic neck

morphology based on experience from the GREAT C3

registry. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 2013;54:573-80.

2. Matsumoto T, Tanaka S, Okadome J, et al. Midterm

outcomes of endovascular repair for abdominal aortic

aneurysms with the on-label use compared with the off-label

use of an endoprosthesis. Surg Today 2015;45:880-5. Crossref

3. Hoshina K, Hashimoto T, Kato M, Ohkubo N, Shigematsu

K, Miyata T. Feasibility of endovascular abdominal aortic

aneurysm repair outside of the instructions for use and

morphological changes at 3 years after the procedure. Ann

Vasc Dis 2014;7:34-9. Crossref

4. Buth J, Harris PL, van Marrewijk C, Fransen G. The

significance and management of different types of

endoleaks. Semin Vasc Surg 2003;16:95-102. Crossref

5. Stanley BM, Semmens JB, Mai Q, et al. Evaluation of

patient selection guidelines for endoluminal AAA repair

with the Zenith Stent-Graft: the Australasian experience.

J Endovasc Ther 2001;8:457-64. Crossref

6. Fransen GA, Vallabhaneni SR Sr, van Marrewijk CJ, et al.

Rupture of infra-renal aortic aneurysm after endovascular

repair: a series from EUROSTAR registry. Eur J Vasc

Endovasc Surg 2003;26:487-93. Crossref

7. Chuter T, Greenberg RK. Standardized off-the-shelf

components for multibranched endovascular repair of

thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysms. Perspect Vasc Surg

Endovasc Ther 2011;23:195-201. Crossref

8. Ou J, Chan YC, Cheng SW. A systematic review of

fenestrated endovascular repair for juxtarenal and short-neck

aortic aneurysm: evidence so far. Ann Vasc Surg

2015;29:1680-8. Crossref

9. Dias NV, Resch T, Malina M, Lindblad B, Ivancev K.

Intraoperative proximal endoleaks during AAA stent-graft

repair: evaluation of risk factors and treatment with

Palmaz stents. J Endovasc Ther 2001;8:268-73. Crossref

10. Rajani RR, Arthurs ZM, Srivastava SD, Lyden SP, Clair DG,

Eagleton MJ. Repairing immediate proximal endoleaks

during abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg

2011;53:1174-7. Crossref

11. Arthurs ZM, Lyden SP, Rajani RR, Eagleton MJ, Clair

DG. Long-term outcomes of Palmaz stent placement

for intraoperative type Ia endoleak during endovascular

aneurysm repair. Ann Vasc Surg 2011;25:120-6. Crossref

12. Chung J, Corriere MA, Milner R, et al. Midterm results

of adjunctive neck therapies performed during elective

infrarenal aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg 2010;52:1435-41. Crossref

13. Cox DE, Jacobs DL, Motaganahalli RL, Wittgen CM,

Peterson GJ. Outcomes of endovascular AAA repair

in patients with hostile neck anatomy using adjunctive

balloon-expandable stents. Vasc Endovascular Surg

2006;40:35-40. Crossref

14. Qu L, Raithel D. Experience with the Endologix Powerlink

endograft in endovascular repair of abdominal aortic

aneurysms with short and angulated necks. Perspect Vasc

Surg Endovasc Ther 2008;20:158-66. Crossref

15. Farley SM, Rigberg D, Jimenez JC, Moore W, Quinones-Baldrich W. A retrospective review of Palmaz stenting of

the aortic neck for endovascular aneurysm repair. Ann

Vasc Surg 2011;25:735-9. Crossref

16. Filis KA, Arko FR, Rubin GD, Zarins CK. Three-dimensional

CT evaluation for endovascular abdominal

aortic aneurysm repair. Quantitative assessment of the

infrarenal aortic neck. Acta Chir Belg 2003;103:81-6. Crossref

17. Walker J, Tucker LY, Goodney P, et al. Adherence to

endovascular aortic aneurysm repair device instructions

for use guidelines has no impact on outcomes. J Vasc Surg

2015;61:1151-9. Crossref

18. Igari K, Kudo T, Toyofuku T, Jibiki M, Inoue Y. Outcomes

following endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair

both within and outside of the instructions for use. Ann

Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014;20:61-6. Crossref

19. Lee JT, Ullery BW, Zarins CK, Olcott C 4th, Harris

EJ Jr, Dalman RL. EVAR deployment in anatomically

challenging necks outside the IFU. Eur J Vasc Endovasc

Surg 2013;46:65-73. Crossref

20. Robbins M, Kritpracha B, Beebe HG, Criado FJ, Daoud Y,

Comerota AJ. Suprarenal endograft fixation avoids adverse

outcomes associated with aortic neck angulation. Ann

Vasc Surg 2005;19:172-7. Crossref

21. Verhoeven EL, Vourliotakis G, Bos WT, et al. Fenestrated

stent grafting for short-necked and juxtarenal abdominal

aortic aneurysm: an 8-year single-centre experience. Eur J

Vasc Endovasc Surg 2010;39:529-36. Crossref

22. Donas KP, Kafetzakis A, Umscheid T, Tessarek J, Torsello

G. Vascular endostapling: new concept for endovascular

fixation of aortic stent-grafts. J Endovasc Ther 2008;15:499-503. Crossref

23. Avci M, Vos JA, Kolvenbach RR, et al. The use of

endoanchors in repair EVAR cases to improve proximal

endograft fixation. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 2012;53:419-26.

24. Feng JX, Lu QS, Jing ZP, et al. Fibrin glue embolization

treating intra-operative type I endoleak of endovascular

repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm: long-term result [in

Chinese]. Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi 2011;49:883-7.

25. Scarcello E, Serra R, Morrone F, Tarsitano S, Triggiani

G, de Franciscis S. Aortic banding and endovascular

aneurysm repair in a case of juxtarenal aortic aneurysm

with unsuitable infrarenal neck. J Vasc Surg 2012;56:208-11. Crossref

26. Lee WA. Endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm

sizing and case planning using the TeraRecon Aquarius

workstation. Vasc Endovascular Surg 2007;41:61-7. Crossref

27. Parker MV, O’Donnell SD, Chang AS, et al. What imaging

studies are necessary for abdominal aortic endograft sizing?

A prospective blinded study using conventional computed

tomography, aortography, and three-dimensional

computed tomography. J Vasc Surg 2005;41:199-205. Crossref

28. Sobocinski J, Chenorhokian H, Maurel B, et al. The benefits

of EVAR planning using a 3D workstation. Eur J Vasc

Endovasc Surg 2013;46:418-23. Crossref

29. Velazquez OC, Woo EY, Carpenter JP, Golden MA, Barker

CF, Fairman RM. Decreased use of iliac extensions and

reduced graft junctions with software-assisted centerline

measurements in selection of endograft components for

endovascular aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg 2004;40:222-7. Crossref

30. Gabelmann A, Krämer SC, Tomczak R, Görich J.

Percutaneous techniques for managing maldeployed or

migrated stents. J Endovasc Ther 2001;8:291-302. Crossref

31. Slonim SM, Dake MD, Razavi MK, et al. Management of

misplaced or migrated endovascular stents. J Vasc Interv

Radiol 1999;10:851-9. Crossref

32. Kim JK, Noll RE Jr, Tonnessen BH, Sternbergh WC 3rd.

A technique for increased accuracy in the placement of

the “giant” Palmaz stent for treatment of type IA endoleak

after endovascular abdominal aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg

2008;48:755-7. Crossref

33. Oikonomou K, Botos B, Bracale UM, Verhoeven EL.

Proximal type I endoleak after previous EVAR with

Palmaz stents crossing the renal arteries: treatment using a

fenestrated cuff. J Endovasc Ther 2012;19:672-6. Crossref