Hong Kong Med J 2016 Dec;22(6):534–7 | Epub 9 Sep 2016

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj154694

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Nephrolithiasis among male patients with newly diagnosed gout

KS Wan, MD, PhD1,2;

CK Liu, MD, MPH3,4;

MC Ko, MD3;

WK Lee, MD3;

CS Huang, MD2

1 Department of Immunology and Rheumatology, Taipei City Hospital-Zhongxing Branch, Taiwan

2 Department of Pediatrics, Taipei City Hospital-Renai Branch, Taiwan

3 Department of Urology, Taipei City Hospital-Zhongxing Branch, Taiwan

4 Fu Jen Catholic University School of Medicine, Taiwan

Corresponding author: Dr KS Wan (gwan1998@gmail.com)

Abstract

Introduction: An elevated serum urate level is

recognised as a cause of gouty arthritis and uric acid

stone. The level of serum uric acid that accelerates

kidney stone formation, however, has not yet been

clarified. This study aimed to find out if a high serum

urate level is associated with nephrolithiasis.

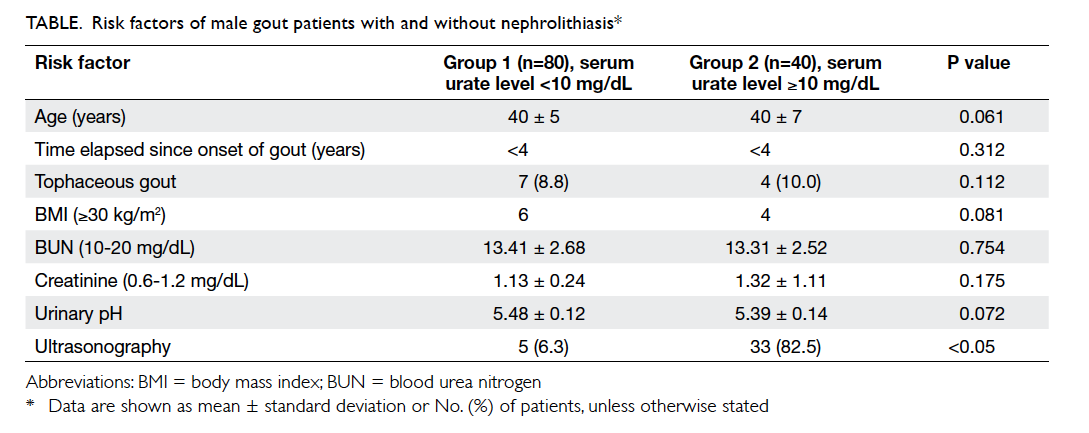

Methods: Patients were recruited from the

rheumatology clinic of Taipei City Hospital (Renai

and Zhongxing branches) in Taiwan from March

2015 to February 2016. A total of 120 Chinese male

patients with newly diagnosed gout and serum urate

concentration of >7 mg/dL and no history

of kidney stones were divided into two groups

according to their serum urate level: <10 mg/dL

(group 1, n=80) and ≥10 mg/dL (group 2, n=40).

The mean body mass index, blood urea nitrogen

level, creatinine level, urinary pH, and kidney

ultrasonography were compared between the two

groups.

Results: There were no significant differences in

blood urea nitrogen or creatinine level between

the two groups. The urine pH in both groups was

similar and not statistically significant. Kidney stone

formation was detected via ultrasonography in 6.3%

(5/80) and 82.5% (33/40) of patients in groups 1 and

2, respectively (P<0.05).

Conclusion: A serum urate level of ≥10 mg/dL

may precipitate nephrolithiasis. Further studies are

warranted to substantiate the relationship between

serum urate level and kidney stone formation.

New knowledge added by this study

- Hyperuricaemia is a risk factor for renal stone formation, which is associated with a substantially higher prevalence of nephrolithiasis on ultrasonography.

- Patients with gouty arthritis and serum urate level of ≥10 mg/dL should be advised to have renal ultrasonography.

Introduction

Over the past century, kidney stones have become

increasingly prevalent, particularly in more

developed countries. The incidence of urolithiasis in

a given population is dependent on the geographic

area, racial distribution, socio-economic status, and

dietary habits.1 In general, patients with a history of

gout are at greater risk of forming uric acid stones,

as are patients with obesity, diabetes, or complete

metabolic syndrome.2 Moreover, elevated serum

urate levels are known to lead to gouty arthritis,

tophi formation, and uric acid kidney stones.3

The incidence of uric acid stones varies between

countries and accounts for 5% to 40% of all urinary

calculi.4 Certain risk factors may be involved in the

pathogenesis of uric acid nephrolithiasis, including

low urinary volume and persistently low urinary pH.5

Calcium oxalate stones may form in some

patients with gouty diathesis due to increased

urinary excretion of calcium and reduced excretion

of citrate. In addition, relative hypercalciuria in

gouty diathesis with calcium oxalate stones may be

due to intestinal hyperabsorption of calcium.6 Most

urinary uric acid calculi are not pure in composition

and complex urates, sodium, potassium, and calcium

have been found together in various proportions.7 An

analysis of stones in gout patients in Japan showed

that the incidence of common calcium salt stones

was over 60%, while that of uric acid stones was only

30%.8 This implies that the disruption of uric acid

metabolism promotes not only uric acid stones, but

also calcium salt stones. Therefore, a high serum

urate level might be associated with nephrolithiasis

and this provided the rationale for this study.

Methods

Overall, 120 male gouty arthritis patients with newly diagnosed gout and serum urate concentration of >7 mg/dL, and without

previous kidney stone disease were allocated to one

of the two groups according to their serum uric acid

level: <10 mg/dL (group 1, n=80) and ≥10 mg/dL

(group 2, n=40). Patients were recruited from the

rheumatology clinic of Taipei City Hospital (Renai

and Zhongxing branches), a tertiary community

hospital in Taiwan, from March 2015 to February

2016. They had been newly diagnosed with gout

but had no clinical suggestions of renal stone

disease. The exclusion criteria included previously

treated gouty arthritis and current prescription of

urate reabsorption inhibitors. The patient’s age,

duration of gout arthritis, presence of tophi, body

mass index (BMI), blood urea nitrogen (BUN),

creatinine, urinary pH, and kidney ultrasonography

were all measured and analysed. This study has

been approved by the hospital’s Institutional Review

Board with informed consent waived.

Results for continuous variables were given as

means ± standard deviations. Student’s t test was

used to compare the physical characteristics that

were continuous in nature among the different

subject groups and the Chi squared test was used

to compare the difference in the stone detection

rate between the two groups. A P value of <0.05 was

regarded as statistically significant for two-sided

tests. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

(Windows version 12.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago [IL], US)

was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

The mean age of the two study groups was similar

(40 years). Family history of gout was present in

67.5% and 90% of groups 1 and 2, respectively. The

time elapsed since onset of gout was less than 4 years

in both groups. Tophaceous gout was found in 8.8%

in group 1 and 10.0% in group 2. The prevalence of

patients with a BMI of ≥30 kg/m2 was not statistically

significant between the two groups. Only 6% of

group 2 patients with kidney stones had a BMI of

>95th percentile. In most cases, urinary pH was less

than 5.5 in both groups and there were no abnormal

changes to BUN or creatinine levels. Interestingly,

the prevalence of kidney stones detected by

ultrasonography was 6.3% in group 1 and 82.5% in

group 2 (P<0.05). The sensitivity and specificity of

high serum urate level (>10 mg/dL) in predicting

kidney stones was 87% and 91%, respectively (Table).

Discussion

Gout is a common metabolic disorder characterised

by chronic hyperuricaemia, and serum urate level of

>6.8 mg/dL that exceeds the physiological threshold

of saturation. Urolithiasis is one of the well-known

complications of gout. We hypothesise that serum

urate level can be used as a predictive marker for

urolithiasis. Uric acid, a weak organic acid, has very

low pH-dependent solubility in aqueous solution.

Approximately 70% of urate elimination occurs

in urine, and the kidney plays a dominant role in

determining plasma level.9 A serum urate level of

>7 mg/dL is recognised as leading to gouty arthritis

and uric acid stone formation. Moreover, recent

epidemiological studies have identified serum

urate elevation as an independent risk factor for

chronic kidney disease, cardiovascular disease, and

hypertension.3 Impaired renal uric acid excretion is

the major mechanism of hyperuricaemia in patients

with primary gout.10 The molecular mechanisms

of renal urate transport are still incompletely

understood. Urate transporter 1 is an

organic anion transporter with highly specific urate

transport activity, exchanging this anion with others

including most of the endogenous organic anions

and drug anions that are known to affect renal uric

acid transport.10 11

Uric acid stones account for 10% of all kidney

stones and are the second most common cause of

urinary stones after calcium oxalate and calcium

phosphate. The most important risk factor for uric

acid crystallisation and stone formation is a low urine

pH (<5.5) rather than an increased urinary uric acid

excretion.12 The proportion of uric acid stones varies

between countries and accounts for 5% to 40% of all

urinary calculi.4 Uric acid homeostasis is determined

by the balance between its production, intestinal

secretion, and renal excretion. The kidney is an

important regulator of circulating uric acid levels

by reabsorbing about 90% of filtered urate and being

responsible for 60% to 70% of total body uric acid

factor underpinning hyperuricaemia and gout.13 Pure

uric acid stones are radiolucent but well visualised on

renal ultrasound or non-contrast helical computed

tomographic scanning; the latter is especially good

for detection of stones which are <5 mm in size.14

Nonetheless the reason why most patients with gout

present with acidic urine, even though only 20%

have uric acid stones, remains unclear. In a US study,

the prevalence of kidney stone disease was almost

two-fold higher in men with a history of gout than

in those without (15% vs 8%).15 Higher adiposity

and weight gain are strong risk factors for gout in

men, while weight loss is protective.15 An analysis by

Shimizu8 of stones in gout patients revealed that the

proportion of common calcium salt stones was over

60%, while that of uric acid stones was only about

30%. Overweight/obesity and older age associated

with low urine pH were the principal characteristics

of ‘pure’ uric acid stone formers. Impaired urate

excretion associated with increased serum uric acid

is also another characteristic of uric acid stone

formers and resembles patients with primary gout.

Patients with pure calcium oxalate stones were

younger; they had a low proportion of obese subjects

and higher urinary calcium.16

Conventionally, BMI was stratified as normal

(<25 kg/m2), overweight (25-29.9 kg/m2), or obese

(≥30 kg/m2). In males, the proportion of uric acid

stones gradually increased with BMI, from 7.1% in

normal BMI to 28.7% in obese subjects.17 The same

was true in females, with the proportion of uric acid

stones rising from 6.1% in normal BMI to 17.1% in

obese subjects.17 Studies found that BMI is associated

with an increased risk of kidney stone disease,

but with a BMI of >30 kg/m2, further increases do not

appear to significantly increase the risk of stone

disease.17 18 An independent association between kidney stone disease and gout strongly suggests that

they share common underlying pathophysiological

mechanisms.19

Three major conditions control the potential

for uric acid stone formation: the quantity of uric

acid, the volume of urine as it affects the urinary

concentration of uric acid, and the urinary pH.20 Two

major abnormalities have been suggested to explain

overly acidic urine: increased net acid excretion

and impaired buffering caused by defective urinary

ammonium excretion, with the combination resulting

in abnormally acidic urine.21 Urinary alkalisation,

which involves maintaining a continuously high

urinary pH (pH 6-6.5), is considered by some or

many to be the treatment of choice for uric acid

stone dissolution and prevention.20 In general, gout

is caused by the deposition of monosodium urate

crystals in tissue that provokes a local inflammatory

reaction. The formation of monosodium urate

crystals is facilitated by hyperuricaemia. In a study

by Sakhaee and Maalouf,21 being overweight and of

older age were associated with low urine pH and one

of the principal characteristics of pure uric acid stone

formation. Impaired urate excretion associated with

increased serum uric acid was another characteristic

of uric acid stone formation that resembles patients

with primary gout.

The limitations of this current study included

the lack of measurement of uric acid concentration

of urine in the participants, no further computed

tomographic scanning for kidney stones, no analysis

of stone composition, and limited representativeness

of the study subjects. For example, there were only

10 obese patients (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) in the analysis.

In this study, hyperuricaemia was a risk factor for

kidney stone formation. Patients with serum urate

level of >10 mg/dL should undergo ultrasound

examination to look for any nephrolithiasis.

Declaration

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

References

1. López M, Hoppe B. History, epidemiology and regional

diversities of urolithiasis. Pediatr Nephrol 2010;25:49-59. Crossref

2. Liebman SE, Taylor JG, Bushinsky DA. Uric acid

nephrolithiasis. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2007;9:251-7. Crossref

3. Edwards NL. The role of hyperuricemia and gout in kidney

and cardiovascular disease. Cleve Clin J Med 2008;75 Suppl 5:S13-6. Crossref

4. Shekarriz B, Stoller ML. Uric acid nephrolithiasis: current

concepts and controversies. J Urol 2002;168:1307-14. Crossref

5. Ngo TC, Assimos DG. Uric acid nephrolithiasis: recent

progress and future directions. Rev Urol 2007;9:17-27.

6. Pak CY, Moe OW, Sakhaee K, Peterson RD, Poindexter

JR. Physicochemical metabolic characteristics for calcium

oxalate stone formation in patients with gouty diathesis. J

Urol 2005;173:1606-9. Crossref

7. Bellanato J, Cifuentes JL, Salvador E, Medina JA. Urates in

uric acid renal calculi. Int J Urol 2009;16:318-21; discussion 322. Crossref

8. Shimizu T. Urolithiasis and nephropathy complicated with

gout [in Japanese]. Nihon Rinsho 2008;66:717-22.

9. Marangella M. Uric acid elimination in the urine.

Pathophysiological implications. Contrib Nephrol

2005;147:132-48.

10. Taniquchi A, Kamatani N. Control of renal uric acid

excretion and gout. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2008;20:192-7. Crossref

11. Yamauchi T, Ueda T. Primary hyperuricemia due to

decreased renal uric acid excretion [in Japanese]. Nihon

Rinsho 2008;66:679-81.

12. Ferrari P, Bonny O. Diagnosis and prevention of uric acid

stones [in German]. Ther Umsch 2004;61:571-4. Crossref

13. Bobulescu IA, Moe OW. Renal transport of uric acid:

evolving concepts and uncertainties. Adv Chronic Kidney

Dis 2012;19:358-71. Crossref

14. Wiederkehr MR, Moe OW. Uric acid nephrolithiasis: a

systemic metabolic disorder. Clin Rev Bone Miner Metab

2011;9:207-17. Crossref

15. Choi HK. Atkinson K, Karison EW, Curhan G. Obesity,

weight change, hypertension, diuretic use, and risk of gout

in men: the health professionals follow-up study. Arch

Intern Med 2005;165:742-8. Crossref

16. Negri AL, Spivacow R, Del Valle E, et al. Clinical and

biochemical profile of patients with “pure” uric acid

nephrolithiasis compared with “pure” calcium oxalate

stone formers. Urol Res 2007;35:247-51. Crossref

17. Daudon M, Lacour B, Jungers P. Influence of body size on

urinary stone composition in men and women. Urol Res

2006;34:193-9. Crossref

18. Semins MJ, Shore AD, Makary MA, Magnuson T, Johns R,

Matlaga BR. The association of increasing body mass index

and kidney stone disease. J Urol 2010;183:571-5. Crossref

19. Kramer HM, Curhan G. The association between gout

and nephrolithiasis: the National Health and Nutrition

Examination Survey III, 1988-1994. Am J Kidney Dis

2002;40:37-42. Crossref

20. Cicerello E, Merlo F, Maccatrozzo L. Urinary alkalization

for the treatment of uric acid nephrolithiasis. Arch Ital

Urol Androl 2010;82:145-8.

21. Sakhaee K, Maalouf NM. Metabolic syndrome and uric

acid nephrolithiasis. Semin Nephrol 2008;28:174-80. Crossref