© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

REMINISCENCE: ARTEFACTS FROM THE HONG KONG MUSEUM OF MEDICAL SCIENCES

The business of night soil collection

Moira Chan-Yeung, FHKCP, FRCPC (Internal Medicine)

Honorary Clinical Professor, The University of Hong Kong; Emeritus Professor of Medicine, University of British Columbia;

Member, Education and Research Committee, Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences Society

Until the end of the 19th century, Hong Kong was

known for its insanitary conditions, especially in

the Tai Ping Shan area, the Chinatown of Hong

Kong. Only the houses of wealthy Europeans had

water closets. Those of wealthy Chinese and some

Europeans had dry latrines but these were only for

men. Women and children of all classes used pots,

generally kept under the bed. For private houses,

night soil (human waste) was collected by female

coolies at night into buckets and the contents emptied

into junks that came alongside the waterfront at

specified points in the early hours of the morning.

The occupants of private houses paid a small sum for

the service, depending on the frequency of removal.

For daily removal (usually only for Europeans and

wealthy Chinese), the charge was HK$0.5 to $1 per

month; for removal every second day, the cost for

each family was HK$0.3 to 0.4 per month.

Working class men used public dry latrines.

Built and run by private persons as a business

venture, these latrines were invariably crowded and

unhygienic. The owner derived his profit from the

sale of the manure collected and from fees paid by

the users while the government obtained a share

of the profit by levying a tax of HK$0.60 per seat

per annum. The night soil from these latrines was

removed daily, in covered tubs, by the government

scavenging contractor, who provided collecting

junks for all night soil from public latrines,

government buildings, jails, and prisons as well as

from private houses. The boats carried the night soil

to Guangzhou or somewhere in China where it was

sold as fertiliser. The government contractor also

supplied the crew for street sweeping. This rubbish

was carried by boats to Lap Sap Wan (Gin Drinkers

Bay), and simply thrown onto the beach.1

The contractor received nothing from the

government. The people in the City of Victoria paid

nothing out of public funds for scavenging—the

value of the night soil collected was considerably

higher than the cost of performing this duty. Human

excreta were highly prized by the Chinese farmers as

manure. They were composted by mixing with ashes

or refuse, but often diluted with water according to

the nature of the crop to which they were applied.

The chief demand was for mulberry trees in the silk-producing

districts north of Guangzhou.1

This system of night soil collection persisted

during the Japanese occupation. The Second World

War disrupted transportation between Hong Kong

and the mainland and also farming in southern

China. Initially the collected night soil was dumped

into the harbour but later the Japanese built a

system of tanks at Castle Peak and smaller ones at

Tsuen Wan and Tai Po for the collected night soil to

‘mature’ (a process to reduce the risk of infection)

before selling on to farmers in the New Territories.2

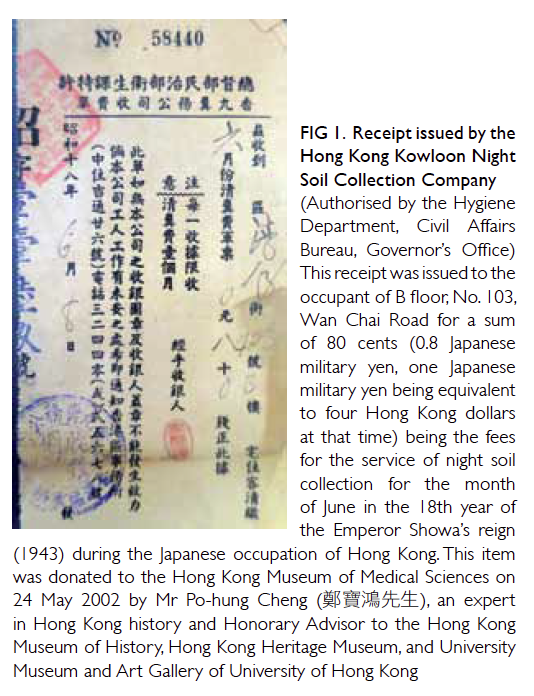

The receipt issued by the night soil collection

company to an occupant of a flat in Wan Chai Road

shows that night soil disposal for private houses was

more expensive than before the War (Fig 1).

Figure 1. Receipt issued by the Hong Kong Kowloon Night Soil Collection Company

(Authorised by the Hygiene Department, Civil Affairs Bureau, Governor’s Office) This receipt was issued to the occupant of B floor, No. 103, Wan Chai Road for a sum of 80 cents (0.8 Japanese military yen, one Japanese military yen being equivalent to four Hong Kong dollars at that time) being the fees for the service of night soil collection for the month of June in the 18th year of the Emperor Showa’s reign (1943) during the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong. This item was donated to the Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences on 24 May 2002 by Mr Po-hung Cheng (鄭寶鴻先生), an expert in Hong Kong history and Honorary Advisor to the Hong Kong Museum of History, Hong Kong Heritage Museum, and University Museum and Art Gallery of University of Hong Kong

Water was a rare commodity during the latter

part of the 19th century and early 20th century, and

had to be carried from public hydrants to the house.

The manual disposal of human excreta and the lack

of water and proper sewage disposal in Chinese

tenement houses led to the high prevalence of food- and

water-borne diseases such as cholera, dysentery,

and infective diarrhoeas and the ease with which

they could become epidemic.

Even before the Second World War, newly built

houses were required to have water closets. With

the replacement of old houses by new ones after the

War, fewer houses required night soil collection.

The process of modernisation was nonetheless slow;

in 1996 there remained some areas that required a

night soil collection service, although this was free

of charge.3

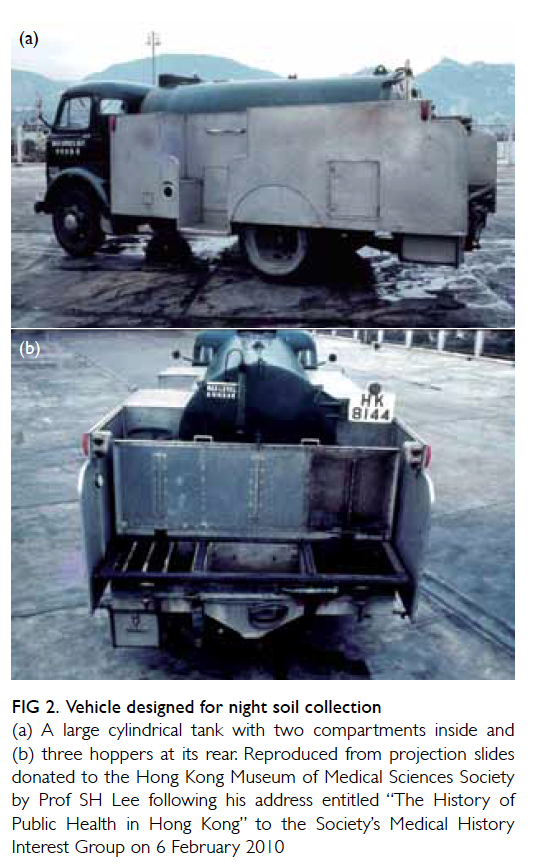

Interestingly this method of night soil removal

was useful during the 1961 to 1963 cholera outbreaks

as it enabled tracing of the source of infection and

contacts.4 By this time, night soil disposal was

‘modernised’ and more mechanised. The collected

night soil was emptied into special vehicles (清糞車)

designed for this purpose and in a hygienic manner

at fixed points along a number of set routes every

night. These vehicles discharged the night soil into

barges that either took the contents to storage tanks

for maturation, or dumped it if not required. Each

vehicle had a huge tank with two compartments, one

for night soil and one for water. At the back of the

vehicle were three hoppers: the first for the receipt

of night soil, the second for water and the third

for disinfecting fluid. The pails of night soil were

emptied into the first hopper, rinsed in the second,

and disinfected in the third (Fig 2).4

Figure 2. Vehicle designed for night soil collection

(a) A large cylindrical tank with two compartments inside and (b) three hoppers at its rear. Reproduced from projection slides donated to the Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences Society by Prof SH Lee following his address entitled “The History of Public Health in Hong Kong’ to the Society’s Medical History Interest Group on 6 February 2010

In January 1962, the Department of Health

began taking samples from the night soil vehicles

while they were discharging into the barges. Three

to four random samples were taken each week

from each vehicle. After a positive sample was first

reported, the vehicle was investigated with the object

of tracing the infection back to its source. Thus when

a sample from a vehicle was positive, each of the

loads collected by the vehicle was sampled; when

one load was positive, each pail forming that load

was sampled. When a pail was found to be positive,

the Health Officer took rectal swabs from all the

residents in the house or flat in which the latrine

was situated. The results of this study enabled the

Medical and Health Department to conclude that

the 1962 epidemic originated from several sources

and that there was a large number of symptomless

carriers among the population. Suitable preventive

measures were then instituted.5 Using night soil

surveillance, the Department was able to forecast

when and in what area a future outbreak of cholera

was likely to occur, to determine when the outbreak

was over and the colony was free from infection,

to trace the infection to its source, and to study its

spread within Hong Kong.6 Ironically, if the entire

population had had access to a water closet, this

valuable information would not have been available

and it would have been much more difficult to make

any accurate forecast of such an epidemic.

References

1. Mr. Chadwick’s reports on the sanitary condition of Hong Kong with appendices and plans. Eastern No 38. November, 1882. Hong Kong: Colonial Office; 1882: 18-21.

2. Selwyn-Clarke PS. Report on Medical and Health Conditions in Hong Kong. For the period 1 January 1941 to 31 August 1945. London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office; 1946.

3. Hong Kong 1997. A Review of 1996. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Government; 172.

4. Vandelinde PA. Observations on the spread of cholera in Hong Kong, 1961-1963. Bull World Health Organ 1965;32:515-30.

5. McCreery WC. The occurrence and treatment of El Tor cholera in Hong Kong, 1961-1963. Hong Kong: Department of Health; 1965.

6. Forbes GI, Lockhart JD, Bowman RK. Cholera and nightsoil infection in Hong Kong, 1966. Bull World Health Organ 1967;36:367-73.