Hong Kong Med J 2016 Aug;22(4):399.e1–3

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj164815

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

PICTORIAL MEDICINE

Neurocysticercosis in a young Indian male

Eugene PL Ng, MB, ChB;

Peter YM Woo, MB, BS, FHKAM (Surgery);

Alain KS Wong, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Surgery);

KY Chan, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Surgery)

Department of Neurosurgery, Kwong Wah Hospital, Yaumatei, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Eugene PL Ng (npl566@ha.org.hk)

A 33-year-old Indian male was hospitalised for

a 3-day history of headache and left lower limb

weakness in December 2014. He had experienced no

fever or seizures. He had visited New Delhi, India,

the year before. Physical examination revealed the

patient to be fully conscious with left lower limb

monoparesis. There was no sensory deficit. Computed

tomography (CT) revealed a superior parietal intra-axial

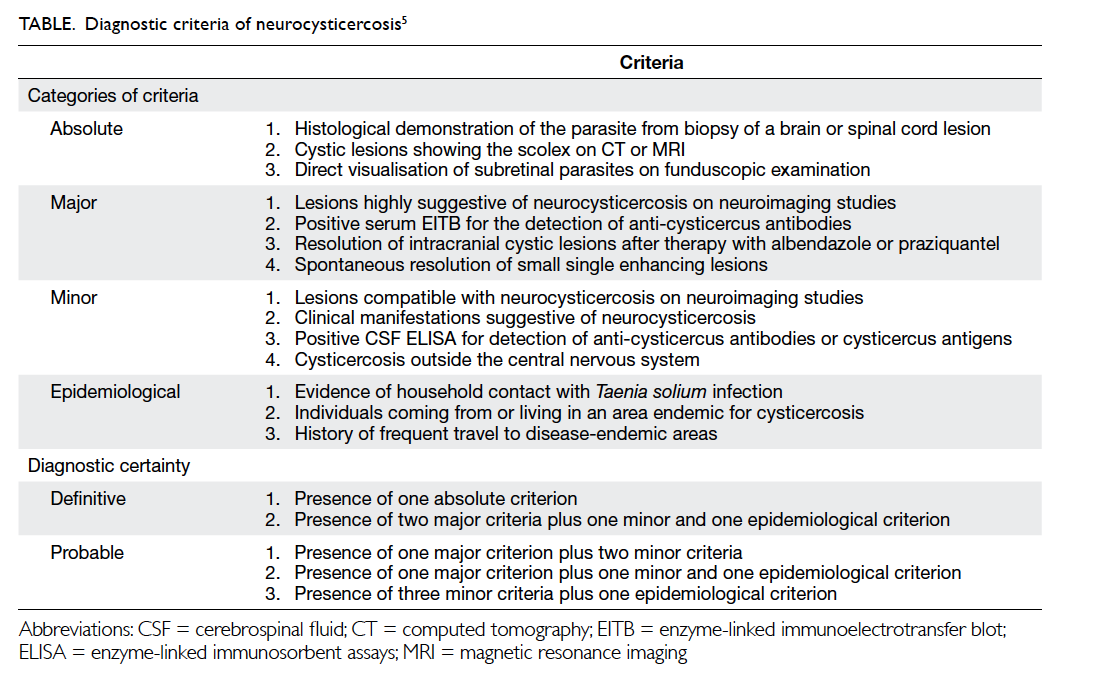

lesion with a calcified focus (Fig 1a). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) delineated a 2 x 1.5 x 1.5

cm circumscribed hypointense cystic lesion with a

contrast-enhancing wall and an eccentric intracystic

signal with perilesional oedema (Figs 1b to 1d). Differential diagnoses included neurocysticercosis,

brain abscess, brain metastasis, and malignant

glioma. Craniotomy for excision was performed

in view of the possibility of malignancy and the

surgically accessible superficial location of the lesion.

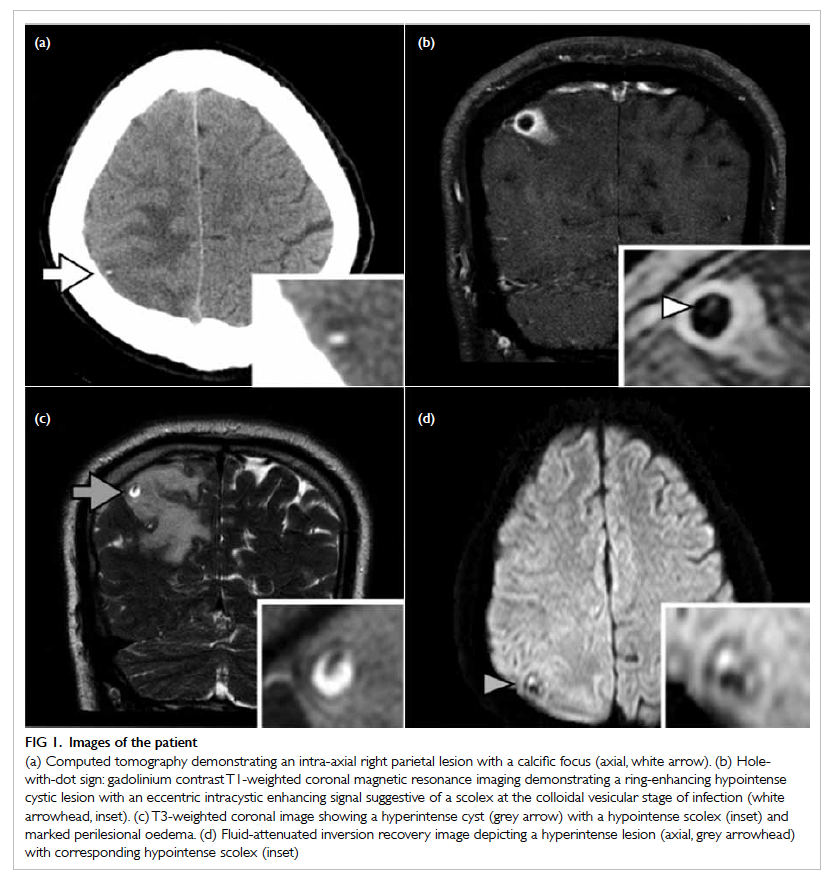

Intra-operatively, a firm capsular mass containing

thick opaque material was seen (Fig 2a). Histology revealed a cysticercus within a fibrous capsule,

compatible with the diagnosis of neurocysticercosis

(Figs 2b and 2c). A 2-week course of oral albendazole was commenced and the patient was discharged with

full recovery.

Figure 1. Images of the patient

(a) Computed tomography demonstrating an intra-axial right parietal lesion with a calcific focus (axial, white arrow). (b) Hole-with-dot sign: gadolinium contrast T1-weighted coronal magnetic resonance imaging demonstrating a ring-enhancing hypointense cystic lesion with an eccentric intracystic enhancing signal suggestive of a scolex at the colloidal vesicular stage of infection (white arrowhead, inset). (c) T3-weighted coronal image showing a hyperintense cyst (grey arrow) with a hypointense scolex (inset) and marked perilesional oedema. (d) Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery image depicting a hyperintense lesion (axial, grey arrowhead) with corresponding hypointense scolex (inset)

Figure 2. Intra-operative photographs and photomicrographs of the patient

(a) Intra-operative photographs of resected neurocysticercus with a fibrous wall containing thick opaque material. (b) The typical colloid cyst membrane (white arrow; H&E; original magnification, x 40). (c) Taenia solium scolex comprises four suckers (black arrow) and a double row of hooks (grey arrow) for host intestinal wall attachment (H&E; original magnification, x 100)

Neurocysticercosis is the most common

parasitic infection of the central nervous system

(CNS) caused by the larval form of Taenia solium.

The peak age of incidence is between 25 and 35

years1 and the condition is endemic to the Indian

subcontinent, coastal North Africa, sub-Saharan

Africa, Latin America, and China. The main mode of

transmission is by faecal-oral ingestion of tapeworm

embryos.1 2 Consumption of contaminated poorly

cooked pork is a less-frequent alternative source of

infection since pigs are intermediate hosts.2 3 Within

72 hours of ingestion, larvae known as oncospheres

are released and pass through the intestinal wall into

the circulation, subsequently depositing in the CNS,

retina, and skeletal muscle as cysticerci.1 2 The parasite can remain viable in the brain for several years after

which it undergoes calcific degeneration.3 In endemic

areas, the most common presentation is epilepsy,

responsible for 30% of cases.1 Focal neurological

deficits may occur including cranial nerve palsy

due to basal meningitis. Obstructive hydrocephalus

develops when lesions occupy the fourth ventricle.1 2

Characteristic radiological features include

dystrophic calcification on CT imaging, cyst wall

contrast enhancement on T1-weighted MRI and

identification of the pathognomonic scolex, an

eccentric focus of enhancement representing

the tapeworm’s head, best delineated with fluid-attenuated

inversion recovery sequences (hole-with-dot sign).3 4 Brain abscess or metastases are important differential diagnoses as they are

also similarly located at the grey-white matter

junction of the middle cerebral artery distribution,

associated with disproportionately significant

perilesional cerebral oedema and classically exhibit

heterogeneous contrast enhancement. Malignant

glioma was less likely in our patient since they are

morphologically more infiltrative, and the present

lesion was well-circumscribed. For this patient,

the major distinguishing feature that supported a

diagnosis of neurocysticercosis was the presence of

dystrophic calcification on CT and, in retrospect,

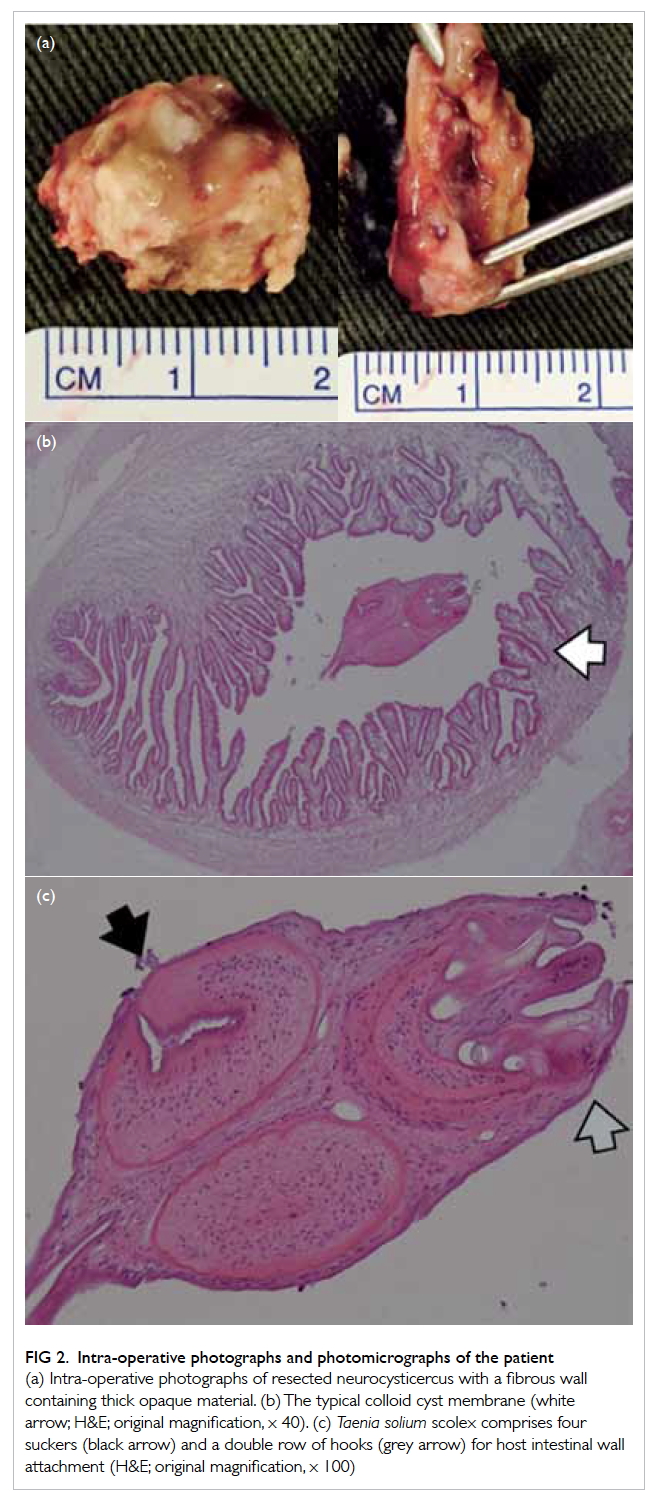

the presence of a scolex on MRI. Absolute criteria

for a definitive diagnosis are either histological

parasitic proof, imaging demonstration of a scolex,

or subretinal parasites on fundoscopy (Table5).

Serological enzyme-linked immunoelectrotransfer

blot detection of anti-cysticercus antibodies or

cerebrospinal fluid enzyme-linked immunosorbent

assays are adjunctive investigations.1 6 Management of

active neurocysticercosis includes antiepileptic drug

administration, anti-inflammatory glucocorticoid

therapy, and definitive antiparasitic therapy with

albendazole (15 mg/kg per day) or praziquantel

(50 mg/kg per day) for 2 to 4 weeks.1 Surgical

excision is reserved for cysts that cause mass effect,

hydrocephalus, or if the diagnosis is unclear.2

In an era of increasing migration and

international travel, patients from developing

countries who present with seizures, raised

intracranial pressure symptoms, or focal

neurological deficit should be suspected of having

neurocysticercosis when characteristic imaging

findings are identified. In probable cases, a trial of

antiparasitic therapy is recommended with serial

scans arranged to monitor treatment response.

References

1. Garcia HH, Nash TE, Del Brutto OH. Clinical symptoms,

diagnosis, and treatment of neurocysticercosis. Lancet

Neurol 2014;13:1202-15. Crossref

2. Zymberg ST. Neurocysticercosis. World Neurosurg

2013;79(2 Suppl):S24.e5-8.

3. Dhesi B, Karia SJ, Adab N, Nair S. Imaging in

neurocysticercosis. Pract Neurol 2015;15:135-7. Crossref

4. Lerner A, Shiroishi MS, Zee CS, Law M, Go JL. Imaging

of neurocysticercosis. Neuroimaging Clin N Am

2012;22:659-76. Crossref

5. Del Brutto OH, Rajshekhar V, White AC Jr, et al. Proposed

diagnostic criteria for neurocysticercosis. Neurology

2001;57:177-83. Crossref

6. Gekeler F, Eichenlaub S, Mendoza EG, Sotelo J, Hoelscher

M, Löscher T. Sensitivity and specificity of ELISA and

immunoblot for diagnosing neurocysticercosis. Eur J Clin

Microbiol Infect Dis 2002;21:227-9. Crossref