Hong Kong Med J 2016 Aug;22(4):372–81 | Epub 20 May 2016

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj154686

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

REVIEW ARTICLE

Oral health of Hong Kong children: a historical and epidemiological perspective

Gillian HM Lee, FCDSHK (Paediatric Dentistry), FHKAM (Dental Surgery);

Harry N Pang, FCDSHK (Orthodontics), FHKAM (Dental Surgery);

Colman McGrath, FFDRCS (Ire), PhD (Eng);

Cynthia KY Yiu, FHKAM (Dental Surgery), FCDSHK (Paediatric Dentistry)

Faculty of Dentistry, The University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Gillian HM Lee (lee.gillian@gmail.com)

Abstract

Objective: To provide a historical and

epidemiological overview of the oral health of Hong

Kong children.

Methods: Literature published before 2014

related to the oral health of Hong Kong children,

supplemented with information accessed from

government-archived oral health reports, was

sourced using electronic databases and hand

searches. Dental caries experience, periodontal

health, enamel defects, and malocclusion of Hong

Kong children were reviewed.

Results: A decline in the prevalence and extent

of dental caries was observed among Hong Kong

schoolchildren and adolescents after the 1960s.

Among preschool children, however, dental caries

remains common and the extent appears to have

increased. The periodontal health of Hong Kong

children remains unsatisfactory. Recently, enamel

defects/dental fluorosis have considerably reduced.

Information about malocclusion in Hong Kong

children is limited.

Conclusions: Since the 1960s, following public

health policies, health promotion activities, and

the introduction of a School Dental Care Service,

improvements in the oral health of schoolchildren

are evident. Nonetheless, the oral health of preschool children

remains a concern. Policies and

practices to improve the oral health of preschool children

in Hong Kong are required.

Introduction

Over the past 50 years, a number of dental public

health measures and policies have been established

by the government in Hong Kong to help improve

the oral health of the population. Children have

been the focus for many of these dental public health

practices since the 1960s and these have included

prevention strategies, oral health education, and the

provision of the School Dental Care Service (SDCS).

Historical development of Hong Kong’s public health measures for children

Water fluoridation is one of the most successfully

implemented dental public health measures in Hong

Kong. The project was launched in 1961 and has

remarkably reduced the prevalence of dental caries

in Hong Kong.1 All areas with a centralised water

supply are fluoridated. Prior to its implementation,

the natural fluoride concentration of drinking

water in Hong Kong was less than 0.13 parts per million (ppm). Several adjustments have been made

to the water fluoride level in Hong Kong since its

implementation: from 0.7 ppm for summer months

and 0.9 ppm for winter months in 1961, to 1 ppm in

1967; then reduced to 0.7 ppm in 1978; and further to

0.5 ppm in 1988 because of concerns of an increased

prevalence of dental fluorosis in the population.

In late 1979, the SDCS was introduced to

provide prevention and dental treatment to primary

schoolchildren in Hong Kong. The SDCS also aims

to promote oral health by delivering oral health

education to schoolchildren. Preschool children

in Hong Kong are not routinely eligible for the

SDCS. They receive oral health care and treatment

largely from dentists working in the private sector.

Oral health education for preschool children was

introduced through the ‘Brighter Smiles for the New

Generation’ programme by the government in 1993.

This programme promotes oral health awareness

by educating children aged under 6 years about

good oral health–related behaviour. It also aims to

increase their teachers’ and parents’ oral health care

knowledge.

The community is served by registered

professional oral health care personnel. The Faculty

of Dentistry at the University of Hong Kong was

established in 1981 and began training dentists and

supporting dental personnel in the same year. More

than one third of local practising dentists have been

educated in Hong Kong.2 The number of practising

dentists currently serving the community has

increased to about 2310 personnel, a per capita ratio

of 1:3125.3 Before 1973, there were only about

440 practising dentists, a per capita ratio of 1:9000. In

the past, it was often only the economic affluent who

sought treatment from private dental practitioners.

For many others, teeth were considered a dispensable

commodity.2 Although this situation has improved,

access to dental care for the Hong Kong population

remains inadequate.

Oral health care products (fluoridated

toothpaste, mouth rinses, toothbrushes, and floss)

are now widely available in Hong Kong.4 These easily

accessible fluoride-containing products provide an

additional benefit to the oral health of the Hong

Kong population. Most locally available toothpastes

have a fluoride concentration of 1000 to 1500 ppm,

while those for children have 600 ppm. Mouth rinse

with 0.05% sodium fluoride is also freely available,

though its use among children is not common and

it is not recommended for the very young.

Over the years, dentistry in Hong Kong has

advanced and oral health care has greatly improved

under several government public health policies.

Although children have been the primary target

of such initiatives, information and review of the

effects of the changes and trends in the oral health

of Hong Kong children are limited. This is in part due

to the limited dissemination of findings, particularly

those of earlier government reports. Understanding

the trends and current oral health condition of

Hong Kong children is important. It can provide a

historical and epidemiological overview of dental

activity and inform the planning of future public

health measures, prevention, and services for

children. It may also help set future oral health

targets and specific goals.

This paper reviews all available oral health

epidemiological data and information of Hong

Kong children from published literature before 2014

through electronic database searches, supplemented

with information accessed from government-archived

oral health reports. Reference lists of

articles retrieved from the electronic databases were

hand-searched for any other articles that might

provide information relevant to the objectives of

this paper. Major oral health problems of Hong

Kong children—including dental caries experience,

periodontal health, enamel defects, malocclusion,

and orthodontic treatment need—are described.

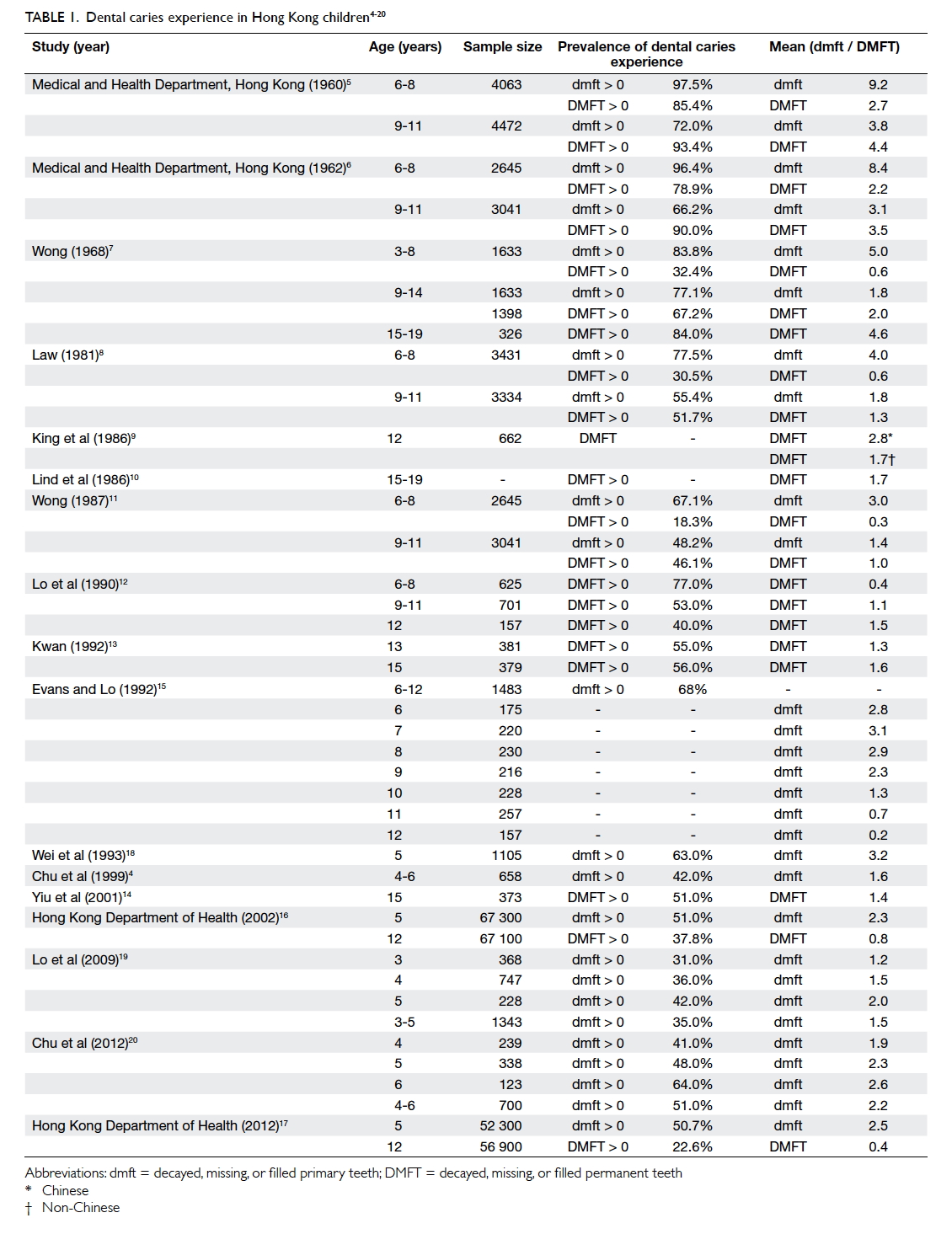

Dental caries experience

A number of population-based oral epidemiological

studies involving children have been conducted in

Hong Kong since the 1960s. Available epidemiological

data regarding dental caries experience and the

extent/severity of dental caries among Hong Kong

children are summarised in Table 1.4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 These studies

employed different sampling methods as criteria of

assessment differed prior to the 1970s. More recent

surveys have followed World Health Organization’s

criteria for caries assessment.

Dental caries experience of schoolchildren and adolescents (aged 6-18 years)

To date, there are 13 population-based

epidemiological studies reporting the prevalence

and extent of dental caries experience among Hong

Kong schoolchildren and adolescents. A remarkable

decrease in caries experience and severity among

schoolchildren and adolescents has been observed

since the 1960s.

The earliest report of dental caries experience

among schoolchildren and adolescents was carried

out in 1960, a year before the implementation of

water fluoridation.5 The epidemiological findings

gave cause for concern. Almost all children aged 6

to 11 years who participated in the study (aged 6-8: 97.5%; aged 9-11: 93.4%) had dental caries. The mean

number of decayed, missing, or filled permanent

teeth (DMFT) in 6-8-year-olds and 9-11-year-olds was 2.7 and

4.4, respectively; the mean decayed, missing, or filled

primary teeth (dmft) in 6-8- and 9-11-year-olds was

9.2 and 3.8, respectively. Decayed teeth constituted

the major component (>90%) of the dmft/DMFT

index in both dentitions, and extracted and filled

teeth components were minimal. This signified

that there were no systematic dental care services

available at the time and with limited preventive

measures.

In 1962, the second population-wide oral

health survey was conducted using similar sampling

methodology to the 1960 survey,6 1 year after the

implementation of water fluoridation. There was a

reported slight decrease in the prevalence of dental

caries experience (for those aged 6-8 years: 96.4%; for

those aged 9-11 years: 90.0%). The mean dmft and DMFT

showed a significant decline of approximately 20%

(mean DMFT: 2.2 for those aged 6-8 years and 3.5 for

those aged 9-11 years; mean dmft: 8.4 for those aged 6-8 years

and 3.1 for those aged 9-11 years). As in the 1960 survey,

decayed teeth constituted the major component of

the DMFT, showing limited change in the provision/usage of dental care services. As this survey was

conducted a year after water fluoridation, the

decrease in dental caries could not be fully explained

by exposure to fluoridated water. No report on the

difference in dmft/DMFT among children who

had received fluoridated water for the whole time,

intermittently, or not at all was provided.

The third oral health survey of Hong Kong was

completed in 1968, 7 years after the introduction of

water fluoridation.7 The sampling method differed to

the earlier surveys. Subjects aged 3 to 54 years were

selected. The dental caries experience in the primary

dentition was 83.8% (mean dmft: 5.0) for 3-8-year-olds, whereas the dental caries experience in the

permanent dentition was 67.2% (mean DMFT: 2.0)

for 9-14-year-olds, and 84.0% (mean DMFT: 4.6) for

15-19-year-olds. It represented a significant decrease

in both caries experience and its extent among

children when compared with previous surveys.

This favourable change was attributed to water

fluoridation as there were no other widely available

caries preventive measures or systematic dental care

services in the 1960s.

In 1980, another population-based dental

health survey collected baseline data for future

evaluation of the SDCS.8 The majority of

schoolchildren (aged 6-11 years) examined were caries-free

in their permanent dentition. The mean DMFT

was <1 for children aged <9 years and 1.5 for 11-year-olds. The caries experience in the primary dentition

of the children was high, however. The mean dmft

for 6-year-olds was 4.3. The number of extracted and

filled teeth for both dentitions was low. More than

90% of decayed teeth were untreated, indicating the

lack of utilisation of dental services and a very high

unmet treatment need.

The epidemiological studies conducted in the

1980s after the commencement of SDCS to monitor

the effect of fluoride on dental caries experience

of Hong Kong schoolchildren and adolescents

after over 20 years of water fluoridation showed a

further decrease in caries experience and severity.

The reported mean DMFT of schoolchildren and

adolescents in these surveys ranged from 0.3 to 2.89 10 11 12

and the mean dmft was 2.2.11 The caries experience

was >65% in primary dentition and 18.3% to 77% in

permanent dentition.11 12 The major component of

the DMFT of the children of this time was decayed

teeth, demonstrating that there was still a high

unmet need for dental services, although the SDCS

was already enacted. Caries was mostly experienced

in molar teeth for children aged 9 to 12 years.

The caries prevalence and extent among Hong

Kong schoolchildren and adolescents continued to

show improvements. Kwan13 reported the first survey

of schoolchildren aged 13 and 15 years who joined

the SDCS in 1992. The dental caries experience

was approximately 55%, with a mean DMFT of 1.3

for 13-year-olds and 1.6 for 15-year-olds. The result

corresponded to a study by Yiu et al14 that reported

a caries experience of 51% and a mean DMFT of 1.4

among 15-year-olds. In 1992, Evans and Lo15 also

studied the effects of the SDCS on the dental status

of primary teeth among a sample of Chinese children

aged 6 to 12 years. The caries experience was 68%,

with dmft indices for 6-, 7-, 8-, 9-, and 10-year-olds being

2.8, 3.1, 2.9, 2.3, and 1.3, respectively. The ratio of

decayed-to-filled teeth decreased from 3.2 at age 6

to 1.0 at age 9. The mean number of filled teeth was

the major component of the dmft index in these

surveys, indicating that many children had received

dental care.

The Hong Kong SAR Government conducted a

population-based survey of the oral health status of

12-year-old children in 2001 and 2011.16 17 More than

one-third (37.8%) of the children in 2001 had a caries

experience in their permanent dentition and in 2011,

22.6% of the children had a caries experience. The

extent/severity of caries was low (mean DMFT: 0.8 in

2001, 0.4 in 2011). Most of the decay experience was

attributed to the filled component. The proportion

of untreated decay was also rather low, with only

5.4% reported to have untreated decayed teeth

in 2011. This positive development in oral health

was associated with reported better oral health

knowledge and oral care habits in both parents and

children. A large number of the participants claimed

they had regular dental check-ups.

In the past 50 years, for Hong Kong

schoolchildren and adolescents, the prevalence

of dental caries experience in permanent teeth

has reduced from more than 90% (in the 1960s) to

approximately 50% in the 1980s/90s and to less than

25% currently. The mean number of DMFT has also

declined from over 4 in the 1960s to approximately 2

in the 1980s/90s, and to less than 1 currently.

Dental caries experience of preschool children (aged ≤5 years)

There were seven epidemiological studies reporting

dental caries experience among preschool children.

Improvement among preschool children is less since

the 1960s, compared with improvements among

schoolchildren and adolescents and it remains a

considerable problem.

The earliest oral health survey that involved

young children was the population-based survey

conducted in 1968.7 The prevalence of dental caries

experience among 3-8-year-old children at that

time was over 80%, with a dmft of 5. One quarter

of the primary teeth of the children were decayed.

The second report of preschool children caries

experience in Hong Kong was drawn up by Wei

et al.18 Conducted between 1986 and 1988 among

approximately 10% of 5-year-old children, the

percentage of children with caries in their primary

dentition was 63%. The mean dmft was 3.2. Dental

caries experience was higher for children from

socio-economically disadvantaged families. Over

70% of the children had never visited a dentist.

The caries experience of Hong Kong preschool children

further decreased to about 50%

in the late 1990s.4 The mean dmft of children

(4-6-year-olds) was 1.6. More than 90% of the dmft score

was attributed to decayed untreated teeth. Similar

to the findings of Wei et al,18 the children’s caries

experience was associated with underprivileged

socio-economic background, and parental educational level, dental knowledge, and attitudes.

In the recent decade, no great changes among

preschool children caries status have been observed.

The caries prevalence in preschool children remains

similar, with a reported prevalence of 35% to

51%.16 17 19 20 The extent/severity of caries, however,

showed a slight increase when compared with the

late 1990s (mean dmft of children aged 3-5 years ranged

from 1.5 to 2.5). Over 90% of the decayed teeth of

the children were untreated. Almost one tenth of

the children presented with abscess, with a higher

percentage reported in the 2011 survey than in the

2001 survey.16 17 These recent surveys also found

that children’s caries experience was associated with

their place of birth, socio-economic background,

and dietary habits.

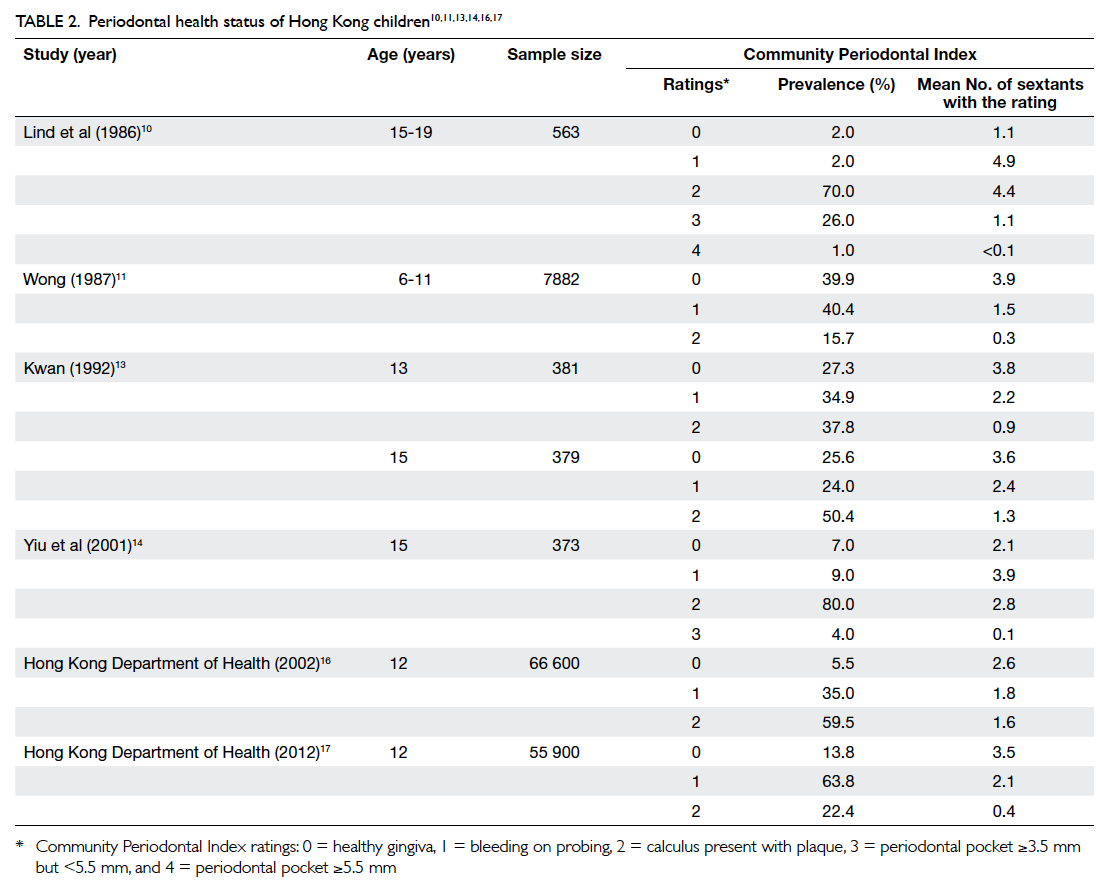

Periodontal health status

Detailed information about the periodontal status

of Hong Kong children is less readily available when

compared with information about dental caries

experience. Different assessment criteria have been

used to assess periodontal health among children

and adolescents, making it difficult to compare

surveys.

The earliest report of the periodontal health

status of Hong Kong children (aged 3-19 years) was

drawn up by Wong in 1968.7 Wong7 reported that

“oral hygiene was only fair in 70% of the children”

and that “over 60% of the children had inflamed

gingiva, and material alba was found on over 90%

of the teeth surfaces”. Inflamed gingiva (gingivitis)

is the reversible and non-destructive form of

periodontal disease. This suggested that the children

had poor periodontal health, though the criteria of

assessment were not defined.

Law8 provided more specific details about the

periodontal health status of 5-14-year-old Hong

Kong children. Approximately 85% were reported

to have soft deposits (assume plaque), of whom approximately one (19.2%) in five had ‘intensive gingivitis’ (inflamed gingiva). Calculus was observed among over a

quarter (26.4%) of the children, and the percentage

of calculus deposits increased with age.

Epidemiological studies conducted in the late

1980s employed the Community Periodontal Index

(CPI) to assess the periodontal health status. It is

the standard epidemiological index for assessing

periodontal health,21 and results of the surveys were

comparable. The epidemiological studies reporting

periodontal health status of Hong Kong children

using the CPI are shown in Table 2.10 11 13 14 16 17 The

majority reported periodontal health status of

adolescents. Among adolescents (13-18 years old),

two of three studies10 13 14 reported that less than

10% had ‘healthy’ periodontal status (CPI=0) and

more than half had evidence of calculus in some

parts of the mouth (CPI=2). This showed that the

periodontal health of Hong Kong adolescents was

unsatisfactory.

For Hong Kong schoolchildren, the first

detailed report of their periodontal health status

was conducted by Wong11 among 7882 primary

schoolchildren (aged 6-11 years) in 1987. More than

half of the sextants (3.9) of the children had healthy

gingiva (CPI=0). Nonetheless, more than half

(56.1%) of the children had bleeding gingiva (CPI=1) or calculus deposits (CPI=2).

Two population-based oral health surveys

among schoolchildren (12-year-old children)

were conducted by the government in 2001 and

2011.16 17 The 2011 survey showed an improvement

in periodontal health status. More schoolchildren

were found to have healthy gingiva (CPI=0) in 2011: 13.8% compared with 5.5% in the 2001 survey; and

less children had calculus deposits (CPI=2) in 2011: 22.4% compared with 59.5% in the 2001 survey. Of

note, more than half of their sextants had either

bleeding gingiva or calculus deposits in 2001 and an

average of two of the sextants had these problems in

2011.

Studies that applied the Visible Plaque Index to assess periodontal health of Hong Kong

preschool children are shown in Table 3.16 17 22 Such Index was introduced by Ainamo and Bay23 as a

standardised assessment of oral hygiene status. It is

simple and reliable to use and has been employed in

surveys as a proxy of gingival health, representing

the site prevalence of ‘clearly visible dental plaque’

at the gingival margin. The oral hygiene of the preschool children

in Hong Kong was poor.16 17 22 Almost all 5-year-old children (97%) had at least one site

with ‘clearly visible dental plaque’.16 17 The mean percentage of tooth surfaces with visible dental

plaque was 22.1% in 2011 and 23.5% in 2001. A study

conducted among 531 children aged 3 to 4 years in

2009, however, reported that 49.7% of the tooth

surfaces had visible plaque.22 In general, the gingival

condition and tooth cleanliness of both schoolchildren

and preschool children were unsatisfactory and

required much improvement.

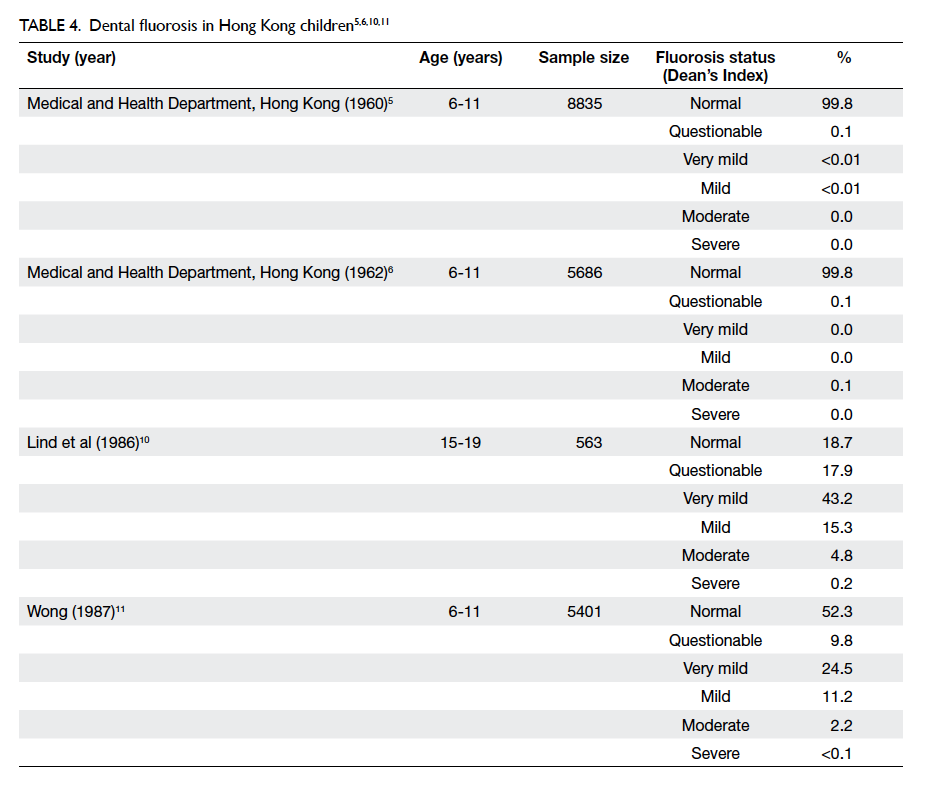

Dental fluorosis/enamel defects

Dental fluorosis consequent to exposure to fluoride

may develop during the formation of teeth in young

children. Table 4 outlines the studies reporting dental fluorosis using Dean’s Index in Hong

Kong to date.5 6 10 11 Epidemiological studies reporting

dental fluorosis showed that the level was low in the

1960s.5 6 Nearly all examined children aged 6 to 11 years

had ‘normal’ enamel. Less than 1% were assessed as

having a ‘mild’ or ‘questionable’ degree of fluorosis in

1960 or having a ‘moderate’ or ‘questionable’ degree

of fluorosis in 1962.

Dental fluorosis was reported to be more

prevalent in the 1980s, particularly among

adolescents.10 11 Over 80% of the 15-19-year-olds in the study by Lind et al10 exhibited signs of dental

fluorosis; and approximately 50% of the 6-11-year-olds in the study by Wong11 showed various degrees of dental fluorosis.

King24 reported the prevalence of enamel

defects among a random sample of 12-year-old

children in Hong Kong. The prevalence of teeth

with opacities was 99.6%; 82.8% had evidence of

hypoplasia and 16.6% had discoloured teeth. The

author believed that many of the enamel defects were

likely to be related to dental fluorosis. The findings in

the 1980s suggested a marked increase in the level

of dental fluorosis since the introduction of water

fluoridation in the 1960s and it was then advocated

to lower the water fluoridated level.1 The prevalence

declined considerably over the decades when the

level of fluoride in the water supply was adjusted and

lowered.25 At present the level of water fluoridation

is optimal at 0.5 ppm. The trend of decreasing dental

fluorosis prevalence was evident in the study by

Evans and Stamm.26 The prevalence decreased from

64% to 47% across the cohort of children from older

(aged 12) to younger (aged 7) born before and after

reduction of fluoride level to 0.7 ppm in 1978.

The prevalence and severity of developmental

defects of enamel (DDE) have also been studied.

Cross-sectional surveys showed that the prevalence

of diffuse opacities among random samples of

12-year-old children (based on maxillary incisors and

assessed using standardised intra-oral photographs)

declined from 89.3% in 1983 to 32.4% in 2001, but

increased to 42.1% in 2010.27 The mouth prevalence

of DDE among maxillary incisor teeth of the

children also decreased from 92.1% in 1983 to 35.2%

in 2001.28 Wong et al29 also reported the prevalence

of DDE among Hong Kong 12-year-old children

at 90% in a 2010 cohort study (89.5% had diffuse

opacities, 8.6% demarcated opacities, and 1.8%

hypoplasia), using the modified version of the DDE

index by FDI (Fédération Dentaire Internationale)

to diagnose DDE.30 The prevalence of molar incisor

hypomineralisation was reported as 2.8% among

Primary 6 Chinese schoolchildren in a 2006

retrospective study.31

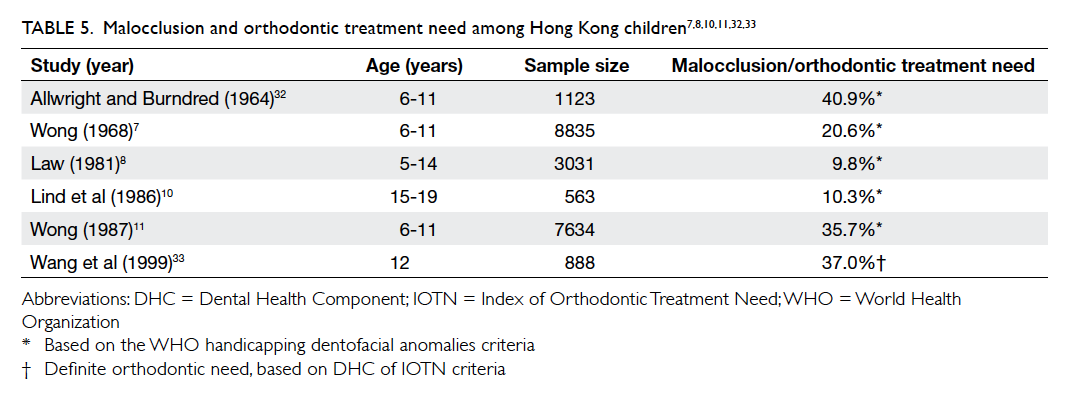

Malocclusion and orthodontic treatment need

Epidemiological data on malocclusion and

orthodontic treatment need among Hong Kong

children are scant. Relatively few surveys have

been conducted since the 1960s but details of the

available studies are shown in Table 5.7 8 10 11 32 33 The studies were heterogeneous in terms of criteria

used to assess dentofacial anomalies that require

orthodontic intervention and age of the sampled

children. Comparison and description of estimates

of orthodontic treatment are difficult.

Earlier epidemiological studies of malocclusion

and orthodontic treatment need among Hong Kong

children suggested that dentofacial deformities

requiring treatment intervention was ≤20%. More

recent studies suggest orthodontic treatment need to

be closer to 40%. It is estimated that about one third

of children have a ‘definite’ orthodontic treatment

need. A report by Allwright and Burndred32

provided the first published study of the prevalence

of dentofacial anomalies requiring treatment

intervention among Hong Kong children. Their

study included 31% of the 6-11-year-old children

who participated in the 1962 oral health survey6

and reported that 40.9% of the children exhibited

certain dentofacial anomalies. The most common

malocclusions were crowding (20.3%), maxillary

overjet (14.5%), mandibular overjet (8.1%), overbite

(6.9%), spacing (2.9%), and open bite (1.1%). The

prevalence of handicapping dentofacial anomalies

was higher among those aged 9 to 11 years (54.2%)

than among those aged 6 to 8 years (36.4%).

Wong7 reported that approximately one (20.6%)

in five of 5-14-year-old children had dentofacial

anomalies that required dental treatment. The most

common dentofacial anomaly was crowding (17.6%),

followed by maxillary overjet (9.5%), overbite (4.2%),

mandibular overjet (2.7%), spacing (1.1%), and

open bite (0.7%). The prevalence of anomalies was

higher among those aged 9 to 15 years (28.2%) than

among those aged 5 to 8 years (16.4%). The reduction

in the prevalence estimates of malocclusion when

compared with the 1960 study6 could be due to the

participation of different examiners (orthodontists

in 1960 study vs general dental practitioners in 1968

study) and the wider age range of children involved

in the 1968 survey.7

In the 1980s, the reported prevalence of dentofacial

anomalies that required treatment was 10%

to 36%.8 10 11 The percentage of children with cleft

palates and/or lip was approximately 0.2%, with a

slightly higher proportion of children with cleft lip.8 11 The most common reported dentofacial anomalies

that required treatment were crowding (3.3-18.5%),

maxillary overjet (2.8-5.1%), cross-bite (2.4-7.5%),

reverse overjet anomaly (1%), deep overbite (0.9-5.4%), and open bite (0.5-1.9%). The prevalence

of dentofacial anomalies was higher among 9-11-year-old children (13-38%) compared with 6-8-year-old children (6.7-34%).8 11 Among all the reported studies, only Wang et al33 used DHC IOTN (Dental

Health Component of the Index of Orthodontic

Treatment Need)34 to assess treatment

need. The prevalence of malocclusion was estimated

to be 88% and over a third (37%) of the study

sample were deemed to have a ‘definite’ orthodontic

treatment need and 33% had a moderate need.

Discussion

The introduction of water fluoridation in the 1960s

resulted in improvements in dental caries in Hong

Kong. Prior to its implementation, nearly all children

in the population had dental caries, with a high mean

number of decayed, missing, or filled teeth because

of tooth decay (mean dmft of 9.2 and DMFT of

4.4).5 The implementation of water fluoridation in

the community led to a gradual decline in the caries

experience and severity in children, as confirmed by

the first three oral epidemiological studies in Hong

Kong.5 6 7 The caries experience remained constant (plateaued) with approximately 50% of preschool children

and 20% to 40% of schoolchildren since 1980s/1990s

having a dental caries experience. This indicates

that children in Hong Kong are benefiting from the

continual effects of water fluoridation as well as

exposure to fluoride from other sources, together

with changing living conditions, lifestyles, and

improved oral self-care habits in recent decades. The

stable caries prevalence in recent years signifies that

dental caries in children is controlled to a certain

degree, but still remains prevalent, however.

Despite great improvements in the oral health

of Hong Kong children over the past 50 years,

dental caries remains an oral health burden in the

community, in particular among preschool children

where prevalence and incidence remain high.

Although caries prevalence and severity among preschool children

declined during the first 30 years

following water fluoridation, the prevalence remains

similar and its extent/severity has been even higher

in recent decades.16 17 19 20 This suggests that there

remain some preschool children for whom the

current measures alone (water fluoridation and oral

health education) are insufficient to ensure optimal

oral health.

The dental caries prevalence and severity in

preschool children tended to rise with increasing

age.4 19 20 From the epidemiological studies, it is

thus common to find a higher percentage of caries

experience in children at the upper end of the preschool

age range. Moreover, caries experience

is not uniformly distributed within populations

of children. Children from disadvantaged and

socially marginalised populations had a higher

caries experience and severity.4 18 19 20 Preventive

measures and oral health education should start

earlier among younger children and their parents or

caregivers. In particular, efforts should focus on the

underprivileged population in our community.

The dental caries condition among Hong Kong

schoolchildren (12 years old) is relatively good by

international comparisons. Dental caries affects

60% to 90% of schoolchildren in most industrialised

countries.35 36 The current dental caries experience

in 12-year-old Hong Kong children is relatively very

low.16 17 Of note, most of the dental caries experience

was related to filled teeth, few (approximately 1

in 20) had untreated decay. This pattern can be

largely attributed to the contribution of the SDCS,

which began in the 1980s as a school-based dental

care system that effectively overcomes many social

barriers to dental care access by schoolchildren (eg

family income, education, dental health awareness).

Schoolchildren receive regular quality dental care and

treatment through the SDCS. The observed low level

of untreated dental caries among schoolchildren is in

stark contrast to findings prior to the introduction of

SDCS when most decay remained untreated or was

treated by extraction.5 6 7 8 The SDCS has also raised

awareness of oral health among schoolchildren.

Education about the importance of oral health has

likely changed children’s lifestyle and improved their

self-care practice and use of fluoride oral health care

products.

Dental attendance among primary

schoolchildren is high because of high participation

in the SDCS,37 but remains worryingly low among

secondary school and preschool children. Many

adolescents and their parents do not consider

there to be a need for such care. Less than a third

of such children reported regular attendance for

dental check-ups, presumably because this group of

children have to be seen privately to access dental

care.10 13 16 17 18 19 20 Early and regular dental check-ups to

enable preventive care should be advocated.

Conclusions

The introduction of a number of public health

measures in Hong Kong, mainly water fluoridation

and the SDCS, has improved the oral health of Hong

Kong children over the past 50 years. There has been

a decline in dental caries among schoolchildren

and adolescents. Nonetheless, the dental caries

experience has remained unchanged in recent

decades for preschool children; even a slight increase

in extent/severity has been observed. Although there

is evidence of improvement, the overall periodontal

health of Hong Kong children remains unsatisfactory.

A decrease in the prevalence and severity of enamel

defects among Hong Kong children was observed,

but there has recently been a slight increase. In view

of the limited data regarding malocclusion in Hong

Kong children, epidemiological studies should be

considered. The utilisation of dental services is low,

especially among preschool children who are not

covered by the SDCS. New policies to develop dental

care protocols to ensure evidence-based standards

of care, and to advocate regular access to dental care

and preventive services may further improve the oral

health of Hong Kong children.

References

1. Evans RW, Lo EC, Lind OP. Changes in dental health in

Hong Kong after 25 years of water fluoridation. Community

Dent Health 1987;4:383-94.

2. Chiu GK, Davies WI. The historical development of

dentistry in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J 1998;4:73-6.

3. Hong Kong Department of Health. Health Statistics.

Surveillance & Epidemiology Branch, Centre for Health

Protection. Health facts of Hong Kong. Available from:

http://www.dh.gov.hk/english/statistics/statistics_hs/files/Health_Statistics_pamphlet_E.pdf. Accessed Oct 2014.

4. Chu CH, Fung DS, Lo EC. Dental caries status of preschool

children in Hong Kong. Br Dent J 1999;187:616-20. Crossref

5. Medical and Health Department. Report on the 1st (pre-fluoridation) dental survey of school children in Hong

Kong. Medical and Health Department, Hong Kong; 1960.

6. Medical and Health Department. Report on the 2nd (post-fluoridation) dental survey of school children in Hong

Kong. Medical and Health Department, Hong Kong; 1962.

7. Wong KK. Report of a dental survey in Hong Kong 1968.

The Government Dental Service, Hong Kong and the

World Health Organization; 1968.

8. Law YH. Dental health status of primary school children

in Hong Kong. The Bulletin. Hong Kong Soc Community

Med 1981;12:1-16.

9. King NM, Ling JY, Ng BV, Wei SH. The dental caries status

and dental treatment patterns of 12-year-old children in

Hong Kong. J Dent Res 1986;65:1371-4. Crossref

10. Lind OP, Evans RW, Holmgren CJ, Corbet EF, Lim LP,

Davies WI. Hong Kong Survey of Adult Oral Health 1984.

Hong Kong: Department of Periodontology and Public Health,

Faculty of Dentistry, University of Hong Kong; 1986.

11. Wong PY. A report on a dental survey of primary school

children in Hong Kong. Medical and Health Department,

Hong Kong; 1987.

12. Lo EC, Evans RW, Lind OP. Dental caries status and

treatment needs of the permanent dentition of 6-12-year-olds

in Hong Kong. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol

1990;18:9-11. Crossref

13. Kwan EL. Oral health status of 13 and 15 year-old secondary school children in Hong Kong [dissertation]. Hong Kong: University of Hong Kong; 1992.

14. Yiu C, Wong MC, Chan M, et al. Oral health of 15-year-old

secondary school students in H.K. Hong Kong: Faculty of

Dentistry, University of Hong Kong; 2001.

15. Evans RW, Lo EC. Effects of School Dental Care Service

in Hong Kong—primary teeth. Community Dent Oral

Epidemiol 1992;20:193-5. Crossref

16. Hong Kong Department of Health. Oral health survey

2001: common dental diseases and oral health related

behaviour. Hong Kong SAR: Dental Services Head Office,

Department of Health; 2002.

17. Hong Kong Department of Health. Oral health survey

2011: common dental diseases and oral health related

behaviour. Hong Kong SAR: Dental Services Head Office,

Department of Health; 2012.

18. Wei SH, Holm AK, Tong LS, Yuen SW. Dental caries

prevalence and related factors in 5-year-old children in

Hong Kong. Pediatr Dent 1993;15:116-9.

19. Lo EC, Loo EK, Lee CK. Dental health status of Hong Kong

preschool children. Hong Kong Dent J 2009;6:6-12.

20. Chu CH, Ho PL, Lo EC. Oral health status and behaviours

of preschool children in Hong Kong. BMC Public Health

2012;12:767. Crossref

21. Ainamo J, Barmes D, Beagrie G, Cutress T, Martin J, Sardo-Infirri J. Development of the World Health Organization

(WHO) community periodontal index of treatment needs

(CPITN). Int Dent J 1982;32:281-91.

22. Wu D. Provision of outreach dental service and caries

risk assessment to preschool children in Hong Kong

[dissertation]. Hong Kong: University of Hong Kong; 2011.

23. Ainamo J, Bay I. Problems and proposals for recording

gingivitis and plaque. Int Dent J 1975;25:229-35.

24. King NM. Developmental defects of enamel in Chinese

girls and boys in Hong Kong. Adv Dent Res 1989;3:120-5.

25. Evans RW. Changes in dental fluorosis following an

adjustment to the fluoride concentration of Hong Kong’s

water supplies. Adv Dent Res 1989;3:154-60.

26. Evans RW, Stamm JW. Dental fluorosis following downward

adjustment of fluoride in drinking water. J Public Health

Dent 1991;51:91-8. Crossref

27. Wong HM, McGrath C, King NM. Diffuse opacities in

12-year-old Hong Kong children—four cross-sectional

surveys. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2014;42:61-9. Crossref

28. Wong HM, McGrath C, Lo EC, King NM. Association

between developmental defects of enamel and different

concentrations of fluoride in the public water supply.

Caries Res 2006;40:481-6. Crossref

29. Wong HM, Peng SM, Wen YF, King NM, McGrath CP. Risk

factors of developmental defects of enamel—a prospective

cohort study. PLoS One 2014;9:e109351. Crossref

30. A review of the developmental defects of enamel index

(DDE Index). Commission on Oral Health, Research &

Epidemiology. Report of an FDI Working Group. Int Dent

J 1992;42:411-26.

31. Cho SY, Ki Y, Chu V. Molar incisor hypomineralization

in Hong Kong Chinese children. Int J Paediatr Dent

2008;18:348-52. Crossref

32. Allwright WC, Burndred WH. A survey of handicapping

dentofacial anomalies among Chinese in Hong Kong. Int

Dent J 1964;14:505-19.

33. Wang G, Hägg U, Ling J. The orthodontic treatment need

and demand of Hong Kong Chinese children. Chin J Dent

Res 1999;2:84-92.

34. Brook PH, Shaw WC. The development of an index of

orthodontic treatment priority. Eur J Orthod 1989;11:309-20.

35. Petersen PE, Bourgeois D, Ogawa H, Estupinan-Day S,

Ndiaye C. The global burden of oral diseases and risks to

oral health. Bull World Health Organ 2005;83:661-9.

36. Dye BA, Tan S, Smith V, et al. Trends in oral health status:

United States, 1988-1994 and 1999-2004. Vital Health Stat

11 2007;(248):1-92.

37. King NM. Paediatric dentistry in Hong Kong. Int J Paediatr

Dent 1998;8:1-2. Crossref