Hong Kong Med J 2016 Aug;22(4):347–55 | Epub 6 Jul 2016

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj164865

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE CME

Prevalence of infections among residents of Residential Care Homes for the Elderly in Hong Kong

Carmen SM Choy, MB, BS1;

H Chen, MB, BS, FHKAM (Community Medicine)2;

Carol SW Yau, MB, BS, FHKAM (Community Medicine)3;

Enoch K Hsu, BSc, MSc2;

NY Chik, BNurs2;

Andrew TY Wong, MB, BS, FHKAM (Medicine)2

1 Accident and Emergency Department, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Jordan,

Hong Kong

2 Infection Control Branch, Centre for Health Protection, Hong Kong

3 Surveillance and Epidemiology Branch, Centre for Health Protection,

Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Carmen SM Choy (carmencly@yahoo.com.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: A point prevalence study was

conducted to study the epidemiology of common

infections among residents in Residential Care

Homes for the Elderly in Hong Kong and their

associated factors.

Methods: Residential Care Homes for the Elderly in

Hong Kong were selected by stratified single-stage

cluster random sampling. All residents aged 65 years

or above from the recruited homes were surveyed.

Infections were identified using standardised

definitions. Demographic and health information—including medical history, immunisation record,

antibiotic use, and activities of daily living (as

measured by Barthel Index)—was collected by a

survey team to determine any associated factors.

Results: Data were collected from 3857 residents

in 46 Residential Care Homes for the Elderly from

February to May 2014. A total of 105 residents had

at least one type of infection based on the survey

definition. The overall prevalence of all infections was

2.7% (95% confidence interval, 2.2%-3.4%). The three

most common infections were of the respiratory

tract (1.3%; 95% confidence interval, 0.9%-1.9%),

skin and soft tissue (0.7%; 95% confidence interval,

0.5%-1.0%), and urinary tract (0.5%; 95% confidence

interval, 0.3%-0.9%). Total dependence in activities

of daily living, as indicated by low Barthel Index score

of 0 to 20 (odds ratio=3.0; 95% confidence interval,

1.4-6.2), and presence of a wound or stoma (odds

ratio=2.7; 95% confidence interval, 1.4-4.9) were

significantly associated with presence of infection.

Conclusions: This survey provides information

about infections among residents in Residential Care

Homes for the Elderly in the territory. Local data

enable us to understand the burden of infections and

formulate targeted measures for prevention.

New knowledge added by this study

- Characteristics of local Residential Care Homes for the Elderly (RCHE) residents were explored. Most individuals had medical co-morbidities and required assistance with activities of daily living (ADL); use of an indwelling medical device was also common.

- Local prevalence of infections among residents in RCHE was 2.7% and the most common infection was of the respiratory tract.

- Total dependence in ADL and presence of a wound or stoma were associated with presence of infections among residents in RCHE in Hong Kong.

- Measures that focus on prevention of respiratory tract infection among the elderly should be emphasised and an infection control programme should be designed to enhance such practice in RCHE.

- Infection control protocols can be developed according to specific areas of nursing care, for example, wound care or catheter care.

Introduction

Ageing is a worldwide phenomenon, and Hong

Kong, without exception, is encountering the same

population change. In 2014, the proportion of our

elderly population aged 65 years or above was 15%.

This proportion is expected to double over the next

20 years, to 28% in 2034.1

In Hong Kong, Residential Care Homes for

the Elderly (RCHEs) provide different levels of care

for the elderly who—for personal, social, health, or

other reasons—can no longer live alone or with their

family. These RCHEs can be broadly categorised as

private homes (PH) and non-private homes (NPH);

the former are run by private entrepreneurs and

vary in size and capacity, while the latter are run by

non-governmental organisations and include care

and attention homes for the elderly and subvented,

and self-financing and contract homes that provide

subsidised care for the elderly. In 2015, there were

around 740 RCHEs providing over 73 000 residential

placements over the territories and residential care

for approximately 7% of the elderly in Hong Kong.1 2

These numbers are expected to increase further.

Generally speaking, RCHEs are very

heterogeneous in terms of size, facilities, manpower,

and level of care. Some residents are encouraged

to participate in various types of group activities

while some residents may require assistance in daily

activities. These activities, together with the confined

and shared living environment, may promote the

transmission of infectious diseases.

Infections are an important cause of morbidity

and mortality among the elderly, and place a

significant burden on our health care system.

Residents of RCHEs are usually frail; compared

with their community-dwelling counterparts,

they are more susceptible to infections and related

complications. Overseas studies conducted in a

hospital setting have shown that the mortality rate

of community-acquired pneumonia is 30%, while

that in nursing homes is substantially higher, with a

reported rate of up to 57%.3 Infections may be a cause

as well as the consequence of functional impairment

among RCHE residents, leading to a reduction in

their quality of life.4

Local studies of infectious diseases in the RCHE

setting are scarce. The last such survey was conducted

in 2006.5 Continuous or regular surveillance serves

to reveal the disease burden to increase awareness of

infections and to identify critical areas for infection

control. It is important that we understand the

local epidemiology and burden of infections among

RCHE residents and apply measures to control these

infections and safeguard the health of this vulnerable

group.

Methods

We conducted a point prevalence survey of common

infections among residents of RCHEs in Hong Kong.

Population and setting

All RCHEs in Hong Kong were included. All residents

aged 65 years or above who were present at 9 am (the

reference time) on the survey day were included.

Residents were excluded from the survey if: (1) he/she was not present at the reference time (owing

to medical appointment, admission to hospital, or

home leave from the RCHE); or (2) he/she attended

the RCHE as a day patient/resident.

Sampling strategy

A list of all RCHEs in Hong Kong was retrieved from

the Social Welfare Department website.6 All RCHEs

on the list were stratified according to the main

geographical region of Hong Kong (Kowloon, Hong

Kong Island, and New Territories) and type of RCHE

(PH and NPH) into six strata. Stratified single-stage

cluster random sampling was performed using the

captioned list as the sampling frame. All residents

were surveyed in each recruited home.

Data collection

The survey was conducted from February to May

2014. A survey team comprising doctors, nurses,

and research staff visited the RCHEs for data

collection on any one day during the survey period.

A standardised survey form was developed based on

a previous similar prevalence survey.5 This survey

form comprised four parts: (1) socio-demographic

information about the resident; (2) health information

including medical history, vaccination history, and

antibiotic use; (3) measurement of activities of daily

living (ADL) using the Barthel Index (BI)7; and (4) a

checklist of acute symptoms of common infections.

Symptoms of acute infections were obtained by

doctors by interviewing the residents or their major

carers with the help of RCHE staff. All health-related

information was verified by doctors or nurses;

functional status of residents was assessed by trained

nurses using the BI.

A pilot study was conducted in two RCHEs in

February 2014 to field test the data collection tools.

Inter-rater reliability on BI was assessed during the

period for the six trained nurses. Cohen’s kappa of

BI estimated ranged from 0.8 to 1, suggesting good

inter-rater reliability among them.

The survey was conducted in an anonymous

manner. Written consent was obtained from the

RCHEs. Verbal consent was obtained from residents

and/or their relatives. If any residents (or their

relatives) refused to participate in the survey, their

information was not retrieved. If relevant data

were not available on the survey day, data would be

retrieved within 1 week. The study was approved by

the Ethics Committee of the Department of Health.

Outcome measures

Infection was defined using any one of the following

criteria: (1) presence of symptoms and/or signs of

infection that developed in the 24 hours preceding

the survey day, that fulfilled the surveillance criteria

of the Canadian Consensus Conference8; (2)

infection diagnosed by a locally registered physician

(eg visiting medical officers, general practitioners);

or (3) consumption of antimicrobial agents on the

survey day for a specific infection.

Sample size and power estimation

Sample size was estimated to determine the

prevalence of infections among residents in RCHEs

in Hong Kong. Based on a previous prevalence

survey in Hong Kong,5 the prevalence of infections

was 5.7%, the design effect (DEFF) was 1.765 with an

intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.025 and

average cluster size of 31.61. Assuming the margin of

error to be 0.2, given a conservative DEFF of 2, the

sample size calculated was 3178.

Statistical analyses

R (version 3.0.2) was used for statistical analysis.

“Survey” package (version 3.29-5) in R was used

to calculate the prevalence of infections adjusted

for cluster sampling. Prevalence rates of infections

and other study variables were calculated using

“svyciprop” function from the “Survey” package.

Logistic regression with adjustment on cluster

sampling was performed using “svyglm” function

from the “Survey” package to identify risk factors for

infection. Variables were included for multivariate

analysis if: (1) the P value was <0.25 in univariate

analysis or (2) the variables had been considered

as risk factors of infection in previous studies,

such as mobility status, use of medical devices,

presence of wound, home size, gender, and recipient

of the Comprehensive Social Security Assistance

(as a surrogate measurement of social economic

status).9 10 11 12 In addition, subgroup analyses were

performed to explore the association of specific risk

factors with different types of infection, such as the

presence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

(COPD) with respiratory tract infection (RTI) and

diabetes mellitus (DM) with skin and soft tissue

infection (SSTI). In order to adjust for multiple

comparisons, P values calculated for exploration

of association between risk factors and different

types of infection were adjusted using Bonferroni

correction. A P value of <0.05 was considered to be

statistically significant.

Results

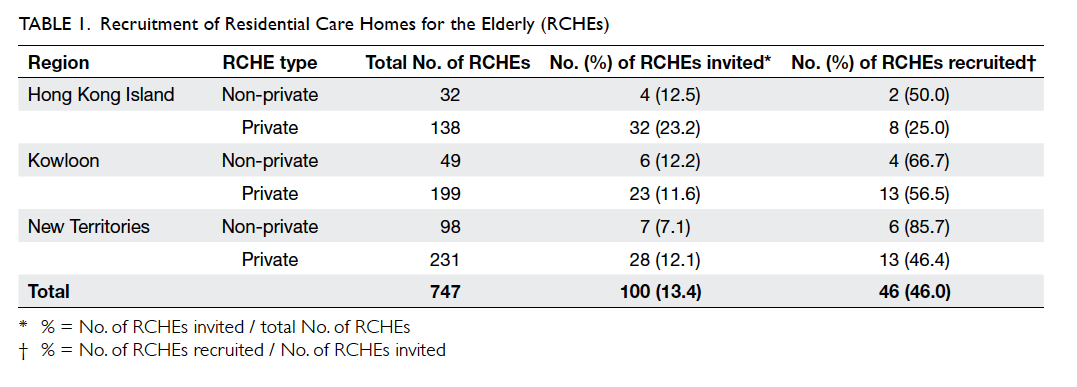

A total of 100 RCHEs were invited. The overall

response rate was 46% (n=46). Table 1 illustrates the number of recruited RCHEs stratified by region

and home type. A higher response rate was noted in

NPHs (70.6%, n=12) than PHs (42.2%, n=35). The

ICC and DEFF calculated from the sample collected

were 0.0035 and 1.45, respectively. The mean

home capacity of the participating RCHEs was 111

residents per home (95% confidence interval [CI],

88-133 residents per home) with a median occupancy of 89%. Among the

staff in participating RCHEs, 45.9% were personal

care workers, 14.7% were health care workers, and

11% were nurses (including registered nurses and

enrolled nurses). There was no significant difference

in terms of home capacity, occupancy, or staffing

level between participating and non-participating

RCHEs based on data from the annual assessment

of all RCHEs conducted by Elderly Health Service,

Department of Health.

Demographics and underlying co-morbidity of residents

Among the 4127 residents in the participating

RCHEs, 261 (6.3%) were excluded from the survey as

they were not available due to hospitalisation, medical

appointment, home leave, or other personal reasons.

All 3866 residents who were at the participating

RCHEs at 9 am on the survey day were invited and

joined the survey. Nine (0.2%) residents were not

included in the analysis as their RCHEs failed to

provide relevant information subsequently. Among

the 3857 residents surveyed, the mean age was 85.2

years, and the female-to-male ratio was 1.9:1. Most

residents were Chinese (99.8%, n=3849), and 56.5%

(n=2178) of those surveyed were above 84 years

old. The mean age of male and female residents was

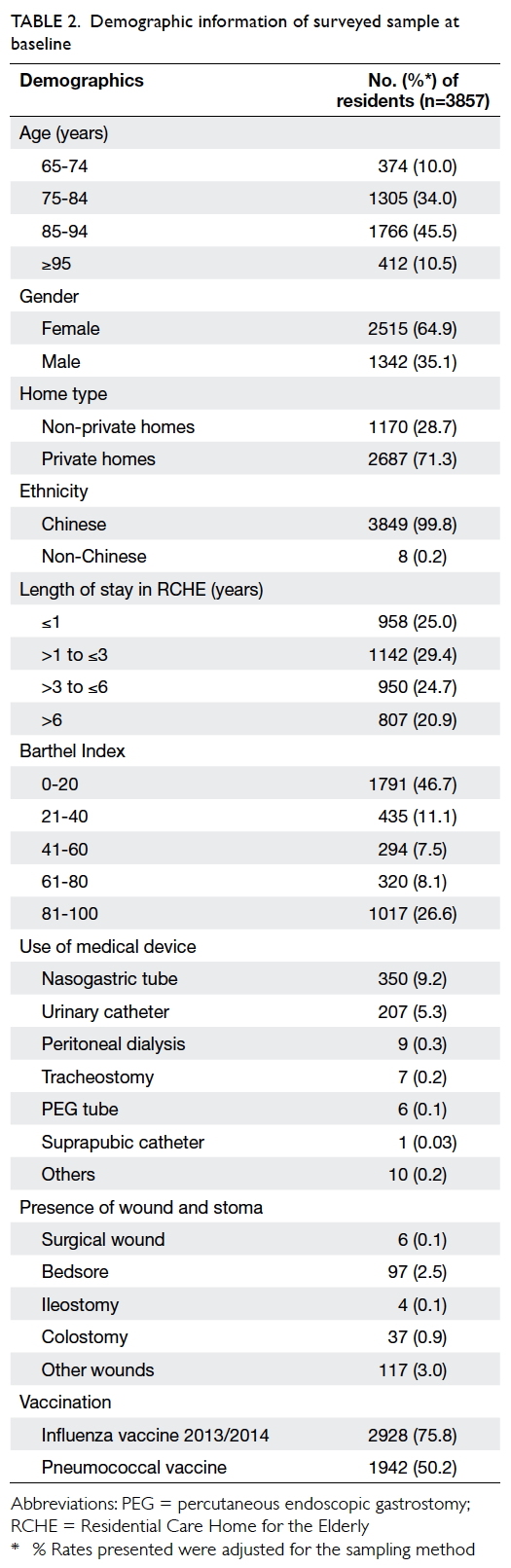

82.4 and 86.8 years, respectively. Table 2 shows the

demographic information of the surveyed sample.

Duration of their stay in RCHEs varied; a quarter had

resided in a RCHE for less than 1 year, 29.4% for 1 to 3

years, 24.7% for 3 to 6 years, and 20.9% for more than

6 years. For ADL of residents, the median BI score

was 30, and 46.7% of residents scored 0-20 indicating

they were totally dependent in ADL.13 Regarding use

of an indwelling medical device, 14.4% of residents

required at least one device, mostly a nasogastric

tube (9.2%) or urinary catheter (5.3%). Up to 75.8% of

residents received the 2013/2014 seasonal influenza

vaccine and 50.2% had received the pneumococcal

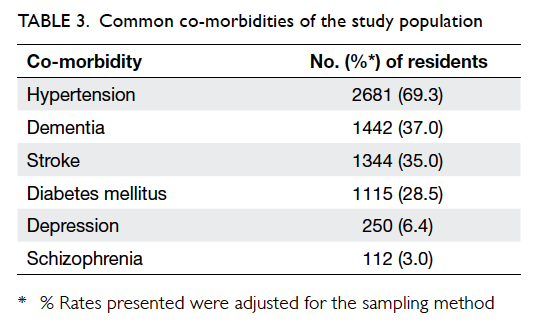

vaccine. Most residents (87.1%) had more than one

underlying co-morbidity with the most common

diagnosis being hypertension (69.3%), followed by

dementia (37.0%) and stroke (35.0%) [Table 3].

Prevalence of infections

A total of 105 residents were diagnosed with at least

one infection based on the survey definition. Among

these residents, 102 had one type of infection

and three had two types of infection. The overall

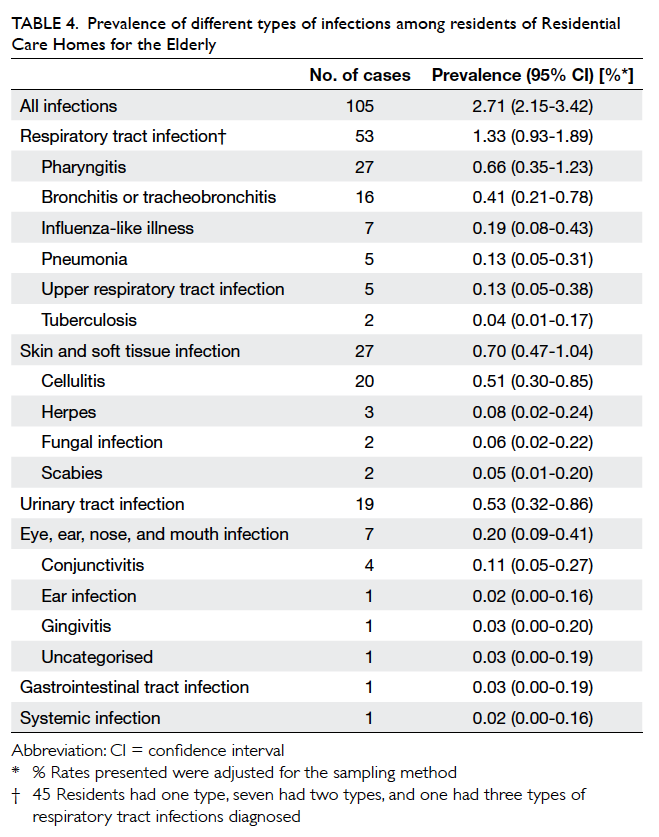

prevalence of infections was 2.7% (95% CI, 2.2%-3.4%). Table 4 shows the prevalence of different infections.

Table 4. Prevalence of different types of infections among residents of Residential Care Homes for the Elderly

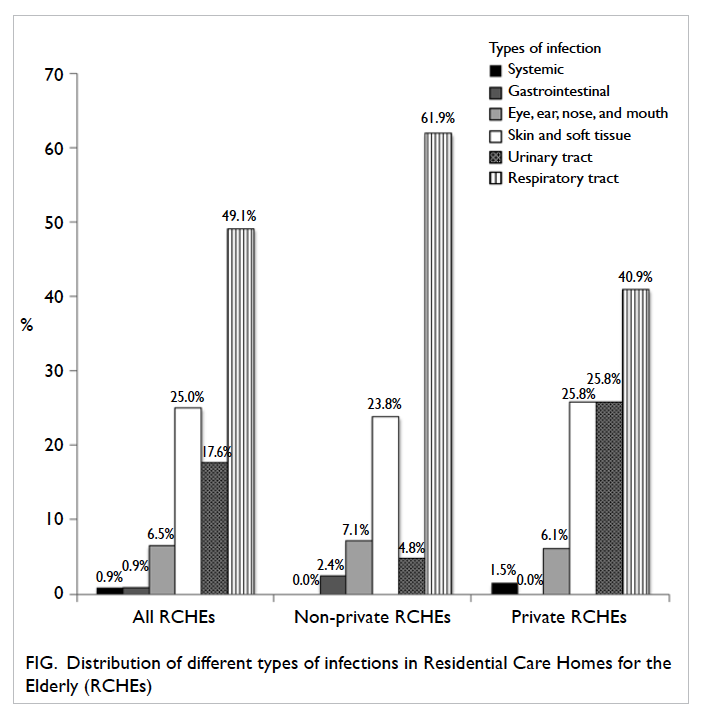

Of all the infections, RTI was the most common

type, comprising 49.1% (n=53) of all infections,

followed by SSTI (25.0%, n=27) and urinary tract

infection (UTI) [17.6%, n=19; Fig].

Figure. Distribution of different types of infections in Residential Care Homes for the Elderly (RCHEs)

Factors associated with infectious diseases

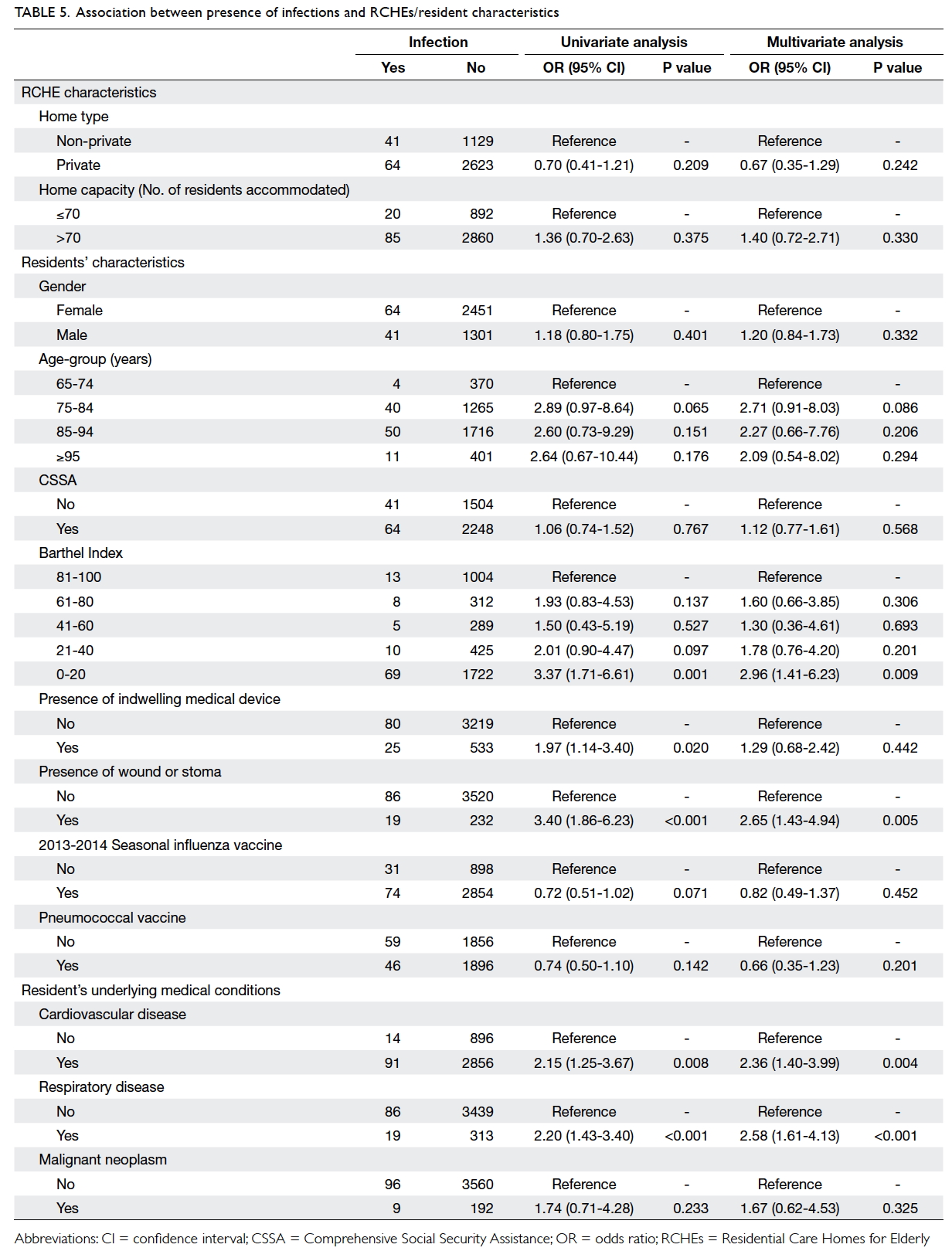

Table 5 illustrates factors associated with presence of

any infection and specific infections. Residents with

ADL dependency, as reflected by low BI score of

0-20 (odds ratio [OR]=3.0; 95% CI, 1.4-6.2), presence

of a wound or stoma (OR=2.7; 95% CI, 1.4-4.9), or

co-morbidities including cardiovascular diseases

(CVD) [OR=2.4; 95% CI, 1.4-4.0] and respiratory

diseases (OR=2.6; 95% CI, 1.6-4.1) were significantly

likely to have an infection. Seasonal influenza

vaccination (OR=0.82; P=0.452) and pneumococcal

vaccination (OR=0.66; P=0.201) were associated

with a lower risk of infection but neither reached

statistical significance.

Subgroup analysis by site of infection showed

that low BI score (OR=2.6; 95% CI, 1.3-5.2) and COPD (OR=3.7; 95%

CI, 1.5-9.1) were significantly associated with RTI. Factors significantly associated with

SSTI included low BI score (OR=5.5; 95% CI, 1.7-17.5), presence of wound(s) and stoma (OR=9.0;

95% CI, 4.7-17.1), having DM (OR=1.9; 95% CI,

1.0-3.6), mental illness (OR=3.7; 95% CI, 1.2-11.8),

and CVD (OR=4.6; 95% CI, 1.3-16.3). Presence of

a urinary catheter was significantly associated with

UTI (OR=5.6; 95% CI, 1.9-16.2).

Discussion

This point prevalence survey aimed to investigate

the prevalence of infections among residents

living in RCHEs in Hong Kong. It is essential to

understand that this specific group of elderly

differs significantly from their community-dwelling

counterparts in terms of health condition, level of

mobility, daily routine behaviour, and level of care

received. The confined living environment, shared

bathing equipment, group dining facilities, and close

human-to-human contact potentially foster the

transmission of infection. A local study has shown

that nursing home residency is an independent

predictor of infection-related mortality, pneumonia-related

mortality, and all-cause mortality.14

In this study, the overall prevalence of infections

was 2.7%. Among all infections, RTI, SSTI, and UTI

ranked top with a prevalence of 1.3%, 0.7%, and

0.5%, respectively. Low BI score of 0-20, presence

of a wound or stoma, and co-morbidities including

CVD and respiratory diseases were significantly

associated with presence of infection.

Compared with the previous prevalence

survey of infections among residents of RCHEs in

Hong Kong conducted in November 2006,5 a lower

overall prevalence was noticed in this survey. In

2006 the prevalence was 5.7%.5 A similar pattern of

prevalence regarding type of infection was observed

for common cold or pharyngitis (included under RTI

in our study) that was the most common type of

infection, followed by SSTI and UTI. This reduction

in overall prevalence over a 6-year period may be due

to a better awareness of infection control among the

general public and health care workers, particularly

after the severe acute respiratory syndrome endemic

in 2003 and H1N1 swine influenza endemic in 2009.

Another encouraging finding in this study may also

account for this improved trend: an increased uptake

of seasonal influenza vaccine was noted, from 60.3%

in year 2012-2013 to 75.8% in year 2013-2014 among

surveyed residents.

Prevalence surveys conducted in long-term

care facilities (LTCF) overseas have generally

reported an overall higher prevalence of infection,

from 3.4% to 11.8%.15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 Most reported UTI as the most common type of infection.15 16 19 20 21 22 23 Despite a lower prevalence in our survey compared with

overseas surveys, we must interpret the results with

caution for a few reasons. First, the difference in

survey method, study population, and case definition

among these studies may render direct comparison

of prevalence inappropriate. Second, it is important

to understand the differences between settings and

the elderly population in LTCF in Hong Kong and

those overseas. In the US, LTCF can further be

categorised into veteran care centres that provide

care for elderly military officers, and nursing homes

and residential care communities that offer different

levels of assistance in ADL depending on the elderly

individual’s capacity for self-care.25 On the contrary,

in Europe, more than two thirds of those receiving

institutional care are above 80 years of age.26 Third,

staff levels, occupancy,25 local infection practice and

guidelines, and accessibility to health care facilities,

such as emergency room or secondary health care

facilities in overseas LTCF differ significantly from

our local setting. These factors may explain the

difference in prevalence between local RCHEs and

overseas LTCF.

This study also investigated the risk factors

associated with the presence of infection among

residents. Low BI score of 0-20 representing total

dependency in ADL, and presence of a wound

or stoma were associated with presence of any

type of infection. The findings are consistent with

past studies that suggest limitations in ADL or

functional impairment, and presence of skin ulcers

are risk factors for infection.15 17 21 Nevertheless, the

protective effect of immunisation with seasonal

influenza vaccine and pneumococcal vaccine was

not clearly demonstrated in this study.

Regarding RTI, which essentially includes upper tract infections (eg common cold or influenza-like illness) and lower tract infections (eg pneumonia), COPD and lower BI score of 0-20

were two associated factors. A few previous studies

that focused on risk factors for pneumonia (or

specifically nursing home–associated pneumonia)

also suggested that a low BI score,27 low ADL score,27

profound debility (measured by Karnofsky score of

≤40),28 and COPD5 28 are associated factors, and is

compatible with our findings.

Although multiple factors were significantly

associated with SSTI in our study, including low BI

score, presence of wounds and stoma, co-morbidities

like DM, mental illnesses and CVD, limited studies

have determined risk factors for SSTI in LTCF. In

Cotter et al’s study,16 presence of a urinary catheter,

vascular catheter, pressure sores, or other wounds

was significantly associated with SSTI. It is possible

that individuals with DM or CVD are more prone to

development of an ulcer or poor wound healing, and

thus have a higher risk of SSTI. Further studies may

be necessary to delineate the association between

SSTI and other co-morbidities.

Presence of an indwelling urinary catheter

is not surprisingly associated with UTI, and is

compatible with the previous local study5 and most

overseas studies.16 29 30 This reflects the importance

of proper care for indwelling urinary catheters in

RCHEs.

Our study provides more information

regarding prevalence and risk factors associated

with infectious diseases in RCHEs in Hong Kong.

Readers, however, must take note of a few limitations

of this study.

First, a point prevalence study offers only a

snapshot of events and thus a causal relationship

between risk factors and infections cannot be

established. Our study was conducted during

February to May, which was late winter to early

spring time in Hong Kong, and the prevalence of

different infections may have a seasonal variation,

for example, influenza.31 32 Comparison needs to take account of the season during which the study was

conducted.

Second, only 46 of the 100 invited RCHEs

participated in the survey. This response rate may

affect the generalisability of results. It is possible that

the RCHEs with stronger compliance with infection

control measures volunteered to participate whilst

those homes that refused were less compliant and

had a higher infection prevalence.

Third, the exclusion of residents who were not

present at the RCHEs at the reference time may have

led to underestimation of the prevalence of infection.

We reviewed the list of residents excluded from the

survey and found 18 of them had been admitted to

hospital in the 2 days preceding the survey, of whom

10 were admitted because of symptoms or signs

suggestive of infection. Assuming they all fulfilled

the criteria for infection in this survey, the effect

was likely minimal, with an adjusted prevalence of

infections of 2.9% (95% CI, 2.3%-3.7%).

Fourth, demographic data, medical history,

and vaccination history were retrieved from records

maintained by RCHEs, but different RCHEs had

different practices of record keeping. Data may have

been incomplete or inadequate in certain RCHEs

while others may have provided more detailed data.

These differences were minimised by a standard

protocol and training of the survey team and

verification of data with RCHE staff on site.

Finally, we did not include any infection control

practice measures in our study, such as hand hygiene

compliance of staff and environmental hygiene

measures. While the aim of the study was not to

assess the infection control practices of RCHEs,

these factors could potentially affect the results in

the risk factor analysis, and hence, readers should

interpret the regression result in the context that

confounding may present.

Conclusions

The overall prevalence of infections among RCHE

residents was estimated to be 2.7%. Associated

factors were identified. It is recommended that

infection control measures be targeted towards

these factors. Training for RCHE staff and a policy

to execute infection control guidelines in RCHEs

should be planned early in view of an increasing

demand for services provided by RCHEs. Further

study can be carried out at different times of the

year to identify any seasonal changes and pattern

of infections, or targeted at residents admitted to

public hospitals with acute infections to estimate the

overall burden on our health care sector.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the survey team

for their hard work in study design and fieldwork.

Furthermore, we extend our heartfelt gratitude to

all the participating RCHEs and their staff for their

assistance throughout the study. Without their

support, this survey would not have been possible.

The authors would like to thank the Elderly Health

Service, Department of Health for sharing their data

on annual assessment of RCHEs.

Declaration

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Census and Statistics Department, Hong Kong SAR

Government. Hong Kong population projections 2015-2064. September 2015. Available from: http://www.statistics.gov.hk/pub/B1120015062015XXXXB0100.pdf.

Accessed 22 Dec 2015.

2. Social Welfare Department, Hong Kong SAR Government.

Provision of residential care services for elders (non-governmental organisations versus private sector). March 2015. Available from:

http://www.swd.gov.hk/doc/elderly/ERCS/Overview%20item(b)English(31-3-2015).pdf. Accessed 22 Dec 2015.

3. Gavazzi G, Krause KH. Ageing and infection. Lancet Infect

Dis 2002;2:659-66. Crossref

4. Büla CJ, Ghilardi G, Wietlisbach V, Petignat C, Francioli

P. Infections and functional impairment in nursing home

residents: a reciprocal relationship. J Am Geriatr Soc

2004;52:700-6. Crossref

5. Chen H, Chiu AP, Lam PS, et al. Prevalence of infections in

residential care homes for the elderly in Hong Kong. Hong

Kong Med J 2008;14:444-50.

6. Social Welfare Department, Hong Kong SAR Government.

List, licences and briefs of residential care homes.

Available from: http://www.swd.gov.hk/en/index/site_pubsvc/page_elderly/sub_residentia/id_listofresi/.

Accessed 31 Dec 2013.

7. Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: The

Barthel Index. Md State Med J 1965;14:61-5.

8. McGeer A, Campbell B, Emori TG, et al. Definitions of

infection for surveillance in long-term care facilities. Am

J Infect Control 1991;19:1-7. Crossref

9. Magaziner J, Tenney JH, DeForge B, Hebel JR, Muncie HL

Jr, Warren JW. Prevalence and characteristics of nursing

home–acquired infections in the aged. J Am Geriatr Soc

1991;39:1071-8. Crossref

10. Li J, Birkhead GS, Strogatz DS, Coles FB. Impact of

institution size, staffing patterns, and infection control

practices on communicable disease outbreaks in New York

State nursing homes. Am J Epidemiol 1996;143:1042-9. Crossref

11. Cohen S. Social status and susceptibility to respiratory

infections. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1999;896:246-53. Crossref

12. Harrington RD, Hooton TM. Urinary tract infection risk

factors and gender. J Gend Specif Med 2000;3:27-34.

13. McDowell I. Measuring health: a guide to rating scales and

questionnaires. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006. Crossref

14. Chan TC, Hung IF, Cheng VC, et al. Is nursing home

residence an independent risk factor of mortality in

Chinese older adults? J Am Geriatr Soc 2013;61:1430-2. Crossref

15. Chami K, Gavazzi G, Carrat F, et al. Burden of infections

among 44,869 elderly in nursing homes: a cross-sectional

cluster nationwide survey. J Hosp Infect 2011;79:254-9. Crossref

16. Cotter M, Donlon S, Roche F, Byrne H, Fitzpatrick F.

Healthcare-associated infection in Irish long-term care

facilities: results from the First National Prevalence Study.

J Hosp Infect 2012;80:212-6. Crossref

17. Eriksen HM, Iversen BG, Aavitsland P. Prevalence of

nosocomial infections and use of antibiotics in long-term

care facilities in Norway, 2002 and 2003. J Hosp Infect

2004;57:316-20. Crossref

18. Moro ML, Mongardi M, Marchi M, Taroni F. Prevalence

of long-term care acquired infections in nursing and

residential homes in the Emilia-Romagna Region. Infection

2007;35:250-5. Crossref

19. Lim CJ, McLellan SC, Cheng AC, et al. Surveillance of

infection burden in residential aged care facilities. Med J

Aust 2012;196:327-31. Crossref

20. Tsan L, Langberg R, Davis C, et al. Nursing home–associated

infections in Department of Veterans Affairs community

living centers. Am J Infect Control 2010;38:461-6. Crossref

21. Tsan L, Davis C, Langberg R, et al. Prevalence of nursing

home–associated infections in the Department of Veterans

Affairs nursing home care units. Am J Infect Control

2008;36:173-9. Crossref

22. Marchi M, Grilli E, Mongardi M, Bedosti C, Nobilio L,

Moro ML. Prevalence of infections in long-term care

facilities: how to read it? Infection 2012;40:493-500. Crossref

23. Dwyer LL, Harris-Kojetin LD, Valverde RH, et al. Infections

in long-term care populations in the United States. J Am

Geriatr Soc 2013;61:342-9. Crossref

24. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control.

Point prevalence survey of healthcare-associated

infections and antimicrobial use in European long-term

care facilities. May-September 2010. Available from:

http://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications/_layouts/forms/Publication_DispForm.aspx?List=4f55ad51-4aed-4d32-b960-af70113dbb90&ID=1086. Accessed 31 Dec

2013.

25. Harris-Kojetin L, Sengupta M, Park-Lee E, Valverde

R. Long-term care services in the United States: 2013

overview. Vital Health Stat 3 2013;(37):1-107.

26. Rodrigues R, Huber M, Lamura G, editors. Facts and figures

on healthy ageing and long-term care. European Centre for

Social Welfare Policy and Research; 2012. Available from:

http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.303.1022&rep=rep1&type=pdf. Accessed 22 Jan 2016.

27. Wójkowska-Mach J, Gryglewska B, Romaniszyn D, et

al. Age and other risk factors of pneumonia among

residents of Polish long-term care facilities. Int J Infect Dis

2013;17:e37-43. Crossref

28. Muder RR. Pneumonia in residents of long-term care

facilities: epidemiology, etiology, management, and prevention. Am J Med 1998;105:319-30. Crossref

29. Michel JP, Lesourd B, Conne P, Richard D, Rapin CH.

Prevalence of infections and their risk factors in geriatric

institutions: a one-day multicentre survey. Bull World

Health Organ 1991;69:35-41.

30. Eriksen HM, Koch AM, Elstrøm P, Nilsen RM, Harthug

S, Aavitsland P. Healthcare-associated infection among

residents of long-term care facilities: a cohort and nested

case-control study. J Hosp Infect 2007;65:334-40. Crossref

31. Saha S, Chadha M, Al Mamun A, et al. Influenza seasonality

and vaccination timing in tropical and subtropical areas of

southern and south-eastern Asia. Bull World Health Organ

2014;92:318-30. Crossref

32. Yang L, Wong CM, Lau EH, Chan KP, Ou CQ, Peiris JS.

Synchrony of clinical and laboratory surveillance for

influenza in Hong Kong. PLoS One 2008;3:e1399. Crossref