Hong Kong Med J 2016 Aug;22(4):341–6 | Epub 17 Jun 2016

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj154762

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Breast pain in lactating mothers

Sophie SF Leung, FHKCPaed, FHKAM (Paediatrics)

Department of Paediatrics, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong (c/o: Room 1502, 15/F, Hong Kong Pacific Centre, 28 Hankow Road, Tsimshatsui, Hong Kong)

Corresponding author: Dr Sophie SF Leung (dr.leung@ssfl.com.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: The number of new mothers who

breastfeed has increased dramatically over the last

three decades. There is a concern that the present

related medical service may be inadequate. Breast

pain is the most common complaint among lactating

mothers who seek medical help. This study aimed to

investigate this problem.

Methods: Medical records of women who

presented with breast pain to a private clinic run

by a doctor who was trained as an International

Lactation Consultant were reviewed over a period

of 6 months in 2015. Most patients were self-referred

after chatting online. Assessment included

characteristics and duration of pain, treatment prior

to consultation, feeding practices, mother’s diet,

and breast examination. Any site of blockage was

identified and relieved. Those with persistent pain

were given antibiotics. When there were signs of

abscess or abscess that could not be drained, they

were referred to a breast surgeon.

Results: A total of 69 patients were seen of whom 45

had been breastfeeding for more than 1 month. Pain

was experienced for longer than 7 days in 22 women.

Antifungal or antibacterial treatment had been

unsuccessful in 31 women prior to consultation. The

diagnoses were engorgement in five women, blocked duct in 35,

mastitis in 13, breast abscess in six, poor positioning

and latch in seven, nipple cracks in two, and skin infection

in one. Oral antibiotics were prescribed to 21 patients

and local antifungal treatment was given to one

patient only.

Conclusion: Blocked duct was the most common

cause of breast pain in lactating mothers. Without

prompt relief it is possible that it will progress

to mastitis/breast abscess or the mother may

discontinue breastfeeding. This may be a suitable

time for Hong Kong to set up one or more public full-time

breastfeeding clinics to provide a better service

to lactating mothers and to facilitate professional

training and research.

New knowledge added by this study

- Most breast pain in lactating mothers is not necessarily due to bacterial or fungal infection but due to duct blockage that can be relieved promptly by gentle breast massage and milk expression.

- Local mothers had a specific dietary practice to encourage milk production that could sometimes be harmful.

- To cope with the increased prevalence of breastfeeding, relevant clinical services should be established, including one or more full-time breastfeeding clinics in the public sector that mothers can attend without the need for medical referral. This will also help in research since local practices and clinical problems may differ to those described in the literature.

Introduction

Hong Kong has experienced a tremendous change in

lifestyle and the consequent clinical problems pose a

challenge to the medical profession. A good example

of this is infant feeding. Almost half a century ago,

the prevalence of breastfeeding in Hong Kong was

at its lowest rate of 5% in 1978 after a dramatic fall

from 44% in 1967.1 Following the joint efforts of

doctors, nurses and mothers, the prevalence of the

ever breastfeeding rate in Hong Kong has rapidly

climbed from 20% in 1992 to 60% in 2002 and 86%

in 2014.2 The efforts of both the UNICEF Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative and the Department of Health should be applauded.

Breast milk is the best for babies. Mothers

should be encouraged to breastfeed fully for 6

months, followed by introduction of solid foods and

continuation of breastfeeding for 2 years or more.

Recent data have shown that only 27% of mothers

can sustain breastfeeding for 4 to 6 months.2 There

are areas where we, as medical professionals, can

provide support. For historical reasons, however, not

many local doctors and nurses have been trained to

manage the clinical problems encountered by breastfeeding mothers. One such problem is breast pain.

Breast pain, which may lead to cessation

of breastfeeding, is the most common complaint

of lactating mothers seen in a private general

paediatric clinic run by a doctor (author) trained in

2000 as an International Lactation Consultant. This

study aimed to analyse the reasons for breast pain

and how it can be relieved.

Methods

Clinical records of lactating

mothers who presented with breast pain over a

6-month period (January to June 2015) were retrieved. Patients

were self-referred after chatting online with other

breastfeeding mothers. During consultation,

patients were asked about the history of pain,

prior treatment, breastfeeding practices, and their

own diet. Breast examination was then performed,

including the nipple and areola, to identify any

redness or tenderness. In particular, any blockage

was identified.

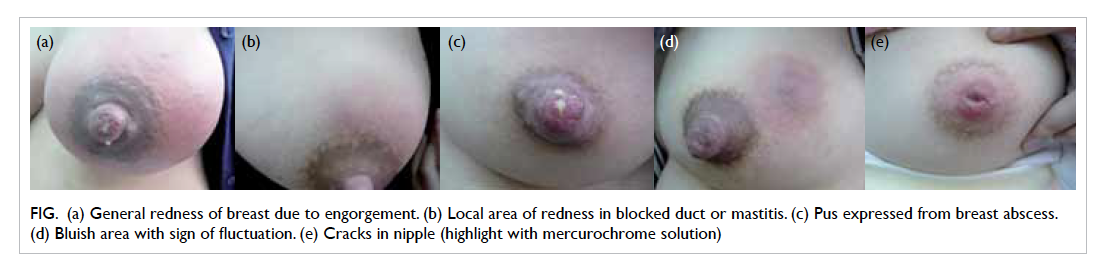

If redness or tenderness was generalised

in either or both breasts, it was diagnosed as

engorgement (Fig a). If it was confined to a segment, this implied only a lobule was involved. If gentle

massage and milk expression provided relief, a

blocked duct was diagnosed (Fig b). The ability to express pus (Fig c) or an area of fluctuation or skin thinning (Fig d) was indicative of breast abscess.

Mastitis was diagnosed in the presence of fever

and tenderness/mass that could not be relieved but

had not progressed to an abscess.3 Nipples were

examined for cracks (Fig e). Feeding position and

latch were checked when appropriate and corrected

accordingly. When there was a white spot in the

nipple, it was cleared by simple expression or by

using a needle to open up the blockage. If there was

a shinny reddish colour of the nipple and areola

together with burning, stinging, and itchiness then

fungal infection was diagnosed. In such case, the

baby’s mouth was also examined for the presence of

oral thrush.

Figure. (a) General redness of breast due to engorgement. (b) Local area of redness in blocked duct or mastitis. (c) Pus expressed from breast abscess. (d) Bluish area with sign of fluctuation. (e) Cracks in nipple (highlight with mercurochrome solution)

Results

A total of 69 patients were seen of whom 45 had been

breastfeeding for more than 1 month. All except six

were in their 30s. The age of the baby was less than

1 month in 24 (35%) women, 1 to 6 months in 27

(39%), and over 6 months in 18 (26%). Only 13 (19%)

used complementary infant milk formula.

Breast pain was present for less than 3 days in

35 (51%) women but for longer in the remaining 34

(49%). Pain duration exceeded 7 days in 22 (32%); 15

(22%) of whom had intermittent pain for 14 to 30

days. In 31 (45%) patients, earlier treatment had been

received from various sources including Maternal

and Child Health Centres (MCHCs), family doctors,

general practitioners, obstetricians, doctors at an

accident and emergency department, surgeons in

a breast surgery clinic, or lactation consultants.

Antifungal or antibacterial medication, either local

or systemic, was prescribed.

Apart from breast pain, there were other

additional complaints: nipple pain in eight (12%) women,

sharp needle pain after feeding in eight (12%), white

spot at nipple in 15 (22%), and fever in 14 (20%).

All had decreased milk production by the affected

breast despite frequent feeding or pumping.

The following diagnoses were made: nipple

cracks (n=2), poor positioning and latch (n=7),

engorgement (n=5), blocked duct (n=35), mastitis

(n=13), breast abscess (n=6), and skin infection

(n=1). One had all pus drained via the milk duct.

Another had pus formed in the sebaceous gland at

the areola and was fully drained. The remaining four

were referred to a surgeon for further management.

Oral antibiotics were prescribed to 21 (30%) women. Fungal

infection was suspected in only one woman. Clinical

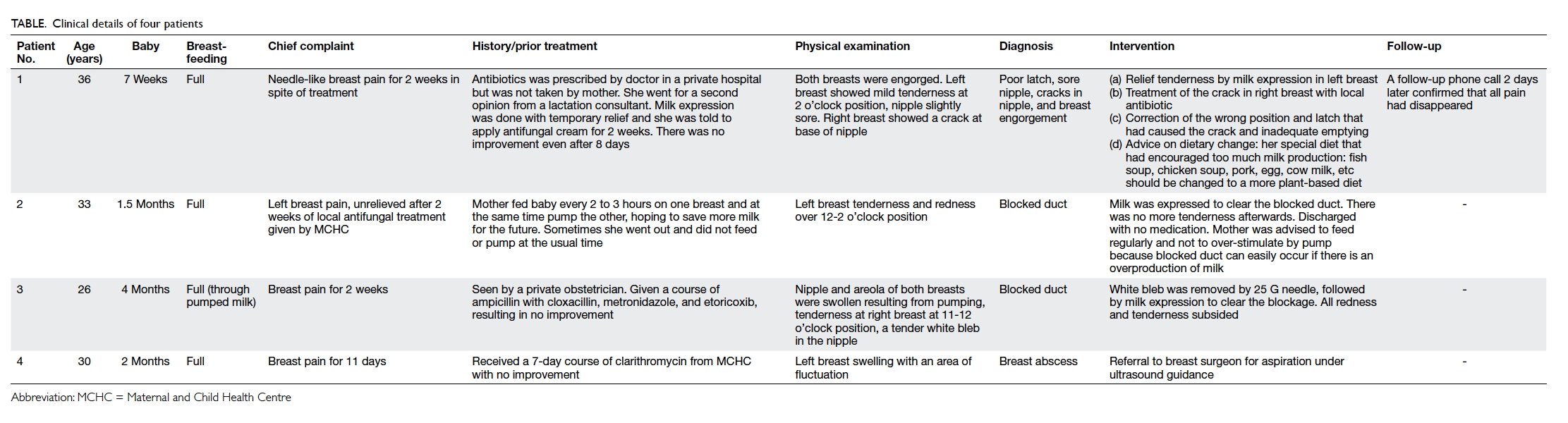

details of four patients chosen for illustration are

shown in the Table.

Discussion

Subjects in this study represent mothers who were

very dedicated to breastfeeding. Most had been

breastfeeding for more than 1 month and had not

given up, despite experiencing pain for quite a

number of days.

Blocked duct/mastitis

Blocked duct was the most common cause of breast

pain in this study group. Delay in diagnosing and

treating a blocked duct can lead to a more serious

condition of mastitis and breast abscess.

Engorgement, blocked duct, mastitis, and

breast abscess reflect progression from a common

original problem of inadequate drainage that can

be due to poor positioning and latching, inadequate

emptying, or overproduction.3 Obtaining a good

history, performing a thorough breast examination,

and milk expression can help to make the diagnosis.

Engorgement usually involves the whole

breast whereas a blocked duct involves a lobule.

In the latter, redness and tenderness are apparent

and examination of the areola may reveal a tender

swelling representing a blockage of the duct near the

opening. Gentle massage and milk expression will

relieve the pain and tenderness. A simple blocked

duct can be relieved immediately. Nonetheless, when

the swelling can only be partially relieved, it may

represent tissue inflammation indicative of mastitis.

Mothers were encouraged to feed more often on the

affected breast. If this failed after one or two feeds,

antibiotics were prescribed to prevent progression

to breast abscess.

Milk is a very good medium for bacterial

culture. Stasis of milk for too long may lead to

infection (mastitis) and pus formation (abscess). The

common guideline is to relieve a blocked duct as

soon as possible, especially in the presence of fever.

Once fever has persisted for longer than 24 hours,

antibiotics are required. In one woman in this study,

however, breast abscess was evident within the first

few hours of fever and in another woman without

fever, thus fever should be considered a non-specific

sign. Clinical assessment was the most important. The

ratio of breast abscess to mastitis was higher in

this series (46.2%) compared with that reported

in the literature (11.1%).3 This may have been due

to a difference in sampling methods or different

diagnostic criteria for mastitis. The difference

between a blocked duct and mastitis can be very

subtle. Presence of redness and tenderness in the

breast with little effort to clear the blockage may be

classified as mastitis. What is of more concern is the

possible delay in management that allows untreated

mastitis to progress to breast abscess. An abscess can

be drained through the duct manually, but needle

aspiration under ultrasound guidance or incision

may be required in some cases. If there is an incision,

the wound must be left open for continuous drainage

and the mother may be forced to stop breastfeeding.

Since most of these infections are due to

Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus, or Escherichia

coli, antibiotics chosen should be amoxicillin with

clavulanate, cloxacillin, or cefuroxime; all of which

are compatible with continuation of breastfeeding.3

Nipple pain

Nipple pain may indicate a blocked duct because the

duct beneath the areola is swollen. There should be

some tenderness although not as much as that of the

affected breast lobule. After relief of the blockage,

nipple pain will resolve.

A white spot at the nipple may also indicate a

blocked duct. Blockage of a lobule and then stasis of

milk at the opening of the duct can lead to further

blockage by milk that has a high fat or high calcium

content. This spot will be white in colour, sometimes

referred to as a bleb. It can be removed by milk

expression, needle or local application of vegetable

oil. This should not be confused with thrush.

Concern has already been raised about the

general overdiagnosis of fungal infection as a cause

of breast pain, nipple pain, or white spot.4 Patients

treated for a presumed ‘yeast infection’ might have

shown improvement in symptoms as a result of the

anti-inflammatory effect of the antifungal drugs

or because the blocked duct resolved on its own.

Fungal infection of the breast and nipple may be

considered if a blocked duct has been excluded and

is often associated with other risk factors. Examples

are consuming a diet with high sugar content that

promotes growth of fungus, mother having received

antibiotics, a maternal history of vaginal candidiasis,

or baby’s oral mucosa with thrush.4 All these risk

factors were not found in any of the mothers in this

study. Excruciating pain after a feed is a non-specific

sign. It is more likely to be due to a blocked duct

or inadequate emptying of the breast, as shown in

this study. These patients had failed to improve after

being given local or systemic antifungal treatment in

their previous consultations prior to presentation to

this clinic. Pain was relieved only after the blocked

duct was cleared.

Diet of lactating mothers

There was a general misunderstanding among the

lactating mothers that eating more animal foods

could improve milk supply. Previous studies have

shown that the protein intake of local lactating

mothers is much higher than that of those in other

countries. At 3 months postpartum, Hong Kong

mothers had a protein intake of 98 g/day5 compared

to 81 g/day in the UK6 and 80 g/day in Japan.7 In

the first month after delivery (known locally as the

confinement period), the protein intake was even

higher (133 g/day)5 than at 3 months. During this

month, local mothers usually consume a special diet

consisting of much more pork, fish, chicken, egg,

and milk.

The practice of eating a special diet with

additional animal foods during confinement may

be unique to Hong Kong Chinese population and is

likely a long Chinese tradition. The original rationale

was to replenish the blood loss of childbirth and

may have been necessary at a time when the general

population had barely enough food. Prior to the

1960s, our ancestors usually ate a plant-based diet,

with pork available only in the Chinese New Year

or during some festivals. There was very little over-nutrition.

Time has changed. The diet of adults

today is generally high in animal protein8 and fat.

Further increase will lead to new clinical problems,

not just weight gain in mothers but also increased

risk of blockage and inflammation in breastfeeding

mothers. A diet that contains much more meat

has been shown to be associated with higher

inflammatory index scores9 and one of these is C-reactive

protein.10

The quantity and quality of fat in breast milk

can be affected by the fat in the maternal diet.

Lactating mothers in Chongqing (a major city in

Southwest China) consumed a diet wherein fat

came from lard. Total fat in the breast milk was

higher in Chongqing: 38 g/L compared with 32 g/L in

Hong Kong.11 Chongqing mothers did not appear to

have problems of blocked ducts or mastitis. Thus, a

high-fat diet per se may not cause mastitis, it is the

quality of fat that matters. Mothers who consume

a diet high in saturated fat may be more prone to

duct blockage.3 Mothers with a recurrent blocked

duct were often advised to change their diet to one

with more polyunsaturated fat or use a supplement,

lecithin.3 A dietary source of lecithin is mainly soy

or eggs. It would appear to be a good practice for

lactating mothers in Chongqing to eat lots of eggs.

However, in view of the possibility of egg allergy,

Hong Kong mothers may be better advised to eat

more soy products. Mothers in this study group

appeared to eat very few soy products.

High milk production together with

inadequate emptying definitely poses a problem.

Many Hong Kong mothers took both Chinese

remedies (herbs, fish soups) and drank western teas

(eg fenugreek) to increase milk production. Nearly

all breastfeeding mothers had a breast pump. Some

mothers pumped milk more often to produce an

excess for later use. Indeed quite a number of the

studied mothers had plenty of stored milk in their

refrigerator. Working mothers may have stopped

pumping during weekends. Such irregular breast

emptying may cause the problem of milk stasis. The

presence of fatigue, stress, and an imbalanced diet

can encourage inflammation that can easily progress

to mastitis. Recurrence of blocked duct/mastitis may

occur if the mother’s diet and practice of feeding or

pumping are not corrected.

A diet rich in white sugar or corn syrup,

pastries, and cakes can enhance the growth of fungus

but was generally not observed in our subjects.

This may explain why fungal infection was rare. A

natural well-balanced diet with whole grains, plenty

of vegetables and fruits, and no excessive animal

products should be recommended. Refined sugary

foods, foods with chemicals, colouring agents, and

preservatives should be avoided.

Medical services

A substantial number of nurses had passed the

examination that qualified them as an International

Lactation Consultant. They worked mainly in

the maternity wards of hospitals and MCHCs in

Hong Kong. They were very successful in initiating

breastfeeding. Some hospitals ran a breastfeeding

clinic to support mothers after discharge from the

maternity ward but they were not available round the

clock. Most mothers with breastfeeding problems

attended a MCHC to seek for help. Other mothers

chose to see their family doctors. In general, doctors

had little training in dealing with problems related

to breastfeeding. In 2011, the Department of Health

produced a self-learning kit on breastfeeding for any

doctor who was interested, but it is difficult for the

public to identify such doctors.

Breast pain can sometimes be unbearable.

Some patients described it as worse than labour pain.

It is unknown from this study how many mothers

had stopped breastfeeding because of the pain or

how many ended up in hospital with a high fever and

abscess that required surgery. Many patients in this

study stated that after earlier treatment failed, they

had no idea where else to seek further help. Others

hesitated to seek medical help because they were

afraid they would be told to stop breastfeeding. The

mothers in this study were perhaps exceptional. They

had tried very hard to find a solution for their pain

even though it might have taken a number of days.

These mothers deserve a better medical service. The

Secretary for Food and Health has stated that the

government is very supportive of breastfeeding and

is ready to collaborate with health care professional

bodies or non-governmental organisations in

training personnel and promoting breastfeeding.12

Setting up breastfeeding clinics is the correct

approach. These clinics can be run by MCHCs or a

Baby-Friendly Hospital and should be full time and

open to all. Doctors and lactation consultants can

accumulate clinical experience faster and can then

act as professional trainers. There is also a need for

more local research on the diet and health of lactating

mothers, especially those in confinement, so that

appropriate education can be delivered to doctors,

lactation consultants, midwives, peer counsellors,

confinement nannies, and the public.

This study was limited by its retrospective

nature. There was a lack of standard protocols for

data recording and retrieval. Not all women were

followed up to determine if they had completely

recovered since it is difficult to do so in a private

clinic. What is certain is that those with engorgement

and a blocked duct felt immediate relief the moment

they left the clinic. It is also quite possible that many

cases of breast pain were treated by other doctors

and lactation consultants. The data of this study may

thus not be representative of Hong Kong in general.

Conclusion

Blocked duct was the most common cause of breast

pain in lactating mothers. Without prompt relief

it may progress to mastitis/breast abscess or the

mother may choose to stop breastfeeding. It may

be a suitable time for Hong Kong to set up one or

more public full-time breastfeeding clinics in order

to provide a better service for lactating mothers and

to facilitate professional training and research.

Declaration

The author has disclosed no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Baber FM. The current situation in Hong Kong. Hong

Kong Pract 1981;5:132-7.

2. Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative Hong Kong Association. Available from: http://www.babyfriendly.org.hk/en/breastfeeding-in-hk/breastfeeding-trend/. Accessed Feb 2016.

3. Lawrence RA, Lawrence RM. Breast feeding: a guide for

the medical profession. 5th ed. St Louis: Mosby; 1999:

273-83.

4. Wilson-Clay B, Hoover K. The breastfeeding atlas. 5th ed.

US: LactNews Press; 2013: 57-8.

5. Chan SM, Nelson EA, Leung SS, Cheng JC. Bone mineral

density and calcium metabolism of Hong Kong Chinese

postpartum women—a 1-y longitudinal study. Eur J Clin

Nutr 2005;59:868-76. Crossref

6. Black AE, Wiles SJ, Paul AA. The nutrient intakes of

pregnant and lactating mothers of good socio-economic

status in Cambridge, UK: some implications for

recommended daily allowances of minor nutrients. Br J

Nutr 1986;56:59-72. Crossref

7. Takimoto H, Yoshiike N, Katagiri A, Ishida H, Abe S.

Nutritional status of pregnant and lactating women in

Japan: a comparison with non-pregnant/non-lactating

controls in the National Nutrition Survey. J Obstet

Gynaecol Res 2003;29:96-103. Crossref

8. Leung SS, Woo J, Ho S, Lam TH, Janus ED. Hong Kong

dietary survey. Aust J Nutr Diet 1988;55(Suppl):S11-4.

9. Morimoto Y, Beckford F, Cooney RV, Franke AA,

Maskarinec G. Adherence to cancer prevention

recommendations and antioxidant and inflammatory

status in premenopausal women. Br J Nutr 2015;114:134-43. Crossref

10. Turner-McGrievy GM, Wirth MD, Shivappa N, et al.

Randomization to plant-based dietary approaches leads to

larger short-term improvements in Dietary Inflammatory

Index scores and macronutrient intake compared with diets

that contain meat. Nutr Res 2015;35:97-106. Crossref

11. Chen ZY, Kwan KY, Tong KK, Ratnayake WM, Li HQ,

Leung SS. Breast milk fatty acid composition: a comparative

study between Hong Kong and Chongqing Chinese. Lipids

1997;32:1061-7. Crossref

12. Hong Kong Paediatric Society, Hong Kong Paediatric

Foundation. Summit on Breastfeeding and Early Childhood

Nutrition in the First 1000 Days 2015; Abstract: 18.