Hong Kong Med J 2016 Aug;22(4):306–13 | Epub 3 Jun 2016

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj154737

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Validity and reliability of the Chinese version of the Insulin Treatment Appraisal Scale among primary care patients in Hong Kong

KP Lee, FRACGP, MSc Mental Health (CUHK)

Department of Family Medicine and Public Health Unit, Kowloon West Cluster, Hospital Authority, 118 Shatin Pass Road, Hong Kong

This paper was presented at the Hospital Authority Convention, 18-19 May

2015, Hong Kong.

Corresponding author: Dr KP Lee (ineric_2000@yahoo.com.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: Patients with diabetes mellitus

often delay insulin initiation and titration due to

psychological factors. This phenomenon is known

as ‘psychological insulin resistance’. Tools that

identify psychological insulin resistance are valuable

for detecting its causes and can lead to appropriate

counselling. The Insulin Treatment Appraisal Scale

was initially developed for western populations

and has been translated and validated to measure

psychological insulin resistance in Taiwan (Chinese

version of the Insulin Treatment Appraisal Scale, C-ITAS).

The current study examined the prevalence

of psychological insulin resistance and the validity of

the C-ITAS in a local population.

Methods: This cross-sectional study involved 360

patients with diabetes mellitus from a government-funded

general out-patient clinic who completed the

C-ITAS questionnaire. The total C-ITAS score was

compared for patients with psychological insulin

resistance and those without, and the internal

consistency and test-retest reliability of the C-ITAS

were calculated. An exploratory factor analysis was

used to identify factors within the C-ITAS.

Results: The prevalence of psychological insulin

resistance was 44.9%. The internal consistency of

the scale was high (Cronbach’s alpha=0.78). The

test-retest reliability was positive with all C-ITAS

questions (0.294-0.725). The mean C-ITAS

score was significantly higher among patients with

psychological insulin resistance than those without

(42.42 vs 35.78; P<0.001). The exploratory factor

analysis, however, failed to identify the two clear

factors identified in the original validation study.

Conclusions: The C-ITAS appears to be a

feasible and potentially useful tool for identifying

psychological insulin resistance, but additional

validation or translation is required before it can be widely used clinically.

New knowledge added by this study

- The Chinese version of the Insulin Treatment Appraisal Scale (C-ITAS) is a potentially useful and reliable tool to understand patients’ underlying reasons for psychological insulin resistance (PIR).

- Further validation of C-ITAS is needed.

- Understanding patients’ PIR can lead to appropriate and patient-centred counselling.

- Validation of C-ITAS can facilitate a comparison of local PIR studies with those in other countries.

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) is a prevalent and

increasingly common disease worldwide.1 It is

estimated to affect 10% of the Hong Kong (HK)

population (approximately 700 000 people).2

Achieving satisfactory DM control during the

early disease course can reduce DM-induced

microvascular and macrovascular complications (ie

the ‘legacy effect’).3 4 These benefits were maintained

in patients in a tight DM-control group even though

their glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) level

became similar to those in the control group after

the end of the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes

Study.4 It was proposed that a ‘reverse legacy effect’

also persists: “intensive glycaemic intervention

started late in the natural course of diabetes seems

disappointingly ineffective in limiting cardiovascular

events”.5 6 Very tight control may even result in mortality.7 8 Therefore, achieving tight HbA1c control early via lifestyle changes and the use of

medications including insulin is important.

Because of the progressive nature of DM, most

patients eventually require insulin.9 Despite robust

evidence of the benefits of early strict HbA1c control,

patients often delay insulin initiation and titration.

In a UK study, 50% of patients with DM delayed

insulin initiation despite suboptimal control for 5

years, regardless of the presence of complications.10

Their reluctance to initiate insulin use10 11 12 and its

subsequent titration13 is known as ‘psychological

insulin resistance’ (PIR). The prevalence of PIR has

been estimated to be higher in Singapore (70.6%)11

than in western countries (approximately 20%-40%).12 A HK survey of 97 participants found a similarly high prevalence of PIR (72.1%).14 Previous

studies conducted in western countries have

identified several factors that can lead to PIR.11 12 13

These reasons might differ in Asian countries,

however.15 16 Recently, a local primary care research group developed a scale, Chinese Attitudes to

Starting Insulin questionnaire, to identify barriers

to insulin initiation in insulin-naïve patients with

DM.16 These investigators found that Asian patients

might be more affected by the availability of social

support and that cultural differences might also

play a role. For example, Chinese patients are more

likely to combine western medical treatments with

traditional Chinese medicine17 and might believe

that hypoglycaemic agents cause renal toxicity.18

Doctors, particularly primary care physicians,

can be insensitive to patients’ psychological needs;

physicians often fail to recognise psychological

needs19 and might incorrectly identify the

reasons for a patient’s PIR.20 21 Identifying one’s

psychological needs might be hindered in HK due

to short consultation times (lasting an average of

5-7 minutes per consultation). A limited number of

longer sessions may be offered to DM patients with

difficult glycaemic control, but the time limit would

be 10 to 14 minutes. Therefore, a quick tool to help

identify PIR and its underlying causes might help

general practice physicians optimise care for their

patients with DM.12 The Insulin Treatment Appraisal

Scale (ITAS) was developed for this purpose.22 The

Chinese version of the ITAS (C-ITAS) was validated

in Taiwan,23 and has been used in Taiwan15 to investigate the underlying causes of PIR. Validating

C-ITAS scores might enable direct comparisons of data between local and international studies. The

C-ITAS might also be used to help local primary

care clinicians identify PIR and offer appropriate

counselling. The ITAS is sensitive to changes in PIR

throughout the course of DM.24

This study is the first to be conducted in HK to

examine the prevalence of PIR and the validity and

reliability of the C-ITAS in our local population.

Methods

This research has been approved by the Research

Ethics Committee at Kowloon West Cluster, Hospital

Authority.

Participants

Participants were recruited from a government-funded

primary care general out-patient clinic in HK

from July to September 2013. Written consent was

obtained when the participants were approached

by the research assistant. The investigator’s contact

information was given to each participant if they

had concerns after the administration of the

questionnaire. Patients who fulfilled the following

criteria were recruited: (1) diagnosed with type 2 DM

as defined by the World Health Organization25 for

≥6 months; (2) aged 30 years or above; (3) of Chinese

ethnicity; (4) able to communicate effectively in

Cantonese or Mandarin; and (5) had the mental

capacity to provide informed written consent. The

exclusion criteria were severe sensory deficits,

severe mental illness (eg dementia, psychosis, or

mental retardation), or any other health condition

that compromised the ability to comprehend and

complete the questionnaire. The required sample size

was calculated from the estimated prevalence rate of

PIR in the primary care setting. To achieve a 95%

confidence interval with a margin of error of 5% and

an estimated 70% prevalence of PIR among patients

with DM in public primary care,11 14 the required sample size was estimated to be 312 patients. To

compensate for the predicted 20% refusal rate, at

least 390 patients were recruited.

A list of DM patients who would attend the

clinic the next day was obtained daily. From that list,

40 patients were randomly selected by computer (25

in the morning and 15 in the afternoon). A reminder

was set in the clinical computer system such that

clinic staff were alerted once the patient attended

his or her appointment. The procedure was repeated

until the number of patients recruited exceeded 390,

which was checked at clinic closing time.

Patients were encouraged to complete the

questionnaire unaided because the C-ITAS is self-administered.

Because the majority of patients who

attend public primary care clinics are of lower socio-economic

status and education level, those who had

difficulty completing the questionnaire were assisted

by research assistants who were trained by the

principal investigator.

Each patient was asked whether he or she

was willing to have insulin started or titrated upon

his or her case doctor’s suggestion. The response

options included “strongly unwilling”, “unwilling”,

“might consider it”, “willing”, and “very willing”.

Demographic data were collected, and clinical data

(eg the presence of DM complications, insulin use,

and control of DM and lipid levels) were retrieved

from a computer database.

Insulin Treatment Appraisal Scale

The ITAS is a 20-item instrument that contains 16

negative and four positive statements that appraise

insulin treatment. Each statement is ranked using

a 5-point Likert-type scale from 1 to 5. Positive

scores are reversed to allow for summation. The

total possible score ranges from 0 to 80. A higher

score signifies a more negative appraisal of insulin.

The ITAS was developed for clinical use to measure

PIR.22 No cut-off score is used to diagnose PIR. Of

those who completed the clinical interview, 26 were

selected for phone interview 2 to 4 weeks later to

examine test-retest reliability. Because of the lack

of a written language difference between Taiwan

and HK, the validated C-ITAS was used with the

permission of the Taiwan research group.

Statistical analyses

The C-ITAS was examined for its internal reliability

using Cronbach’s alpha, the test-retest reliability

was assessed using Pearson’s correlation of test

scores and retest scores, and construct validity

was assessed using an exploratory factor analysis

(EFA) [using Oblimin rotation as this was used in

the original development study of ITAS22]. Patients

who answered “strongly unwilling” or “unwilling”

to the question “Would you agree to start or titrate

insulin treatment if advised by your case doctor?”

were classified as having PIR. Descriptive statistics

were used to describe the prevalence of PIR. Each

C-ITAS item was dichotomised as “unwilling”

(scores of 1 and 2) or “neutral/willing” (scores of

3 to 5); this dichotomy was created to assess the

difference between patients with and without PIR.

The responses of the patients with or without PIR

were compared using a Chi squared test.

Results

Participants

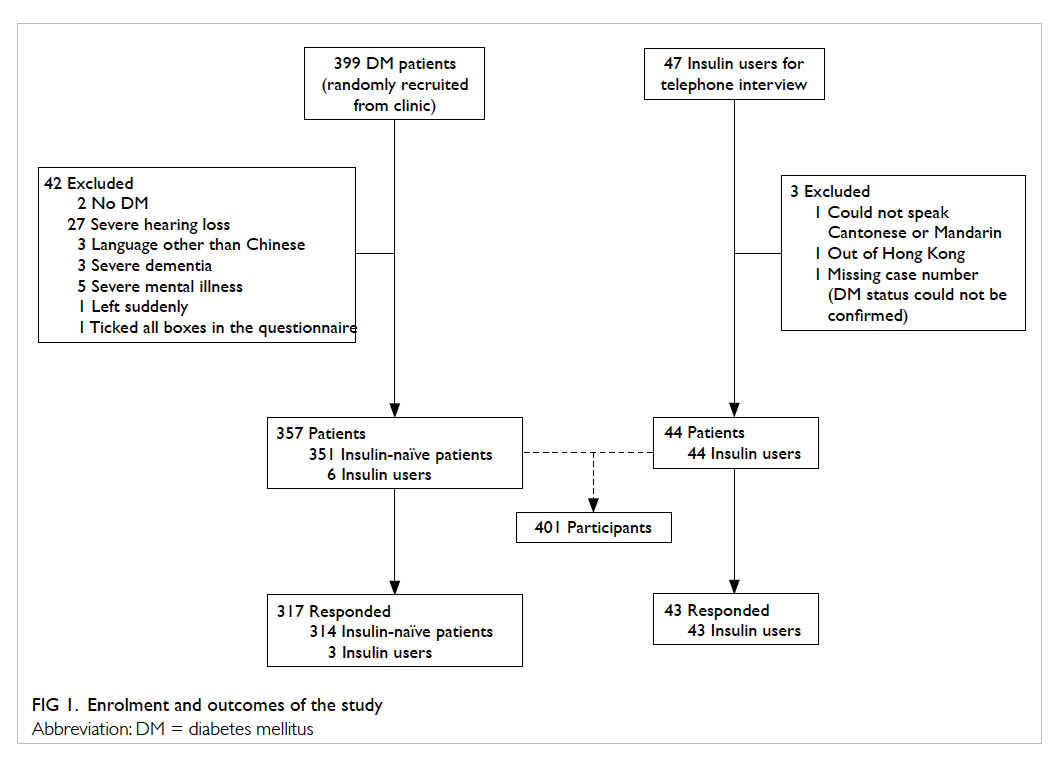

A total of 399 patients with DM were randomly

selected from the clinical database and approached

by the research team (Fig 1). Of them, 42 patients

were excluded due to the following circumstances: two

patients were incorrectly diagnosed with DM; 27 had

severely impaired hearing not compensated for with

the use of hearing aids; three spoke languages other than

Cantonese or Mandarin; eight had severe psychiatric

illness such as dementia, psychosis, or mental

retardation; one left at the beginning of the interview

when called into a consultation room; and one was

excluded for checking all boxes of the questionnaire.

In addition to the insulin-naïve patients with

DM who were recruited as outlined above, all of

the current insulin users who were not interviewed

during the above period (47 patients) were invited to

participate in this study and were interviewed over

the phone; of whom three

were excluded for the following reasons: one could

not speak Cantonese or Mandarin, one was out of HK

during the interview period, and one questionnaire was

invalid due to a missing subject case number.

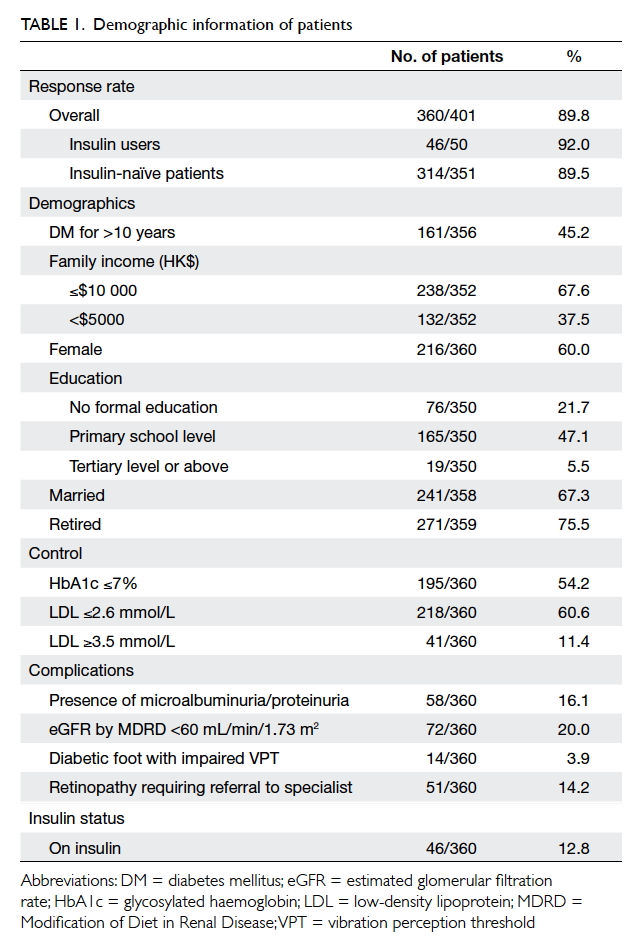

The overall response rate was 89.8% (n=360):

89.5% (n=314) for the insulin-naïve patients

and 92.0% (n=46) for the insulin users. Other

demographic data are shown in Table 1.

A total of 12.8% (n=46/360) of participants

were insulin users. Patients with HbA1c ≥7% (≥53

mmol/mol; 21.6%) were more likely to be on insulin

than those with HbA1c <7% (<53 mmol/mol; 2.9%;

P<0.001). The HbA1c level was not significantly

associated with the presence of DM complications in

the current study. Of all participants, 96.3% received

DM complication screening within 2 years, which

was a nurse-led clinical service to screen for DM

complications and provide counselling.

Non-respondents were significantly older

(mean age=72.32 vs 67.17 years, t test: P<0.001),

less likely to agree to titrate insulin (for current

insulin users), and less educated (91.7% educated

up to primary level vs 68.9%; Chi squared test;

P=0.004). The differences with regard to the other

demographics, including DM complication rate,

insulin use status, marriage, work, family income,

and gender were not significant.

The prevalence of PIR was 44.9% (141/314; 95%

confidence interval [CI], 39.4% to 50.4%) in insulin-naïve

patients; in contrast, the PIR rate was 6.8%

(3/44; 95% CI, -0.64% to 14.24%) in current insulin

users.

The questionnaire

The internal consistency of the C-ITAS questionnaire

was high, with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.78. The original

ITAS was designed to have 16 negative and four

positive statements. Cronbach’s alpha was calculated

separately for the negative and positive statements,

yielding values of 0.812 and 0.738, respectively.

Within the negative statement scale, removing two

negatively stated questions individually, including

Q1, “Insulin signifies failure with pre-insulin

therapy”, and Q18, “Taking insulin causes family/friends to be more concerned” improved the overall Cronbach’s alpha to 0.819 and 0.825, respectively.

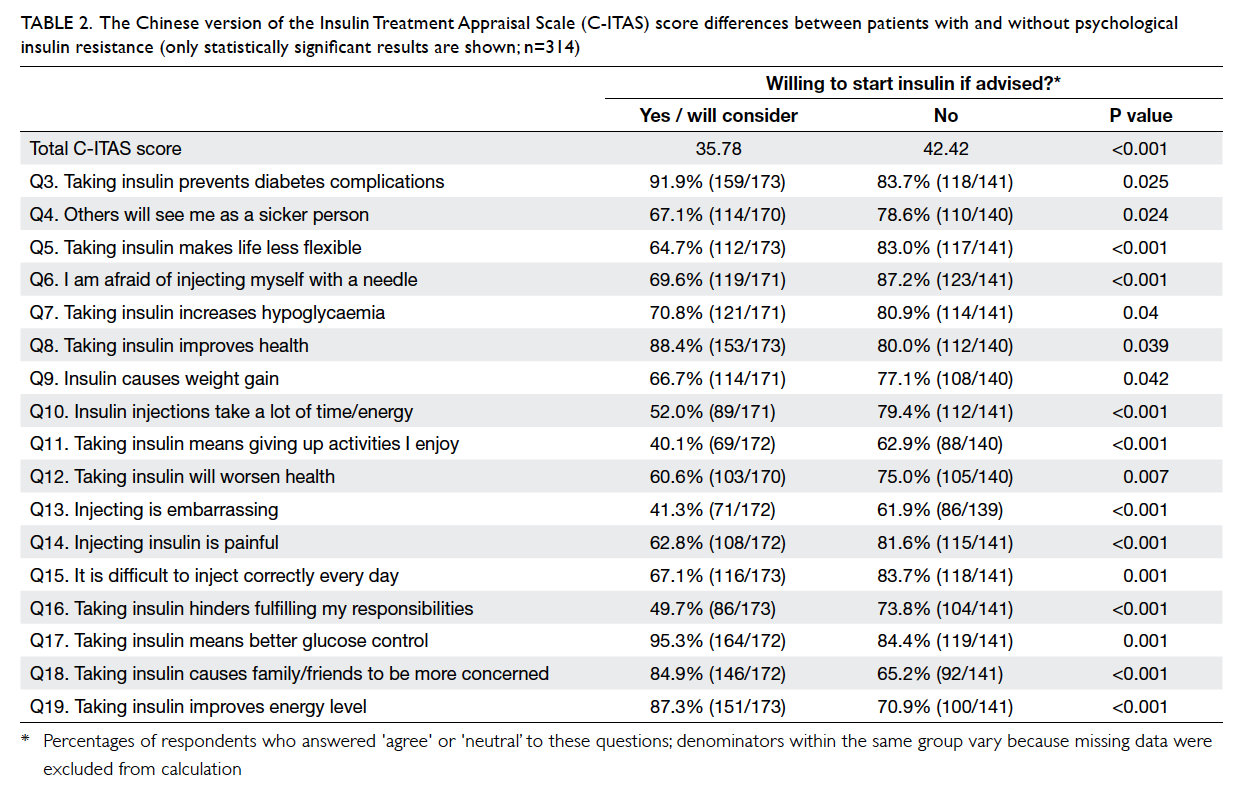

Of the 20 individual questions within the

C-ITAS, answers to 17 questions were significantly

different in the expected direction between patients

with PIR and those without. Importantly, Q18,

“Taking insulin causes family/friends to be

more concerned” was originally designed to detect

a negative view towards insulin use; however, more

insulin-accepting patients agreed with the statement

(Table 2).

Table 2. The Chinese version of the Insulin Treatment Appraisal Scale (C-ITAS) score differences between patients with and without psychological insulin resistance (only statistically significant results are shown; n=314)

The total C-ITAS scores, as described above,

were higher among participants who refused insulin

initiation (42.42 vs 35.78; t test, P<0.001). The test-retest

reliability for each question ranged from 0.294

to 0.725, and 13 questions were significant (P<0.05).

The test-retest reliability of the overall scores as

defined above was 0.571 (P=0.002).

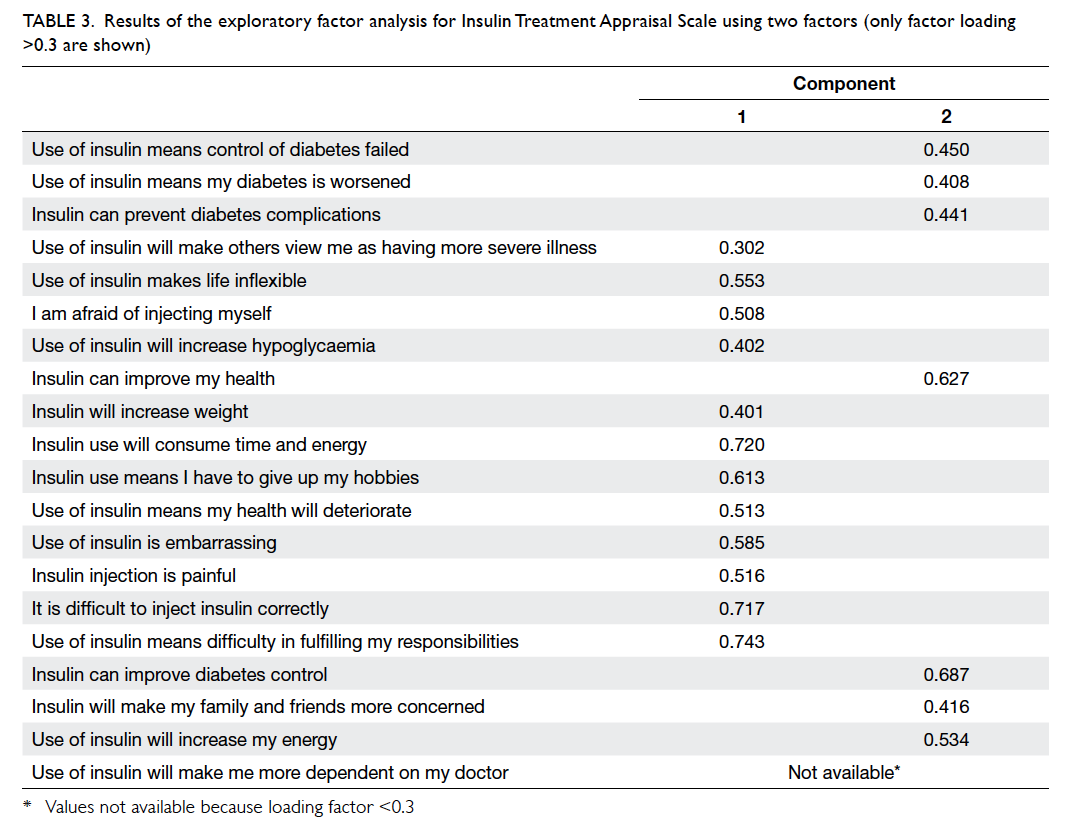

The EFA identified five factors with an eigenvalue of >1. Nonetheless, the scree plot correctly identified two factors within the questionnaire.

When two factors were extracted using an Oblimin

rotation, a few negative statements including Q18

were significantly associated with the other positive

statements (Table 3). The three-, four-, and five-factor solutions were calculated as suggested by the eigenvalue, which did not provide better representation of

the latent structure of ITAS.

Table 3. Results of the exploratory factor analysis for Insulin Treatment Appraisal Scale using two factors (only factor loading >0.3 are shown)

In the EFA, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure

of sampling adequacy was 0.834 and Bartlett’s test

of sphericity was significant (P<0.001), and signified

adequate sample size for the test.

Discussion

Because the participants were old and not well

educated, difficulties in answering the C-ITAS were

expected. This assumption was further supported by

the fact that the non-respondents were less educated

and were older than the respondents. Nevertheless

a high proportion of participants (89.8%) were able

to complete the entire questionnaire. Additional

research might be necessary to assess the response

rate if the questionnaire is self-administered because

the staffing at our public out-patient clinics was

limited. The use of ITAS might be limited if it cannot

be self-administered because it was developed as a

self-administered tool.

Prevalence of psychological insulin resistance

It is surprising that the prevalence of PIR was not

as high as reported by previous studies.11 14 More than 50% of patients were willing to consider or accept

insulin if suggested by their primary doctor. This

finding might be because of differences in the patient

cohorts or the improvements made to the PIR over

the years due to patient education. Only 53 patients

with DM out of the thousands of patients followed

up in our clinic were started on insulin. Alternative

reasons might explain the low rates of insulin use (eg

physician beliefs and competencies regarding the

use of insulin), and might merit additional research.

Validity and reliability of the questionnaire

The C-ITAS was reliable because it yielded high

Cronbach’s alpha scores (0.738-0.812) and correctly

provided a higher score for patients who resisted

insulin use. It identified many different attitudes

towards insulin use; in the current study, answers to

17 out of 20 of the C-ITAS items significantly differed

between patients who resisted insulin and those who

did not, whereas a previous study showed that only

four questions were able to make this distinction.12

This may be because individual patients had multiple

concerns and many different attitudes towards

insulin use.

Although the test-retest reliability value of

all ITAS items was positive, the values were low,

ranging from 0.294 to 0.725 for individual C-ITAS

questions. In the present study, the C-ITAS was

completed either via a personal interview with a

research assistant or by self-administration. Retests

were administered via telephone interviews by either

the research assistant or the principal investigator.

Therefore, the low test-retest reliability scores might

be because of the different means of administration

or due to the different interviewers. Conversely,

this difference might reflect the actual low test-retest

reliability of the current C-ITAS that requires

additional validation.

Question 18, “Taking insulin causes family/friends to be more concerned”,

merits additional discussion. Originally designed

as a negative statement, it is expected that patient

resistance to insulin would positively predict the

score. The reverse was true, however, in the current

study (Table 2). When the statement was reviewed

by six family physicians and one psychiatrist, the

word “concerned” (關心) was translated into a word

in Chinese that can also mean “caring” (使用胰島素使家人和朋友對我更關心). It is likely that patients

understood the question as, “Taking insulin causes

my family and friends to be more caring toward me”.

Because Q18 was meant to be a negative statement,

it is more appropriate to translate its meaning to

“worry”. This supposition is supported by both the

Cronbach’s alpha analysis, in which exclusion of

Q18 improved the value of Cronbach’s alpha,

and the factor analysis, where Q18 was regarded as a

factor with the other positive statements. The factor

analysis did not show a two-factor structure within

the ITAS, as in the previous study.22 As the factor

analysis table notes (Table 3), when set as a two-factor

construct, no trend can be drawn for these

two groups. The factor analyses of the first study

on the development of the ITAS22 and the validation

study in Taiwan23 both showed a two-factor construct,

with the two factors being positive statements and

negative statements. This finding might reflect the

previously noted translation problem; alternatively,

our local community might have had a different

set of causes for PIR. This finding suggests that a

dialectic or cultural difference remains between HK

and Taiwan, despite a shared written language.26 27 Additional validation of the C-ITAS in our local

population is likely necessary.

Strengths and weaknesses

The strengths of our study include its large sample

size, the use of random sampling, and the high

response rate. The use of an internationally validated

questionnaire might aid comparison with results

from other countries. The C-ITAS, however, might

require additional validation as noted above.

The statement proposing the use of insulin to

patients was hypothetical. For example, estimated

PIR rates might be lower when patients perceive

their disease as having deteriorated so that additional

intervention is necessary.

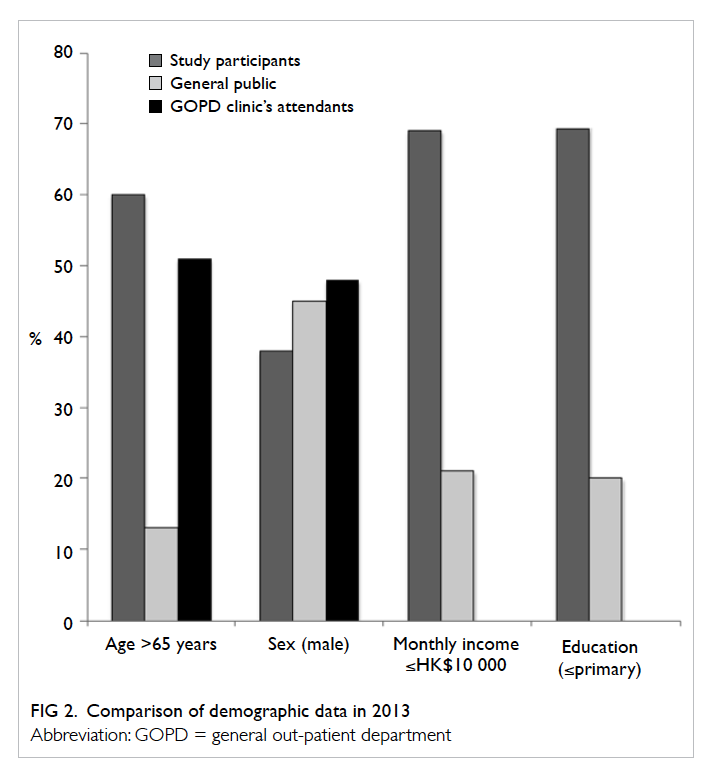

This study was conducted in a major

government-funded clinic in Hong Kong, and the

demographics of the participants were more similar

to those of other government clinics than to the

general population (Fig 2). The extent to which the

results can be generalised to other countries and to

other social classes (eg wealthy patients attending

private primary clinics) is not known.

A majority of the patients in the current study

were insulin-naïve. Despite including all available

insulin users in the clinic, the number of insulin

users was small, and limits the potential applicability

of this study’s results to secondary or tertiary care

where many patients may be on insulin.

The study also did not distinguish between

questionnaires that were completed with the help of

research staff and those that were self-administered.

The influence of different administration methods

on the outcome has not been previously described.

For example, when participants did not understand

a statement, the trained research assistant may

use her own words to elaborate and explain it to

the participant and thus may alter the statement’s

original sentence structure or intended meaning.

Another weakness was that data on

macrovascular complications were not collected.

Microvascular complications were well documented

during the DM complication screening and were

easily traceable. The tracing of macrovascular

complications, however, was difficult because

diagnostic coding needed to be entered or the

complication needed to be mentioned in the latest

case record by the respective doctors, and missed

coding for macrovascular complications was not

uncommon.

Conclusions

The prevalence of PIR was 44.9% in our population,

which is less than that previously estimated. Tools such as

the C-ITAS can improve physician’s understanding

of patient views on insulin and might help physicians

to appropriately counsel their patients. The C-ITAS

may provide clues to patients’ knowledge about

insulin use, eg the risk of hypoglycaemia or the

side-effects of obesity. Despite good psychometric

properties such as high internal consistency,

there is a translation issue in at least one of the 20

statements. Health care professionals who wish to

use the C-ITAS clinically should be aware of the

instrument’s limitations.

Acknowledgements

The author expresses gratitude to Prof Sandra

Chan for her teaching and guidance regarding this

research; to Prof Samuel Wong for his kind and

timely advice; and to Drs YK Yiu and SN Fu and the

Department of Family Medicine, Kowloon West

Cluster, HK for their research support. The author

would like to thank Ms Man-ping Chang and her

team for the development of the C-ITAS and for

allowing the use of the C-ITAS in the current study.

Declaration

The author has disclosed no conflicts of interest.

References

1. International Diabetes Federation. IDF diabetes atlas

update 2012. Available from: http://www.idf.org/sites/default/files/EN_6E_Atlas_Full_0.pdf. Accessed 1 Apr

2013.

2. Hong Kong Department of Health. Hong Kong reference

framework for diabetes care for adults in primary care

settings. Available from: http://www.pco.gov.hk/english/resource/professionals_diabetes_pdf.html. Accessed 1

Apr 2013.

3. Genuth S, Eastman R, Kahn R, et al. Implications of the

United Kingdom prospective diabetes study. Diabetes Care

2003;26 Suppl 1:S28-32. Crossref

4. Davis TM, Colagiuri S, United Kingdom Prospective

Diabetes Study. The continuing legacy of the United

Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study. Med J Aust

2004;180:104-5.

5. ADVANCE Collaborative Group, Patel A, MacMahon

S, et al. Intensive blood glucose control and vascular

outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med

2008;358:2560-72. Crossref

6. Riddle MC, Yuen KC. Reevaluating goals of insulin therapy:

perspectives from large clinical trials. Endocrinol Metab

Clin North Am 2012;41:41-56. Crossref

7. Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes Study

Group, Gerstein HC, Miller ME, et al. Effects of intensive

glucose lowering in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med

2008;358:2545-59. Crossref

8. ACCORD Study Group, Gerstein HC, Miller ME, et

al. Long-term effects of intensive glucose lowering on

cardiovascular outcomes. N Engl J Med 2011;364:818-28. Crossref

9. Turner RC, Cull CA, Frighi V, Holman RR. Glycemic control

with diet, sulfonylurea, metformin, or insulin in patients

with type 2 diabetes mellitus: progressive requirement for

multiple therapies (UKPDS 49). UK Prospective Diabetes

Study (UKPDS) Group. JAMA 1999;281:2005-12. Crossref

10. Rubino A, McQuay LJ, Gough SC, Kvasz M, Tennis P.

Delayed initiation of subcutaneous insulin therapy after

failure of oral glucose-lowering agents in patients with

type 2 diabetes: a population-based analysis in the UK.

Diabet Med 2007;24:1412-8. Crossref

11. Wong S, Lee J, Ko Y, Chong MF, Lam CK, Tang WE.

Perceptions of insulin therapy amongst Asian patients with

diabetes in Singapore. Diabet Med 2011;28:206-11. Crossref

12. Woudenberg YJ, Lucas C, Latour C, Scholte op Reimer WJ.

Acceptance of insulin therapy: a long shot? Psychological

insulin resistance in primary care. Diabet Med 2012;29:796-802. Crossref

13. Jenkins N, Hallowell N, Farmer AJ, Holman RR, Lawton

J. Participants’ experiences of intensifying insulin therapy

during the Treating to Target in Type 2 diabetes (4-T) trial:

qualitative interview study. Diabet Med 2011;28:543-8. Crossref

14. Yiu MP, Cheung KL, Chan KW, et al. A questionnaire study

to analyze the reasons of insulin refusal of DM patients

on maximum dose of oral hypoglycemic agents (OHA)

among 3 GOPCs in Kowloon West Cluster. 2010. Available

from: http://www.ha.org.hk/haconvention/hac2010/proceedings/pdf/Poster/spp-p5-38.pdf. Accessed 1 Apr

2013.

15. Chen CC, Chang MP, Hsieh MH, Huang CY, Liao LN, Li

TC. Evaluation of perception of insulin therapy among

Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes

Metab 2011;37:389-94. Crossref

16. Fu SN, Chin WY, Wong CK, et al. Development and

validation of the Chinese Attitudes to Starting Insulin

questionnaire (Ch-ASIQ) for primary care patients with

type 2 diabetes. PLoS One 2013;8:e78933. Crossref

17. Ma GX. Between two worlds: the use of traditional

and western health services by Chinese immigrants. J

Community Health 1999;24:421-37. Crossref

18. Lai WA, Lew-Ting CY, Chie WC. How diabetic patients

think about and manage their illness in Taiwan. Diabet

Med 2005;22:286-92. Crossref

19. Martin A, Rief W, Klaiberg A, Braehler E. Validity of the

Brief Patient Health Questionnaire Mood Scale (PHQ-9) in

the general population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2006;28:71-7. Crossref

20. Peyrot M, Rubin RR, Khunti K. Addressing barriers to

initiation of insulin in patients with type 2 diabetes. Prim

Care Diabetes 2010;4 Suppl 1:S11-8. Crossref

21. Brod M, Kongsø JH, Lessard S, Christensen TL.

Psychological insulin resistance: patient beliefs and

implications for diabetes management. Qual Life Res

2009;18:23-32. Crossref

22. Snoek FJ, Skovlund SE, Pouwer F. Development and

validation of the insulin treatment appraisal scale (ITAS) in

patients with type 2 diabetes. Health Qual Life Outcomes

2007;5:69. Crossref

23. Chang MP, Huang CY, Li TC, Liao LN, Chen CC. Validation

of the Chinese version of the insulin treatment appraisal

scale. J Diabetes Investig 2010;1(Suppl 1):88.

24. Hermanns N, Mahr M, Kulzer B, Skovlund SE, Haak T.

Barriers towards insulin therapy in type 2 diabetic patients:

results of an observational longitudinal study. Health Qual

Life Outcomes 2010;8:113. Crossref

25. World Health Organization. About diabetes 2013. Available

from: http://www.who.int/diabetes/action_online/basics/en/index1.html. Accessed 1 Feb 2013.

26. Chow KM, Chan CW, Choi KC, et al. Psychometric

properties of the Chinese version of Sexual Function After

Gynecologic Illness Scale (SFAGIS). Support Care Cancer

2013;21:3079-84. Crossref

27. Tang DY, Liu AC, Leung MH, Siu BW. Antisocial

Personality Disorder Subscale (Chinese version) of the

Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV Axis II

disorders: validation study in Cantonese-speaking Hong

Kong Chinese. East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2013;23:37-44.