DOI: 10.12809/hkmj144419

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

A rare but serious complication of continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis: delayed perforation of the colon by the Tenckhoff catheter

PY Chu, FRCR; KL Siu, FRCR

Department of Diagnostic Radiology, Tuen Mun Hospital, Tuen Mun, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr PY Chu (idleadam@hotmail.com)

Case report

A 68-year-old male had end-stage renal failure

due to diabetes mellitus. He underwent Tenckhoff

catheter insertion in 2013 for continuous ambulatory

peritoneal dialysis (CAPD). The catheter was flushed

regularly once a week and was functional in the first

2 months following insertion.

The catheter became blocked 2 months

following insertion after an episode of CAPD

peritonitis. Peritoneal dialysate showed scanty

growth of Stenotrophomonas (Xanthomonas)

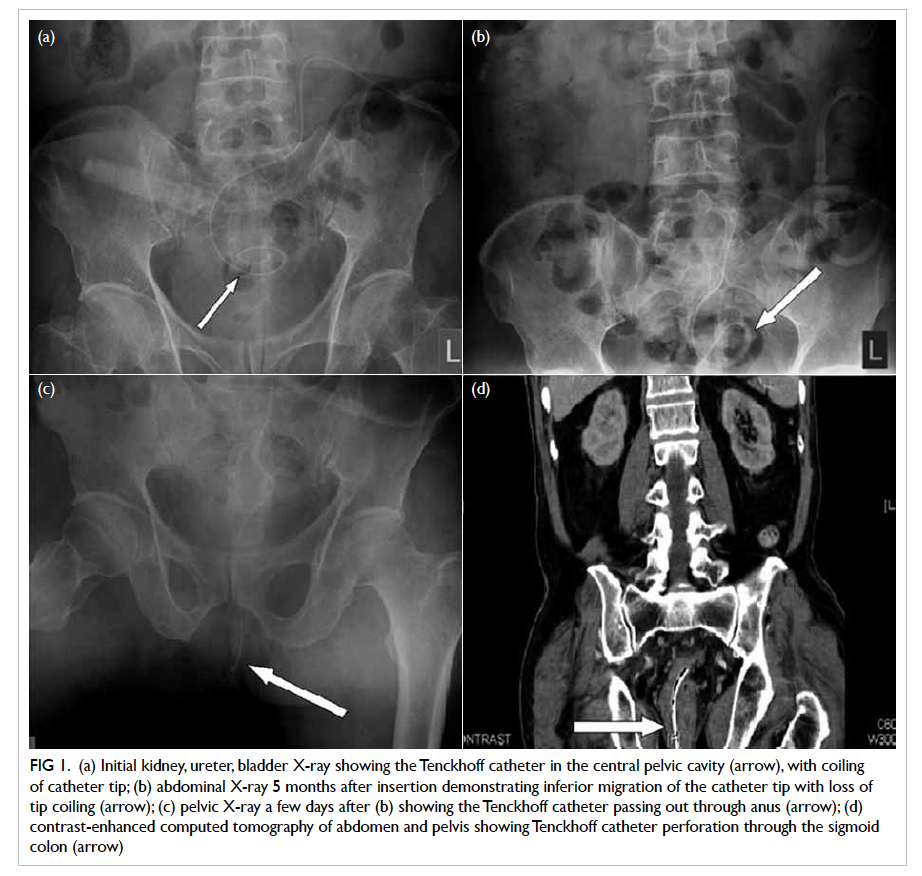

maltophilia. Kidney, ureter, and bladder X-ray (KUB)

was ordered to identify catheter tip position that

was subsequently revealed to be in the central part

of the pelvic cavity (Fig 1a). The cause of blockage was suspected to be omental wrap. Omentectomy

was planned and the Tenckhoff catheter was left

in situ; CAPD peritonitis was successfully treated

with antibiotics and the patient was discharged. The

peritoneal membrane was rested for 2 weeks and

the patient maintained on temporary twice-weekly

haemodialysis.

Figure 1. (a) Initial kidney, ureter, bladder X-ray showing the Tenckhoff catheter in the central pelvic cavity (arrow), with coiling of catheter tip; (b) abdominal X-ray 5 months after insertion demonstrating inferior migration of the catheter tip with loss of tip coiling (arrow); (c) pelvic X-ray a few days after (b) showing the Tenckhoff catheter passing out through anus (arrow); (d) contrast-enhanced computed tomography of abdomen and pelvis showing Tenckhoff catheter perforation through the sigmoid colon (arrow)

The patient was admitted to Tuen Mun Hospital

again in early 2014 because of fall. Computed

tomographic (CT) brain revealed a significant left

acute subdural haemorrhage. Urgent craniotomy

with clot evacuation was performed. At that time,

abdominal X-ray demonstrated inferior migration of

the catheter tip with loss of coiling of the distal tip

(Fig 1b). A few days later, the tip of Tenckhoff catheter was noticed in the anus of the patient. Follow-up KUB

confirmed the clinical finding (Fig 1c).

The patient had no symptoms or signs of

acute peritonitis. Contrast-enhanced CT abdomen

and pelvis confirmed perforation of the Tenckhoff

catheter through the sigmoid colon with the tip in

the anus (Fig 1d).

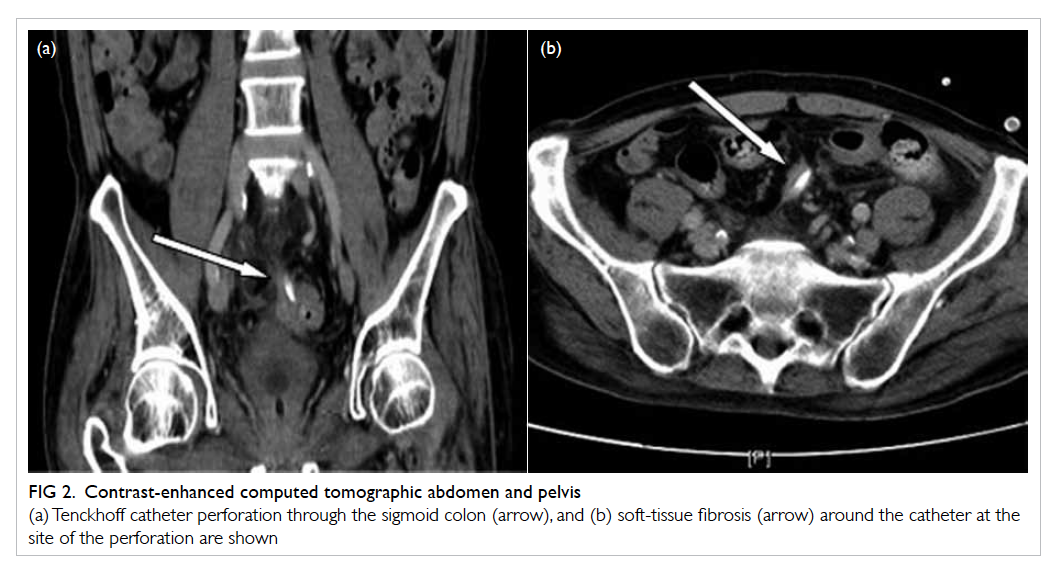

The contrast-enhanced CT demonstrated

Tenckhoff catheter perforation through the sigmoid

colon (Fig 2a) with soft-tissue fibrosis around the catheter at the site of the perforation (Fig 2b). There was no ascites or inflammatory fluid collection.

Contrast enema showed no evidence of contrast

extravasation.

Figure 2. Contrast-enhanced computed tomographic abdomen and pelvis

(a) Tenckhoff catheter perforation through the sigmoid colon (arrow), and (b) soft-tissue fibrosis (arrow) around the catheter at the site of the perforation are shown

The patient became chair-bound after the head

injury. It was decided not to remove or reposition

the Tenckhoff catheter or perform omentectomy.

The rectal side of the catheter was cut short.

Discussion

The pathogenesis of late perforation of the bowel has

been proposed to involve intimate contact between

the peritoneal catheter and the intestinal wall.

The continuous pressure causes local ischaemia,

eventually leading to erosion, laceration, and frank

perforation.1 Lack of fluid in the peritoneal space

after cessation of CAPD predisposes to pressure-induced

necrosis because of loss of the fluid

cushion.2 3 In our patient, perforation was unlikely

when the catheter was in daily use because it did not

come into continuous close contact with the bowel

for any long period of time.4

In most previous studies, delayed perforation

of the bowel was associated with acute peritonitis.1 3 5 6

Kagan and Bar-Khayim1 reviewed the publications

from 1980 to 1995 and identified 24 cases of bowel

perforation during the study period. All cases were

associated with acute peritonitis, with 29% mortality

and significant morbidity. The age of patients ranged

from 22 to 80 years, with no gender predominance.

The time to bowel perforation also ranged broadly

from 0.5 to 96 months after initiation of dialysis.

Sigmoid was the most common site of perforation,

accounting for 14 of the 24 cases. Asymptomatic

delayed perforation of the bowel by Tenckhoff

catheter was rarely reported.7 8

Our patient had acute peritonitis in late 2013.

The KUB showed normal position of Tenckhoff

catheter (Fig 1a) . Since the Tenckhoff catheter was not functioning, omental wrap was suspected.

Later X-rays revealed progressive inferior

migration of the catheter and loss of coiling of the

catheter tip, suggesting perforation of the bowel (Figs 1b and 1c). The CT abdomen and pelvis confirmed

perforation of the sigmoid by the Tenckhoff catheter

in addition to soft-tissue fibrosis around the catheter

tip (Figs 1d and 2).

In our case, in addition to the lack of peritoneal

dialysis fluid, there were probably peritoneal

adhesions arising from previous peritonitis that

resulted in decreased bowel mobility. This in turn

created a predisposition to impingement of bowel

loops by the Tenckhoff catheter that subsequently

led to pressure erosion and perforation.

The patient had no clinical or radiological

evidence of peritonitis, possibly due to plugging of

the bowel perforation site by the catheter and later

sealed off by inflammatory adhesion and fibrosis.

Thus, there was no leakage of faecal material from

the sigmoid into the peritoneal cavity to incite

inflammation and consequent faecal peritonitis.

Occasionally the omentum can also surround and

wall off focal inflammation to prevent extension of

the inflammation to involve the rest of the peritoneal

cavity, as may be seen in the formation of phlegmon

or an abscess in ruptured acute peritonitis.

We present a rare but clinically important case

of delayed perforation of the bowel by Tenckhoff

catheter. According to this case report and several

reported cases, regular flushing of the dialysis

catheter and early removal if not in use (dysfunctional

or not required) may help prevent this complication.

Declaration

No conflicts of interest were declared by the authors.

References

1. Kagan A, Bar-Khayim Y. Delayed decubitus perforation of

the bowel is a sword of damocles in patients on peritoneal

dialysis [Letter]. Nephron 1996;74:232-3. Crossref

2. Brady HR, Abraham G, Oreopoulos DG, et al. Bowel

erosion due to a dormant peritoneal catheter in

immunosuppressed renal transplant recipients. Perit Dial

Int 1988;8:163-5.

3. Rambausek M, Zeier M, Weinreich T, Ritz E, Rau J, Pomer

S. Bowel perforation with unused Tenckhoff catheters.

Perit Dial Int 1989;9:82.

4. Parvin SD, Beaman M. Ileal erosion by the Tenckhoff

catheter. Perit Dial Bull 1985;5:82.

5. Valles M, Cantarell C, Vila J, et al. Delayed perforation

of the colon by a Tenckhoff catheter. Perit Dial Bull 1982;2:190.

6. Thibodeaux LC. Bowel perforation associated with

continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Nephron

1995;70:265. Crossref

7. Saweirs WW, Casey J. Asymptomatic bowel perforation by

a Tenckhoff catheter. Perit Dial Int 2005;25:195-6.

8. Balaji V, Digard N, Wise MH. Delayed bowel erosion due

to functioning chronic ambulatory peritoneal dialysis

catheter. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1996;11:368-9. Crossref