DOI: 10.12809/hkmj144362

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Primary gestational choriocarcinoma of the

vagina: magnetic resonance imaging findings

T Wong, FRCR; Eliza PY Fung, FHKCR, FHKAM (Radiology); Alfred WT Yung, FHKCR, FHKAM (Radiology)

Department of Radiology, Princess Margaret Hospital, Laichikok, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr T Wong (gloria_wong@live.com)

Case report

A 33-year-old nulligravid Filipino woman was

admitted to the gynaecology ward of Princess

Margaret Hospital in April 2014, with lower

abdominal pain and recurrent retention of urine. Her

pregnancy test was positive. Per-vaginal examination

revealed a 4-cm firm, fixed, and wide-based vaginal

mass with smooth wall over the upper anterior

vagina. Bedside transabdominal ultrasonography

confirmed a 4.5-cm solid mass in the anterior vagina

and a 3.5-cm intramural fibroid over the left side

of the uterus. No adnexal mass or free fluid was

seen. Beta human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG)

level was elevated to 270 743 IU/L (reference level,

<5.0 IU/L for non-pregnant women), and repeated

checking 3 days later was 253 957 IU/L. Alpha-fetoprotein,

carcinoembryonic antigen, and Ca-125

were negative. A urologist was consulted and the

patient underwent flexible cystoscopy that revealed

indentation of the urinary bladder by an external

mass. Mild erythematous changes were visualised

at the right urinary bladder base. Biopsy revealed

inflammation but no malignant cells.

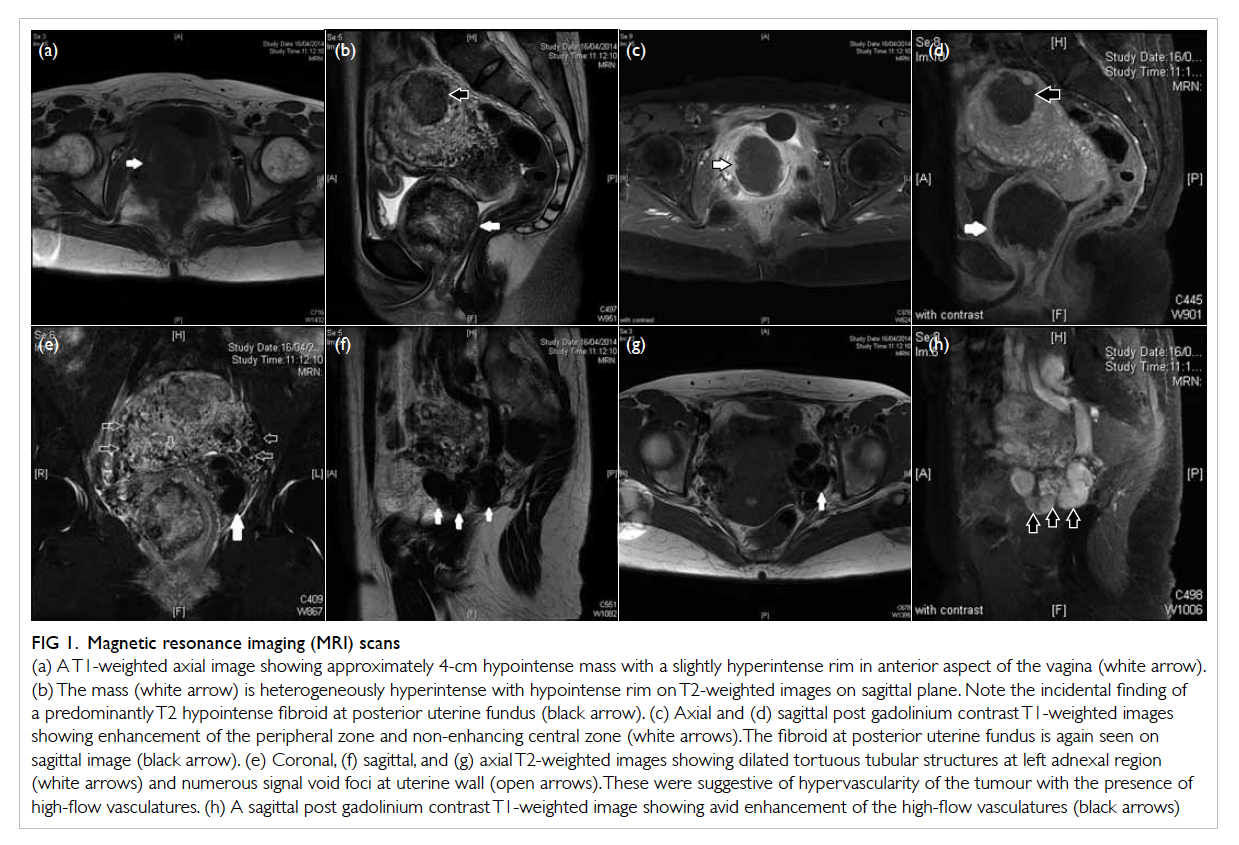

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the

pelvis revealed a 4.8 cm x 5.2 cm x 4 cm (craniocaudal

x anteroposterior x transverse) mass located at the

anterior aspect of the vagina. It was hypointense

with a faint hyperintense rim on T1-weighted

images (Fig 1a) and heterogeneously hyperintense

with hypointense rim on T2-weighted images (Fig 1b). Peripheral enhancement was observed while the

central part remained non-enhanced (Figs 1c and 1d). Part of the mass closely abutted the cervix and

urinary bladder, where intervening fat planes could

not be well-delineated. The urinary bladder wall was

trabeculated. Dilated enhancing tortuous tubular

structures were seen at the left adnexal region and

numerous signal void foci were observed at the

uterine wall. These were due to the presence of high-flow

vasculatures related to tumour hypervascularity

(Figs 1e to 1h). There was also an incidental finding

of a predominantly T2 hypointense non-enhancing

intramural fibroid at the posterior uterine fundus

(Figs 1b and 1d). No ovarian mass was detected and

no intra-uterine gestational sac or ectopic pregnancy.

Figure 1. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans

(a) A T1-weighted axial image showing approximately 4-cm hypointense mass with a slightly hyperintense rim in anterior aspect of the vagina (white arrow). (b) The mass (white arrow) is heterogeneously hyperintense with hypointense rim on T2-weighted images on sagittal plane. Note the incidental finding of a predominantly T2 hypointense fibroid at posterior uterine fundus (black arrow). (c) Axial and (d) sagittal post gadolinium contrast T1-weighted images showing enhancement of the peripheral zone and non-enhancing central zone (white arrows). The fibroid at posterior uterine fundus is again seen on sagittal image (black arrow). (e) Coronal, (f) sagittal, and (g) axial T2-weighted images showing dilated tortuous tubular structures at left adnexal region (white arrows) and numerous signal void foci at uterine wall (open arrows). These were suggestive of hypervascularity of the tumour with the presence of high-flow vasculatures. (h) A sagittal post gadolinium contrast T1-weighted image showing avid enhancement of the high-flow vasculatures (black arrows)

Later examination under anaesthesia

revealed that the lower part of the vaginal lesion

had ruptured. Excision of part of the vaginal lesion

was performed. Tissue frozen section confirmed

it to be choriocarcinoma with no other germ cell

component. DNA polymorphism analysis was

performed in a microsatellite analysis using six

markers by extracting DNA from the microdissected

tumour cells, then comparing it with normal DNA

extracted from a peripheral blood sample. The result

favoured gestational choriocarcinoma. In addition,

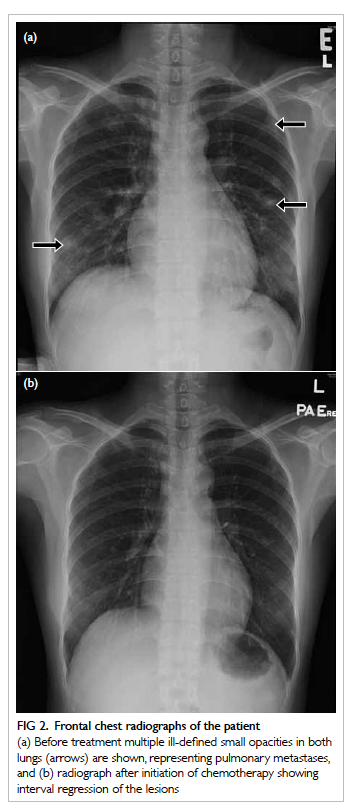

chest X-ray revealed multiple ill-defined opacities in

both lungs, measuring about 0.8 to 1.2 cm in size (Fig 2a).

Figure 2. Frontal chest radiographs of the patient

(a) Before treatment multiple ill-defined small opacities in both lungs (arrows) are shown, representing pulmonary metastases, and (b) radiograph after initiation of chemotherapy showing interval regression of the lesions

The patient was diagnosed with primary

gestational choriocarcinoma of the vagina with

lung metastases, and suspicious infiltration of

the urinary bladder and cervix. She was further

managed at the gynae-oncology specialist centre

and given chemotherapy (etoposide, methotrexate,

actinomycin, and cisplatinum). The β-hCG level

dropped to 5604 IU/L with interval regression of the

pulmonary nodules after initiation of chemotherapy

(Fig 2b).

Discussion

Gestational trophoblastic disease comprises

a wide spectrum of benign/premalignant to

malignant conditions and includes hydatidiform

mole (complete or partial), invasive mole,

choriocarcinoma, and placental-site trophoblastic

tumour. The incidence varies in different countries

with the highest rate noted in South-East Asia. The

cause of such variation is not well understood.1

Choriocarcinoma is a malignant form of gestational

trophoblastic neoplasia, and generally arises in

the uterine corpus of women of reproductive age

with coincident or antecedent pregnancy. Primary

extrauterine choriocarcinoma is rare and most

reported cases have occurred in the uterine cervix.2

It is thought to arise along the path of migration

of germ cells to gonads, or de-differentiated from

another histological type.3 Our case was very unusual

as it occurred in the vagina. The most common site

of metastasis for choriocarcinoma is lung,1 and this

also occurred in our patient.

The clinical diagnosis of extrauterine

choriocarcinoma is extremely difficult as symptoms

are often non-specific. Vaginal bleeding is the

most common presenting symptom,2 but as such

often mimics other more common disease entities.

Primary extrauterine choriocarcinoma has been

misdiagnosed as ectopic pregnancy,2 4 dysfunctional

uterine haemorrhage,5 and cervical polyp.6 This can

often lead to a delay in proper management. Since

trophoblastic neoplasm such as choriocarcinoma

produces an excessive amount of β-hCG, serial

monitoring of its trend is very helpful for diagnosis

and follow-up of treatment response. The mainstay

of treatment is chemotherapy, as choriocarcinoma

is highly chemosensitive.2 For a nulligravid woman

as in this case, differentiation between gestational

or non-gestational origin merely from a clinical

history can be confusing. Differentiation by DNA

polymorphism analysis is useful to guide the

management as non-gestational choriocarcinoma is

known to have a worse prognosis and to be resistant

to single-agent chemotherapy.7

To the best of our knowledge, the imaging

findings of primary extrauterine choriocarcinoma

are rarely described in the literature, particularly

that of vaginal origin. In the present case, MRI

showed a hypointense vaginal tumour with

hyperintense rim on T1-weighted images and

heterogeneously hyperintense with hypointense

rim on T2-weighted images. Rim enhancement was

observed on T1-weight images after gadolinium

contrast injection. The non-enhancing centre of the

tumour could be due to tumour necrosis, commonly

seen in choriocarcinoma. Poor delineation of fat

planes with cervix and urinary bladder raised the

suspicion of tumour involvement. Features of

chronic bladder outlet obstruction were present

as suggested by the trabeculated bladder outline.

The signal void foci over the uterine wall and the

high-flow vasculatures at the left adnexal region

signified angiogenesis and neovascularisation, thus

the hypervascular nature of the tumour.1 This is in

accordance with the characteristic hypervascularity

of choriocarcinoma.5 6 The multiple nodular

opacities on chest X-ray most likely represented lung

metastases, although histological confirmation was

not performed. Interval shrinkage of these nodules

was observed on chest X-ray following initiation of

treatment.

In summary, imaging findings of a

hypervascular tumour and exceedingly high levels

of β-hCG are useful in making the diagnosis of

extrauterine choriocarcinoma, and MRI is valuable

in assessing extrauterine extension, tumour

vascularity, and overall staging of the tumour.

References

1. Allen SD, Lim AK, Seckl MJ, Blunt DM, Mitchell AW.

Radiology of gestational trophoblastic neoplasia. Clin

Radiol 2006;61:301-13. Crossref

2. Kairi-Vassilatou E, Papakonstantinou K, Grapsa D,

Kondi-Paphiti A, Hasiakos D. Primary gestational

choriocarcinoma of the uterine cervix. Report of a case and

review of the literature. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2007;17:921-5. Crossref

3. Dilek S, Pata O, Tok E, Polat A. Extraovarian nongestational

choriocarcinoma in a postmenopausal woman. Int J

Gynecol Cancer 2004;14:1033-5. Crossref

4. Gerson RF, Lee EY, Gorman E. Primary extrauterine

ovarian choriocarcinoma mistaken for ectopic pregnancy:

sonographic imaging findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol

2007;189:W280-3. Crossref

5. Maestá I, Michelin OC, Traiman P, Hokama P, Rudge MV.

Primary non-gestational choriocarcinoma of the uterine

cervix: a case report. Gynecol Oncol 2005;98:146-50. Crossref

6. Yahata T, Kodama S, Kase H, et al. Primary choriocarcinoma

of the uterine cervix: clinical, MRI, and color Doppler

ultrasonographic study. Gynecol Oncol 1997;64:274-8. Crossref

7. Koo HL, Choi J, Kim KR, Kim JH. Pure non-gestational

choriocarcinoma of the ovary diagnosed by DNA

polymorphism analysis. Pathol Int 2006;56:613-6. Crossref