Hong Kong Med J 2016 Apr;22(2):131–7 | Epub 12 Feb 2016

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj154595

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Participant evaluation of simulation training using crew resource management in a hospital setting in Hong Kong

Christina KW Chan, BSc, MPH1;

Eric HK So, FHKCA, FHKAM (Anaesthesiology)2;

George WY Ng, FHKCP, FHKAM (Medicine)3;

Teresa WL Ma, FRCOG, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)4;

Karen KL Chan, FHKCEM, FHKAM (Emergency Medicine)5;

LY Ho, FRCS (Urology), FHKAM (Surgery)1

1 Multidisciplinary Simulation and Skills Centre, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Jordan, Hong Kong

2 Anaesthesiology and Operating Theatre Services, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Jordan, Hong Kong

3 Intensive Care Unit, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Jordan, Hong Kong

4 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Jordan, Hong Kong

5 Accident and Emergency Department, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Jordan, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Ms Christina KW Chan (mdssc_research@ha.org.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: A simulation team–based crew

resource management training programme was

developed to provide a unique multidisciplinary

learning experience for health care professionals in

a regional hospital in Hong Kong. In this study, we

evaluated how health care professionals perceive the

programme.

Methods: A cross-sectional questionnaire survey

was conducted in the Multidisciplinary Simulation

and Skills Centre at Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Hong

Kong. A total of 55 individuals in the departments of

Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Anaesthesiology and

Operating Theatre Services, Intensive Care Unit,

and Accident and Emergency participated in the study between

June 2013 and December 2013. The course content

was specially designed according to the needs of

the clinical departments and comprised a lecture

followed by scenarios and debriefing sessions.

Principles of crew resource management were

introduced and taught throughout the course by

trained instructors. Upon completion of each course,

the participants were surveyed using a 5-point Likert

scale and open-ended questions.

Results: The participant’s responses to the survey

were related to course organisation and satisfaction,

realism, debriefing, and relevance to practice.

The overall rating of the training programme was

high, with mean Likert scale scores of 4.1 to 4.3.

The key learning points were identified as closed-loop

communication skills, assertiveness, decision

making, and situational awareness.

Conclusions: The use of a crew resource

management simulation-based training programme

is a valuable teaching tool for frontline health care

staff. Concepts of crew resource management were

relevant to clinical practice. It is a highly rated

training programme and our results support its

broader application in Hong Kong.

New knowledge added by this study

- Our data support the use of crew resource management (CRM) in a simulation-based training programme as an effective means for teaching health care professionals in a public hospital setting in Hong Kong. Programmes may need to be customised for each specialty, however. Our results showed that this type of training is highly rated and accepted by frontline health care professionals.

- A key area for future improvement in health care providers is to teach and practise CRM. CRM has been recognised as an effective educational tool in health care organisations. Its broader application in Hong Kong should be encouraged.

Introduction

Simulation-based training is increasingly recognised

as a useful educational tool in health care

organisations.1 Within an acute care setting, these

tools are used for various training purposes, for

example, teaching technical2 and non-technical3 4

skills and rehearsing rare events.5 Simulation is

a technique “to replace or amplify real [patient]

experiences with guided experiences that evoke or

replicate substantial aspects of the real world in a

fully interactive manner”.6 With the application of

adult learning theory,7 simulation-based training

is usually designed to resemble the reality and

allows trainees to acquire knowledge, skills, and

competence in a safe and controlled environment.8 9

Studies have shown that teamwork plays an

important role in the prevention of adverse events

and errors.10 11 Simulation-based training programmes

that focus on crew resource management (CRM)

criteria have been found to effectively improve

teamwork skills. Such criteria emphasise teaching

of non-technical skills, such as communication,

leadership, assertiveness, and situational awareness,

thereby improving patient safety.12 13

Crew resource management is a risk-reduction

programme of the Hospital Authority (HA) in Hong

Kong and has run since 2009. Between 2009 and

2012, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital

piloted the classroom-based CRM programme

to approximately 2000 staff in the hospital.14 The

programme received positive feedback from staff

and the impact on patient safety was evident in the

programme evaluation. Thus, the HA decided that

a second-phase roll-out of CRM was necessary

because there was a need for team-based training.

Queen Elizabeth Hospital (QEH) and Tuen Mun

Hospital were the two public hospitals selected to

implement the second pilot programme of the CRM

focusing on specialty-based simulation training.

The Multidisciplinary Simulation and

Skills Centre (MDSSC) at QEH has developed a

simulation team–based CRM training programme.

This new training programme provides a unique

multidisciplinary learning experience for health

care professionals at QEH. The MDSSC used this

opportunity to evaluate how health care professionals

perceive the programme.

Methods

The train-the-trainer workshop

In order to roll out the second phase of the CRM

programme to QEH, HA engaged Safer Healthcare15

to advise on the development and delivery of CRM

training courses. A 3-day on-site CRM train-the-trainer

workshop was held at MDSSC between

March and April 2013. The workshop was intended

for doctors and nurses working at QEH who were

interested in teaching medical education and would

like to become a CRM-certified trainer. All workshops

were taught by experienced instructors from Safer

Healthcare.15 The content of the workshops included

reviewing the use of CRM in health care, delivering

the CRM principles, enhancing presentation skills,

and handling difficulties and challenges in team

debriefing. All trainees had the unique opportunity

to develop scenarios using CRM principles. A total

of 40 doctors and nurses were trained and certified

to teach CRM courses.

Curriculum design

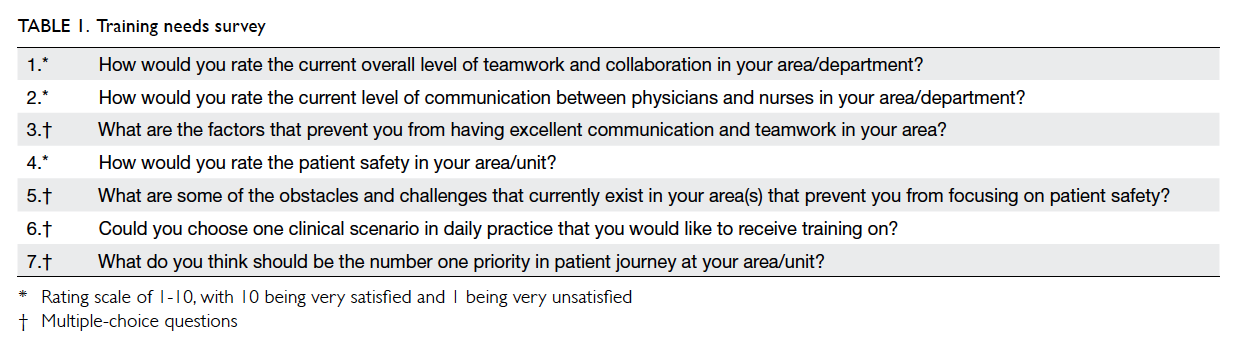

In order to determine the components of CRM

training most appropriate for frontline health

care staff, a survey was conducted of all frontline

health care staff in four selected high-risk areas

where teamwork is essential for satisfactory patient

outcome: Obstetrics and Gynaecology (O&G),

Anaesthesiology and Operating Theatre Services

(Anaes & OTS), Intensive Care Unit (ICU), and

Accident and Emergency (A&E). The survey was

designed to assess staff perception of teamwork and

patient safety, obstacles, and challenges encountered

in the workplace, and areas where training was

wanted. Some of the questions were based on the most

common reasons why medical errors occur among

the four specialties as well as from the literature.16 17 18 The survey consisted of seven multiple-choice and

rating-scale questions about teamwork, patient

safety, the obstacles and challenges in practice, and

training needs (Table 1).

The CRM curriculum for the four specialties

was first proposed by the course coordinators who

were the specialist consultants and associate consultants

from respective departments at QEH. The

course coordinators first identified their staffing needs

based on the results of the survey. They developed a

specialty-based training programme that addressed

their frontline staff learning needs and was related

to the type of sentinel and serious untoward events

reported. This would enable participants to learn

non-technical CRM skills and apply them in their

workplace when making clinical judgements and

performing procedures. The specialty-based training

programme comprised three components: a lecture,

games, and scenarios. Each scenario was customised

for each specialty in order to fulfil its learning

objectives, specific educational outcomes, and needs

of the department in order to enhance participants’

learning experience. All scenario practice sessions

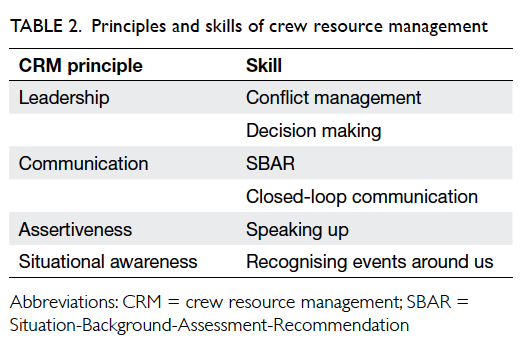

included CRM principles as defined in Table 2 and were chosen according to the needs at QEH.

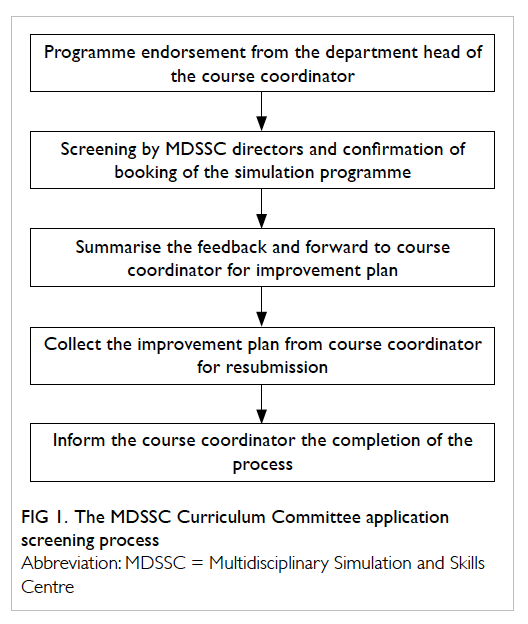

After the programmes had been endorsed

by the department head, the directors of MDSSC

reviewed and evaluated the programme. Feedback

and recommendations were given to course

coordinators so they could improve the quality of

the training, and ensure CRM components were

included and that the course supported the MDSSC’s

mission statement. The course coordinators made

changes according to the reviewers’ comments.

A confirmation of the booking date was given to

the course coordinators once the programme had

been endorsed by the reviewers. The evaluation of

a programme required approximately 2 weeks to

complete (Fig 1).

The training programme

The CRM training programme took place between

June and December 2013. The training began with

a lecture introducing the background of CRM. A

game was played afterwards and served as an ‘icebreaker’

and illustrated the importance of teamwork,

leadership, and decision making.

Next, simulation training was conducted with

two scenarios followed by a debriefing session.

Each scenario was performed by a group of four

to five health care frontline staff. Members of each

group participated in the debriefing after each

simulation scenario. The role of the trainer was to

lead a discussion about team strengths and areas for

improvement. This allowed participants to reflect on

their experience related to CRM skills and clinical

knowledge in the scenarios. Participants may also

have learnt new concepts and techniques that could

be applied in daily practice. All training was given

at MDSSC and conducted by experienced certified

CRM trainers.

Sample

Participants were recruited from four high-risk

departments at QEH through nominations based

on their availability. The study sample included

doctors and nurses working in the frontline area

of these four departments: O&G, Anaes & OTS,

ICU, and A&E. Each participant was assigned a

specific role during each scenario. The role could

be changed for different simulation scenarios. All

participants received the same educational content

and simulation opportunities.

Data collection

Participants evaluated the CRM simulation training

by anonymous completion of a questionnaire

that comprised six open-ended questions and 14

questions that were answered on a 5-point Likert

scale (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 =

neutral, 4 = agree, 5 = strongly agree). Open-ended

questions focused on the areas of learning needs,

the specific areas where CRM can be implemented,

the learning points that were applicable to practice,

and recommendation of the programme to other

colleagues. The first section aimed to obtain

information about the training programme. The

open-ended questions were asked to elicit qualitative

responses related to learning and demographic

information. The evaluation was paper-based and

completed by participants at the end of the training

programme.

Statistical analysis

The data were tabulated using Microsoft Excel

and analysed using the STATA 13. Demographic

information of participants was reported as

frequency (%) and participant scores were reported

as mean ± standard deviation.

Results

Training needs analysis

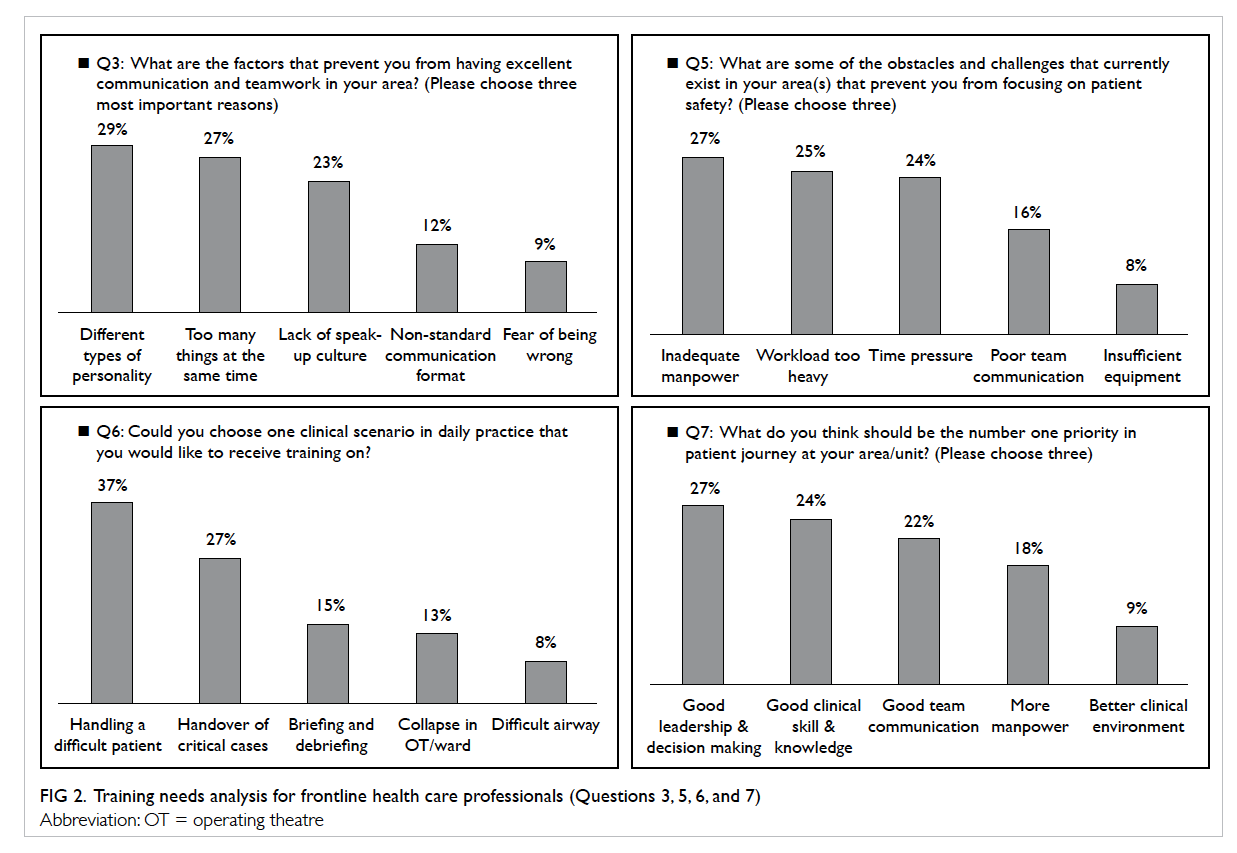

A total of 380 frontline health care staff were invited

to participate in the training needs survey that was

completed by 319 (84%). The mean satisfaction rating

on a scale of 1 to 10 for overall level of teamwork and

collaboration, the current level of communication

between physicians and nurses, and patient safety on

their unit was 6.5, 6.2, and 7.1, respectively. Factors

that prevented frontline health care staff from

achieving excellent communication and teamwork

included different types of personality among

colleagues (n=92, 29%), too many things to attend to

at the same time (n=85, 27%), a culture that prevented

an individual from speaking out (n=73, 23%), lack of

a standard communication format (n=39, 12%), and

fear of being wrong (n=30, 9%). The obstacles and

challenges that prevented them from focusing on

patient safety included inadequate manpower (n=85,

27%), heavy workload (n=80, 25%), time pressure

(n=77, 24%), poor team communication (n=51, 16%),

and insufficient equipment (n=26, 8%). The top five

areas in which staff would like to receive training were

handling a difficult patient (n=118, 37%), handover

of critical cases (n=85, 27%), briefing and debriefing

(n=48, 15%), collapse in the operating theatre/ward

(n=42, 13%), and difficult airway (n=26, 8%). Good

leadership and decision making was considered by

86 (27%) of staff to be the top priority in patient care,

followed by good clinical skill and knowledge (n=78,

24%), good team communication (n=69, 22%),

more manpower (n=57, 18%), and better clinical

environment (n=29, 9%) [Fig 2].

Figure 2. Training needs analysis for frontline health care professionals (Questions 3, 5, 6, and 7)

The training programme

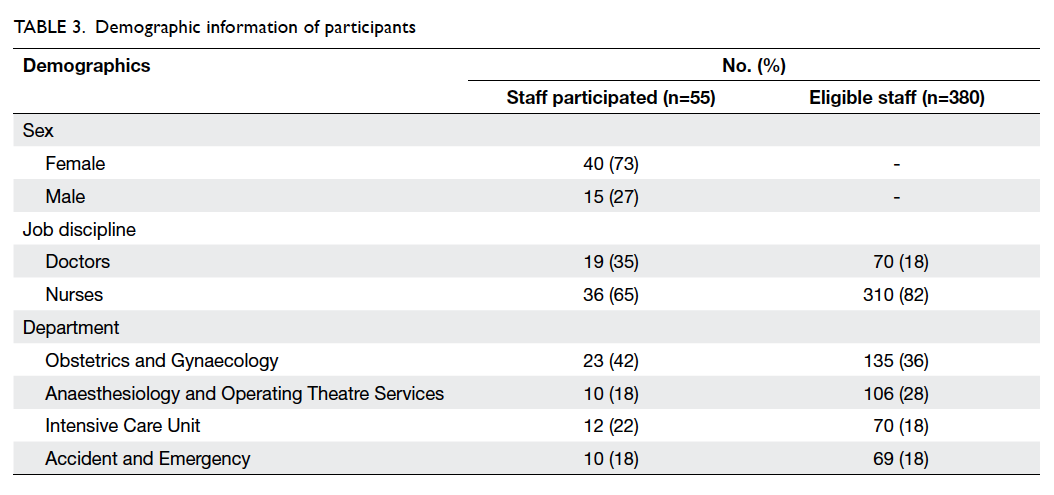

The number of frontline health care staff eligible for

the study in the O&G, Anaes & OTS, ICU, and A&E

departments was 135, 106, 70, and 69, respectively.

Among them, 55 (of whom 40 were female and

36 were nurses) were nominated to participate in

the study and completed the simulation training

programme. They included 23 participants from

O&G, 10 from Anaes & OTS, 12 from ICU, and 10

from A&E. The characteristics of these participants

are summarised in Table 3.

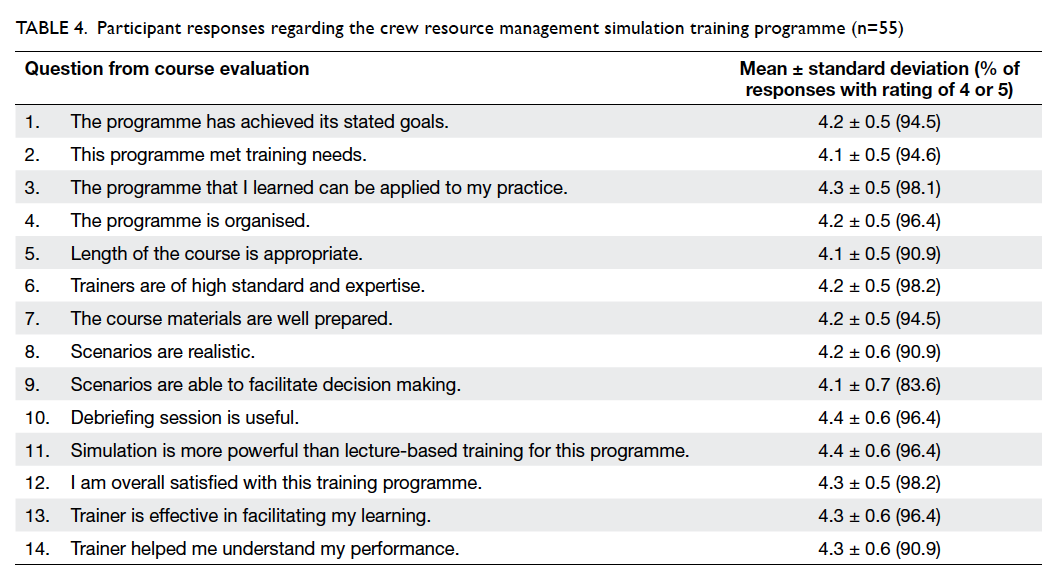

Likert-scale questions

Participant responses to the Likert-scale questions

were very positive, with mean scores of 4.1 to 4.3.

Almost all participants responded positively with

either ‘strongly agree’ or ‘agree’ to questions about

overall satisfaction with the training programme, the

applicability of the programme to area of practice,

and high standard and expertise of the trainers.

The question that received the lowest mean rating

was related to the ability of scenarios to facilitate

decision making. Nonetheless this question was still

considered ‘agree’ on a scale of 1 (strongly disagree)

to 5 (strongly agree). None of the questions were

rated ‘disagree’ or ‘strongly disagree’. Participant

ratings for all 14 questions are summarised in Table 4.

Table 4. Participant responses regarding the crew resource management simulation training programme (n=55)

Open-ended questions

For the open-ended questions, 85% (47/55) of

participants stated that they would recommend the

programme to other colleagues and 15% did not

respond to this question. Of the 55 participants, 11

commented on learning more about closed-loop

communication, situational awareness, assertiveness,

conflict resolution, decision making, and leadership.

Six participants commented positively on the

course itself. Specifically, comments were related to CRM

elements: “the CRM training is very useful to our

clinical work and even to our daily life” and “the

CRM videos are funny and useful”. The remaining

comments were “good”, “a pleasant experience”, and

“the programme was useful”.

When asked to list the learning points applicable

to work, participants most commonly responded

to the CRM elements, such as communication skills,

assertiveness, decision making, and situational

awareness.

Discussion

Training in non-technical skills is essential for health

care professionals to enhance patient safety and

teamwork.19 Hospital patients are normally treated

by a team having various disciplines; therefore, team

training is important to prevent human error.

High realism simulation is becoming widely

used in health care education.20 21 22 23 It creates a realistic

risk-free environment for learners to practise and

improve confidence in life-saving skills.

In our study, frontline health care staff

surveyed at MDSSC reacted positively to their initial

experience with CRM training, suggesting that this is

a favourable means by which to provide simulation-based

training. Almost all participants (91%-98%)

rated their level of agreement as high or very high for

overall course organisation, course content, trainer

performance, programme satisfaction, training

needs, and the usefulness of debriefing session.

These findings indicate that simulation-based CRM

training was well accepted by frontline health care

staff and they would likely benefit from simulation-based

scenarios, and is consistent with a previous

study.24

A number of participants stated that they would

recommend the programme to other colleagues.

Participants made very positive comments about

the CRM simulation-based training programme

and perceived CRM as an important means to

improve their teamwork skills. Although CRM can

be taught in a didactic approach, we believe that a

simulation approach has the advantage of motivating

participants to learn about teamwork skills and to

alter their behaviour, so reducing the risk of adverse

events. This type of training will help health care

professionals incorporate the CRM principles into

their daily practice.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to

specifically address the use of CRM in a tailor-made

specialty-based simulation training programme in

multiple clinical departments in a public hospital

in Hong Kong. Prior to this study, we distributed a

training needs survey to all frontline staff among the

four specialties that asked about their perception

of teamwork and learning needs. The results from

this survey provided a clear idea about the design

of scenarios. The topics and content were also

appropriate and could contribute to the development

of teamwork in a health care organisation. In terms

of teaching quality, all instructors were certified and

had completed the same CRM train-the-trainer

programme, thus teaching methods were consistent.

There are several limitations to this study.

First, it was undertaken in a single hospital

and analysed a simulation-based CRM training

programme specifically designed for each specialty.

Its generalisation to other CRM simulation-based

programmes in other multidisciplinary settings

may be limited. Second, the sample size was small.

Nonetheless this pilot study was designed to

determine staff perception of learning CRM rather

than to demonstrate efficacy. Furthermore, the

participants were recruited through nomination.

It is unclear whether those who were nominated

to participate may differ to those who were not

nominated (in terms of their characteristics). The

results may reflect a possible selection bias as

participants may be more inclined to participate

and learn from such a training programme. Other

limitations include the training needs survey that

was a self-report, not an objective assessment, and

was limited to the categories included in the survey.

The optional “other” response was rarely used by the

participants, however. Finally, although the survey

demonstrated a high level of acceptance of and

satisfaction with simulation-based CRM training,

this does not necessarily translate into improved

frontline health care performance. Further research

in this area is needed.

Conclusions

We have developed and rolled out a specialty-based

simulation CRM training programme in a

public hospital setting in Hong Kong. Our findings

demonstrate that CRM appeared to be highly valued

by participants and was applicable to their daily

practice. It also demonstrated that training needs

analysis may be useful to develop the content of a

simulation CRM training programme. The culture

of patient safety needs time to change however, and

this programme is just the first step in developing a

safety culture in health care organisations.

Acknowledgements

The MDSSC team would like to express its gratitude

to HA Head Office for their support and contribution

in this study. Without their support, the study could

not have been completed.

References

1. Cook DA, Hatala R, Brydges R, et al. Technology-enhanced

simulation for health professions education: a systematic

review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2011;306:978-88. Crossref

2. Boet S, Bould MD, Schaeffer R, et al. Learning fibreoptic

intubation with a virtual computer program transfers to

‘hands on’ improvement. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2010;27:31-5. Crossref

3. Yee B, Naik VN, Joo HS, et al. Nontechnical skills in

anesthesia crisis management with repeated exposure to

simulation-based education. Anesthesiology 2005;103:241-8. Crossref

4. Kneebone R, Nestel D, Wetzel C, et al. The human face of

simulation: patient-focused simulation training. Acad Med

2006;81:919-24. Crossref

5. Decarlo D, Collingridge DS, Grant C, Ventre KM. Factors

influencing nurses’ attitudes toward simulation-based

education. Simul Healthc 2008;3:90-6. Crossref

6. Gaba DM. The future vision of simulation in healthcare.

Simul Healthc 2007;2:126-35. Crossref

7. Speck M. Best practice in professional development for

sustained educational change. ERS Spectr 1996;14:33-41.

8. Kneebone RL, Scott W, Darzi A, Horrocks M. Simulation

and clinical practice: strengthening the relationship. Med

Educ 2004;38:1095-102. Crossref

9. Ziv A, Wolpe PR, Small SD, Glick S. Simulation-based

medical education: an ethical imperative. Simul Healthc

2006;1:252-6. Crossref

10. Manser T. Teamwork and patient safety in dynamic

domains of healthcare: a review of the literature. Acta

Anaesthesiol Scand 2009;53:143-51. Crossref

11. Künzle B, Kolbe M, Grote G. Ensuring patient safety

through effective leadership behaviour: a literature review.

Saf Sci 2010;48:1-17. Crossref

12. Kosnik LK. The new paradigm of crew resource

management: just what is needed to re-engage the

stalled collaborative movement? Jt Comm J Qual Improv

2002;28:235-41.

13. Risser DT, Rice MM, Salisbury ML, Simon R, Jay GD,

Berns SD. The potential for improved teamwork to

reduce medical errors in the emergency department.

The MedTeams Research Consortium. Ann Emerg Med

1999;34:373-83. Crossref

14. Hospital Authority Quality and Risk Management. Annual

Report (2012-2013). Hong Kong: Hospital Authority; 2013:

10-1.

15. Marshall DA, Manus DA. A team training program

using human factors to enhance patient safety. AORN J

2007;86:994-1011. Crossref

16. O’Daniel M, Rosenstein AH. Professional communication

and team collaboration. In: Hughes RG, editor. Patient

safety and quality: an evidence-based handbook for nurses.

Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and

Quality (US); 2008.

17. Leonard M, Graham S, Bonacum D. The human factor:

the critical importance of effective teamwork and

communication in providing safe care. Qual Saf Health

Care 2004;13 Suppl 1:i85-90. Crossref

18. Manojlovich M, Antonakos CL, Ronis DL. Intensive care

units, communication between nurses and physicians, and

patients’ outcomes. Am J Crit Care 2009;18:21-30. Crossref

19. Gordon M, Darbyshire D, Baker P. Non-technical skills

training to enhance patient safety: a systematic review.

Med Educ 2012;46:1042-54. Crossref

20. Bruppacher HR, Alam SK, LeBlanc VR, et al. Simulation-based

training improves physicians’ performance in patient

care in high-stakes clinical setting of cardiac surgery.

Anesthesiology 2010;112:985-92. Crossref

21. Burkhart HM, Riley JB, Hendrickson SE, et al. The

successful application of simulation-based training in

thoracic surgery residency. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg

2010;139:707-12. Crossref

22. Sexton JB, Makary MA, Tersigni AR, et al. Teamwork

in the operating room: frontline perspectives among

hospitals and operating room personnel. Anesthesiology

2006;105:877-84. Crossref

23. Seymour NE, Gallagher AG, Roman SA, et al. Virtual

reality training improves operating room performance:

results of a randomized, double-blinded study. Ann Surg

2002;236:458-63; discussion 63-4. Crossref

24. Blum RH, Raemer DB, Carroll JS, Sunder N, Felstein

DM, Cooper JB. Crisis resource management training

for an anaesthesia faculty: a new approach to continuing

education. Med Educ 2004;38:45-55. Crossref