Hong Kong Med J 2016 Apr;22(2):124–30 | Epub 11 Mar 2016

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj154706

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE CME

Mushroom poisoning in Hong Kong: a ten-year review

CK Chan, Dip Clin Tox (HKPIC & HKCEM), FHKAM (Emergency Medicine)1;

HC Lam, Dip Clin Tox (HKPIC & HKCEM), FHKAM (Emergency Medicine)1;

SW Chiu, MPhil (Biology), PhD2;

ML Tse, FHKCEM, FHKAM (Emergency Medicine)1;

FL Lau, FRCSEd, FHKAM (Emergency Medicine)1

1 Hong Kong Poison Information Centre, United Christian Hospital, Kwun

Tong, Hong Kong

2 School of Life Sciences, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin,

Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr CK Chan (chanck3@ha.org.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: Mushroom poisoning is a cause of

major mortality and morbidity all over the world.

Although Hong Kong people consume a lot of

mushrooms, there are only a few clinical studies and

reviews of local mushroom poisoning. This study

aimed to review the clinical characteristics, source,

and outcome of mushroom poisoning incidences in

Hong Kong.

Methods: This descriptive case series review was

conducted by the Hong Kong Poison Information

Centre and involved all cases of mushroom poisoning

reported to the Centre from 1 July 2005 to 30 June

2015.

Results: Overall, 67 cases of mushroom poisoning

were reported. Of these, 60 (90%) cases presented

with gastrointestinal symptoms of vomiting,

diarrhoea, and abdominal pain. Gastrointestinal

symptoms were early onset (<6 hours post-ingestion)

and not severe in 53 patients and all recovered after

symptomatic treatment and a short duration of

hospital care. Gastrointestinal symptoms, however,

were of late onset (≥6 hours post-ingestion) in

seven patients; these were life-threatening cases

of amatoxin poisoning. In all cases, the poisonous

mushroom had been picked from the wild. Three

cases were imported from other countries, and four

collected and consumed the amatoxin-containing

mushrooms in Hong Kong. Of the seven cases of

amatoxin poisoning, six were critically ill, of whom

one died and two required liver transplantation.

There was one confirmed case of hallucinogenic

mushroom poisoning caused by Tylopilus nigerrimus

after consumption of a commercial mushroom

product. A number of poisoning incidences involved

the consumption of wild-harvested dried porcini

purchased in the market.

Conclusion: Most cases of mushroom poisoning in

Hong Kong presented with gastrointestinal symptoms

and followed a benign course. Life-threatening

cases of amatoxin poisoning are occasionally seen.

Doctors should consider this diagnosis in patients

who present with gastrointestinal symptoms that

begin 6 hours or more after mushroom consumption.

New knowledge added by this study

- Local epidemiology data of mushroom poisoning presented between 1 July 2005 and 30 June 2015 that include the first case series of amatoxin poisoning in Hong Kong.

- Life-threatening amatoxin poisoning was caused by consumption of Amanita farinosa. This is the first report of this Amanita species in Hong Kong.

- A confirmed case of hallucinogenic mushroom poisoning was caused by imported Tylopilus nigerrimus.

- Public awareness of the high-risk behaviour of consuming self-picked wild mushrooms should be raised.

- A number of poisoning incidents involved the consumption of wild-harvested dried porcini purchased in the market.

- Doctors should suspect amatoxin poisoning in patients who present with gastrointestinal symptoms that begin 6 hours or more after wild mushroom consumption. Hong Kong Poison Information Centre can be consulted early to facilitate urgent mushroom identification and antidote treatment.

Introduction

Mushroom poisoning is a global phenomenon and

can be a source of major mortality and morbidity.

Although Hong Kong people consume a large volume

of mushrooms, there are few clinical studies and

reviews related to local mushroom poisoning.1 2 The

diagnosis of mushroom poisoning should be based

on clinical features, laboratory investigations, and

mushroom identification. Due to the lack of leftover

mushroom samples in most cases, emergency

physicians and clinical toxicologists usually have

to diagnose mushroom poisoning based on clinical

syndromes alone without mushroom identification

by mycologists. Diaz3 has reviewed and established

the classification of mushroom poisoning based on

the time of presentation and target organ systemic

toxicity. With respect to the time of presentation,

mushroom poisoning is categorised as early onset

(<6 hours), late onset (6-24 hours), or delayed onset

(>1 day). Early-onset toxicities include several

neurotoxic, gastrointestinal, and allergic syndromes.

Late-onset toxicities include hepatotoxic,

accelerated nephrotoxic, and erythromelalgia

syndromes. Delayed-onset toxicities include delayed

nephrotoxic, delayed neurotoxic and rhabdomyolytic

syndromes. Syndromic approaches guide earlier

diagnosis and facilitate empirical treatment.3

In Hong Kong, scattered cases of mushroom

poisoning are reported every year. In a report

published by the Centre for Health Protection (CHP),

there were 13 reported cases of wild mushroom

poisoning between January 2002 and May 2005.1

Symptoms occurred 0.5 to 5 hours post-ingestion and

included vomiting (100%), abdominal pain (100%),

diarrhoea (69%), nausea (56%), dizziness (50%),

sweating (37%), numbness (31%), palpitation (19%),

malaise (13%), fever (13%), and headache (6%).2 Of

these patients, seven required hospitalisation and

all of them completely recovered. Individual cases

of mushroom poisoning have been announced in

CHP press releases from time to time. In another

report, seven patients presented with mainly

gastrointestinal symptoms after wild mushroom

consumption between May 2007 and August 2010.2

There have been no reports of life-threatening wild

mushroom poisoning in Hong Kong before this case

series.

Since its establishment in 2005, the Hong

Kong Poison Information Centre (HKPIC) has

provided a 24-hour telephone consultation service

to health care professionals in Hong Kong for poison

information and clinical management advice. We are

actively involved in the diagnosis and management

of mushroom poisoning cases in local hospitals.

Supported by Prof SW Chiu from the School of Life

Sciences of The Chinese University of Hong Kong,

mycological identification can be provided whenever

mushroom samples are available in a poisoning

case. The objectives of this study were to review the

clinical features and mycological identifications in

mushroom poisoning cases recorded by the HKPIC.

Methods

Mushroom poisoning cases recorded by HKPIC

from 1 July 2005 to 30 June 2015 were retrospectively reviewed. Information on patient demographic

details, clinical presentation, sources of mushroom,

investigation results, mycological identification

results, and clinical outcome were obtained.

Descriptive statistics were used for data analysis.

Results

During the 10-year study period, there were 67 cases

of mushroom poisoning. All cases were reported

from hospitals of the Hospital Authority. All patients

were Chinese; 29 (43%) were male and 38 (57%) were

female. The median age was 47 (range, 2-86) years.

Of the 67 cases, 52 (78%) occurred between April and

September when the climate in Hong Kong is optimal

for mushroom growth. In 66 cases, the mushrooms

were intentionally consumed as delicacies. There

was one case of accidental ingestion, in which a

2-year-old boy ingested a wild mushroom in a park.

Ingestion with recreational, suicidal, or malicious

intent was not recorded in this case series.

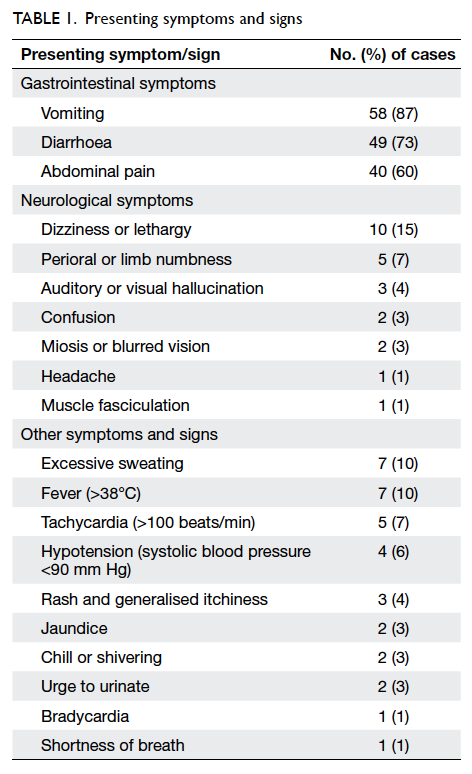

The most common clinical presentation was

gastrointestinal symptoms (Table 1). Symptoms mimicking gastroenteritis were the presenting

feature in 60 (90%) patients. The diagnosis of

these 60 patients included gastroenteritic mushroom

poisoning in 38, cholinergic mushroom poisoning in

five, food poisoning in eight, food allergy in two, and

seven cases of amatoxin poisoning.

Neurological symptoms were also commonly

reported: 20 (30%) patients presented with one or more symptoms

including dizziness, numbness, hallucination,

headache, or confusion (Table 1). Most of them (15

of 20 patients) presented with both neurological and

gastrointestinal symptoms. Four patients presented

with neurological symptoms including visual

hallucinations, dizziness, generalised weakness, and

malaise without gastrointestinal symptoms. They

were subsequently diagnosed with hallucinogenic

mushroom poisoning. One patient presented with

malaise, muscle fasciculation, and profuse sweating

that was diagnosed as cholinergic mushroom

poisoning.

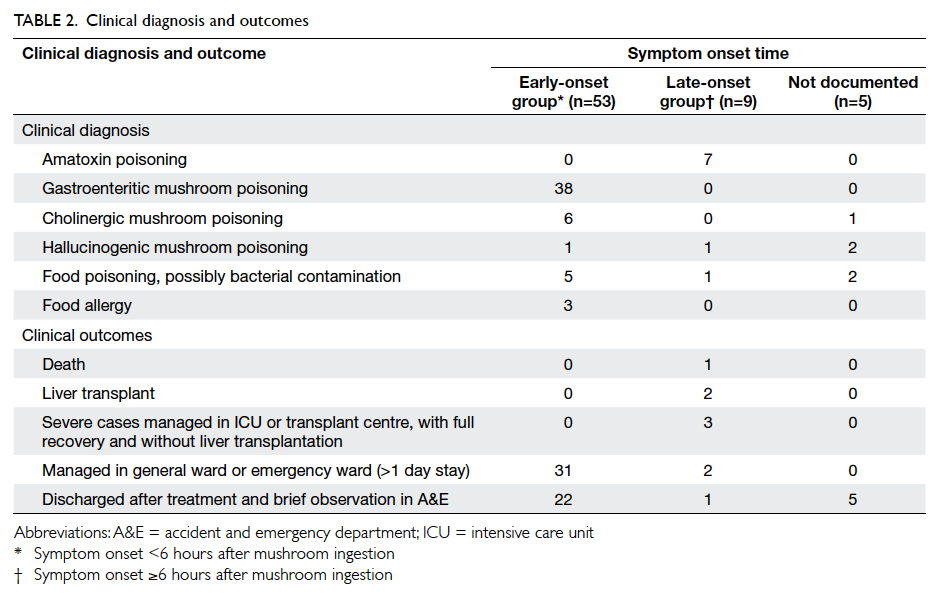

The symptom onset time was documented

in 62 patients (Table 2). Among them, 53 patients developed symptoms within 6 hours of mushroom

consumption (early-onset group). The median

time of symptom onset was 2 hours post-ingestion

(interquartile range [IQR], 2). Most patients (50 out

of 53) presented with early-onset gastrointestinal

symptoms. No severe clinical outcomes were

observed in this group of patients and all recovered

with symptomatic treatment and short duration of

hospital care.

Symptoms developed 6 hours or more after

mushroom consumption in nine patients (late-onset

group). The median time of symptom onset

was 11 hours post-ingestion (IQR, 2). This group

of patients represented potentially life-threatening

mushroom poisoning. All seven cases of amatoxin

poisoning in this case series were found in this

group. The remaining two cases included one case

of hallucinogenic mushroom poisoning caused by

Tylopilus nigerrimus, and one case of food poisoning.

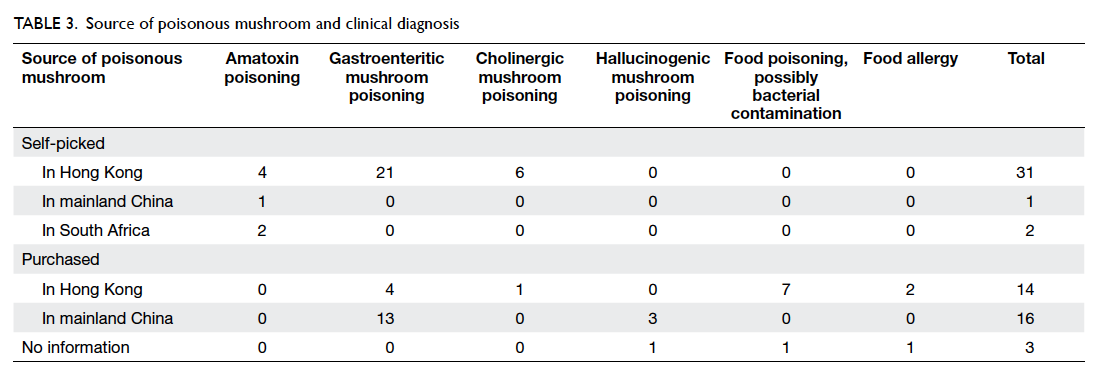

The source of poisonous mushrooms was

documented in 64 cases (Table 3). In 34 (51%) cases, the mushrooms were self-picked from a park,

hillside, or roadside. The locations were usually close

to the patient’s home. On the other hand, 14 (21%)

cases purchased the mushrooms in Hong Kong

and 16 (24%) purchased them in mainland China.

All patients with amatoxin poisoning collected the

mushroom from the wild. The source of mushrooms

was not documented in three (4%) cases.

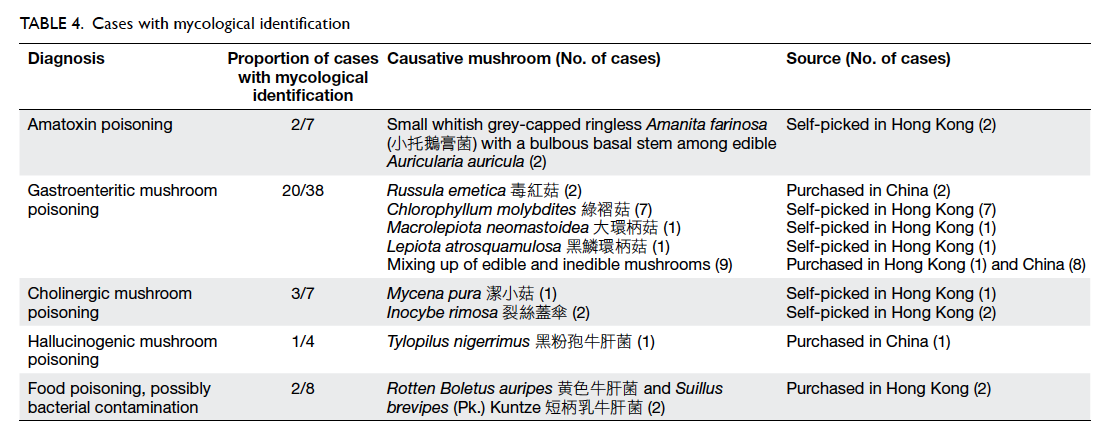

Mycological identification was achieved in 28

cases (Table 4). The diagnosis of amatoxin poisoning

was confirmed by the presence of amatoxin and/or

phallacidin in the urine of five patients.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to describe the pattern

of mushroom poisoning in Hong Kong. Four

mushroom poisoning syndromes, together with food

poisoning and food allergy, were identified to be the

cause of all mushroom poisoning cases in this study.

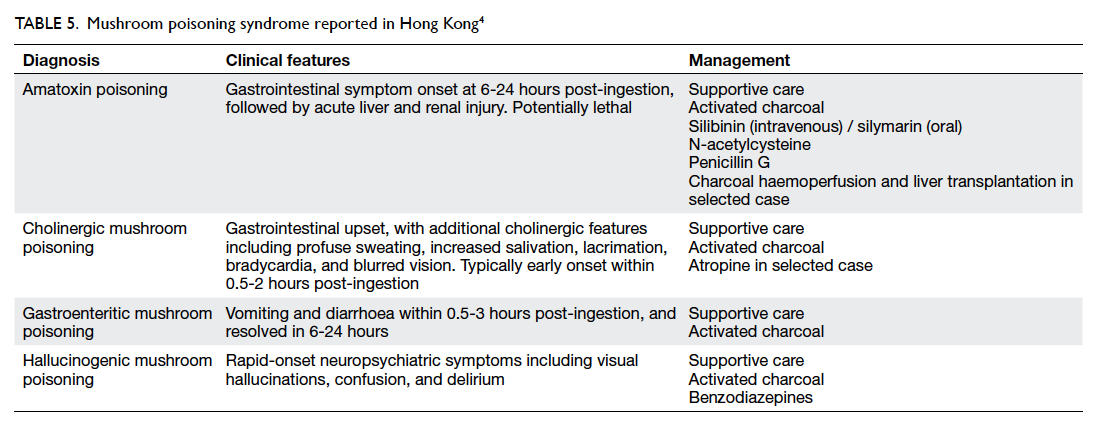

The typical clinical features and the management of

the four local mushroom poisoning syndromes are

summarised in Table 5.4

As an extensive urban city, commercially

sold cultivated mushrooms are easily available and

these are the mushrooms consumed by most Hong

Kong citizens every day. Nonetheless the Chinese

generally believes that wild-harvested products,

including mushrooms, have higher nutritional and

medicinal values. The risky behaviour of collecting

and consuming wild mushrooms was considered

to be rare in Hong Kong. This can be illustrated

by the relatively few reported cases of poisoning

during the study period. There are over 388 known

species of mushroom in Hong Kong,5 of which fewer

than 10% are edible, and a majority have unknown

edibility. Although mushrooms are macroscopic

organisms with visible morphological features, many

mushroom species share a similar appearance and

misidentification is common. There is no correlation

between a particular morphological feature and

poisonous nature of a mushroom species. Even

with genus Amanita, there are edible and inedible

species. There is no simple way to differentiate edible

and poisonous mushroom species. Even in expert

hands, mushroom identification frequently depends

on the microscopic features that can usually be seen

in a laboratory setting. Different edible and inedible

or poisonous mushroom species can share a similar

habitat and grow in close proximity in the wild.

Collection of mixed species often happens. Cooking

or other means of food processing cannot detoxify

a poisonous mushroom. With the report of life-threatening amatoxin poisoning from ingestion of local

wild mushrooms, Hong Kong citizens would be well

advised to stop the risky behaviour of consuming

self-picked mushrooms from the wild.

Consumption of poisonous mushrooms

can cause various signs and symptoms, such as

gastroenteritis, disturbances in central nervous

system, and liver failure.3 As mushroom identification

is usually not available early on in patient care,

doctors should treat their patients according to the

clinical syndrome (Table 54). An important predicting factor to consider is the latency from ingestion to

onset of symptoms. The finding of our case series

is compatible with overseas reports.3 6 Patients with

early-onset symptoms, typically within 6 hours

post-ingestion, all had a benign course of disease

(Table 2). The mainstay of treatment is supportive,

with intravenous fluids, antiemetic, antispasmodics,

or analgesic for those patients who present with

gastrointestinal symptoms.

Seven cases of amatoxin poisoning reported

in this case series confirms the existence of deadly

amatoxin-containing mushroom in our locality.

Poisonous Amanita species have long been found

in Hong Kong. Although local cases of amatoxin

poisoning have not been reported in Hong Kong

before 2013, it has been well-reported in mainland

China.7 8 9 According to a report published by

Guangzhou Municipal Centre for Disease Control

and Prevention, there were 92 cases of mushroom

poisoning with 13 deaths in the years 2002 to 2005.9

The reported species of mushroom involved in 70%

of cases were the amatoxin-containing mushroom

Amanita exitialis and the gastroenteritic mushroom

Chlorophyllum molybdites.9 For amatoxin poisoning,

the latency between ingestion and onset of

symptoms was typically 6 to 24 hours.3 For our seven

cases of amatoxin poisoning, this latency ranged

from 8 to 12 (median, 11) hours. There were four

male and three female patients, with a median age

of 44 (range, 29-74) years. All cases presented with

persistent vomiting and diarrhoea, deranged liver

function tests, and were able to give a history of wild

mushroom ingestion. Three were imported cases.

Two of them ate wild mushrooms in South Africa

and one patient ate wild mushrooms in China.

In four patients, wild mushrooms were picked

locally in the country park of the New Territories.

One imported case presented to hospital in Hong

Kong 5 days after wild mushroom consumption

and died of multi-organ failure soon after hospital

admission. The remaining six cases were managed

according to overseas experience in the treatment

of amatoxin poisoning.10 11 12 Treatment included

intravenous silibinin, oral silymarin, intravenous

N-acetylcysteine, oral multiple-dose activated

charcoal, high-dose intravenous penicillin, and early charcoal haemoperfusion. Two

local cases progressed to liver failure and required

liver transplantation. The remaining four cases

recovered with medical treatment. The diagnosis of

amatoxin poisoning was confirmed by the presence

of amatoxin and/or phallacidin in the urine in

five patients. Mycological examination identified

Amanita farinosa as the causative mushroom in a

local incident with two patients (Table 4). This is the

first report of this Amanita species in Hong Kong.

Hallucinogenic mushroom poisoning has

not been previously reported locally. The clinical

presentation of our four cases included dizziness,

headache, generalised weakness and numbness.

Three out of four patients presented with visual

hallucination. Although one patient did not report

any hallucinations, the patient was included as

a suspected case of hallucinogenic mushroom

poisoning based on compatible neurological

symptoms following consumption of porcini. The

symptom onset time was documented in two cases

and was 2 hours and 10 hours post-ingestion. The

source of mushroom was recorded in three cases as

mainland China. In only one case was mycological

identification performed (Table 4).

There were 13 cases of bolete poisoning in this

case series. All cases were related to consumption

of porcini. Porcini is considered to be a delicacy by

many mushroom lovers. It includes a number of

edible Boletus species, with Boletus edulis being the

best known. Not all Boletus are edible, however, and

mixing edible and inedible species is possible in wild

mushroom harvesting. There are reports of bolete

poisoning in English and Chinese literature.6 Bolete

consumption has been associated with outbreaks

of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Southwest China

(eg Yunnan province) in recent years.13 14 15 According

to these reports, consumption of inedible boletes

typically presented with gastrointestinal and

neurological symptoms including visual and auditory

hallucination. In our case series, two out of 13 cases

of bolete poisoning presented with neuropsychiatric

symptoms without gastrointestinal symptoms. The

two unrelated cases purchased mushrooms from

Yunnan province. The first patient presented with

numbness and weakness in all four limbs, dizziness,

and malaise after mushroom consumption. The

time of symptom onset was not documented and

symptoms resolved on the same day as mushroom

consumption. No mushroom sample was obtained

for identification. The second patient developed

dizziness, malaise, and visual hallucination 10 hours

after mushroom consumption. Her symptoms

resolved 48 hours post-ingestion. The causative

mushroom was identified as T nigerrimus, an inedible

bolete. Hallucinogenic mushroom poisoning caused

by T nigerrimus has not been reported in the English

literature.

In the cases of bolete poisoning, 11 out of 13

presented with gastrointestinal symptoms after

mushroom consumption. Four patients purchased

the mushrooms locally, and seven purchased the

mushrooms in China. In most cases, the mushrooms

were commercially packed as a product containing

wild-harvested boletes in dried slices. Mycological

identification was performed in 10 cases. These 10

cases represented six poisoning incidents. In five

incidents involving eight patients, the wild-harvested

porcini showed mixing up of edible porcini and

inedible boletes. In the remaining one incident, the

mushrooms were identified as an edible species,

although microscopic examination revealed them to

be rotten with dried worm and mold (Table 4). The diagnosis was food poisoning with possibly bacterial

contamination of spoiled mushroom in this incident.

Conclusion

Most cases of mushroom poisoning in Hong Kong

follow a benign course. Life-threatening cases of

amatoxin poisoning are occasionally seen. Doctors

should consider this diagnosis in patients who

present with gastrointestinal symptoms whose onset

is 6 hours or more after mushroom consumption.

In this review, all patients with amatoxin poisoning

picked the poisonous mushroom from the wild.

Wild mushroom picking and consumption should

be strongly discouraged.

References

1. Centre for Health Protection. Food poisoning associated

with wild mushroom. Communicable Disease Watch

2005;2:41-2.

2. Chan TY, Chiu SW. Wild mushroom poisonings in

Hong Kong. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health

2011;42:468-9.

3. Diaz JH. Syndromic diagnosis and management of

confirmed mushroom poisonings. Crit Care Med

2005;33:427-36. Crossref

4. Hoffman RS, Howland MA, Lewin NA, et al. Goldfrank’s

toxicologic emergencies. 10th edition. New York: McGraw-Hill Education; 2015.

5. Chang ST, Mao XL. Hong Kong mushrooms. Hong Kong:

The Chinese University Press; 1995.

6. Schenk-Jaeger KM, Rauber-Lüthy C, Bodmer M,

Kupferschmidt H, Kullak-Ublick GA, Ceschi A. Mushroom

poisoning: a study on circumstances of exposure and

patterns of toxicity. Eur J Intern Med 2012;23:e85-91. Crossref

7. Jin LM, Li Q. 金連梅, 李群. [Analysis of food poisoning incidents during 2004 to 2007 in China] 2004-2007年全國食物中毒事件分析

[in Chinese]. [Disease Surveillance] 疾病監測 2009;24:459-61.

8. Guo SH, Liu FQ, Liu XY, Chen Y. 郭綬衡,劉富强,劉秀英,陳焱. [Analysis of food-borne disease incidents

in Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Hunan, Hubei and Hebei Province

during 2000 to 2002] 2000-2002年江蘇、浙江、湖南、湖北、河北五省食物源性疾病發病情况分析 [in Chinese].

[Practical Preventive Medicine] 實用預防醫學 2004;11:867-71.

9. Mao XW, Li YY, He JY, Jing QL. 毛新武,李迎月,何潔儀,景飲隆. [Investigation of mushroom poisoning in Guangzhou City from 2000 to 2005] 廣州市 2000-2005年蘑菇中毒調查 [in Chinese]. [China Tropical Medicine] 中國熱帶醫學 2007;7:166-7.

10. Ward J, Kapadia K, Brush E, Salhanick SD. Amatoxin

poisoning: case reports and review of current therapies. J

Emerg Med 2013;44:116-21. Crossref

11. Enjalbert F, Rapior S, Nouguier-Soulé J, Guillon S,

Amouroux N, Cabot C. Treatment of amatoxin poisoning:

20-year retrospective analysis. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol

2002;40:715-57. Crossref

12. Giannini L, Vannacci A, Missanelli A, et al. Amatoxin

poisoning: a 15-year retrospective analysis and follow-up

evaluation of 105 patients. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2007;45:539-42. Crossref

13. Ji X, Ma Z, Zhu H, Pan YZ. 及曉,馬征,朱輝,潘軼竹.

[Report of two cases of mental disorder due to ingestion

of Boletus speciosus] 小美牛肝菌所致精神障礙2例 [in

Chinese]. [Clinical Journal of Psychiatry] 臨床精神醫學雜誌 2014;24:240.

14. Liu MW, Zhou H, Hao L, Zhang MQ. 劉明偉,周惠,郝麗,張明謙. [Analysis of 61 cases of boletus poisoning]

牛肝菌中毒61例分析 [in Chinese]. [Chinese Journal of

Misdiagnosis] 中國誤診學雜誌 2008;8:111.

15. Zhou YJ, Wei GL, Chen GH. 周亞娟,魏桂蘭,陳桂華.

[Investigation of Rhubarb boletus food poisoning] 一起黄粉牛肝菌食物中毒事件調查 [in Chinese]. [Occupational Health and Damage] 職業衛生與病傷2008;23:115-6.