© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

REMINISCENCE: ARTEFACTS FROM THE HONG KONG MUSEUM OF MEDICAL SCIENCES

The “golden lotuses”: bound feet

Condon Lee, Yan Tung

Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences

The practice of foot binding in Chinese women is

a cruel yet mysterious custom that continued for

over a thousand years. To civilised men at that time,

a pair of perfectly bound feet symbolised the ideal

of a woman’s beauty. The ‘golden lotuses’, as these

deformed feet were euphemistically called, were

regarded as pieces of art and objects of sexual desire.

The practice and history of foot binding have been

hotly discussed among historians.

The first written record of foot binding can

be traced to a book titled ‘Mo Zhuang Man Lu’

《墨莊漫錄》 by Zhang Bangji (張邦基), a scholar in the 12th century. According to Zhang, the practice

of foot binding began at the court of Li Yu (李煜),

the last emperor of the Southern Tang during the

Five Dynasties (907-960). He ordered his favourite

courtesan, Yao Niang (窅娘) to dance on a 6-foot-high

golden lotus, with her feet bound with white

silk cloth into the shape of a new moon. Other

dancers soon imitated the practice to attract the

attention of the emperor.1 The lotus foot became

the model of beauty among Chinese women. The

practice of foot binding started to flourish during

the Southern Song Dynasty (1127-1279) and was

encouraged by the renowned Confucian scholar Zhu

Xi (朱熹) who thought that it would restrain women

from unchaste and other immoral behaviour.2 By

the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), foot binding was

widespread throughout China and the practice came

to be regarded as a symbol of high social status. For

many women the practice gave them ‘hope’ for a

promising marriage. As an old Chinese saying goes:

‘if you love your daughter, bind her feet; if you love

your son, let him study’.3

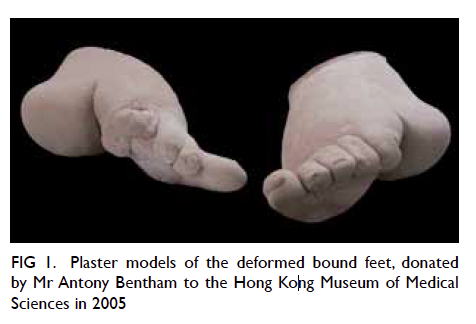

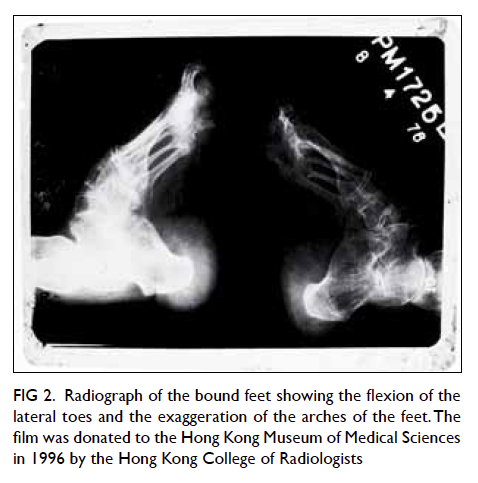

Foot binding had to start early at the age of 5 to

8 years before the arch of the foot had fully developed.

Its success depended on the skilful application of the

bandage—a process mostly carried out by the girl’s

mother or older sibling. One end of the bandage was

usually placed on the inside of the instep and carried

over the small toes, forcing them in towards the

sole. The big toe was left unbound. The bandage was

then wrapped around the heel forcefully to draw the

heel and toes close together. The aim was to make

the toes bend under and into the sole and to bring

the sole and heel as close together as was physically

possible (Figs 1 and 2).

Figure 1. Plaster models of the deformed bound feet, donated by Mr Antony Bentham to the Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences in 2005

Figure 2. Radiograph of the bound feet showing the flexion of the lateral toes and the exaggeration of the arches of the feet. The film was donated to the Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences in 1996 by the Hong Kong College of Radiologists

Foot binding drew the attention of foreigners

after China was forced to open to the imperial

powers in 1842. Dr John Preston Maxwell, a medical

missionary who went to Fujian from 1898 to 1919,

described two medical complications of foot

binding. The first was due to interference with blood

flow that caused skin ulcers, infection, and gangrene

associated with severe pain. If the foot was not

unbound, the toes or the whole foot could be lost. In

severe cases, women developed septicaemia to which

they might even succumb.4 The second complication

was displacement of the bones and weakening of the

ligaments of the ankle joints. Women with bound

feet had difficulty in walking because of the loss of

the normal architecture of the feet.

In 1997, a study of older women in Beijing

showed that the prevalence of bound feet was

surprisingly high—38% among women older than

80 years and 18% among those aged 70 to 79 years.

Compared with women with normal feet of the

same age, women with bound feet were significantly

more prone to fall and sustain hip fractures; less

able to squat or rise from a chair without assistance;

and less able to perform daily activities such as

preparing a meal, walking or climbing stairs. Their

limited weight-bearing activity led to reduced hip

bone density and increased risk of hip fracture from

falling,5 although a more recent study failed to show

such an increased risk, surmised by the authors as

possibly due to a compensatory improvement in

body balance.6

It was not until the late Qing Period in 1898

when Emperor Guangxu (reign 1875-1908), with

the support of Kang Youwei (康有為) and Liang

Qichao (梁啟超), led the Hundred Days’ Reform

that anti–foot binding became a national policy.

The ‘Foot Emancipation Society’ was formed to

encourage women to build ‘strong bodies and strong

action’. Kang and Liang’s efforts awakened liberal

consciousness among the Chinese. The movement

was discontinued after the Empress Dowager’s coup

but was reignited in 1902 when the Empress herself

issued an edict of anti–foot binding.7

When the Republic of China was established

in 1912, Dr Sun Yat-Sen promulgated an order to

prohibit foot binding on 13 March of the same year,

although it would be another 20 years before it

became a law of the Republic of China in 1932. The

practice of foot binding gradually disappeared in the

1950s.8

Acknowledgement

The authors are indebted to Prof Moira Chan-Yeung

for her invaluable advice.

References

1. Siku Quanshu 四庫全書. Available from: https://archive.org/details/06065053.cn. Accessed 18 Sep 2015.

2. Levy HS. Chinese footbinding: the history of a curious erotic custom. London: Neville Spearman; 1966: 44.

3. Ping W. Aching for beauty: footbinding in China. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press; 2000: 32.

4. Maxwell JP. On the evils of Chinese foot-binding. The China Medical Journal 1916;6:393-6.

5. Cummings SR, Ling X, Stone K. Consequences of foot binding among older women in Beijing, China. Am J Public

Health 1997;87:1677-9. Crossref

6. Qin L, Pan Y, Zhang M, et al. Lifelong bound feet in China: a quantitative ultrasound and lifestyle questionnaire

study in postmenopausal women. BMJ Open 2015;5:e006521. Crossref

7. Hong F. Footbinding, feminism and freedom: the liberation of women’s bodies in modern China. London: Frank

Cass; 1997: 66.

8. Gao JZ. Historical dictionary of modern China (1800-1949) (historical dictionaries of ancient civilizations and

historical eras). Maryland: Scarecrow Press Inc; 2009: 8.