DOI: 10.12809/hkmj144403

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Extrapulmonary involvement associated with Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection

T Liong, FHKCP, FHKAM (Medicine)1;

KL Lee, FHKCP, FHKAM (Medicine)1;

YS Poon, FHKCP, FHKAM (Medicine)1;

SY Lam, FHKCP, FHKAM (Medicine)1;

KM Kwok, MRCP1;

WF Ng, FHKAM (Pathology)2;

TL Lam, FHKAM (Pathology)2;

KI Law, FHKCP, FHKAM (Medicine)1

1 Intensive Care Unit, United Christian Hospital, Kwun Tong, Hong Kong

2 Department of Pathology, United Christian Hospital, Kwun Tong, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr KI Law (lawki@ha.org.hk)

Abstract

Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection usually presents

with upper and lower respiratory tract infection.

Extrapulmonary involvement is not uncommon,

however. We report two cases of predominantly

extrapulmonary manifestations of Mycoplasma

pneumoniae infection without significant

pulmonary involvement. Both cases were diagnosed

by serology. These cases illustrate the diversity of

clinical presentations of Mycoplasma pneumoniae

infection. Clinicians should maintain a high index

of suspicion.

Case reports

Case 1

A 20-year-old man who worked as a car mechanic

and enjoyed good health presented to United

Christian Hospital in Hong Kong in August 2013 after

collapsing suddenly at work. Ventricular arrhythmia

was detected by ambulance men and defibrillation

was performed 3 times with an automated external

defibrillator. He was then transferred to the

emergency department of the same hospital where

he was observed to have persistent ventricular

tachycardia and fibrillation. Advanced cardiac life

support was continued, repeated defibrillation was

performed and spontaneous circulation was restored

53 minutes later when he was then intubated.

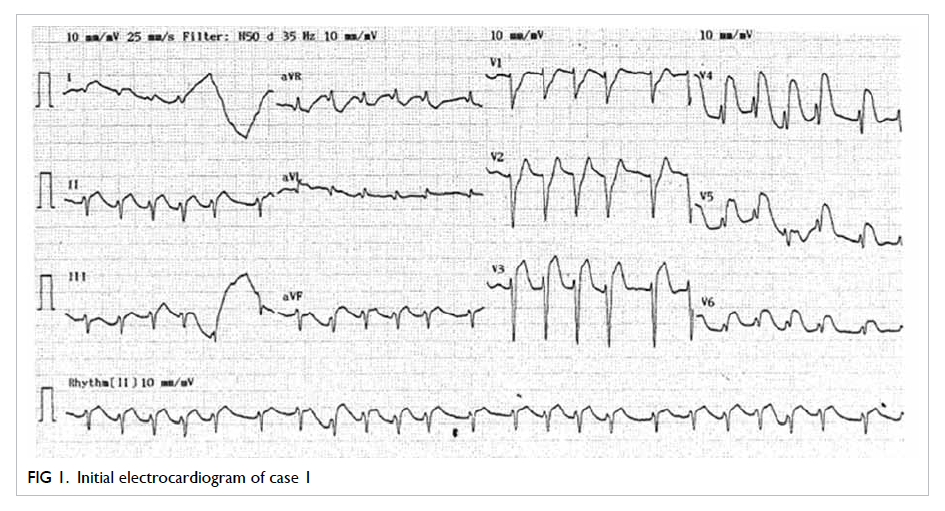

Initial electrocardiogram after successful

resuscitation showed diffuse ST elevation over

the chest leads (Fig 1). Echocardiogram revealed poor left ventricular systolic function with global

hypokinesia. Ad-hoc cardiac catheterisation was

carried out. There was no coronary lesion and the

patient was transferred to the intensive care unit

(ICU) for therapeutic hypothermia.

On arrival in ICU, the patient had a high fever

up to 39.7°C. Blood pressure was normal on low-dose

inotropes and pulse rate was 140 beats/minute.

Glasgow Coma Scale score was 2 for eye opening, 1

for verbal response, and 1 for motor response. His

pupils were equal and reactive, and bilateral plantar

reflexes were equivocal. Frothy sputum was evident

from the endotracheal tube but physical examination

was otherwise unremarkable.

Initial blood tests revealed elevated white

cell count (WCC) of 25.1 x 109 /L (reference range

[RR], 3.9-9.3 x 109 /L), neutrophilia of 21.6 x 109 /L

(RR, 1.8-6.2 x 109 /L), and normal lymphocyte count

of 2.9 x 109 /L (RR, 1.0-3.2 x 109 /L). Haemoglobin

level and platelet count were normal. He had mild

renal and liver impairment with urea 8.2 mmol/L

(RR, 2.8-8.1 mmol/L), and creatinine 138 µmol/L (RR,

62-106 µmol/L). Sodium and potassium levels were

normal and alanine transferase (ALT) was 152 IU/L

(reference level [RL], <41 IU/L). Creatinine kinase

was 6439 IU/L (RR, 39-308 IU/L), and troponin I

was 12 886 ng/L (RL, ≤14 ng/L). Initial urine toxic

screening was negative. His first chest X-ray (CXR)

showed right upper lobe consolidation, but repeated

CXR the next morning showed almost complete

resolution. Initial computed tomography (CT) of the

brain was unremarkable.

Amoxicillin/clavulanate was started to cover

aspiration pneumonia. Therapeutic hypothermia

for neuroprotection and continuous veno-venous

haemofiltration for acute kidney injury were

commenced. On day 4 the patient developed

convulsions and repeated CT brain showed diffuse

cerebral oedema. An electroencephalogram showed

diffuse encephalopathy compatible with severe

hypoxic-ischaemic insult. The patient remained in a

vegetative state and a tracheostomy was performed.

He had repeated episodes of ventilator-associated

pneumonia that were unresponsive to multiple

regimens of antibiotics and finally succumbed on

day 24 of admission.

Serology for viral studies was all negative.

Nonetheless, paired serology for Mycoplasma

pneumoniae on 26 August 2013 and 4 September

2013 showed a 4-fold decrease in antibody titres from

1:160 to 1:40, suggestive of recent M pneumoniae

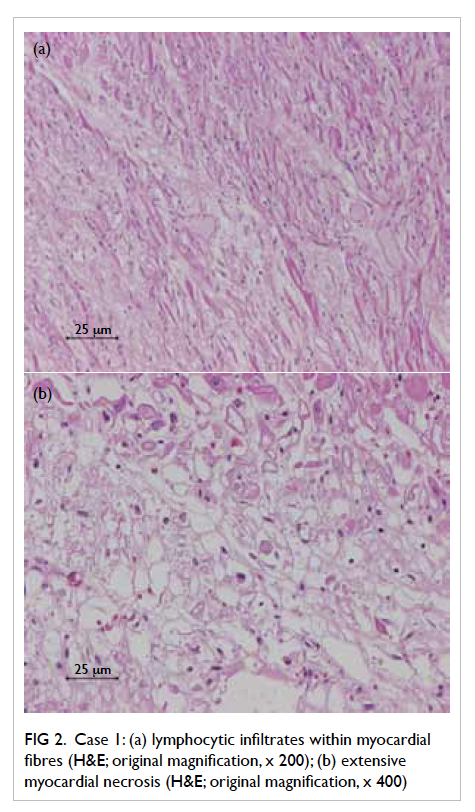

infection. Postmortem examination showed diffuse

lymphocytic infiltrates and extensive myocardial

necrosis within myocardial fibres (Fig 2). Reversetranscriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

for M pneumoniae on bilateral lung tissue and myocardium were negative.

Figure 2. Case 1: (a) lymphocytic infiltrates within myocardial fibres (H&E; original magnification, x 200); (b) extensive myocardial necrosis (H&E; original magnification, x 400)

Case 2

A 57-year-old security guard with a history of

infrequent asthma attacks but no regular follow-up

attended the emergency department of United

Christian Hospital in September 2013 with fever,

chills, and rigors. He also complained of a new-onset

maculopapular rash over the trunk and limbs that

developed 1 day prior to admission. He volunteered

that he was constantly exposed to insect bites due

to the close proximity of rural areas to his working

environment.

After admission to the medical ward, he

developed a high fever of 40.3°C. Blood pressure

was normal and pulse rate was 110 beats/minute.

Oxygen saturation could be maintained on low-flow

oxygen. Physical examination of the cardiovascular

system, chest, and abdomen was normal but a

maculopapular rash compatible with erythema

multiforme over the back, lower abdomen, and

bilateral lower limbs was observed. No eschar could

be seen.

Initial investigations revealed the following:

elevated WCC at 22.1 x 109 /L, neutrophilia of

21 x 109 /L, and lymphopenia of 0.2 x 109 /L. The

haemoglobin level was 117 g/L (RR, 135-173

g/L) and platelet count was 79 x 109 /L (RR,

160-420 x 109 /L). The clotting profile was mildly

deranged, with international normalised ratio of

1.3. He also had mild renal and liver impairment:

creatinine 111 µmol/L, ALT 74 IU/L, and aspartate

aminotransferase 101 IU/L. Initial CXR did not

reveal any consolidative changes.

Amoxicillin/clavulanate was commenced but

the patient’s condition deteriorated with development

of septic shock that required high-dose inotropes,

type I respiratory failure requiring high-flow oxygen,

acute kidney injury, and disseminated intravascular

coagulopathy despite change in antibiotic therapy to

piperacillin/tazobactam and azithromycin soon after

admission. He was transferred to ICU on day 3 of

admission and required intubation due to aspiration.

Antibiotics were changed to piperacillin/tazobactam

and doxycycline. His condition gradually improved

and he was successfully extubated and weaned off all

inotropes. The skin rash also resolved spontaneously

and repeated biochemistry tests revealed complete

resolution of renal and liver derangement.

Skin biopsy was not performed. The Widal test

and Weil-Felix tests were all negative. Paired serology

of M pneumoniae showed a 4-fold rise in antibody

titres from 1:<10 to 1:40, with confirmation of M

pneumoniae infection. Viral serology for rubella and

salmonella was not increased.

Discussion

We report two cases of M pneumoniae infection that

presented with extrapulmonary symptoms and no

significant respiratory involvement. Mycoplasma

pneumoniae usually infects the upper and lower

respiratory tract. Up to 50% of patients develop

only mild upper respiratory tract symptoms such as

cough, sore throat, malaise, and only 3% to 10% of

patients develop pneumonia.1

Approximately 25% of patients infected with M

pneumoniae develop extrapulmonary complications.

This can happen before, during, or after the onset

of or even in the absence of respiratory symptoms.1

An autoimmune reaction has been suggested as

the pathogenesis of many of these extrapulmonary

complications.1 The presence of organisms at an

extrapulmonary site, however, suggests that direct

invasion is also an important mechanism.2 3

The extrapulmonary manifestations associated

with M pneumoniae may be neurological, cardiac,

dermatological, musculoskeletal, haematological,

and gastro-intestinal.4 Of these, neurological and

dermatological symptoms are recognised as among

the most common extrapulmonary manifestations

of M pneumoniae infection.1 4

A wide range of dermatological manifestations

has been described in patients with M pneumoniae

infection. Mild symptoms include a maculopapular

or vesicular rash.5 Erythema multiforme and Stevens-Johnson syndrome have a strong association with M pneumoniae infection.4 6 7 8

The patient in case 2 presented with sepsis and

erythema multiforme. He was not prescribed any

medication associated with erythema multiforme.

Since a list of infective causes of erythema

multiforme had been excluded by serology tests,

his skin manifestation was most likely due to M

pneumoniae infection.

Cardiac involvement is regarded as an

uncommon complication of M pneumoniae infection.1 Pericarditis, myocarditis or pericardial effusion with or without tamponade effect have been

described.1 It is more commonly found in adults than

in paediatric patients.9 Fortunately, the outcome is

generally good. Only a minority of patients had long-term sequelae and mortality is rare.10

Myocarditis associated with M pneumoniae

infection that presents with ventricular arrhythmia

as in case 1 is rare. We excluded other common

causes of ventricular arrhythmia by initial blood

tests, toxic screening, cardiac catheterisation, and

CT brain. A 4-fold decrease in antibody titre of paired

sera confirmed recent M pneumoniae infection.

Autopsy results showed lymphocytic myocarditis.

It is plausible, although not confirmative, that M

pneumonia–associated myocarditis due to direct

invasion of M pneumoniae cannot be shown by

RT-PCR. Other differential diagnoses of lymphocytic

myocarditis such as viral myocarditis were excluded

by viral serology.

In addition to the diverse clinical

manifestations, clinicians should also be aware of

widespread macrolide resistance of M pneumoniae

in Asia, including Hong Kong.11 High rates of

macrolide resistance of up to 70% to 80% have been

reported in China and Japan.12 13 14 Prompt adjustment

of antibiotics to cover atypical pathogens is essential

to successful treatment, as in our second patient.

Consideration of alternatives such as doxycycline or

fluoroquinolones as empirical treatment of atypical

pathogens in areas with high rates of resistance may

be appropriate.14

In conclusion, although M pneumoniae most

commonly presents with respiratory tract symptoms,

extrapulmonary manifestations are not uncommon.

Clinicians should be aware of variable clinical

presentations of M pneumoniae and macrolide

resistance in our locality.

References

1. Waites KB, Talkington DF. Mycoplasma pneumoniae

and its role as a human pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev

2004;17:697-728. Crossref

2. Kasahara I, Otsubo Y, Yanase T, Oshima H, Ichimaru

H, Nakamura M. Isolation and characterization of

Mycoplasma pneumoniae from cerebrospinal fluid of a

patient with pneumonia and meningoencephalitis. J Infect

Dis 1985;152:823-5. Crossref

3. Saïd MH, Layani MP, Colon S, Faraj G, Glastre C, Cochat

P. Mycoplasma pneumoniae–associated nephritis in

children. Pediatr Nephrol 1999;13:39-44. Crossref

4. Sánchez-Vargas FM, Gómez-Duarte OG. Mycoplasma

pneumoniae—an emerging extra-pulmonary pathogen.

Clin Microbiol Infect 2008;14:105-17. Crossref

5. Baum SG. Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in

adults. Available from: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/mycoplasma-pneumoniae-infection-in-adults?

source=search_result&search=Mycoplasma+pneumoniae+infection+in+adults.&selectedTitle=1%7E116.

Accessed Aug 2015.

6. Vanfleteren I, Van Gysel D, De Brandt C. Stevens-Johnson

syndrome: a diagnostic challenge in the absence of skin

lesions. Pediatr Dermatol 2003;20:52-6. Crossref

7. Vargas-Hitos JA, Manzano-Gamero MV, Jiménez-Alonso

J. Erythema multiforme associated with Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Infection 2014;42:797-8. Crossref

8. Rock N, Belli D, Bajwa N. Erythema bullous multiforme:

a complication of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. J Pediatr 2014;164:421. Crossref

9. Formosa GM, Bailey M, Barbara C, Muscat C, Grech

V. Mycoplasma pneumonia—an unusual cause of acute

myocarditis in childhood. Images Paediatr Cardiol

2006;8:7-10.

10. Paz A, Potasman I. Mycoplasma-associated carditis. Case

reports and review. Cardiology 2002;97:83-8. Crossref

11. Ho PL, Wong SY, editors. Reducing bacterial resistance with

IMPACT—Interhospital Multi-disciplinary Programme on Antimicrobial ChemoTherapy. 4th ed. Hong Kong SAR: Centre for Health Protection; 2012.

12. Yin YD, Cao B, Wang H, et al. Survey of macrolide

resistance in Mycoplasma pneumoniae in adult patients with community-acquired pneumonia in Beijing, China [in Chinese]. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi 2013;36:954-8.

13. Eshaghi A, Memari N, Tang P, et al. Macrolide-resistant

Mycoplasma pneumoniae in humans, Ontario, Canada,

2010-2011. Emerg Infect Dis 2013;19(9). doi: 10.3201/eid1909.121466. Crossref

14. Okada T, Morozumi M, Tajima T, et al. Rapid effectiveness

of minocycline or doxycycline against macrolide-resistant

Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in a 2011 outbreak

among Japanese children. Clin Infect Dis 2012;55:1642-9. Crossref