DOI: 10.12809/hkmj144357

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Churg-Strauss syndrome from an orthopaedic perspective

KL Kung, MB, BS;

PK Yee, MB, ChB, FHKCOS

Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Chai Wan, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr KL Kung (lepetitcarmen@gmail.com)

Abstract

Churg-Strauss syndrome, which has been frequently

described by physicians in the literature, is a

small and medium-sized vessel systemic vasculitis

typically associated with asthma, lung infiltrates,

and hypereosinophilia. We report a case of Churg-Strauss syndrome with presenting symptoms of

bilateral lower limb weakness and numbness only.

The patient was admitted to an orthopaedic ward

for management and a final diagnosis was reached

following sural nerve biopsy. The patient’s symptoms

responded promptly to steroid treatment and she

was able to walk with a stick 3 weeks following

admission. This report emphasises the need to be

aware of this syndrome when managing patients

with neurological deficit in order to achieve prompt

diagnosis and treatment.

Introduction

Churg-Strauss syndrome (CSS) is a small and

medium-sized vessel vasculitis that can affect

different organs. The usual presentation is sub-optimised

control of asthma together with

involvement of other organs such as the heart,

skin, and nervous system. It seldom presents with

isolated neurological symptoms and has thus far

not been reported from an orthopaedic aspect. We

report a case of CSS in a patient who presented with

neurological symptoms and who was admitted to the

orthopaedic ward via casualty because of lower limb

weakness and numbness.

Case report

A 66-year-old Chinese woman was admitted to the

orthopaedic ward for 2 weeks in May 2013 because

of weakness and numbness in both lower limbs.

She had a more than 10 years’ history of asthma

that was controlled with an inhaled bronchodilator

and oral theophylline and terbutaline. The patient

was prescribed an oral steroid intermittently for

acute control. From January 2012 until the current

admission, she had also been taking a leukotriene

receptor antagonist (montelukast).

On admission, the patient complained of severe

dysesthesia over both lower limbs, mainly below

knee level. There was mild left proximal thigh pain.

She had no low back pain and denied a history of

recent trauma. The symptoms rendered the patient

unable to walk.

Upon physical examination, she was

afebrile, and cardiopulmonary and dermatological

examination was unremarkable. Neurological

examination revealed decreased sensation over both

lower limbs in a glove and stocking distribution.

Power of the muscles supplied by the peroneal

and tibial nerves was grade 4 according to Medical

Research Council grading system. Reflexes were

diminished over both lower limbs. Per rectal

examination revealed normal anal tone.

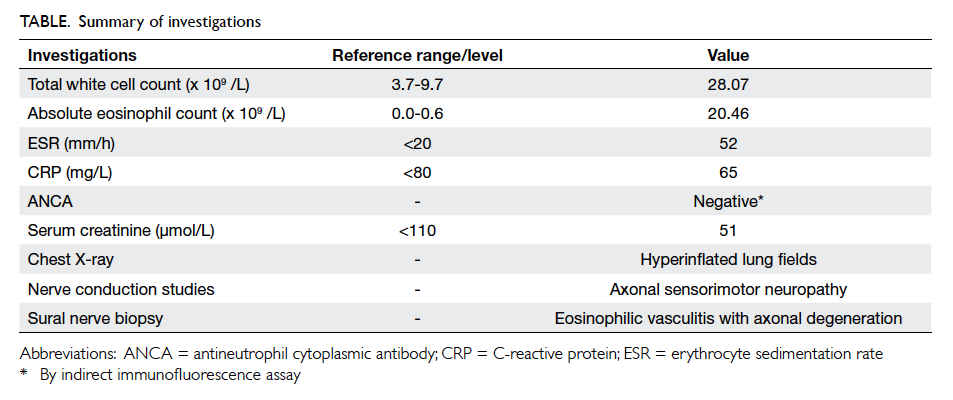

Blood tests revealed elevated white cell count

to 28.07 x 109 /L with a predominance of eosinophils

(20.46 x 109 /L). C-reactive protein was 65 mg/L.

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 52 mm/h.

Serum calcium, phosphate, alkaline phosphatase

and creatine kinase level were normal. Sepsis

workup including blood culture and urine culture

were negative (Table).

Radiography of the lumbar spine revealed

grade-one spondylolisthesis at the lumbar 4 and 5

level. Radiography of the pelvis was unremarkable.

Chest radiography showed slightly hyperinflated

lung. Subsequent magnetic resonance imaging

with contrast of the lumbar spine and pelvis was

performed in view of the radiographic findings of

the lumbar spine and the neurological deficit in the

lower limbs. There was neither evidence of nerve

root and cord compression nor infection around the

lumbar spine.

Nerve conduction study showed absence of

the compound muscle action potential (CMAP) of

the right peroneal nerve recorded at the extensor

digitorum brevis muscle. The CMAP was also

decreased over bilateral tibialis anterior muscles.

These results were suggestive of an axonal type of

motor neuropathy over bilateral peroneal nerves and

a sensory type of axonal neuropathy over the right

lower limb. There was no involvement of the upper

limbs.

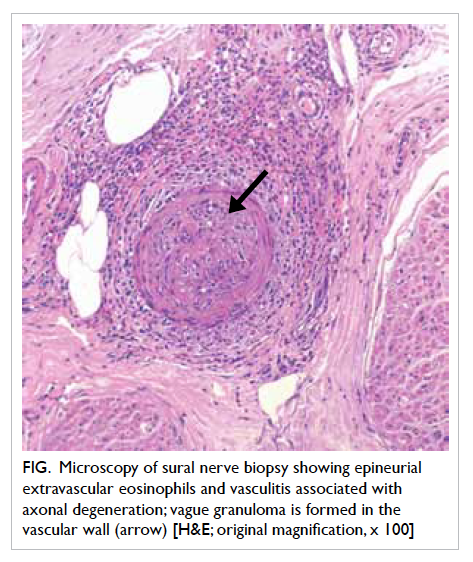

Left sural nerve biopsy revealed epineurial

extravascular eosinophils and vasculitis associated

with axonal degeneration (Fig). There was one small epineurial artery infiltrated by eosinophils,

polymorphs, and lymphocytes. Vague granuloma

were present in the vascular wall. These features

were consistent with CSS based on the American

College of Rheumatology Classification criteria.1

The Table summarises the investigations.

Figure. Microscopy of sural nerve biopsy showing epineurial extravascular eosinophils and vasculitis associated with axonal degeneration; vague granuloma is formed in the vascular wall (arrow) [H&E; original magnification, x 100]

A rheumatologist was consulted who

diagnosed CSS with peripheral neuropathy.

Montelukast was discontinued in view of the

possible association of the CSS. Oral prednisolone

40 mg daily was prescribed to the patient and an oral

bisphosphonate was given to prevent osteoporosis.

Distal lower limb power improved to grade 5 shortly

following steroid treatment and there was marked

improvement in pain and numbness. The eosinophil

count and elevated inflammatory markers reduced

rapidly over 6 days. The patient was discharged from

the orthopaedic ward 2 weeks after treatment and

was able to walk with a stick. The patient has been

referred to a day hospital for further rehabilitation.

Discussion

Churg-Strauss syndrome is an entity frequently

described by rheumatologists in the literature.2 It has

seldom been reported by an orthopaedic surgeon.

This case illustrates that common symptoms such as

pain and numbness, frequently encountered when

treating orthopaedic patients, may not be necessarily

due to an orthopaedic problem. It may be a medical

disease that requires prompt and specific treatment.

Allergic granulomatosis angiitis, or CSS, is

a type of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody–associated small-vessel systemic vasculitis. Other

diseases under the same group include microscopic

polyangiitis and granulomatosis with polyangiitis,

formerly known as Wegener’s granulomatosis.3 It

was first described in 1951 by Dr Jacob Churg and

Dr Lotte Strauss at Mount Sinai Hospital and is

characterised by eosinophilic vasculitis that affects

the small and medium-sized vessels. It describes

the clinical symptoms of the pathological entity

allergic angiitis and granulomatosis. The American

College of Rheumatology has recommended that

diagnosis of the syndrome is considered when four

of the following features are present: (1) asthma, (2)

eosinophils constituting more than 10% of the white

cell count, (3) neuropathy, (4) non-fixed pulmonary

infiltrates on radiography, (5) extravascular

granulomas, and (6) abnormalities of the paranasal

sinuses.1 The presence of four or more criteria yields

a diagnostic sensitivity of 85% and a specificity of

99%.1

Despite variable clinical manifestations,

pathological findings will include necrotising

eosinophilic vasculitis that may result from

endothelial cell adhesion and leukocyte activation,

with subsequent necrotising vasculitis in several

organ systems.

The pathogenesis of the syndrome is unclear,

but it has been shown that HLA-DRB3 is a genetic

risk factor for development. There have been reports

about the strong association between CSS and the

use of a leukotriene receptor antagonist (LTRA)

such as montelukast. The mechanism by which

LTRAs might cause eosinophilic vasculitis remains

unclear, however. It is known that LTRAs do not

inhibit leukotriene B4 (LTB4), which is a powerful

chemoattractant for eosinophils. This could lead

to increased plasma levels of LTB4 and trigger

eosinophilic inflammation. Nevertheless, LTRA

has a somewhat causative role in the development

of CSS. A controlled study with a large number of

patients is required to verify this conclusion.

The clinical presentation is variable. Some

people have only mild symptoms, while others

experience severe or life-threatening complications.

There are three stages of CSS, but not every patient

will develop all three phases or in the same order.

They include:

(1) Allergic stage: the first stage of the syndrome in which the patient develops a number of allergic reactions including asthma, hay fever, and sinusitis.

(2) Eosinophilic stage: hypereosinophilia is found in the blood or tissue causing serious local damage. The lungs and digestive tract are most often involved. The symptoms may be relapsing and remitting and last for months or years.

(3) Vasculitic stage: the hallmark of this stage is blood vessel inflammation. The blood vessels are narrowed by inflammation and blood flow to tissue is jeopardised. During this phase, a feeling of general ill-health along with unintended weight loss, lymphadenopathy, weakness, and fatigue may occur.

(1) Allergic stage: the first stage of the syndrome in which the patient develops a number of allergic reactions including asthma, hay fever, and sinusitis.

(2) Eosinophilic stage: hypereosinophilia is found in the blood or tissue causing serious local damage. The lungs and digestive tract are most often involved. The symptoms may be relapsing and remitting and last for months or years.

(3) Vasculitic stage: the hallmark of this stage is blood vessel inflammation. The blood vessels are narrowed by inflammation and blood flow to tissue is jeopardised. During this phase, a feeling of general ill-health along with unintended weight loss, lymphadenopathy, weakness, and fatigue may occur.

Asthma is the central feature of CSS and

precedes the systemic manifestations in almost

all cases. Upper airway findings can include

sinusitis, allergic rhinitis, and nasal polyps. Cardiac

involvement represents the major cause of mortality.

Granulomatous infiltration of the myocardium and

coronary vessel vasculitis are the most common

lesions. Congestive heart failure may develop

rapidly and is often responsible for the mortality.

Gastro-intestinal involvement such as abdominal

pain, diarrhoea, and bleeding may also occur.

Bowel perforation is the most severe manifestation

and is one of the major causes of death. The

glomerular lesion that typifies CSS is focal segmental

glomerulonephritis with necrotising crescents. Its

involvement is one of the poor prognostic factors.

Arthralgias are frequent but arthritis with local

inflammatory findings is rare, and joint deformity

and radiographic erosions are usually not seen.

Large articular joints are affected more than small

joints. The symptoms usually regress quickly with

treatment. Skin involvement occurs in 50% to 68%

of patients and reflects the predilection for small

vessels. Lesions are red or violaceous, and occur

primarily on the scalp and the limbs or hands and

feet. They are often bilateral and symmetrical.4

Peripheral neuropathy, as in our case, is

common in patients with CSS (65-75%).5 6 The

initial symptoms of neuropathy usually include

an acute onset of tingling or painful paresthesia in

the extremities. These symptoms predominantly

occur in the distal portions of the extremities,

particularly the lower limbs. In the initial phase, the

distribution of sensory impairment usually takes

the form of a mononeuritis multiplex pattern. As

the disease progresses, it eventually evolves into

a polyneuropathic pattern. Muscle weakness, to a

variable extent and degree of asymmetry, may also

be evident. There will be decreased or absent deep

tendon reflexes corresponding to the distribution of

nerves involved. Electromyography reveals axonal

nerve involvement and often detects more extensive

involvement than the clinical symptoms would

indicate. With treatment, mononeuritis multiplex

regresses progressively and patients may recover

without sequelae. Prompt diagnosis and treatment

are of paramount importance in managing CSS with

neuropathy. If medical treatment is delayed, atrophy

and weakness of the limbs may be irreversible

and will require additional rehabilitation therapy

including strengthening exercises, balance training,

and ambulation training.

In the treatment of CSS, as with other forms of

vasculitis, the symptoms respond to corticosteroids

or other immunosuppressive drugs, eg

cyclophosphamide and methotrexate.7 If refractory

to these agents, intravenous immunoglobulin is

the treatment of choice. Leukocytosis, eosinophilia,

and raised erythrocyte sedimentation rates usually

respond promptly after administration of these

agents. Neuropathic pain also decreases rapidly

in 85% of patients. There is speculation that the

initial clinical course and the degree of systemic

inflammatory involvement may influence long-term

functional prognosis. Recent trials of treatment

include immunomodulators such as rituximab,

an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, and tumour

necrosis factor–alpha.8

In this article, we have reviewed the clinical

features, diagnostic criteria, and treatment options

of CSS. In middle-aged or elderly patients, lower

limb numbness and pain are frequently attributed

to the degenerative spine with stenosis or nerve root

compression. It is tempting to conclude that a patient

has spinal stenosis or lumbar spondylosis in the

presence of degenerative lumbar spine radiographs.

This case highlights the need for clinicians to be

vigilant for these manifestations in addition to the

various diagnoses of spinal pathology when a patient

presents with limb numbness and weakness together

with a history of asthma and raised eosinophil count.

Because signs and symptoms are both numerous and

at times unassuming, it is notoriously difficult to

diagnose CSS at the very initial phase. Nonetheless,

significant neuropathic involvement may be

prevented if a patient receives adequate therapy to

induce remission of disease and prevent relapse.

With treatment, most of the symptoms in any of

the three phases can be relieved. We would like to

raise the awareness of such an entity in treating

patients with neuropathy. Close collaboration with

rheumatologists in treating such a complex illness,

including prompt diagnosis by performing nerve

biopsy by an orthopaedic surgeon and prompt

medical treatment by a rheumatologist, is the key to

successful management.

References

1. Masi AT, Hunder GG, Lie TT, et al. The American College

of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of

Churg-Strauss syndrome (allergic granulomatosis and

angiitis). Arthritis Rheum 1990;33:1094-100. Crossref

2. Churg J, Strauss L. Allergic granulomatosis, allergic rhinitis,

and periarthritis nodosa. Am J Pathol 1951;27:277-301.

3. Falk RJ, Gross WL, Guillvein L, et al. Granulomatosis

with polyangiitis (Wegener’s): An alternative name for

Wegener’s granulomatosis. Arthritis Rheum 2011;63:863-4. Crossref

4. Guillevin L, Pagnoux C, Mouthon L. Churg-Strauss

syndrome. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2004;25:535-45. Crossref

5. Sehgal M, Swanson JW, DeRemee RA, Colby TV.

Neurologic manifestations of Churg-Strauss syndrome.

Mayo Clin Proc 1995;70:337-41. Crossref

6. Hattori N, Ichimura M, Nagamatsu M, et al.

Clinicopathological features of Churg-Strauss syndrome–associated neuropathy. Brain 1999;122:427-39. Crossref

7. Bosch X, Guilabert A, Espinosa G, Mirapeix E. Treatment

of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody associated

vasculitis: a systematic review. JAMA 2007;298:655-69. Crossref

8. Thiel J, Hässler F, Salzer U, Voll RE, Venhoff N. Rituximab

in the treatment of refractory or relapsing eosinophilic

granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss

syndrome). Arthritis Res Ther 2013;15:R133. Crossref