© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

REMINISCENCE: ARTEFACTS FROM THE HONG KONG MUSEUM OF MEDICAL SCIENCES

Destructive obstetric instruments: what do they destroy?

KH Lee, MD, FRCOG

Director, Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences Society

They destroy the fetus in the uterus.

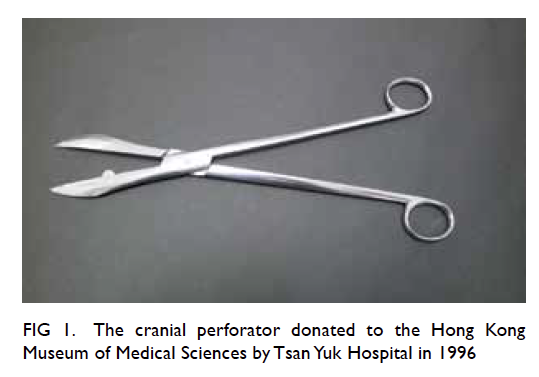

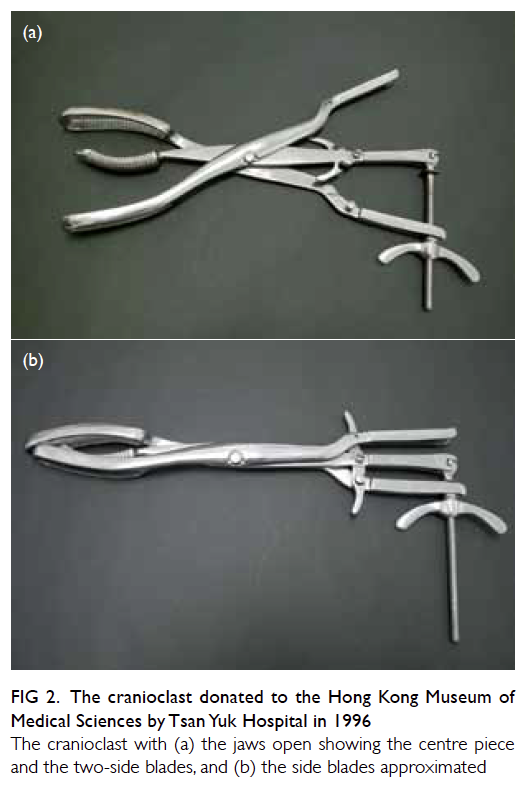

The instruments shown in the figures were

used more than a hundred years ago to perforate

and crush the fetal head in cases of hydrocephalus

or disproportion, and in prolonged labour when the

fetus had died. The perforator was used to puncture

the fetal skull, release the contents, and reduce its

size (Fig 1). The centre piece of the cranioclast was

used to make the perforation (Fig 2a) and then the

two-side blades approximated by tightening the

screw on the handle to crush the fetal skull (Fig 2b).

Figure 1. The cranial perforator donated to the Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences by Tsan Yuk Hospital in 1996

Figure 2. The cranioclast donated to the Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences by Tsan Yuk Hospital in 1996

The cranioclast with (a) the jaws open showing the centre piece and the two-side blades, and (b) the side blades approximated

The art of midwifery must be one of the oldest

of acquired skills. In its early days, difficult deliveries

and obstructed labours must have taxed the skills

of the obstetrician. When the fetus was stuck at the

pelvis it would die from the prolonged labour and

asphyxia. Assisted delivery by means of forceps and

caesarean section were not introduced until the 17th

century. Various destructive instruments seem to

have been known for a very long time, but there are

scanty descriptions of them in texts.

Francois Mauriceau (1637-1709), the famous

French obstetrician, was the first to describe

craniotomy and extraction of a dead child. He

invented a perforator and another instrument to

extract a dead baby after making a hole in the head

so that the brain could come out and the bones

collapse. In the 18th century, William Osborn (1736-1808) was a great believer in craniotomy. He claimed

to have once successfully extracted a fetus through

a pelvis with an anteroposterior space as narrow as

three quarters of an inch.1 2

When I was a student in obstetrics at the

new Tsan Yuk Hospital in 1957, I first saw the

instruments shown here. They were placed in the

library of the hospital, moved there from the old

Tsan Yuk Hospital. I never saw them used. They

were donated to the Hong Kong Museum of Medical

Sciences by the Hospital in 1996 at the foundation

of the Museum. The reason why these destructive

instruments became obsolete is obvious: they

were dangerous instruments. Often they not only

destroyed the fetus, but also caused serious injury to

the mother. Since the 20th century, delivery has been

made safe with the use of forceps, vacuum extraction,

and caesarean section. Destructive operations have

been abandoned forever.

Nevertheless we have great sympathy for our

ancestors. In such difficult situations, no intervention

might also be disastrous. The following sad story gives

an account of the plight of those who belonged to the

non-intervention school. Sir Richard Croft (1762-1818) was the obstetrician attending the only daughter

of King George IV, Princess Charlotte, whose son

would have been in line to the throne. The princess

had a very difficult delivery, but Croft allowed her

to go for 2 whole days of labour without assistance,

even denying her any sustenance, although forceps

were at hand. When the child was delivered, stillborn,

it was found to be a large, 9-pound male. The poor

exhausted mother had a retained placenta that had

to be delivered manually, by which time she was very

weak indeed. Croft’s brother-in-law, Baillie, advised

restoratives, and she was given large quantities of port

wine. She died the following morning. Sir Richard

was so criticised for his handling of the case that he

committed suicide by shooting himself.2

References

1. O’Dowd MJ, Philipp EE. The history of obstetrics and gynaecology. New York and London: Parthenon Publishing Group; 1994: 141.

2. Radcliffe W. Milestones in midwifery. Bristol: John Wright & Sons Ltd; 1967: 50.