Hong Kong Med J 2015 Oct;21(5):455–61 | Epub 28 Aug 2015

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj154572

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

REVIEW ARTICLE

Using the script concordance test to assess clinical reasoning skills in undergraduate and postgraduate medicine

SH Wan, MB, ChB, MRCP (Edin)

School of Medicine Sydney, University of Notre Dame, 160 Oxford Street, Darlinghurst, NSW 2010, Australia

Corresponding author: Dr SH Wan (michael.wan@nd.edu.au)

Abstract

The script concordance test is a relatively new format

of written assessment that is used to assess higher-order

clinical reasoning and data interpretation skills

in medicine. Candidates are presented with a clinical

scenario, followed by the reveal of a new piece of

information. The candidates are then asked to assess

whether this additional information increases or

decreases the probability or likelihood of a particular

diagnostic, investigative, or management decision.

To score these questions, the candidate’s decision in

each question is compared with that of a reference

panel of expert clinicians. This review focuses on

the development of quality script concordance

questions, using expert panellists to score the items

and set the passing score standard, and the challenges

in the practical implementation (including pitfalls to

avoid) of the written assessment.

Introduction

Script concordance test (SCT) is a relatively new

format of written assessment to assess higher-order

clinical reasoning and data interpretation skills of

medical candidates.1

In recent years, universities and postgraduate

colleges worldwide have used SCT for both formative

and summative assessment of clinical reasoning in

various medical disciplines including paediatric

medicine, paediatric emergency medicine, neurology,

orthopaedics, surgery, and radiology.2 3 4 5 6 7 8 In the classic

written assessment, multiple-choice questions

(MCQ) and short-answer questions (SAQ) usually

examine the candidates’ simple knowledge recall at

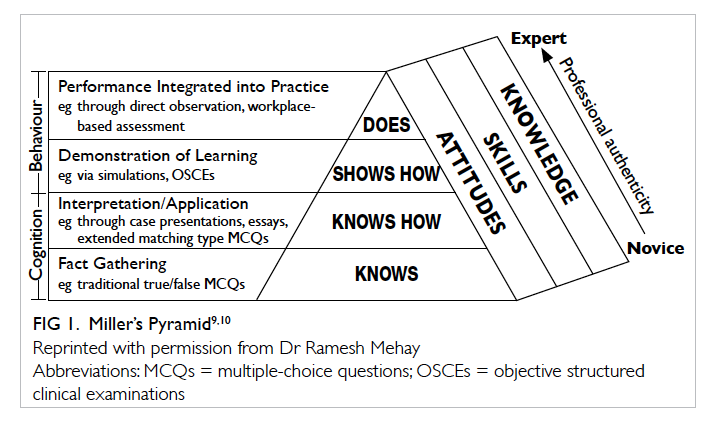

the lowest ‘knows’ level of the Miller’s Pyramid (Fig 1).9 10 Questions in SCT are able to test candidates at the higher order of thinking at the ‘knows how’ and even ‘shows how’ level. It is a unique assessment

tool that targets the essential clinical reasoning and

data interpretation skills in a very authentic way that

reflects the element of ‘uncertainty’ in real-world

clinical scenarios prevalent in clinical practice.

This is the key aspect of clinical competency that

enables medical graduates or fellows in training to

link and transfer their mastery of declarative clinical

knowledge and skills into clinical practice in a real

clinical setting. Recent literature reports the value

of using SCT to assess other areas of disciplines

where classic questions are difficult to develop, for

example, in assessing medical ethical principles and

professionalism.11

The structure and format of script concordance test

In SCT, candidates are presented with a clinical

vignette/scenario, followed by the reveal of a new

piece of information. The candidates are then

asked to assess whether this additional information

increases or decreases the probability or likelihood

of the suggested provisional diagnosis, and increases

or decreases the usefulness/appropriateness of a

proposed investigation or management option.

The process reflects everyday real-world decision-making

processes where clinicians retrieve their

‘illness scripts’ or network of knowledge (about

similar patient problems and presentations stored

in their memory) when faced with uncertainty in a

clinical presentation. This enables them to determine

the follow-on diagnosis and management options

most appropriate to the situation. As further clinical

encounters are experienced, the scripts are updated

and refined.12 Script concordance test assesses the

candidates’ clinical reasoning and data interpretation

ability in the context of uncertainty, particularly

involving ill-defined patient problems in clinical

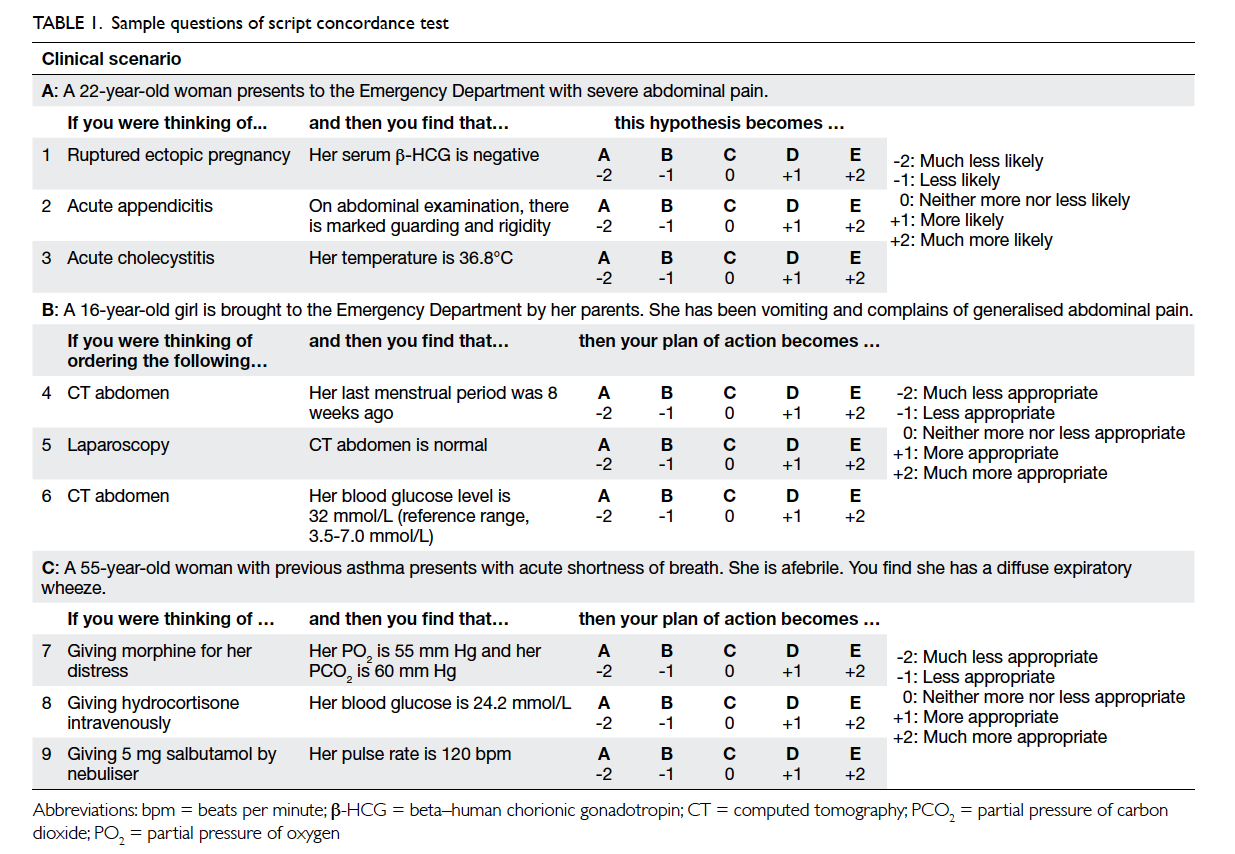

practice.13 Sample SCT questions in Table 1 illustrate

the structure and format of the SCT questions. As

the clinical scenario unfolds, additional data such as

clinical photos, radiological images, or audiovisual

material can also be presented to enhance the

authenticity of the scenarios.5 14 15

In scenario A in Table 1, the ‘clinical vignette’

is that of a 22-year-old woman who presents to the

Emergency Department with severe abdominal

pain. A piece of ‘new information’ is then revealed

that her serum beta–human chorionic gonadotropin

(β-HCG) is normal. The candidate is asked whether

this additional information makes the ‘diagnosis’ of

ectopic pregnancy: much less likely (-2), less likely

(-1), neither more nor less likely (0: no effect on the

likelihood), more likely (+1), or much more likely

(+2). The next piece of new information (independent

of the first one) is that the examination shows

marked guarding and rigidity of the abdomen and

the candidate is asked to determine the likelihood of

a diagnosis of acute appendicitis.

In scenario B in Table 1, a similar format is

used to assess the appropriateness of ordering an

investigation in relation to the respective piece

of additional information. The first question asks

for the appropriateness of ordering a computed

tomographic scan of the abdomen for a 16-year-old

girl who presents with acute abdominal pain if her

last menstrual period was 8 weeks ago.

In scenario C in Table 1, the focus is on

the usefulness of different management options

after being presented with different pieces of new

information related to the clinical vignette.

In preparing candidates to answer the

questions, it is crucial to emphasise that each piece

of new information is independent of the previous

piece but in the same clinical setting. For example,

in scenario A, when answering the second question

given that she has guarding and rigidity in the

abdomen, she does NOT have a serum β-HCG test

done.

With respect to the likelihood descriptors

used in the SCT questions for the diagnosis type

of scenario, the preference is to use the option of

“much less likely (-2)” rather than “ruling out the

diagnosis”; and “much more likely (+2)” rather than

“almost certain/definite diagnosis”. This will allow

candidates to use the full range of the five options.

In the practice of medicine, there are usually few

situations wherein a diagnosis can be confidently

excluded or definitely diagnosed with a few pieces of

information provided.3

There are nonetheless limitations to the

design and format of SCT. Candidates cannot seek

additional information to that given in the question;

the scenario is only a snapshot of the clinical

encounter without the comprehensive history,

physical examination, and investigations that would

be particularly desirable in an ambiguous clinical

situation.16

Scoring script concordance test

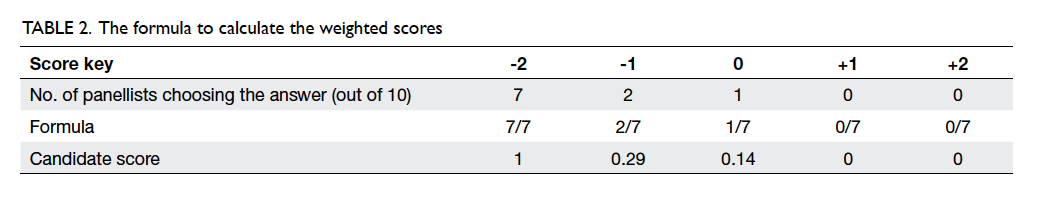

To score these questions, the candidate’s decision in

each question is compared with that of a reference

panel of expert clinicians. Each member of the

panel attempts the same set of questions and the

answers are recorded. As there is no single best

correct answer to the question, a full (1) mark will be

awarded if the candidate’s decision concurs (hence

the name ‘concordance’) with the majority of the

expert panel. A proportional (partially credited or

weighted) score (<1) will be given if the candidate’s

decision concurs with the minority of the panel. The

candidate will score a ‘0’ if no panellist chooses this

option.3 The formula to calculate the weighted scores

is shown in Table 2.

There are other scoring methods reported in

the literature where a consensus-based single-answer

scoring method or 3-point Likert scale scoring

method is employed to determine the candidate

scores.4 17

Selecting the reference panel

In general, a panel of 10 to 15 expert members

relevant to the discipline is recommended to produce

credible and reliable scores.18 The inter- and intra-rater

reliability in the SCT panel have been shown to

be good.19

The composition of the panel should include

clinical teachers and academics who are familiar

with the curriculum and experts in the field relevant

to the discipline tested. Studies have shown that

using general practitioners (GPs) in the panel may

produce similar mean scores to specialists but with a

wider standard deviation.3

A recent study, however, raised concerns about

the reference standard and judgement of the expert

panel. The study compared 15 emergency medicine

consultants’ judgement scores with evidence-based

likelihood ratios. The results showed that 73.3%

of the mean judgement was significantly different

to the corresponding likelihood ratios, with 30%

overestimation, 30% underestimation, and 13.3%

with diagnostic values in the opposite direction.20

Other studies raised concerns about the possibility

of outdated clinical knowledge and cognitive bias in

the experts’ decision-making.21 22 Evidence of context

specificity has also been highlighted whereby the

agreement between SCT scores derived using

different scoring keys with expert reference panels

from a different context (hospitals and specialty) was

poor.23

Implementation of script concordance test in formative and summative assessments

The structure and layout of the SCT questions can

easily be implemented in the usual pen and paper-based

or online electronic format. Candidates

answer each question (with five options) using a

standardised answer sheet to facilitate computer

scanning and scoring or directly online using the

computer.

It is often difficult to get busy clinicians to

meet together face-to-face to answer the questions.

By uploading the questions online, the panellists

can attempt them anytime and make the questions

available through a secure online platform. The

response data can then be collated and the weighted

scores for responses on each score scale calculated.3

After capturing the candidates’ responses for

all items, scoring of responses for each question

can then be performed using the formula described

above. This will ensure a rapid turnaround time that

will be very effective in the assessment process.

For formative assessment purposes, expert

panel consensus scores are provided to the

candidates, followed by expert clinicians explaining

and discussing the options in each scenario with

the candidates for constructive feedback. Script

concordance test can also be used to identify

borderline students with suboptimal clinical

reasoning skills for appropriate remedial measures

such as bedside teaching, tutorials, or clinical

simulations.24

For summative assessment purposes,

particularly where there is not a large pool of SCT

items, it is important to avoid constructing irrelevant

variance in SCT scores, by not releasing or discussing

post-examination, the expected responses (based on

expert panel’s responses), and the associated score

for each of the answer options in SCT items.

Unlike MCQ where there is only one single

best answer that candidates could memorise and

disseminate after the examination, the partial credit

scoring model applied in SCT, where multiple

answer options are accepted and each carries a

fraction or all of the allocated mark, has to a certain

extent rendered sharing of ‘correct’ answers after the

examination difficult.

Developing quality script concordance test questions

Each clinical scenario has to be authentic and

the presentation represents a realistic clinical

encounter that is relevant to the specific discipline,

preferably with a certain degree of uncertainty. The

new information presented needs to stimulate the

candidate to re-consider and re-evaluate how that

particular piece of new information will affect the

likelihood of the initial diagnosis, or appropriateness

of initial planned investigation or management

option. This will ensure the content validity in the

SCT questions.

Particular care should be taken to develop

options that will attract the full range of the five

options available for the candidate to choose from. In

other words, the additional pieces of new information

should result in the consideration of -2 and +2 as well

as -1, 0, and +1 options. A test-wise candidate might

choose to consider only the options of -1, 0 and +1 if

they notice that most panel consensus answers with

a full score of 1 mark usually fall within these three

options rather than also covering the -2 and +2.25 As

a result, developing good-quality SCT questions is

not easy. Care should be taken to develop clinical

scenarios that do not focus solely on factual recall

but involve a reasoning process with elements of

uncertainty that will likely attract responses that

spread across the 5-point Likert scale.26

Reliability and validity of script concordance test as an assessment tool

The reliability of SCT as an assessment tool has been

investigated.2 6 A 60- to 90-minute examination will

produce a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.70 to 0.85.7 25 27 28 There

are concerns, however, about inter-panellist errors

in SCT; the use of Cronbach’s alpha in measuring the

reliability of the test where partial credit model of

scoring is used, ie multiple options/responses are

awarded either a full or fraction of allocated mark;

and case scenarios that could create inconsistencies

among items.

As an assessment tool, SCT has been shown

to be valid in assessing clinical reasoning.13 14 19 28

Studies have shown that SCT scores correlate well

with other assessment scores from the clinical years

of the candidates.2

The construct validity of SCT questions can

be examined by correlating the scores with the

level of training to predict future performance on

clinical reasoning. A recent study has compared the

progression of clinical reasoning skills of medical

students with those of a group of practising GPs who

are also their Problem Based Learning group tutors.29

Another study showed that there was a statistically

significant gain in SCT performance over a 2-year

period in two different cohorts of medical students

using the same set of 75-item SCT.26 There was

significant progression of clinical reasoning skills

from medical students at the novice level through

to practising GP clinicians, reflected by the higher

scores in the GP group attempting the SCT questions.

Empirical evidence supporting the construct

validity based on progression of SCT scores with

clinical experience from undergraduate students to

postgraduate training has also been reported.2 5 24 30 31

The construct validity of SCT has been questioned

because of the logical inconsistencies as a result

of partial credit scoring methodology making it

possible for a hypothesis to be simultaneously more

likely and less likely.32 Nonetheless, a certain degree

of variability in panel scores has been shown to be a

key determinant of the discriminatory power of the

test and allows richness of thinking about clinical

cases.33 34 Another study found that 27% of residents

in one SCT administration scored above the expert

panel’s mean, which may indicate issues with the

construct validity, particularly in the credibility and

validity of the scoring key and hence the resulting

SCT scores interpretation.33

Test-wise candidates would select the answers

to be around ‘0’ rather than ‘-2’ or ‘+2’ if they noticed

that most panellist scores did not fall in the ‘extreme’

(-2 or +2) range due to the construct of the SCT

questions and options. This could be avoided by

first using the option descriptor of “much less likely

(-2)” and “much more likely (+2)” rather than “ruling

out the diagnosis” and “almost certain/definite

diagnosis” as described in the format of SCT section

above.19 Second, when collating the SCT questions

into an examination paper, one could select a

relatively equal number of items with both ‘extreme’

answers as well as median answers. Recent data

have shown that by employing the above strategies

in developing the paper, candidates who chose ‘0’ for

all the questions would score only around 25% in

the SCT examination and would gain no advantage

(unpublished data). This is in contrast to the finding

of another study wherein candidates who chose

the midpoint scale (‘0’) performed better than the

average candidate.32

The correlation of SCT scores with other

modalities of assessment would be expected to

be low as SCT is designed to measure clinical

reasoning rather than factual or knowledge recall.

The correlation coefficient between SCT and MCQ

was poor (r=0.22), and that between SCT and extended matching

questions (EMQ) was 0.46.4

Collating and moderating the expert reference panellist responses

In collating the SCT questions for use in a summative

examination, appropriate clinical scenarios/vignettes with the related diagnoses, investigations,

and management should be selected according to

the blueprint of the assessment. The clinical topics

should have a good spread and represent core areas

of learning that are relevant to the curriculum and

appropriate to the level of training of the candidates.

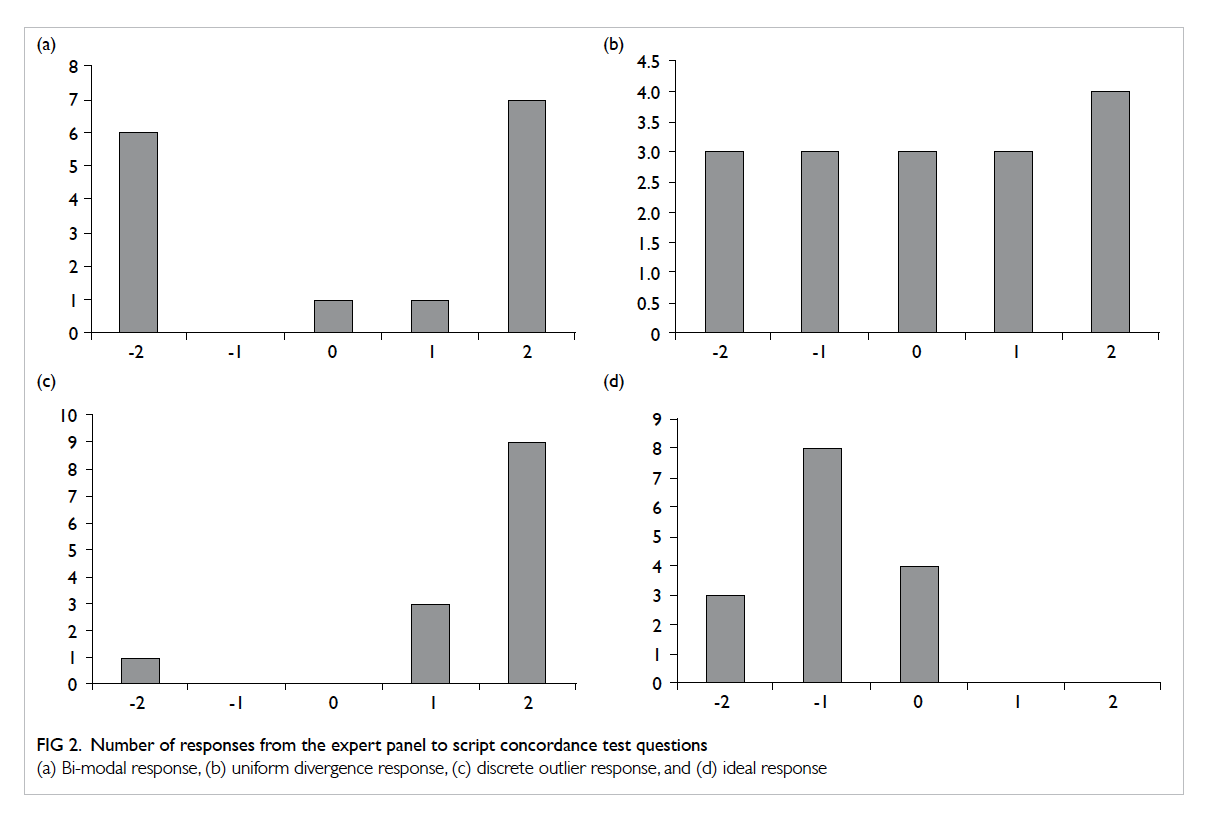

In reviewing the expert panel responses to

each question, bi-modal and uniform divergence

responses should trigger a detailed scrutiny of the

clinical vignette and the options. In the case of bi-modal

response (Fig 2a), the panel has an equal split of the best option between -2 and +2. This usually

results from an error in the question or a controversial

investigation or management option with discordant

‘expert opinions’. A modification of the question and

re-scoring will usually solve this issue. If re-scoring

results in the same bi-modal response, the question

should be discarded for scoring in the examination.

In the case of uniform divergence responses (Fig 2b), there is an equal spread in the number of

members choosing all the five options. This usually

signifies a non-discriminating question and the

item should again be discarded. A discrete outlier

response (Fig 2c) usually represents an error in the particular panellist’s decision or ‘clicking the wrong

answer accidentally’ when the member should have

answered -2 instead of +2. The ideal pattern would

be relatively close convergence with some variation

(Fig 2d).3

Figure 2. Number of responses from the expert panel to script concordance test questions

(a) Bi-modal response, (b) uniform divergence response, (c) discrete outlier response, and (d) ideal response

As mentioned previously, the set of questions

in the SCT examination should be selected in such

a way that there are similar numbers of full marks

in each option across the five options. This will

avoid the test-wise candidates being advantaged by

selecting only the -1, 0, or +1 options and avoiding

the extreme options of -2 and +2.3 By employing this

strategy to select questions that cover the full 5-point

Likert scale, test-wise students will only score 25%

in the SCT examination if they choose the response

of ‘0’ for all questions (unpublished data) compared

with 57.6% in another cohort sitting a SCT test

without the specific question selection process.32

Standard setting the pass/fail cutoff score

In setting the pass/fail cutoff score of the SCT

questions, the expert panels’ mean scores and

standard deviations are chosen to guide the process.

This is calculated by asking all the members of the

panel to attempt the same set of SCT questions and

their responses are then scored accordingly. The

borderline score of the undergraduate students is

usually set at 3 to 4 standard deviations below the

expert panel’s mean score.3 35 Studies have shown

that using recent graduates or fellows in training

might result in a mean score that is closer to the

students’ mean and therefore a smaller number of

standard deviations would be more appropriate.3

Other methods of standard setting include

using the single correct answer method.29 36 Standard

setting of a pass/fail cutoff score is an area that

warrants ongoing research to inform and improve

the practice of using SCT as a summative assessment

tool for clinical data interpretation and decision-making

skills.

The use of script concordance test in the Asia-Pacific region and its limitations

Examinations using SCT have been successfully

implemented in the school-entry medical schools in

Indonesia, Singapore, Taiwan, and Australia3 7 36 37; and

in graduate-entry medical schools in Australia.29 38

Such test has the potential to supplement MCQ and

SAQ to test the higher-order thinking of medical

candidates to allow a more robust overall written

assessment in the assessment programme. In fact,

SCT is one of the few currently available assessment

tools for clinical reasoning in a written format.28 It

can be implemented relatively easily in the paper-based

format or online. Initial pilot examinations can

be set as a formative exercise to enhance candidates’

feedback and learning.24 Further collaboration

with other institutions to develop, score, and share

question items can ensure effective and efficient

delivery of such examinations.

Limitations to the widespread usage of SCT

could be due to: difficulties in developing good-quality

SCT clinical scenarios, concerns about the

validity of the test, recruiting a sufficient number of

appropriate expert clinicians for the reference panel,

lack of a general consensus in setting the borderline

pass mark, and the candidates’ familiarity with the

question format.3 24 25 28 32 34

Conclusions

This article attempts to review the current

use of SCT in assessing clinical reasoning and

data interpretation skills in undergraduate and

postgraduate medicine. The empirical evidence

reported for the reliability and validity of SCT

scores from existing literature seems encouraging.

Approaches to develop quality items, moderation

of expert panel scoring and these post-hoc quality

assurance measures, and optimisation of scoring

scale will to a certain extent mitigate the threat

to the validity of SCT score interpretation and

its use for summative examination purposes.

Combining SCT (testing the clinical reasoning and

data interpretation skills with authentic written

simulations of ill-defined clinical problems set at the

‘knows how’ level) with MCQ/SAQ/EMQ (testing

the ‘knows’ and ‘knows how’), objective structured

clinical examination (testing ‘shows how’), and

workplace-based assessment (testing the ‘does’) in

the medical curriculum will enhance the robustness

and the credibility of the assessment programme.

Further research into the use of SCT in both

undergraduate and postgraduate medical education

is warranted, particularly on standard setting for the

pass/fail cutoff score and best practices that may

help reduce the threat to the validity of SCT scores.

References

1. Charlin B, Roy L, Brailovsky C, Goulet F, van der Vleuten C.

The Script Concordance test: a tool to assess the reflective

clinician. Teach Learn Med 2000;12:189-95. Crossref

2. Carrière B, Gagnon R, Charlin B, Downing S, Bordage

G. Assessing clinical reasoning in pediatric emergency

medicine: validity evidence for a Script Concordance Test.

Ann Emerg Med 2009;53:647-52. Crossref

3. Duggan P, Charlin B. Summative assessment of 5th year

medical students’ clinical reasoning by Script Concordance

Test: requirements and challenges. BMC Med Educ

2012;12:29. Crossref

4. Kelly W, Durning S, Denton G. Comparing a script

concordance examination to a multiple-choice examination

on a core internal medicine clerkship. Teach Learn Med

2012;24:187-93. Crossref

5. Lubarsky S, Chalk C, Kazitani D, Gagnon R, Charlin B.

The Script Concordance Test: a new tool assessing clinical

judgement in neurology. Can J Neurol Sci 2009;36:326-31. Crossref

6. Meterissian S, Zabolotny B, Gagnon R, Charlin B. Is the

script concordance test a valid instrument for assessment

of intraoperative decision-making skills? Am J Surg

2007;193:248-51. Crossref

7. Soon D, Tan N, Heng D, Chiu L, Madhevan M. Neurologists

vs emergency physicians: reliability of a neurological script

concordance test in a multi-centre, cross-disciplinary

setting. Neurology 2014;82(10 Suppl):327.

8. Talvard M, Olives JP, Mas E. Assessment of medical

students using a script concordance test at the end of their

internship in pediatric gastroenterology [in French]. Arch

Pediatr 2014;21:372-6. Crossref

9. Miller GE. The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance. Acad Med 1990;65(9 Suppl):S63-7. Crossref

10. Mehay R. The essential handbook for GP training and

education. Chapter 29. Assessment and competence.

Available from: http://www.essentialgptrainingbook.com/chapter-29.php. Accessed 10 May 2015.

11. Foucault A, Dubé S, Fernandez N, Gagnon R, Charlin

B. Learning medical professionalism with the online

concordance-of-judgment learning tool (CJLT): A pilot

study. Med Teach 2014 Oct 22:1-6. Epub ahead of print. Crossref

12. Schmidt HG, Norman GR, Boshuizen HP. A cognitive

perspective on medical expertise: theory and implications.

Acad Med 1990;65:611-21. Crossref

13. Lubarsky S, Charlin B, Cook DA, Chalk C, van der Vleuten

CP. Script concordance testing: a review of published

validity evidence. Med Educ 2011;45:329-38. Crossref

14. Brazeau-Lamontagne L, Charlin B, Gagnon R, Samson

L, Van Der Vleuten C. Measurement of perception and

interpretation skills during radiology training: utility of the

script concordance approach. Med Teach 2004;26:326-32. Crossref

15. Collard A, Gelaes S, Vanbelle S, et al. Reasoning versus

knowledge retention and ascertainment throughout

a problem-based learning curriculum. Med Educ

2009;43:854-65. Crossref

16. Lineberry M, Kreiter CD, Bordage G. Script concordance

tests: strong inferences about examinees require stronger

evidence. Med Educ 2014;48:452-3. Crossref

17. Williams RG, Klamen DL, White CB, et al. Tracking

development of clinical reasoning ability across five medical

schools using a progress test. Acad Med 2011;9:1148-54. Crossref

18. Gagnon R, Charlin B, Coletti M, Sauvé E, van der Vleuten

C. Assessment in the context of uncertainty: how many

members are needed on the panel of reference of a script

concordance test? Med Educ 2005;39:284-91. Crossref

19. Dory V, Gagnon R, Vanpee D, Charlin B. How to construct

and implement script concordance tests: a systematic

review. Med Educ 2012;46:552-63.

20. Ahmadi SF, Khoshkish S, Soltani-Arabshahi K, et al.

Challenging script concordance test reference standard

by evidence: do judgments by emergency medicine

consultants agree with likelihood ratios? Int J Emerg Med

2014;7:34. Crossref

21. Ramos K, Linscheid R, Schafer S. Real-time information-seeking

behavior of residency physicians. Fam Med

2003;35:257-60.

22. Norman GR, Eva KW. Diagnostic error and clinical

reasoning. Med Educ 2010;44:94-100. Crossref

23. Tan N, Tan K, Ponnamperuma G. Expert clinical

reasoning is not just local but hyperlocal—insights into

context specificity from a multicentre neurology script

concordance test. Neurology 2015;84(14P4):191.

24. Ducos G, Lejus C, Sztark F, et al. The Script Concordance

Test in anesthesiology: Validation of a new tool for

assessing clinical reasoning. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med

2015;34:11-5. Crossref

25. See KC, Tan KL, Lim TK. The script concordance test for

clinical reasoning: re-examining its utility and potential

weakness. Med Educ 2014;48:1069-77. Crossref

26. Humbert AJ, Miech EJ. Measuring gains in the clinical

reasoning of medical students: longitudinal results

from a school-wide script concordance test. Acad Med

2014;89:1046-50. Crossref

27. Gagnon R, Charlin B, Lambert C, Carrière B, Van der

Vleuten C. Script concordance testing: more cases or more

questions? Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 2009;14:367-75. Crossref

28. Nouh T, Boutros M, Gagnon R, et al. The script

concordance test as a measure of clinical reasoning: a

national validation study. Am J Surg 2012;203:530-4. Crossref

29. Wan SH. Using Script Concordance Testing (SCT) to

assess clinical reasoning—the progression from novice to

practising general practitioner. Proceedings of the 11th

Asia Pacific Medical Education Conference; 2014 Jan

15-19; Singapore.

30. Charlin B, van der Vleuten C. Standardized assessment in

contexts of uncertainty: The script concordance approach.

Eval Health Prof 2004;27:304-19. Crossref

31. Lambert C, Gagnon R, Nguyen D, Charlin B. The script

concordance test in radiation oncology: validation study

of a new tool to assess clinical reasoning. Radiat Oncol

2009;4:7. Crossref

32. Lineberry M, Kreiter C, Bordage G. Threats to validity

in the use and interpretation of script concordance test

scores. Med Educ 2013;47:1175-83. Crossref

33. Charlin B, Gagnon R, Lubarsky S, et al. Assessment in the

context of uncertainty using the script concordance test:

more meaning for scores. Teach Learn Med 2010;22:180-6. Crossref

34. Lubarsky S, Gagnon R, Charlin B. Scoring the Script

Concordance Test: not a black and white issue. Med Educ

2013;47:1159-61. Crossref

35. Wan SH, Clarke R. Using a clinician panel to set the

borderline mark for Script Concordance Testing (SCT) to

assess clinical reasoning for graduating medical candidates.

Proceedings of the 8th International Medical Education

Conference; 2013 March 13-15; Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

36. Irfannuddin I. Knowledge and critical thinking skills

increase clinical reasoning ability in urogenital disorders:

a Universitas Sriwijaya Medical Faculty experience. Med J

Indonesia 2009;18:53-9. Crossref

37. Tsai TC, Chen DF, Lei SM. The ethics script concordance

test in assessing ethical reasoning. Med Educ 2012;46:527. Crossref

38. Ingham AI. The great wall of medical school: a comparison

of barrier examinations across Australian medical schools.

Aus Med Student J 2011;2:5-8.