DOI: 10.12809/hkmj144414

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Acquired localised hypertrichosis in a Chinese child after cast immobilisation

MW Yuen, MB, ChB;

Loretta KP Lai, MFM, FHKAM (Family Medicine);

PF Chan, MOM, FHKAM (Family Medicine);

David VK Chao, FRCGP, FHKAM (Family Medicine)

Department of Family Medicine and Primary Health Care, Kowloon East Cluster, Hospital Authority, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr MW Yuen (ymw847@ha.org.hk)

Abstract

Hypertrichosis refers to excessive hair growth that is

independent of any androgen effect. Hypertrichosis

could be congenital or acquired, localised or

generalised. The phenomenon of acquired localised

hypertrichosis following cast application for a

fracture is well known to orthopaedic surgeons, but

is rarely encountered by primary care physicians.

We describe a 28-month-old Chinese boy who

had fracture of right leg as a result of an injury. He

had a cast applied by an orthopaedic surgeon as

treatment. On removal of the cast 6 weeks later, he

was noticed to have significant hair growth on his

right leg compared with the left leg. The patient

was reassessed 3 months after removal of the cast.

The hypertrichosis resolved completely with time.

This patient was one of the youngest among the

reported cases of acquired localised hypertrichosis

after cast application. We illustrate the significance

of management of post-cast–acquired localised

hypertrichosis in the primary care setting.

Introduction

Hair growth pattern in humans depends on age,

sex, and race.1 Hypertrichosis refers to excessive

hair growth that is inappropriate for a patient

after consideration of the normal variation of

an individual’s reference group.2 Hypertrichosis

is different from ‘hirsutism’, which is caused

by excessive androgen-sensitive hair growth.1

Hypertrichosis can be categorised into congenital

versus acquired and generalised versus localised,

and it may cause considerable psychological stress.3

Acquired localised hypertrichosis (ALH) following

a fracture or cast application has been reported in

different countries. In this case report, a Chinese boy

with localised hypertrichosis in the right leg after

application of a cast following right leg fracture is

described. To the best of our knowledge, this patient

represents one of the youngest reported cases.

Case report

In January 2014, a 28-month-old Chinese boy

presented to the general out-patient clinic at Tseung

Kwan O Hospital in Hong Kong with limping gait

after removal of a cast applied for right leg fracture.

During the consultation, the child was observed to

have excessive hair growth on his right leg. He had a

history of right leg fracture 6 weeks previously after

he accidentally fell from a height of 1.5 m. He had

consulted a private orthopaedic surgeon and a cast

was applied for 6 weeks. After removal of the cast,

he was noticed to have a lot of new hair growth on

his right leg. There was no increased hair growth

over the left leg or other body parts. There was no

history of systemic or topical medication use before

the onset of increased hair growth. The mother was

concerned about whether any treatment was needed

for the excessive hair growth.

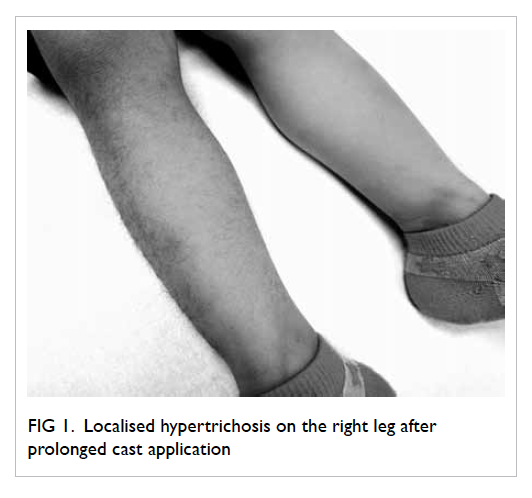

On physical examination, there was

significantly increased thick dark hair growth

over the anterior and lateral parts of the right leg

previously covered by the cast (Fig 1). There was no

other skin change. The new hair growth caused no

skin symptoms to the child. The child walked with a

mild limping gait, but there was no limb deformity,

muscle wasting, or bony tenderness.

The patient was diagnosed with ALH due to

cast application. The patient’s mother was reassured

about the benign, transient, and self-limiting nature

of the condition. His limping gait was treated with

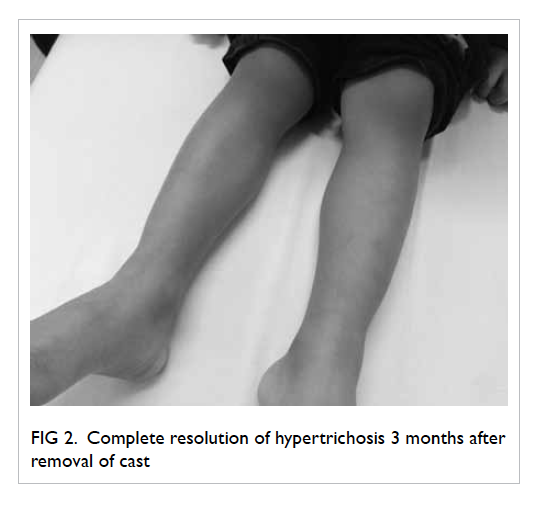

physiotherapy. He was followed up at 3 months,

when his gait had become normal and there was

spontaneous complete resolution of the localised

hypertrichosis (Fig 2).

Discussion

There are many causes of ALH such as chronic

irritation (eg skin overlying areas of thrombophlebitis

or chronic osteomyelitis), friction (eg lichen

simplex chronicus, insect bites, atopic eczema),

or inflammation (eg chemical-induced dermatitis,

ultraviolet irradiation, vaccination sites).2 It is not

uncommon to find ALH following prolonged cast or

splint application for various orthopaedic conditions.

A Turkish study involving 117 patients showed that

post-cast hypertrichosis might occur in up to one

third of patients.4 The study showed that there was

no sex predisposition, but the frequency peaked in

the adolescent age-group.4 Post-cast ALH has been

reported in paediatric and young adult patients

in various countries from 1989 to 2013, but the

prevalence in local Chinese patients is unknown.5 6 7 8 9 10 11

Complete resolution of hypertrichosis was noted at

around 3 to 9 months after removal of the cast or

splint.

One of the major mechanisms of hypertrichosis

is conversion of vellus to terminal hair. Vellus hair is

fine, non-pigmented, and produced by hair follicles

located in the dermis. Vellus hair develops on almost

all parts of the body, and its growth is not affected

by hormones. Terminal hair is thick, pigmented,

and produced by large hair follicles located in the

subcutis. Terminal hair is found on sites where hair

growth is affected by hormones, eg scalp, beard,

axillae, and pubic area.12 Vellus-to-terminal switch

on body sites that usually do not have terminal

hairs will cause hypertrichosis. The underlying

mechanism of this vellus-to-terminal switch is still

poorly understood.13

Another major mechanism of hypertrichosis

involves change in the hair growth cycle. Hair follicles

undergo lifelong cyclic transformation in three

stages: anagen, the active growth phase; catagen,

the apoptosis-driven phase; and telogen, the resting

phase followed by hair shedding.12 Hypertrichosis

results when the hair follicles stay longer than usual

in the anagen phase. Similar to vellus-to-terminal

switch, control of the hair growth cycle is still not

well understood.1

The pathogenesis of post-cast hypertrichosis

after fracture is not well-established and different

hypotheses have been postulated. Some authors

suggested that prolonged cast application provides

an occlusive, moist, and warm environment which,

together with irritation caused by friction, promotes

hair growth.11 Some authors, however, believe that

the increase in regional blood flow to the bone

following fracture provides abundant oxygen and

nutrients that prolong the anagen phase of hair

growth, resulting in transient hypertrichosis.6 This

hypothesis is supported by the speculation that

hypertrichosis has also been observed after splint

application that does not occlude the injured area,

suggesting that the fracture-healing process rather than

the cast-occlusion effect led to hypertrichosis.10

Other hypotheses on the pathogenesis of ALH

include transient cutaneous hyperaemia stimulating

the hair follicles5 and reflex sympathetic dystrophy

induced by immobilisation causing vasodilatation of

the affected area and stimulating hair growth.7

Post-cast ALH is more commonly observed in

children and young adults.4 This could be explained

by age-related changes in hair growth. With ageing,

the activity of the hair follicles declines and the hair

growth rate decreases. Since older adult patients

have a shorter anagen period of the hair growth

cycle, ALH is less frequently observed in this age-group.

Children and young adults do not have this

unfavourable effect of the ageing process on hair

growth to cancel stimulation of hair follicles after

cast application, and therefore post-cast ALH is

more commonly seen in this younger age-group.

Cases of ALH following fracture or cast

application have been described by orthopaedic

surgeons and dermatologists, but not in the

primary care setting. Nonetheless, such cases may

be encountered in primary care. Therefore, family

physicians should be aware of the diagnosis and

management of the condition and its implications

for psychosocial consequences, since hypertrichosis

may cause considerable emotional stress to patients

due to the unsightly cosmetic appearance.10 We

should address any psychological distress brought

about by hypertrichosis and reassure patients

and their parents about the benign and transient

nature of ALH after cast application. In most cases,

the abnormal hair growth will disappear within 6

months, as in this patient, and further investigation

or intervention is not indicated. If, however,

hypertrichosis causes cosmetic or psychological

problems for the patient, hair removal—for example,

by shaving or other mechanical methods—could be

considered.2

References

1. Bertolino A, Freedberg I. Hair. In: Fitzpatrick TB, Eisen AZ,

Wolff K, Freedberg IM, Austen KF, editors. Dermatology in

general medicine. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1993: 671-96.

2. Wendelin DS, Pope DN, Mallory SB. Hypertrichosis. J Am

Acad Dermatol 2003;48:161-79. Crossref

3. Vashi RA, Mancini AJ, Paller AS. Primary generalized

and localized hypertrichosis in children. Arch Dermatol

2001;137:877-84.

4. Akoglu G, Emre S, Metin A, Bozkurt M. High frequency

of hypertrichosis after cast application. Dermatology

2012;225:70-4. Crossref

5. Leung AK, Kiefer GN. Localized acquired hypertrichosis

associated with fracture and cast application. J Natl Med

Assoc 1989;81:65-7.

6. Kara A, Kanra G, Alanay Y. Localized acquired

hypertrichosis following cast application. Pediatr Dermatol

2001;18:57-9. Crossref

7. Rathi SK. Localized acquired hypertrichosis following cast

application. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2007;73:367. Crossref

8. Leung AK, Wong AS. Localized acquired hypertrichosis

associated with the application of a splint. Case Rep Pediatr

2012;2012:592092.

9. Ma HJ, Yang Y, Ma HY, Jia CY, Li TH. Acquired localized

hypertrichosis induced by internal fixation and plaster cast

application. Ann Dermatol 2013;25:365-7. Crossref

10. Harper MC. Localized acquired hypertrichosis associated

with fractures of the arm in young females. A report of two

cases. Orthopedics 1986;9:73-4.

11. Chang CH, Cohen PR. Ipsilateral post-cast hypertrichosis

and dyshidrotic dermatitis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil

1995;76:97-100. Crossref

12. Wolff K, Johnson RA, Saavedra AP. Disorders of hair

follicles and related disorders. In: Fitzpatrick’s color atlas

and synopsis of clinical dermatology. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 760-89.

13. Stenn KS, Paus R. Controls of hair follicle cycling. Physiol

Rev 2001;81:449-94.