Hong Kong Med J 2015 Jun;21(3):261–8 | Epub 22 May 2015

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj144307

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

MEDICAL PRACTICE

Translating evidence into practice: Hong Kong Reference Framework for Preventive Care for

Children in Primary Care Settings

Natalie PY Siu, MB, BS, FHKAM (Family Medicine)1;

LC Too, MB, BS, FHKAM (Family Medicine)1;

Caroline SH Tsang, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Community Medicine)1;

Betty WY Young, MB, BS, FHKAM (Paediatrics)2;

1 Primary Care Office, Department of Health, Hong Kong

2 Clinical Advisory Group on Hong Kong Reference Framework for

Preventive Care for Children in Primary Care Settings, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Caroline SH Tsang (caroline_tsang@dh.gov.hk)

Abstract

There is increasing evidence that supports the close

relationship between childhood and adult health.

Fostering healthy growth and development of

children deserves attention and effort. The Reference

Framework for Preventive Care for Children in

Primary Care Settings has been published by the Task

Force on Conceptual Model and Preventive Protocols

under the direction of the Working Group on Primary

Care. It aims to promote health and prevent disease

in children and is based on the latest research, and

contributions of the Clinical Advisory Group that

comprises primary care physicians, paediatricians,

allied health professionals, and patient groups. This

article highlights the comprehensive, continuing,

and patient-centred preventive care for children

and discusses how primary care physicians can

incorporate the evidence-based recommendations

into clinical practice. It is anticipated that the

adoption of this framework will contribute to

improved health and wellbeing of children.

Introduction

Advances in socio-economic conditions and health

care delivery have contributed to improvement in

child health indices in Hong Kong. For example, the

infant mortality rate in Hong Kong is low by world

standards, decreasing from 9.7 per 1000 live births

in 1981 to 1.5 in 2012. Various problems, however,

continue to affect the health of Hong Kong children.

For instance, the increasing trend of obesity among

primary and secondary school children has become

a major public health concern.1 Injury is also a

significant cause of mortality and morbidity in

children. Many of these problems can be prevented.

In order to adopt the life-course approach to

chronic disease prevention and health promotion,

the Task Force on Conceptual Model and Preventive

Protocols under the Working Group on Primary Care

has identified two age-group–specific preventive

reference frameworks, one of which is the Reference

Framework for Preventive Care for Children in

Primary Care Settings.2 It was developed according to

the latest research evidence and with the support of

the Clinical Advisory Group that comprises primary

care physicians, specialists such as paediatricians,

allied health professionals, and patient groups.

Many medical professionals have difficulty

assimilating rapidly evolving scientific evidence into

their practice. The reference framework provides an

interface between research and practice, and aims

to support health care professionals to promote

health and provide continuing and comprehensive

care for children in the community. It consists of a

core document supplemented by a series of modules

that elaborate on the various domains relevant to

child health. This article highlights a practical use

of this reference framework to improve the delivery

of preventive care to children in the primary care

setting.

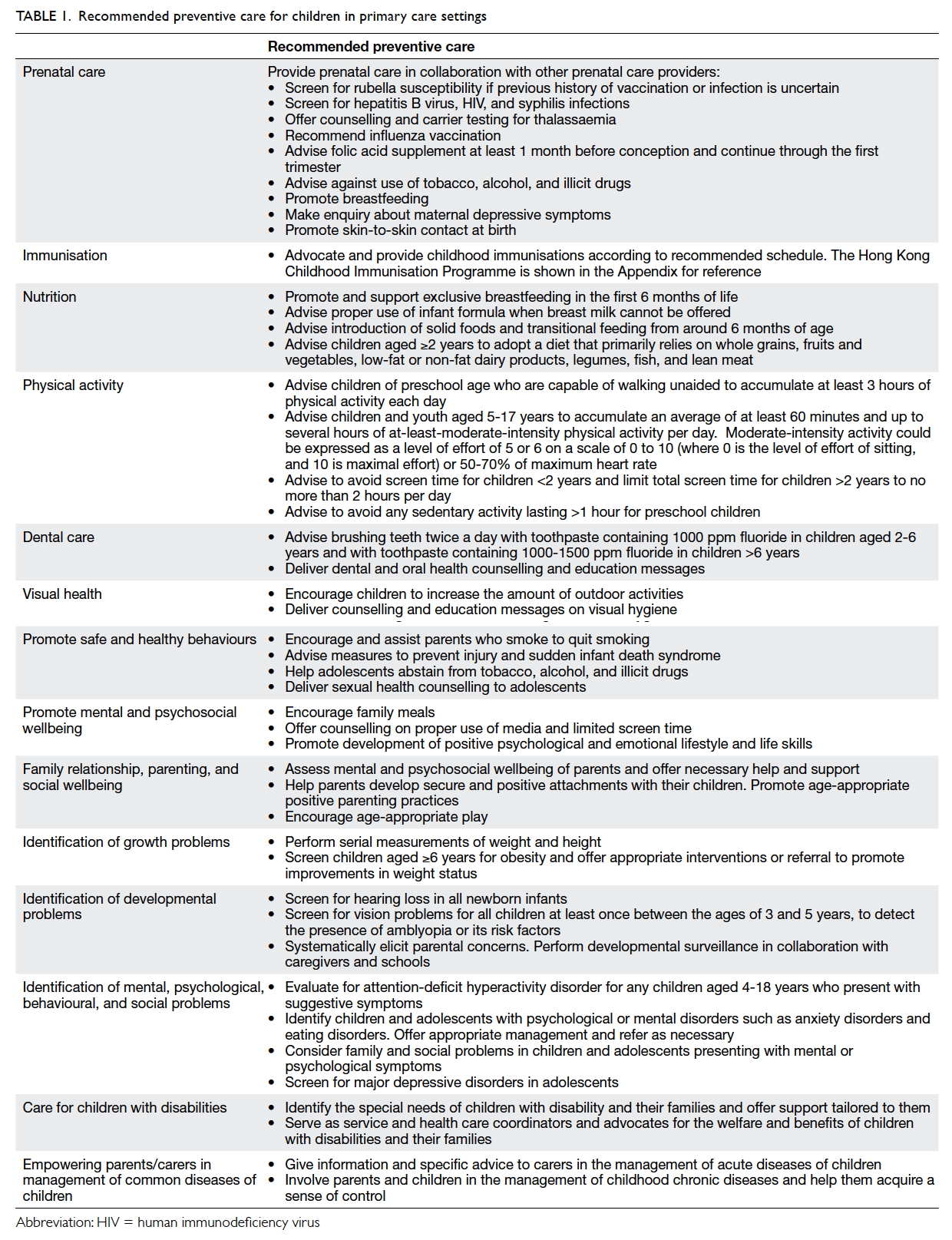

Evidence-based preventive care for children

The core document of the reference framework

provides evidence-based recommendations for

comprehensive preventive care for children and

can be categorised into various health domains,

ranging from prenatal care to care for children

with special needs. Preventive care activities for

children applicable to the primary care setting are

summarised in Table 1.

Continuing and patient-centred preventive care for children

The commitment of primary care physicians to

preventive care of children is vital in the prevention

of disease as well as early detection of problems

and appropriate intervention. Every encounter with

a child and/or the parents/caregivers should be an

opportunity to promote healthy practices. Some

forms of prevention should be delivered regularly,

for example, vaccinations that should adhere to the

locally recommended schedule. Other preventive

care may be offered opportunistically, such as advice

on dental care and physical activity. It is neither

possible nor appropriate to initiate all preventive

care at a single clinic visit. Nevertheless the long-term

relationship between primary care physicians

and patients allows provision of comprehensive and

continuing care.

Practising preventive care for children in primary care

Primary care physicians may not have adequate

time to go through the reference framework,

especially in a busy clinic setting. It is nonetheless

necessary to establish how recommendations of the

reference framework can be applied to patient care.

Four practical tips on application of the reference

framework will be discussed below.

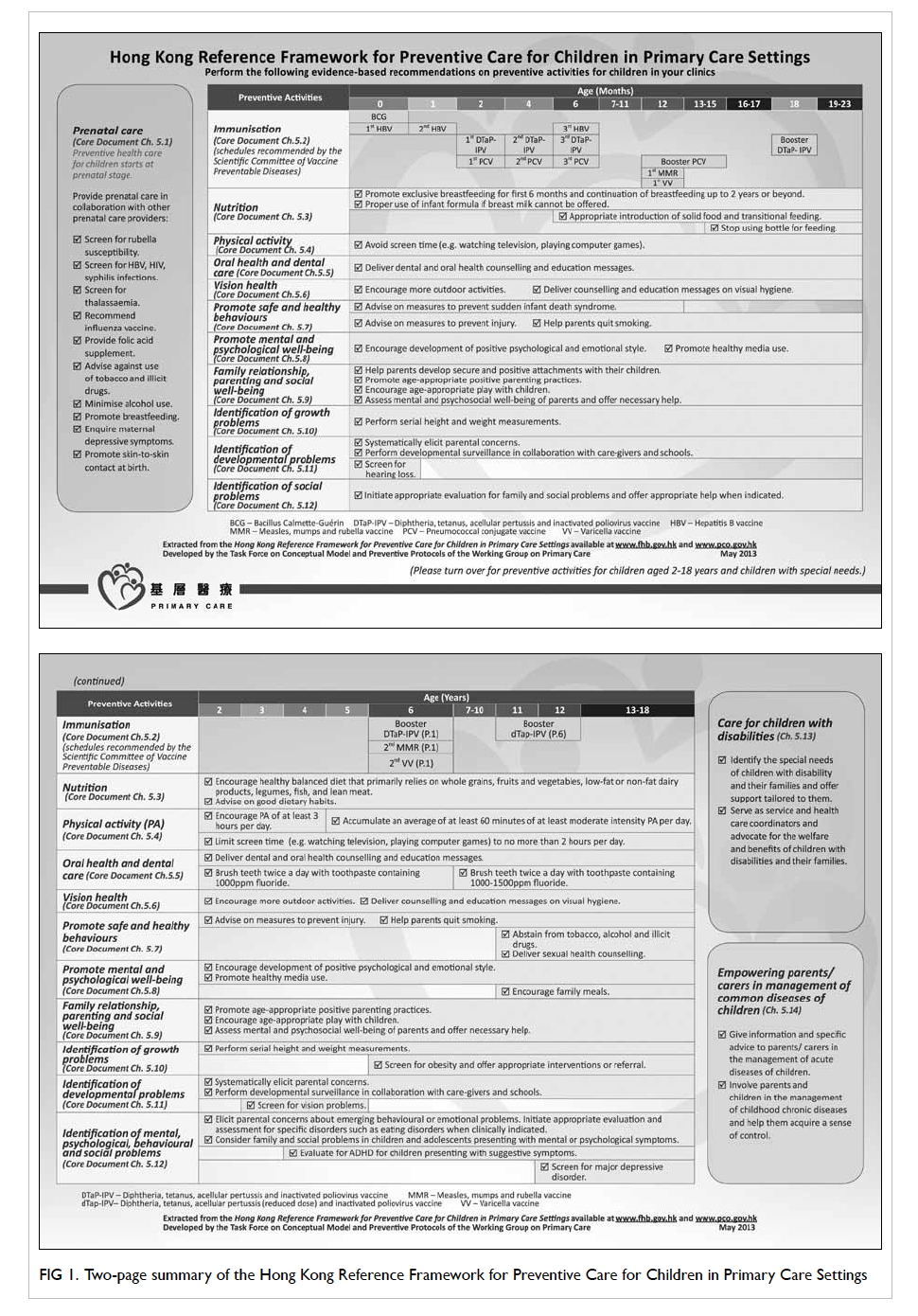

Make use of the two-page summary

The Primary Care Office has developed a two-page

summary that can be downloaded from its

website (Fig 1). Tabulating the various preventive

activities according to age-group will enable primary

care physicians to provide suitable age-specific

preventive measures for their patients. The relevant

chapter of the core document is identified for each

aspect of preventive care, informing the primary

care physician of where to find further information

and supporting evidence. A summary can be posted

on walls or on the desk in primary care consultation

rooms to allow quick reference.

Figure 1. Two-page summary of the Hong Kong Reference Framework for Preventive Care for Children in Primary Care Settings

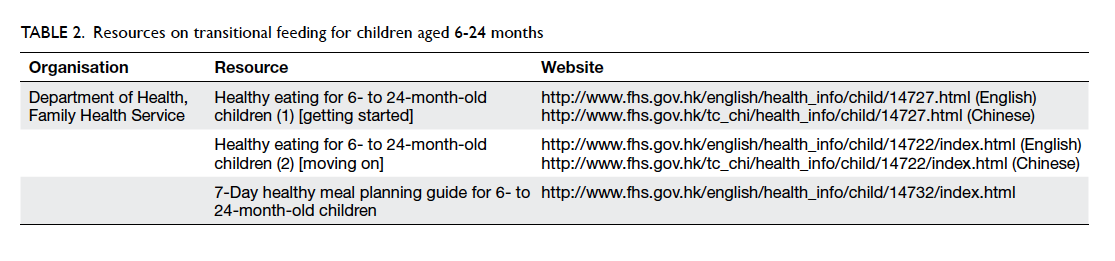

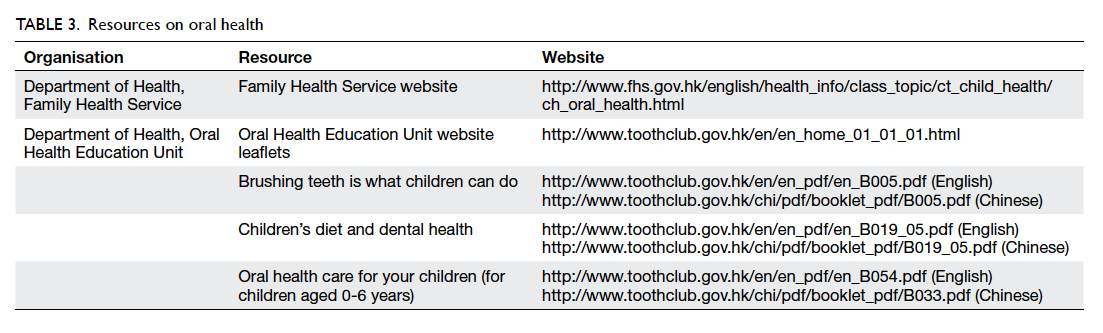

Make use of patient-education materials

Patient-based education interventions, especially

those that involve patient-education material, have

been reported to be effective in the implementation

of clinical practice guidelines.3 Patient-education

materials can also help more effectively deliver

preventive advice. Resources related to the health

care of children, such as transitional feeding (Table

2) and oral health (Table 3), are listed in annex 3 of

the core document. A link to these resources can

be accessed from the electronic version of the core

document. These can be introduced to children and

parents and enhance patient education.

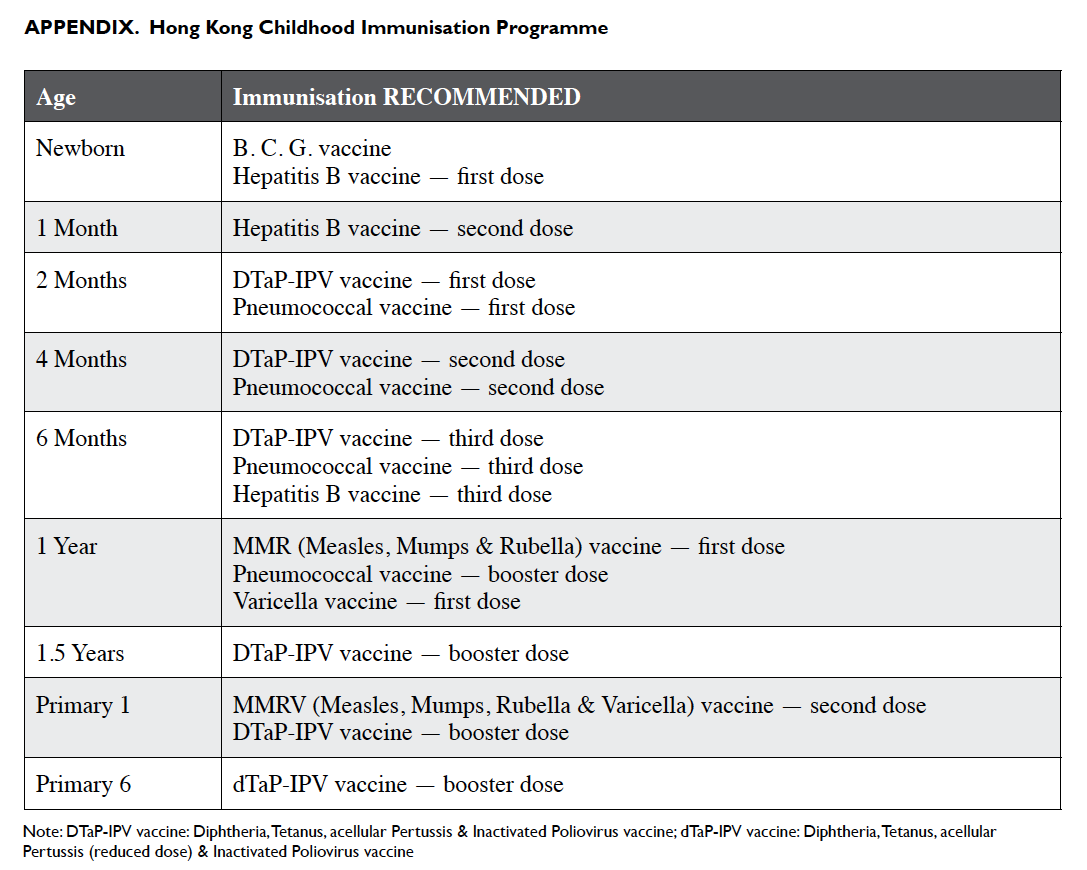

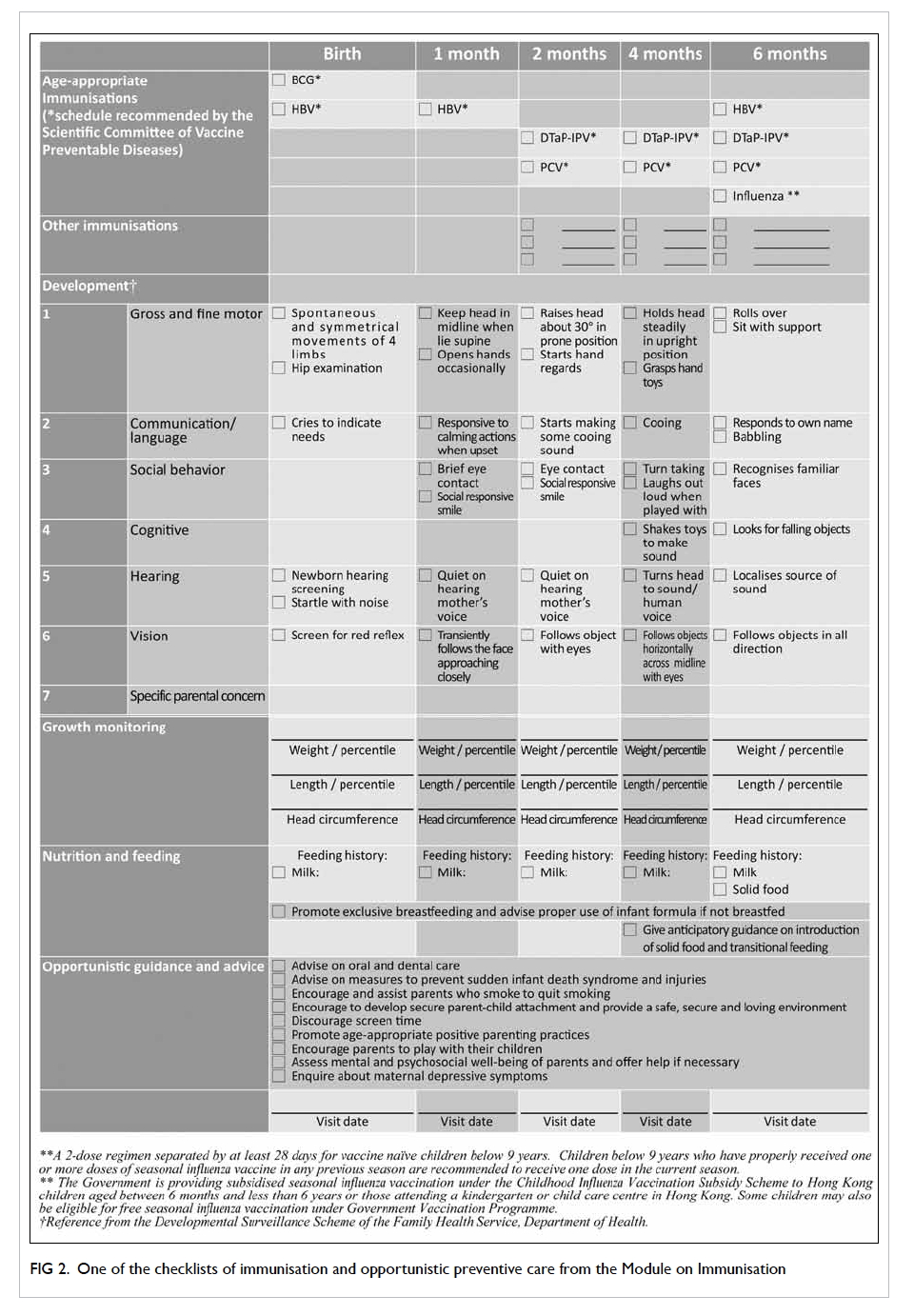

Record preventive care activities using checklists

Embedding guideline evidence into the processes

and documents of patient care can help promote

established evidence-based recommendations.4

Checklists of opportunistic preventive care can

also be incorporated in patient medical records to

allow clear documentation and facilitate any follow-up

care. Primary care physicians can prepare their

own checklists or utilise the ready-made checklists

available in chapter 8 of the Module on Immunisation

(Fig 2).

Figure 2. One of the checklists of immunisation and opportunistic preventive care from the Module on Immunisation

Deliver preventive care according to life stage

Childhood can be considered a sequence of life stages,

namely prenatal, infancy, preschool, school age, and

adolescence. Among the recommendations in Table 1, some items have particular relevance to particular

life stages. For the care of an individual child in the

primary care setting, preventive activities should be

appropriate for age, risk status, and individual needs

and values. Chapter 6 of the core document contains

tables of preventive care for different life stages, and

specifies the timing and action of various activities.

Such a tailored approach to recommendations may

ensure that the research-based message is more

easily translated.5 The practice of preventive care for

different life stages in daily practice can be illustrated

as follows.

Prenatal care

Prenatal care is essential for a healthy outcome of

pregnancy and should commence prior to conception.

All women planning pregnancy should take

daily folic acid supplement at a dose of 400 µg/day

for at least 1 month before conception, and continue

through the first trimester to reduce the risk of

having a baby with neural tube defect.6 7 If the

history of vaccination or infection is uncertain, the

woman should be screened for rubella susceptibility

and, if indicated, rubella vaccine administered 3

months before conception. Influenza vaccination

should also be offered.8 In addition, screening for

hepatitis B virus, human immunodeficiency virus,

and syphilis infections should be offered if it has not

been performed.9 10 11

Due to their harmful effect on fetal growth and

development, women should be questioned about

tobacco and alcohol use, and appropriate counselling

offered.12 13 Breastfeeding should be promoted

with relevant education and support commencing

prenatally.14 15

Infancy (0-24 months of age)

Children and families experience rapid changes

during the period of infancy. Immunisation for

various infectious diseases is vital at this stage. Each

visit of a child to their primary care physician provides

an opportunity to confirm that immunisations are up

to date. Other advice on preventive care can also be

given at the same time, such as promotion of breastfeeding. Primary care providers can refer to the core

document for strategies to promote breastfeeding

and the principles of transitional feeding.

The long-term relationship between primary

care physicians and families allows for surveillance

of a child’s growth and development. Serial

measurements of the weight and length of an infant

should be recorded on a population-specific growth

chart. Routine screening for hearing loss should also

be arranged.

Visits to the primary care physician’s clinic

provide an opportunity to observe relationships

between parents and their children. Secure

parent-child attachment in early childhood can be

protective and provide a foundation for exploration

and normal development.16 Parents can be helped to

understand the concept of attachment and develop

appropriate responses to the attachment behaviours

of their young children. Parents’ psychosocial wellbeing

and parenting capacity should be monitored

and assistance given when indicated.

Preschool (2-5 years of age)

Young children should be provided with a balanced

diet that comprises grains and cereals, vegetables

and meat (including its alternatives, eg fish, poultry,

eggs, beans, etc) in a ratio of 3:2:1 by volume.17

Ongoing surveillance of growth, and

physical and psychosocial development should

be undertaken in partnership with parents.

Screening for vision problems should be offered

for all children aged between 3 and 5 years to

detect amblyopia or the presence of any risk for its

development. Any parental concerns about a child’s

development such as hearing, language, gross and

fine motor development, and social behaviours

should be elicited systematically. Updating a child’s

developmental history by direct questioning of a

parent or carer can assist in the identification of any

abnormalities that warrant further investigation.

Parents should also be asked if they have any concerns

about their child’s behaviour. Testing for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder should be initiated if

academic or behavioural problems and symptoms of

inattention, hyperactivity, or impulsivity are present.

Parenting programmes have been shown to

improve both child behaviour and parenting.18 19 20 21 22 As such, they should be promoted to parents.

Toddlers are prone to injury as they are active

and love to explore their environment. Parents can be

given advice on how to maintain a safe environment

and prevent accidental injury.23

School age (6-12 years of age)

As children grow up, they can be expected to take

on additional responsibility for their health. Healthy

lifestyle advice, such as eating a healthy balanced

diet and taking adequate physical activity, can be

discussed during clinical consultations for episodic

illnesses. It is recommended that children aged 5

years and above be involved in at least 60 minutes

of moderate-to-vigorous–intensity physical activity

each day.24 25 26 Children should minimise sedentary

activity and avoid screen time of more than 2 hours

per day.27 28 29 Differences can be observed in physical

growth among children in this life stage. Screening

for obesity can be offered for children aged 6 years

and older, and appropriate weight maintained by

counselling and behavioural intervention where

indicated.30

School age is the time when learning difficulties

or behavioural problems start to manifest. Primary

care physicians can ask parents about progress at

school and academic performance. Poor school

performance may indicate an underlying learning or

attention disorder. Children should be referred for

detailed assessment if specific learning disabilities

are suspected.

Adolescence (13-18 years of age)

Adolescence is the key transition stage between

childhood and adulthood, a stage of attaining physical

and sexual maturity. Adolescents are curious about

new things and can be subject to peer pressure with

consequent engagement in risk behaviour. When

primary care physicians encounter adolescents, they

have an opportunity to explore their psychosocial

wellbeing. Information can be obtained about

social life and extracurricular activities. Healthy

activities such as sports and outdoor activities and

healthy use of the mass media can be promoted as

appropriate. If adolescents express boredom and loss

of interest in their usual activities, depression should

be suspected. Screening for a major depressive

disorder can be conducted when systems are in

place to ensure accurate diagnosis, psychotherapy,

and follow-up.31

Smoking status for all teenagers should be

established whenever the opportunity arises. Use

of alcohol and illicit drugs should also be assessed

using a non-judgemental approach. Adolescents

who abuse either should be assisted to quit and

referred for further management.32 33 Sexual history can be obtained and preventive counselling on

sexual health issues delivered.34 High-intensity

behavioural counselling is recommended to prevent

sexually transmitted infections in all sexually active

adolescents considered to be at increased risk.

Adolescents and their families should be

encouraged to eat together: frequency of family

meals has been inversely associated with poor

academic performance, depressive symptoms, and

risky behaviour such as tobacco and alcohol use.35

Conclusion

Chronic disease prevention and health promotion

can begin in childhood. Effective delivery of

preventive care to children depends on the

combined efforts of health care professionals, social

workers, teachers, and parents. Through provision

of patient-centred, comprehensive, continuing and

coordinated care, primary care physicians play

a vital role in preventive care for children. The

reference framework provides a common reference

and guidance on a spectrum of preventive care

activities for children. Adoption of the reference

framework, its accompanying two-page summary,

patient-education materials, and preventive care

checklist enhances delivery of care. Practice of

age-appropriate preventive care in different life

stages can improve the health and wellbeing of

children. Primary care physicians are in a privileged

position to incorporate recommendations of the

reference framework into clinical practice, and they

are encouraged to familiarise themselves with the

content of the reference framework. Development of

new modules is underway to provide practical tips

and information about topical issues already featured

in the core document of the reference framework.

Health care professionals are encouraged to visit

the website of the Primary Care Office at www.pco.gov.hk and watch out for the new modules to

be released, as well as information about seminars

related to introduction of the reference frameworks.

Feedback about implementation of the framework is

welcome and will be valuable for revision of the core

document and development of future modules.

References

1. Student Health Service. Newsletter [Internet]. December

2012; 57. Hong Kong SAR: Department of Health.

Available from: http://www.studenthealth.gov.hk/english/newsletters/newsletter_57.html. Accessed 18 Mar 2015.

2. Hong Kong reference framework for preventive care

for children in primary care settings 2012. Available

from: http://www.pco.gov.hk/english/resource/files/ref_framework_children.pdf. Accessed 13 Nov 2014.

3. Davis DA, Taylor-Vaisey A. Translating guidelines into

practice. A systematic review of theoretic concepts,

practical experience and research evidence in the adoption

of clinical practice guidelines. CMAJ 1997;157:408-16.

4. Gerhardt WE, Schoettker PJ, Donovan EF, Kotagal UR,

Muething SE. Putting evidence-based clinical practice

guidelines into practice: an academic pediatric center’s

experience. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2007;33:226-35.

5. Yana R, Jo RM. Getting guidelines into practice: a literature

review. Nurs Stand 2004;18:33-40.

6. Blencowe H, Cousens S, Modell B, Lawn J. Folic acid to

reduce neonatal mortality from neural tube disorders. Int J

Epidemiol 2010;39(Suppl 1):i110-21. Crossref

7. Wolff T, Witkop CT, Miller T, Syed SB; U.S. Preventive

Services Task Force. Folic acid supplementation for

the prevention of neural tube defects: an update of the

evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann

Intern Med 2009;150:632-9. Crossref

8. National Center for Immunization and Respiratory

Diseases. General recommendations on immunization—recommendations of the Advisory Committee on

Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep

2011;60:26-7.

9. Wong VC, Ip HM, Reesink HW, et al. Prevention of the

HBsAg carrier state in newborn infants of mothers who are

chronic carriers of HBsAg and HBeAg by administration

of hepatitis-B vaccine and hepatitis-B immunoglobulin.

Double-blind randomised placebo-controlled study.

Lancet 1984;1:921-6. Crossref

10. Chou R, Smits AK, Huffman LH, Fu R, Korthuis PT; US

Preventive Services Task Force. Prenatal screening for HIV:

A review of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services

Task Force. Ann Intern Med 2005;143:38-54. Crossref

11. Wolff T, Shelton E, Sessions C, Miller T. Screening for

syphilis infection in pregnant women: evidence for

the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force reaffirmation

recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med

2009;150:710-6. Crossref

12. Lumley J, Chamberlain C, Dowswell T, Oliver S, Oakley

L, Watson L. Interventions for promoting smoking

cessation during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

2009;(3):CD001055. Crossref

13. Whitlock EP, Polen MR, Green CA, Orleans T, Klein J;

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Behavioral counseling

interventions in primary care to reduce risky/harmful

alcohol use by adults: a summary of the evidence for the

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med

2004;140:557-68. Crossref

14. Britton C, McCormick FM, Renfrew MJ, Wade A, King SE.

Support for breastfeeding mothers. Cochrane Database

Syst Rev 2007;(1):CD001141. Crossref

15. Chung M, Raman G, Trikalinos T, Lau J, Ip S. Interventions

in primary care to promote breastfeeding: an evidence

review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann

Intern Med 2008;149:565-82. Crossref

16. Greenberg MT, Speltz ML, DeKlyen M. The role of

attachment in the early development of disruptive behavior

problems. Dev Psychopathol 1993;5:191-213. Crossref

17. Department of Health, HKSARG. The healthy eating food

pyramid—a guide to a balanced diet. Available from: http://www.cheu.gov.hk/eng/info/2plus3_12.htm. Accessed Mar

2015.

18. Thomas R, Zimmer-Gembeck MJ. Behavioral outcomes

of Parent-Child Interaction Therapy and Triple P-Positive

Parenting Program: a review and meta-analysis. J Abnorm

Child Psychol 2007;35:475-95. Crossref

19. Nowak C, Heinrichs N. A comprehensive meta-analysis

of Triple P-Positive Parenting Program using hierarchical

linear modeling: effectiveness and moderating variables.

Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 2008;11:114-44. Crossref

20. de Graaf I, Speetjens P, Smit F, de Wolff M, Tavecchio L.

Effectiveness of the Triple P Positive Parenting Program

on behavioral problems in children: a meta-analysis. Behav

Modif 2008;32:714-35. Crossref

21. Effective strategies to support positive parenting in

community health centers: Report of the Working Group

on Child Maltreatment Prevention in Community Health

Centers. Washington, DC: American Psychological

Association; 2009.

22. Centre for Excellence and Outcomes in Children and

Young People’s Services. Improving children’s outcomes by

supporting parental physical and mental health. London:

Department for Education; 2011.

23. Clamp M, Kendrick D. A randomised controlled trial of

general practitioner safety advice for families with children

under 5 years. BMJ 1998;316:1576-9. Crossref

24. Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Report.

Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human

Services; 2008.

25. Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health.

Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010.

26. Janssen I, Leblanc AG. Systematic review of the health

benefits of physical activity and fitness in school-aged

children and youth. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2010;7:40. Crossref

27. Get up & grow: healthy eating and physical activity for

early childhood. Australia: Department of Health and

Aging; 2009. Available from: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/publications/publishing.nsf/Content/gug-carer-toc.

Accessed Mar 2015.

28. UK physical activity guideline. UK Department

of Health. Available from: http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_127931. Accessed

Mar 2015.

29. Guidelines for Preventive Activities in General Practice. 7th

ed. The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners;

2009.

30. US Preventive Services Task Force, Barton M. Screening

for obesity in children and adolescents: US Preventive

Services Task Force recommendation statement. Pediatrics

2010;125:361-7. Crossref

31. Williams SB, O’Connor EA, Eder M, Whitlock EP.

Screening for child and adolescent depression in primary

care settings: a systematic evidence review for the US

Preventive Services Task Force. Pediatrics 2009;123:e716-35. Crossref

32. Supporting smoking cessation: a guide for health

professionals. South Melbourne: The Royal Australian

College of General Practitioners; 2011.

33. American Academy of Pediatrics: Committee on Substance

Abuse. Alcohol use and abuse: a pediatric concern. Pediatrics 2001;108:185-9. Crossref

34. Preventive services for children and adolescents. 16th ed.

Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement; 2010.

35. Eisenberg ME, Olson RE, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Bearinger LH. Correlations between family meals and psychosocial well-being among adolescents. Arch Pediatr

Adolesc Med 2004;158:792-6. Crossref