Hong Kong Med J 2015 Apr;21(2):165–71 | Epub 27 Feb 2015

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj144469

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

MEDICAL PRACTICE CME

Falls prevention in the elderly: translating evidence into practice

James KH Luk, FHKCP, FHKAM (Medicine)1; TY Chan, FHKCP, FHKAM (Medicine)2; Daniel KY Chan, MD, FRACP3

1Department of Medicine and Geriatrics, Fung Yiu King Hospital, Hong Kong

2Department of Medicine and Geriatrics, Kwong Wah Hospital, Yaumatei, Hong Kong

3Faculty of Medicine, University of New South Wales, Ingham Institute; Aged Care & Rehab, Bankstown Hospital, Australia

Corresponding author: Dr James KH Luk (lukkh@ha.org.hk)

Abstract

Falls are a common problem in the elderly. A common

error in their management is that injury from the fall

is treated, without finding its cause. Thus a proactive

approach is important to screen for the likelihood of

fall in the elderly. Fall assessment usually includes a

focused history and a targeted examination. Timed

up-and-go test can be performed quickly and is able

to predict the likelihood of fall. Evidence-based fall

prevention interventions include multi-component

group or home-based exercises, participation in

Tai Chi, environmental modifications, medication

review, management of foot and footwear problems,

vitamin D supplementation, and management of

cardiovascular problems. If possible, these are

best implemented in the form of multifactorial

intervention. Bone health enhancement for

residential care home residents and appropriate

community patients, and prescription of hip

protectors for residential care home residents are

also recommended. Multifactorial intervention

may also be useful in a hospital and residential

care home setting. Use of physical restraints is not

recommended for fall prevention.

Introduction

Falls and imbalance occur commonly in the elderly

and fall/instability is indeed one of the ‘giants’ in

geriatric medicine.1 A fall is often defined as an event

that results in the patient or a body part of the patient

coming to rest inadvertently on the ground or other

surface lower than the body.2 In Hong Kong, the

prevalence in the elderly of having at least one fall in

the preceding 12 months is between 18% and 19.3%,

with 75.2% sustaining injuries and 7.2% having a

serious injury.3 4 Those who fall have significantly

more hospitalisations and clinic visits as well as

accident and emergency department visits than

those who do not. Fear of falling, loss of confidence

in walking, social isolation, and depression can also

occur. Fall is a predictor for decreased functional

state and risk factor for institutionalisation,5 and

the elderly who are prone to falling consume more

health care resources than non-fallers each year.6

Pitfalls in fall management

Despite the potentially severe consequences of

falls, under-reporting by the elderly is common.7

Individuals may attribute falling to the ageing

process or they may not report falls because of the

fear of being restricted in their activities or being

institutionalised following a fall. Some older people,

especially those with cognitive impairment, may

forget the event and consequently fail to inform the

health care team. Alternatively, in the absence of an

obvious injury, physicians may be unaware of falls.

A drawback to the management of falls is that the

consequences, such as fractures or head injuries, are

treated without finding the cause of the fall. Unless

all the underlying risk factors are addressed, falls are

very likely to recur.

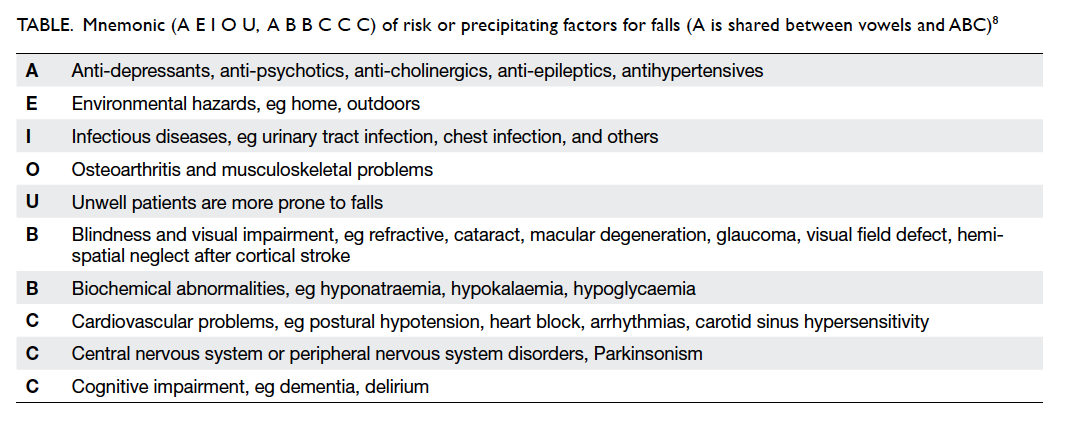

Knowing the risk/precipitating factors for falls

The first step in fall prevention is to identify the

risk or precipitating factors for falls. Age by itself

is an important risk factor, but not the only one.

Falls in the elderly are often due to the interaction

of multiple risk factors. One practical way to help

clinicians identify risk or precipitating factors is to

use a mnemonic. One such mnemonic is shown in

the Table.8

Table. Mnemonic (A E I O U, A B B C C C) of risk or precipitating factors for falls (A is shared between vowels and ABC)8

Fall assessment

As falls are usually under-reported, a proactive

approach is to ask “Have you had a fall in the past

6 months?” at every encounter with an elderly

patient. Initial medical assessment involves a

focused history-taking, detailing the circumstances

of fall, precipitating factors, and consequences. A

witness can be helpful to identify unrecognised

syncope. Other relevant history includes living

environment, social support, past medical illnesses,

medication, history of falls or near falls, and mobility

and functional status. Comprehensive geriatric

assessment should follow documentation of history.9

Testing of gait, balance, and lower limb and joint

function, alongside cardiovascular and neurological

examination should be performed where relevant.

Postural blood pressure, vision, feet, and footwear

should also be checked. Measurement of postural

blood pressure requires a wait of at least 3 minutes

between sitting and standing (or lying and sitting),

and is often omitted or not done properly. Simple

bedside investigations such as electrocardiography

should be performed as arrhythmia may be the cause

of falls due to syncope. Further investigations should

be guided by the history and examination.

One simple screening test for mobility is the

timed up-and-go test.10 The patient is timed while

rising from a 46-cm high armchair, walking 3

metres, turning around, and returning to sit in the

chair (total 6 metres). The assessment should be

repeated with a walking aid if the patient is found

to be unsteady. Patients who require more than 20

seconds to complete the task are at risk of fall. It is

prudent to refer ‘fallers’ with multiple risk factors

to geriatricians for professional assessment and

management. Risk factors, once identified, should

then be managed with inter-disciplinary intervention

to reduce the risks as soon as possible. For example,

if impaired vision due to cataract is identified, an

expedited eye consultation and cataract treatment is

desirable to reduce the chance of recurrent falls.

Practical evidence-based strategies in fall prevention

Exercise

Multi-component exercises, including strength,

endurance and balance training, either in a group

or home-based, have been shown to reduce both

rate and risk of falling.11 The exercises need to be

of sufficient intensity to improve muscle strength.

Balance retraining appears to be the more important

component of any exercise programme designed to

decrease falls.12 The balance training can either be

specific dynamic balance retraining exercises or a

component of a movement programme such as Tai

Chi.13 Exercises should be regular and sustainable,

and be a part of multifactorial intervention (MFI;

see below). One should be aware that prescribing

inappropriate exercise may increase falls in the

elderly.

Tai Chi

The anecdote of Tai Chi in fall prevention is

generally well known to the public. Similar to multi-component

exercises, Tai Chi reduces both the

rate of fall and falling risk according to a Cochrane

Review.11 Wolf et al14 also reported the benefit of 10-form Tai Chi in a randomised controlled trial

(RCT). Tai Chi is a combination of strength and

balance training, with a certain aerobic element.15

In Hong Kong, most people practise the full form

that should theoretically be at least effective, if not

better. This can be promoted as a territory-wide

health recommendation. Nonetheless, not all Tai

Chi programmes improve balance. One local RCT

revealed no difference in the number of falls between

a Tai Chi group and controls after 12 months.16

Environmental interventions

Home modifications can effectively reduce risk

of falls in the community,11 and include removal

of floor mats, painting the edge of steps, reducing

glare, installing handles, and improving lighting.

Occupational therapists can provide expert advice

in this area. For older people with fall risk who live

at home, especially those who are usually alone,

installation of a safety alarm is recommended so help

can be summoned should an accident occur.

Medication review

Polypharmacy is common among older people

who often have multiple co-morbidities, and is an

independent variable that has been linked to falls in

older people.17 Many drugs, psychotropic medications

and antihypertensive agents in particular, are related

to falls. The use of psychotropic medication should

be confined to patients who do not respond to non-pharmacological

intervention and the lowest dosage

should be prescribed. Periodic review of indications

and side-effects should be undertaken: gradual

withdrawal of psychotropic medication can reduce

rate of falls in community-dwelling elderly people.11

Nonetheless drug withdrawal is a complicated

intervention that should be implemented by an

experienced clinician after carefully weighing the

risks and benefits. A standardised and explicit

medicine review tool such as the Beers Criteria

for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in

Older Adults and STOPP (Screening Tool of Older

Person’s potentially inappropriate Prescriptions)

may be useful in reducing falls in older people but

the effectiveness of these approaches has not been

proven by RCTs.18 19 Although drug withdrawal

is beneficial, studies that include RCTs show that

many withdrawals (eg sleeping pills) are reversed

and patients resume previous therapy. Ongoing

monitoring is therefore essential.20

Foot and footwear

Foot and footwear problems are common but are

often ignored. Footwear influences balance and

risk of falls. High-heeled shoes have been shown

to increase falls in older people. Anti-slip shoe

devices effectively reduce outdoor falls in slippery

conditions.21 A systematic review recommends that

elderly individuals wear shoes with a low heel and

firm slip-resistant soles, both inside and outside the

home.22 Podiatrists, and prosthetics and orthotics

professionals can give valuable advice in this

respect. A recent RCT has shown that multifaceted

podiatry intervention with foot orthoses, footwear

advice, education, and foot and ankle exercises can

reduce the rate of falls in community-dwelling older

people.23

Vitamin D supplement

The benefit of vitamin D in falls/fractures extends

beyond improved bone health. Vitamin D can

strengthen muscle and hence reduce falls. Meta-analysis

has shown that supplemental vitamin D at

a dose of 700 IU to 1000 IU a day reduces the risk of

falling among older individuals by 19%.24 The current

opinion is that in community-dwelling elderly,

vitamin D supplementation reduces the rate of falls

or risk of falling in a subgroup of people with low

vitamin D levels but its benefit is absent in people

without deficiency.11 In the institutionalised elderly,

vitamin D supplementation appears to be more

effective in reducing falls and the recommendation

is to prescribe vitamin D with or without calcium

supplements to older people with low vitamin D

levels or those who are institutionalised.11 Despite

these recommendations, most studies have been

conducted in western countries that experience a

quite different duration and intensity of sunshine to

Hong Kong. Whether the benefit of vitamin D in fall

prevention applies equally to Hong Kong Chinese

population is not known. Most public hospital

laboratories in Hong Kong do not have the means

to investigate vitamin D levels and clinicians are

required to send blood samples to private laboratories

for vitamin D level assay at a cost. Thus in the public

health sector, mass screening of the elderly for

vitamin D deficiency prior to supplementation is

impractical. The pragmatic approach is to encourage

a healthy balanced diet that is rich in vitamin D. For

older people who are at risk of fall, especially those

in residential care home for the elderly (RCHE), a

dose of 800 IU of vitamin D3 per day with or without

calcium supplementation is recommended, provided

there is no contra-indication.11 The clinician should

also ask whether the older person is taking any over-the-counter vitamin D–containing drugs before

commencing supplementation, as excess vitamin D

may result in hypercalcaemia.

Correction of vision

Poor visual acuity caused by presbyopia, cataract,

macular degeneration or glaucoma, reduction in

depth perception and contrast sensitivity are risk

factors for falls.25 Maximising vision with cataract

surgery is effective in fall prevention. In a UK RCT

that compared fast-track (4 weeks) with routine-queue

(12 months) first eye cataract surgery, a

significant reduction in fall and fracture rate in 1

year was observed in the fast-track group.26 Another

RCT by the same team showed that fast-track

surgery (4 weeks) for the second eye in older people

also produced a tendency to fewer falls compared

with the routine queue (12 months) group.27 One

should beware, though, that correction of vision

may sometimes result in increased falls. One RCT

showed that vision assessment and intervention may

increase the risk of falls and fractures, possibly due

to poor adjustment to new spectacles.28 Multifocal

lenses may increase fall risk by reducing contrast

sensitivity and depth perception in the lower visual

field when mobilising.29 As such, older individuals

should wear single lens glasses, especially when

performing outdoor activities.

Management of cardiovascular risk factors

Cardiovascular investigations and interventions

are indicated for those with fall related to syncope

and orthostatic hypotension. Neurally mediated

syndromes (carotid sinus hypersensitivity,

vasovagal syndrome, orthostatic hypotension,

postprandial hypotension), arrhythmias (sick sinus

syndrome, severe heart block, tachyarrhythmia),

and structural cardiac disease (valvular stenosis,

hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy, atrial

myxoma, aortic dissection) are all risk factors for

falls because they cause either attacks of syncope or

transient hypotension (pre-syncope).30 Randomised

controlled trials in older patients have shown that

those with dual-chamber pacemaker implantation

for cardio-inhibitory carotid sinus hypersensitivity

had significantly fewer falls and fall-related

injuries.31 32 It is beyond the scope of this article to

describe in detail the investigation and management

of individual cardiovascular conditions. Referrals to

cardiology colleagues are recommended for certain

conditions such as arrhythmias when appropriate.

Other conditions such as postural hypotension can

usually be managed by a geriatrician.

Multifactorial intervention

A MFI programme is a set of interventions designed

to address multiple elements of fall risk.33 The

elements of MFI usually include multi-component

exercises, medical assessment and management

of falls, medication adjustment, vitamin D

supplementation if appropriate, environmental

modifications, and patient education. Since falls are

often multifactorial in nature, MFI (rather than a

singular approach) is more likely to be effective and

is therefore recommended. The intervention can take

the form of a general MFI or be an individualised

MFI with tailor-made interventions based on specific

individual needs.11 Most evidence to support MFI

efficacy is in community-dwelling older people. In a

community setting, general MFI can achieve a 24%

to 31% reduction in fall risk, while individualised

MFI may improve this figure to 27% to 41%.10 Multi-factorial

intervention may not be effective in fall

prevention in other settings, such as in the accident

and emergency department.34 A recent Malaysian

RCT has just been completed to determine whether

MFI is appropriate in an Asian country; the results

are pending.35

Fracture reduction

Fall-related fractures can be reduced by improving

bone strength. Thus assessment of bone health

should be performed in older people as part of the

comprehensive assessment. If indicated clinically,

bone mineral density assessment can be undertaken

in patients at risk of fragility fracture.36 In addition

to vitamin D and calcium supplementation, specific

pharmacological treatment should be considered.

The World Health Organization FRAX (Fracture

Risk Assessment Tool) score can be used to guide

treatment by calculating the 10-year osteoporotic

fracture rate.37 It is beyond the scope of this article to

describe in detail the management of bone fragility.

Another means of fracture protection is the

use of hip protectors.38 Most hip protector designs

consist of two mechanically proven hard plastic cups

or soft pads placed or sewn to each side of a panty.

Compliance with their use has been a problem in

most studies though, and rates varying from 31%

to 68% have been reported, reducing in particular

over time.39 One local study reported overall

compliance rates of 55% to 70% with an 82% relative

risk reduction of hip fracture.40 In Hong Kong,

the hot and humid weather makes wearing of hip

protectors uncomfortable for a prolonged period of

time. Nonetheless a small reduction in hip fracture

risk was reported in a systematic review when hip

protectors were used in a RCHE with risk ratio of

0.82 (confidence interval, 0.67-1.00).41 No evidence

of such benefit was observed in a community setting,

hence their use should probably be confined to the

RCHE setting.

Fall prevention in hospital and residential care home setting

Multifactorial intervention in hospital and the

RCHE has been shown in a systematic review to

reduce rate of falls.42 The effective components were

comprehensive assessment, staff education, assistive

devices, and reduction of medications. Older

patients or residents should be assessed individually

to develop individualised MFI treatment plans.

However, the use of screening tools for risk of fall

is more controversial in the institutional setting. In

Hong Kong, screening tools such as Morse Fall Scale

and STRATIFY are mandated in many hospital

wards, long-stay wards in particular, with the former

more commonly used.43 44 To date though, there is

no evidence to support their use in fall prevention

in an institutional setting. An experienced nurse’s

clinical judgement is just as effective.45 In addition,

a disadvantage of screening tools is that they predict

fall due to physiological factors, not incidental falls

(eg patient slipping or tripping) or unpredictable

physiological falls (eg seizures, syncope). Other

risk factors for falls such as “impaired judgement in

patients with cognitive impairment” may also not be

included in traditional screening tools.46

Health care providers in hospitals or RCHEs

may employ physical restraints to older patients

when they are at risk of falling or delirious although

evidence suggests these are ineffective, not to

mention undignified.47 Further, patients may fall

more frequently and sustain more serious injuries.

Restraints increase the risk of delirium in the

hospital setting and the consequent immobilisation

precipitates other problems such as pressure

sores, respiratory complications, and death via

strangulation and aspiration. Although some long-stay hospitals and institutions in Hong Kong have

implemented a restraint reduction programme,

they remain commonly used in some institutional

settings.48

Vitamin D can be considered for all older

people who live in RCHEs where the prevalence of

deficiency is high. Other strategies for fall prevention

that have been used in institutional settings are

a chair/bed alarm system, ultra-low beds, and

changing of the floor surface from vinyl to carpet.

Nevertheless the effectiveness of these methods has

not been proven through RCTs.49

Fall prevention in the cognitively impaired older people

Although falls are common among the elderly, there

is insufficient evidence to recommend MFI or single

intervention for cognitively impaired older people

in community, hospital, and RCHE settings. The

elderly with dementia have often been excluded from

large-scale studies of falls. During training for fall

prevention, older patients may be required to learn

exercise skills and remember instructions; impaired

memory can affect the success of fall prevention.

Another report concludes that intervention for fall

prevention among cognitively impaired older people

in RCHEs is ineffective.50 Nonetheless some studies

have reported positive effects. A local retrospective

study showed that older people with dementia can

still benefit from rehabilitation.51 One meta-analysis

showed that strategies to prevent falls and fractures in

hospitals and RCHEs were not affected by cognitive

impairment.52 Another study demonstrated that the

number of falls in psychogeriatric RCHE residents

could be reduced by a targeted MFI.53 More

studies are required to determine the optimum fall

prevention strategies for older people with dementia.

Conclusion

Evidence-based interventions include multi-component

group or home-based exercises, Tai Chi,

environmental modifications, medication review,

management of foot and footwear problems, vitamin

D supplementation, and addressing cardiovascular

problems. If possible, these are best implemented

in the form of MFI. Bone health enhancement for

RCHE and appropriate community patients and

prescription of hip protectors for RCHE patients

are also recommended. A MFI programme may

also be useful in the hospital and RCHE setting. Use

of physical restraints is not recommended for fall

prevention. More high-quality studies are required

to examine fall prevention for older people with

cognitive impairment. Modern technology for fall

prevention, such as movement alarms and sensor

technology, should also be further explored.

References

1. Willeboordse F, Hugtenburg JG, van Dijk L, et al. Opti-Med: the effectiveness of optimised clinical medication

reviews in older people with ‘geriatric giants’ in general

practice; study protocol of a cluster randomised controlled

trial. BMC Geriatr 2014;14:116. Crossref

2. Nevitt MC, Cummings SR, Hudes ES. Risk factors

for injurious falls: a prospective study. J Gerontol

1991;46:M164-70. Crossref

3. Chu LW, Chi I, Chiu AY. Falls and fall-related injuries in

community-dwelling elderly persons in Hong Kong: a study

on risk factors, functional decline, and health services

utilization after falls. Hong Kong Med J 2007;13(Suppl

1):S8-12.

4. Chu LW, Chi I, Chiu AY. Incidence and predictors of falls in

the Chinese elderly. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2005;34:60-72.

5. Luk JK, Chiu PK, Chu LW. Factors affecting

institutionalization in older Hong Kong Chinese patients

after recovery from acute medical problems. Arch Gerontol

Geriatr 2009;49:e110-4. Crossref

6. Chu LW, Chiu AY. Chi I. Falls and subsequent health

service utilization in community-dwelling Chinese older

adults. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2008;46:125-35. Crossref

7. Hill AM, Hoffmann T, Hill K, et al. Measuring falls events

in acute hospitals—a comparison of three reporting

methods to identify missing data in the hospital reporting

system. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58:1347-52. Crossref

8. Chan DK. Chan’s practical geriatrics. 2nd ed. Brookvale,

NSW: BA Printing & Publishing Services; 2009.

9. Luk JK, Or KH, Woo J. Using the comprehensive geriatric

assessment technique to assess elderly patients. Hong

Kong Med J 2000;6:93-8.

10. Podsiadlo D, Richardson S. The timed “Up & Go”: a test

of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am

Geriatr Soc 1991;39:142-8.

11. Gillespie LD, Robertson MC, Gillespie WJ, et al.

Interventions for preventing falls in older people

living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

2012;(9):CD007146.

12. El-Khoury F, Cassou B, Charles MA, Dargent-Molina

P. The effect of fall prevention exercise programmes on

fall induced injuries in community dwelling older adults:

systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised

controlled trials. BMJ 2013;347:f6234. Crossref

13. Gardner MM, Robertson MC, Campbell AJ. Exercise in

preventing falls and fall related injuries in older people: a

review of randomised controlled trials. Br J Sports Med

2000;34:7-17. Crossref

14. Wolf SL, Barnhart HX, Kutner NG, McNeely E, Coogler

C, Xu T; Atlanta FICSIT Group. Selected as the best paper

in the 1990s: Reducing frailty and falls in older persons: an

investigation of tai chi and computerized balance training.

J Am Geriatr Soc 2003;51:1794-803. Crossref

15. Hackney ME, Wolf SL. Impact of Tai Chi Chu’an practice

on balance and mobility in older adults: an integrative

review of 20 years of research. J Geriatr Phys Ther

2014;37:127-35. Crossref

16. Woo J, Hong A, Lau E, Lynn H. A randomised controlled

trial of Tai Chi and resistance exercise on bone health,

muscle strength and balance in community-living elderly

people. Age Ageing 2007;36:262-8. Crossref

17. Hammond T, Wilson A. Polypharmacy and falls in

the elderly: a literature review. Nurs Midwifery Stud

2013;2:171-5. Crossref

18. de Vries OJ, Peeters G, Elders P, et al. The elimination

half-life of benzodiazepines and fall risk: two prospective

observational studies. Age Ageing 2013;42:764-70. Crossref

19. Fick DM, Cooper JW, Wade WE, Waller JL, Maclean JR,

Beers MH. Updating the Beers criteria for potentially

inappropriate medication use in older adults: results

of a US consensus panel of experts. Arch Intern Med

2003;163:2716-24. Crossref

20. Campbell AJ, Robertson MC, Gardner MM, Norton

RN, Buchner DM. Psychotropic medication withdrawal

and a home-based exercise program to prevent falls: a

randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 1999;47:850-3.

21. McKiernan FE. A simple gait-stabilizing device reduces

outdoor falls and nonserious injurious falls in fall-prone

older people during the winter. J Am Geriatr Soc

2005;53:943-7. Crossref

22. Menant JC, Steele JR, Menz HB, Munro BJ, Lord SR.

Optimizing footwear for older people at risk of falls. J

Rehabil Res Dev 2008;45:1167-81. Crossref

23. Spink MJ, Menz HB, Fotoohabadi MR, et al. Effectiveness

of a multifaceted podiatry intervention to prevent falls in

community dwelling older people with disabling foot pain:

randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2011;342:d3411. Crossref

24. Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Dawson-Hughes B, Staehelin HB, et

al. Fall prevention with supplemental and active forms of

vitamin D: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials.

BMJ 2009;339:b3692. Crossref

25. Lord SR. Visual risk factors for falls in older people. Age

Ageing 2006;35 Suppl 2:ii42-ii45. Crossref

26. Harwood RH, Foss AJ, Osborn F, Gregson RM, Zaman A,

Masud T. Falls and health status in elderly women following

first eye cataract surgery: a randomised controlled trial. Br

J Ophthalmol 2005;89:53-9. Crossref

27. Foss AJ, Harwood RH, Osborn F, Gregson RM, Zaman A,

Masud T. Falls and health status in elderly women following

second eye cataract surgery: a randomised controlled trial.

Age Ageing 2006;35:66-71. Crossref

28. Cumming RG, Ivers R, Clemson L, et al. Improving vision

to prevent falls in frail older people: a randomized trial. J

Am Geriatr Soc 2007;55:175-81. Crossref

29. Lord SR, Dayhew J, Howland A. Multifocal glasses impair

edge-contrast sensitivity and depth perception and

increase the risk of falls in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc

2002;50:1760-6. Crossref

30. Brian JC, Potter JF. Cardiovascular causes of falls. Age and

Ageing 2001;30 Suppl 4:19-24. Crossref

31. Ryan DJ, Nick S, Colette SM, Roseanne K. Carotid sinus

syndrome, should we pace? A multicentre, randomised

control trial (Safepace 2). Heart 2010;96:347-51. Crossref

32. Kenny RA, Richardson DA, Steen N, Bexton RS, Shaw FE,

Bond J. Carotid sinus syndrome: a modifiable risk factor

for nonaccidental falls in older adults (SAFE PACE). J Am

Coll Cardiol 2001;38:1491-6. Crossref

33. Day LM. Fall prevention programs for community-dwelling

older people should primarily target a multifactorial

intervention rather than exercise as a single intervention.

J Am Geriatr Soc 2013;61:284-5; discussion 285-6. Crossref

34. Russell MA, Hill KD, Day LM, et al. A randomized

controlled trial of a multifactorial falls prevention

intervention for older fallers presenting to emergency

departments. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58:2265-74. Crossref

35. Tan PJ, Khoo EM, Chinna K, Hill KD, Poi PJ, Tan MP. An

individually-tailored multifactorial intervention program

for older fallers in a middle-income developing country:

Malaysian Falls Assessment and Intervention Trial

(MyFAIT). BMC Geriatr 2014;14:78. Crossref

36. Osteoporosis Society of Hong Kong (OSHK). 2013 OSHK

Guideline for Clinical Management of Postmenopausal

Osteoporosis in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J

2013;19(Supplement 2):S1-40.

37. Michieli R, Carraro AM. General Practitioner and FRAX(®)

(computer-based algorithm). Clin Cases Miner Bone

Metab 2014;11:120-2.

38. Gillespie WJ, Gillespie LD, Parker MJ. Hip protectors

for preventing hip fractures in older people. Cochrane

Database Syst Rev 2010;(10):CD001255.

39. Sawka AM, Boulos P, Beattie K, et al. Do hip protectors

decrease the risk of hip fracture in institutional and

community-dwelling elderly? A systematic review and

meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Osteoporos

Int 2005;16:1461-74. Crossref

40. Woo J, Sum C, Yiu HH, Ip K, Chung L, Ho L. Efficacy of a

specially designed hip protector for hip fracture prevention

and compliance with use in elderly Hong Kong Chinese.

Clin Rehabil 2003;17:203-5. Crossref

41. Santesso N, Carrasco-Labra A, Brignardello-Petersen R.

Hip protectors for preventing hip fractures in older people.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;(3):CD001255.

42. Cameron ID, Gillespie LD, Robertson MC, et al.

Interventions for preventing falls in older people in care

facilities and hospitals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

2012;(12):CD005465.

43. Morse JM, Morse R, Tylko S. Development of a scale to

identify the fall-prone patient. Can J Aging 1989;8:366-77. Crossref

44. Oliver D, Britton M, Seed P, Martin FC, Hopper AH.

Development and evaluation of evidence based risk

assessment tool (STRATIFY) to predict which elderly

inpatients will fall: case-control and cohort studies. BMJ

1997;315:1049-53. Crossref

45. Meyer G, Köpke S, Haastert B, Mülhauser I. Comparison

of a fall risk assessment tool with nurses’ judgement

alone: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing

2009;38:417-23. Crossref

46. Chan DK, Diu E, Loh F. Pilot study into impaired

judgement, self-toileting behaviour in fallers and nonfallers.

Eur J Ageing 2013;10:257-60. Crossref

47. Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare.

Preventing falls and harm from falls in older people. Best

practice guidelines for Australian hospitals and residential

aged care facilities. In: Canberra (Australia): Australian

Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare; 2009.

48. Kwok T, Bai X, Chui MY, et al. Effect of physical restraint

reduction on older patients’ hospital length of stay. J Am

Med Dir Assoc 2012;13:645-50. Crossref

49. Becker C, Rapp K. Fall prevention in nursing homes. Clin

Geriatr Med 2010;26:693-704. Crossref

50. Jensen LE, Padilla R. Effectiveness of interventions to

prevent falls in people with Alzheimer’s disease and related

dementias. Am J Occup Ther 2011;65:532-40. Crossref

51. Luk JK, Chiu PK, Chu LW. Rehabilitation of older Chinese

patients with different cognitive functions: how do they

differ in outcome? Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2008;89:1714-9. Crossref

52. Oliver D, Connelly JB, Victor CR, et al. Strategies to

prevent falls and fractures in hospitals and care homes

and effect of cognitive impairment: systematic review and

meta-analyses. BMJ 2007;334:82. Crossref

53. Neyens JC, Dijcks BP, Twisk J, et al. A multifactorial

intervention for the prevention of falls in psychogeriatric

nursing home patients, a randomised controlled trial

(RCT). Age Ageing 2009;38:194-9. Crossref