Hong Kong Med J 2015 Feb;21(1):85–7 | Epub 5 Dec 2014

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj144455

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

COMMENTARY

Has dengue found its home in Hong Kong?

CM Poon, BSSC1; SS Lee, MD, FHKAM (Medicine)2

1 Jockey Club School of Public Health and Primary Care, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

2 Stanley Ho Centre for Emerging Infectious Diseases, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Prof SS Lee (sslee@cuhk.edu.hk)

In Hong Kong, the recent report of locally acquired

dengue cases has raised concern about the

introduction of dengue virus in our community.

Within just over a month, three people with no

travel history during the incubation period have

been confirmed to have dengue virus infection. As

there was no epidemiological link between the third

patient and the previous two, multiple sources of

infection and the possibility of ongoing transmission

within Hong Kong are suggested. Temporally, the

emergence of these three cases follows closely the

large outbreak in Guangdong, which affected more

than 40 000 people. Given the scale of the outbreak,

the Department of Health of Guangdong Province

has released updates on the dengue situation on a

daily basis from 22 September 2014 to the end of

October 2014.1 Dengue activity peaked between 29

September and 13 October, with almost 10 000 cases

reported each week. More than 80% of the cases

were notified in Guangzhou.

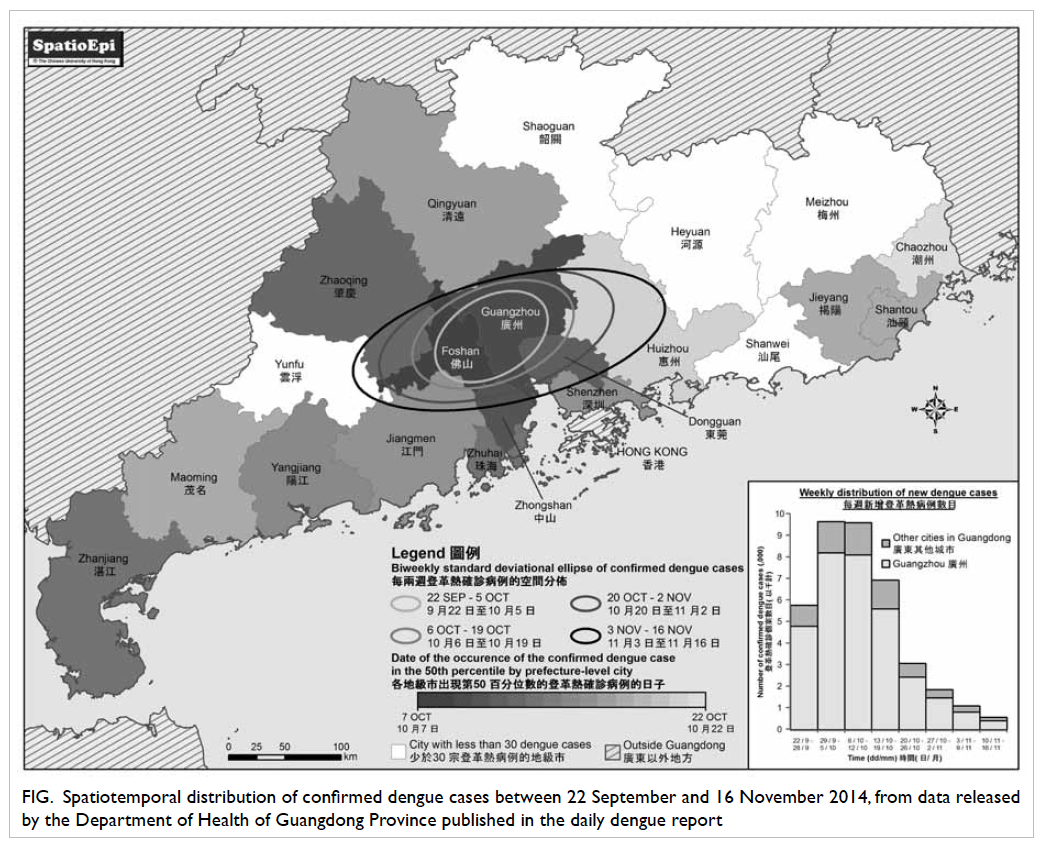

Epidemiological information for the

Guangdong outbreak can be accessed on the Internet,

which allows us to map the dengue distribution by

city and the changes over time with the Geographic

Information System. The scale of the outbreak has

evidently expanded geographically in Guangdong

since its onset, as shown by the biweekly standard

deviational ellipses, each of which would have

covered approximately 68% of the dengue cases in

the respective fortnight (Fig). Guangzhou remained

the spatial centre of the outbreak during these weeks.

A similar temporal distribution of dengue cases was

observed in other cities in the Pearl River Delta

(PRD), while places further away from the delta were

subsequently affected at a diminished level, like a

ripple effect. Researchers from Mainland China

had previously suggested the PRD and Chao Shan

Area as the two main hubs in Guangdong where

indigenous dengue cases have clustered since the

turn of the century.2 It appears, therefore, that this

latest outbreak is the result of extensive transmission

of dengue virus from the PRD hub.

Figure. Spatiotemporal distribution of confirmed dengue cases between 22 September and 16 November 2014, from data released by the Department of Health of Guangdong Province published in the daily dengue report

Even before the change in sovereignty, the PRD

was gradually transformed into a Chinese region

where many inhabitants move within and between

cities every day. With the rising number of people

who live in the PRD, Hong Kong is no different to a

prefecture-level city of Guangdong. Currently, Hong

Kong’s population comprises an estimated 200 000

mobile residents, with the majority travelling

back and forth to Guangdong.3 Mainland China’s

transport system, with its increasing efficiency,

not only reduces the travel time between cities in

Guangdong, but also accelerates the propagation of

infections in the region. In the past decade, dengue

outbreaks have been reported in places as far apart

as Zhejiang and Henan,4 5 6 a scenario proving that

human mobility is crucial in predisposing to virus

spread. It is conceivable that the latest Guangdong

outbreak has led to concurrent maintenance of

multiple pools of actively infected people commuting

in the PRD who, in the presence of the Aedes

mosquitoes, have enabled the virus to find a new

home base. Beginning in August 2014, three local

dengue cases were reported in Macau,7 coinciding

with the reported onset of the Guangdong outbreak.

The Guangdong epidemic undoubtedly increases

the likelihood of exposure to dengue virus among

mobile residents, the magnitude of which varies

with the place, time, and duration of their stay, as

well as their commuting frequency. Geographically,

dengue virus transmission might be more likely to

occur in some districts in Hong Kong. This does

not necessarily imply a direct association with the

size of the vector population, but the heterogeneous

distribution of mobile residents in the territory.3

Theoretically, one useful way to guard Hong

Kong from importation of dengue virus is to track

the situation in neighbouring countries. However,

the uniqueness of the natural history of dengue virus

infection poses a challenge to accurately predicting

its epidemiological risk. Clinically, dengue fever is

typically a self-limiting condition with an incubation

period ranging between 3 and 14 days.8 Since most

people infected with dengue virus have no or mild

signs or symptoms, a significant proportion are never

diagnosed or reported.9 Consequently, estimation

from the size and distribution of actively infected

people can hardly reflect dengue epidemiology.

Serological testing of dengue antibody may infer

the proportional distribution of the population

with previous exposure to the virus, but is unable to

determine the actual size of the ‘infective’ population.

A study in 2007 to 2009 in Hong Kong gave a

prevalence of positive dengue immunoglobulin G

of 1.6%, a figure that cannot provide insight into

the current epidemiological status.10 Importantly,

clinical testing plays no direct role in public health

interventions. It is also almost impossible to

intercept asymptomatic travellers or those in latent

infection from entering Hong Kong. Introduction of

dengue virus into our neighbourhood is therefore

often silent and discovered after several waves of

transmissions.

Upon identification of a locally acquired

dengue case in Hong Kong, epidemiological

investigations and vector control measures have

been conducted immediately to prevent secondary

spread. Coincidentally, the three recently reported

local dengue patients either worked or lived in

the vicinity of a construction site, and breeding of

mosquito larvae was found during site inspection.11

This reminds us of the lesson from the outbreak

related to a construction site in Ma Wan in 2002,

affecting 16 workers and residents nearby.12 Whereas

the previous outbreak was limited to an island, the

residences and suspected infection sources of the

three recent local dengue patients were sporadically

distributed in several densely populated districts,

suggesting a higher risk for subsequent evolvement

of dengue endemicity. Prior to the Ma Wan outbreak,

a major dengue outbreak occurred in Macau in

the preceding year, with a total of 1418 reported

cases.13 Although the exact source of the Macau

outbreak could not be ascertained, it also occurred

at a time when infrastructure development was

gaining momentum. Dengue dissemination could

well be the outcome of a perfect match between

increasing human mobility and urban development.

Understandably vector surveillance is a key

component of current environmental measures.

Ovitraps have been strategically established in 44

locations in Hong Kong to monitor the extensiveness

of the distribution of Aedes mosquitoes.14 However,

the insufficient geographical coverage of ovitraps

limits their ability to detect the invasion of dengue

virus as Aedes albopictus has a short flight range of

no more than 200 metres.15 Thus, the eggs sampled

in the ovitraps can only represent the mosquitoes

in a confined geographic area. Nevertheless, the

importance of eliminating mosquito breeding sites

in our highly urbanised environment cannot be

overemphasised. This is, however, a real challenge,

even for dengue-endemic Singapore where the

hygiene standard is enviably high.16

Even without any new locally acquired

dengue cases in the coming months, the medical

profession should remain vigilant and advise on

effective prevention. The virus can hide in the eggs

of infected mosquitoes this winter and becomes

reactivated when the weather is favourable for

breeding again.17 The next round of local dengue

transmission could probably begin after the spring,

merging with the anticipated upsurge of indigenous

dengue infections in the PRD every late summer,2

which are our potential external sources of dengue

virus. In consideration of the incident local dengue

cases and our dengue endemic neighbours, there is

no doubt that dengue virus has found its home in

Hong Kong. It is just a matter of whether this is a

temporary home or a permanent base.

References

1. The Department of Health of Guangdong Province. Updates on

epidemics [in Chinese]. Available from: http://www.gdwst.gov.cn/a/yiqingxx/. Accessed 18 Nov 2014.

2. Li Z, Yin W, Clements A, et al. Spatiotemporal analysis of

indigenous and imported dengue fever cases in Guangdong

province, China. BMC Infect Dis 2012;12:132. CrossRef

3. Census and Statistics Department, Hong Kong. 2011

Population Census. Available from: http://www.census2011.gov.hk/en/index.html. Accessed 18 Nov 2014.

4. Xu G, Dong H, Shi N, et al. An outbreak of dengue virus

serotype 1 infection in Cixi, Ningbo, People’s Republic

of China, 2004, associated with a traveler from Thailand

and high density of Aedes albopictus. Am J Trop Med Hyg

2007;76:1182-8.

5. Wu JY, Lun ZR, James AA, Chen XG. Dengue fever in

mainland China. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2010;83:664-71. CrossRef

6. Huang XY, Ma HX, Wang HF, et al. Outbreak of dengue

fever in Central china, 2013. Biomed Environ Sci

2014;27:894-7.

7. Health Bureau, Macao. Infectious disease information.

Available from: http://www.ssm.gov.mo/portal/csr/ch/main.aspx. Accessed 27 Nov 2014.

8. Rudolph KE, Lessler J, Moloney RM, Kmush B, Cummings

DA. Incubation periods of mosquito-borne viral infections: a systematic review. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2014;90:882-91. CrossRef

9. Chastel C. Eventual role of asymptomatic cases of dengue

for the introduction and spread of dengue viruses in non-endemic

regions. Front Physiol 2012;3:70. CrossRef

10. Lo CL, Yip SP, Leung PH. Seroprevalence of dengue in the

general population of Hong Kong. Trop Med Int Health

2013;18:1097-102. CrossRef

11. Hong Kong SAR Government press release. Government

enhances anti-mosquito measures in prevention of dengue

fever. 21 November 2014. Available from: http://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/201411/11/P201411110853.htm. Accessed 27 Nov 2014.

12. Ma SK, Wong WC, Leung CW, et al. Review of vector-borne

diseases in Hong Kong. Travel Med Infect Dis

2011;9:95-105. CrossRef

13. Almeida AP, Baptista SS, Sousa CA, et al. Bioecology and

vectorial capacity of Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae)

in Macao, China, in relation to dengue virus transmission.

J Med Entomol 2005;42:419-28. CrossRef

14. Audit Commission, Hong Kong. Director of Audit’s Report

No. 63. Available from: http://www.aud.gov.hk/pdf_e/e63ch05.pdf. Accessed 24 Nov 2014.

15. Marini F, Caputo B, Pombi M, Tarsitani G, della Torre A.

Study of Aedes albopictus dispersal in Rome, Italy, using

sticky traps in mark-release-recapture experiments. Med

Vet Entomol 2010;24:361-8. CrossRef

16. Ooi EE, Goh KT, Gubler DJ. Dengue prevention and 35

years of vector control in Singapore. Emerg Infect Dis

2006;12:887-93. CrossRef

17. Lee HL, Rohani A. Transovarial transmission of dengue

virus in Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus in relation to

dengue outbreak in an urban area in Malaysia. Dengue

Bulletin 2005;29:106-11.

Find HKMJ in MEDLINE: