Hong Kong Med J 2015 Feb;21(1):52–60 | Epub 2 Jan 2015

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj144410

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

REVIEW ARTICLE

Allergy in Hong Kong: an unmet need in service provision and training

YT Chan, MB, BS, FHKAM (Pathology)1;

HK Ho, MB, BS, FHKAM (Paediatrics)2;

Christopher KW Lai, DM, FRCP3;

CS Lau, FRCP, FHKAM (Medicine)4;

YL Lau, MD, FHKAM (Paediatrics)2;

TH Lee, ScD, FRCP5;

TF Leung, MD, FRCPCH6;

Gary WK Wong, MD, FRCPC6;

YY Wu, MB, ChB, DABA&I3; The Hong Kong Allergy Alliance

1Division of Clinical Immunology, Department of Pathology and Clinical

Biochemistry, Queen Mary Hospital, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

2Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Queen Mary

Hospital, The University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

3Private practice, Hong Kong

4Division of Rheumatology and Clinical Immunology, Department of

Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

5Allergy Centre, Hong Kong Sanatorium & Hospital, Hong Kong

6Department of Paediatrics, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Prince

of Wales Hospital, Shatin, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr TH Lee (thlee@hksh.com)

Abstract

Many children in Hong Kong have allergic diseases

and epidemiological data support a rising trend.

Only a minority of children will grow out of their

allergic diseases, so the heavy clinical burden will

persist into adulthood. In an otherwise high-quality

health care landscape in Hong Kong, allergy services

and training are a seriously unmet need. There is one

allergy specialist for 1.5 million people, which is low

not only compared with international figures, but also

compared with most other specialties in Hong Kong.

The ratio of paediatric and adult allergists per person

is around 1:460 000 and 1:2.8 million, respectively,

so there is a severe lack of adult allergists, while the

paediatric allergists only spend a fraction of their

time working with allergy. There are no allergists

and no dedicated allergy services in adult medicine

in public hospitals. Laboratory support for allergy

and immunology is not comprehensive and there is

only one laboratory in the public sector supervised

by accredited immunologists. These findings clearly

have profound implications for the profession

and the community of Hong Kong and should be

remedied without delay. Key recommendations are

proposed that could help bridge the gaps, including

the creation of two new pilot allergy centres in a hub-and-spoke model in the public sector. This could

require recruitment of specialists from overseas to

develop the process if there are no accredited allergy

specialists in Hong Kong who could fulfil this role.

Introduction

There is a global epidemic of allergic diseases in

the developed world and Hong Kong has not been

spared. This review provides an overview of the

epidemiology of allergic diseases in Hong Kong

and matches it to the provision of local health care

services as well as training in allergy.

How common are allergic diseases in Hong Kong?

The International Study of Asthma and Allergies

in Childhood (ISAAC)1 2 3 4 5 6 and other local studies7 8 9 10 11

provide data on the prevalence and changing trends

for some allergic diseases in Hong Kong. The ISAAC

was a multi-country cross-sectional survey that

provided a global epidemiological map of eczema,

asthma, and rhinoconjunctivitis in 1995, 2000,

and 2003. Children aged 6 to 7 years and 13 to 14

years were studied. The ISAAC Phase Three was a

repetition of the ISAAC Phase One that aimed to

evaluate the possible trend of disease prevalence

after a period of 5 to 10 years.

In 2001, the prevalence of those who had ever

been diagnosed with asthma in 6- to 7-year-olds

was 7.9%. This reflected an increase of about 0.04%

compared with 1995. In 2002 the prevalence of

having asthma ever in 13- to 14-year-olds was 10.1%,

representing a decrease in prevalence of 0.15% per

year since 1995.

In 2001, the prevalence of lifetime eczema in

6- to 7-year-olds was 30.7% and current eczema was

4.6%. This reflected an increase in the current eczema

prevalence of 0.12% per year since 1995. In 13- to

14-year-olds, the prevalence of lifetime eczema was

13.4% and that of current eczema was 3.3%. This reflected

an increase of 0.08% per year since 1995.

In 2002, the rhinoconjunctivitis prevalence in

13- to 14-year-olds was 22.6% and showed a decrease

of 0.2% per year since 1995. Similar figure for 6- to

7-year-olds was 17.7% in 2001 and this represented

an increase of 0.7% per year since 1995.

The Asthma Insights and Reality in Asia-Pacific

Study was conducted twice in Asian countries,

including mainland China, Hong Kong, Korea,

Malaysia, The Philippines, Taiwan, and Vietnam,

to gain insight into asthma management.12 In the

first survey of more than 3000 adults and children,

more than 40% of asthmatic patients had at least one

hospitalisation or visit to the emergency department

for acute exacerbation. Inhaled corticosteroid use

was reported by only 13.6% of the respondents.

Another study performed 10 years after the first

survey showed that less than 5% of patients achieved

a level of complete asthma control, while more than

one third were in the uncontrolled asthma category.

Patients tended to overestimate their level of control

and tolerated a high degree of impairment of their

daily activities.12 13 14 Most participants younger than

16 years had inadequately controlled asthma (53.4%

‘uncontrolled’ and 44.0% ‘partly controlled’). The

demands for urgent health care services (51.7%) and

use of short-acting β-agonists (55.2%) were high.15

There are little epidemiological data on

asthma and allergy in Hong Kong adults. In a

review of data from local public hospitals in 2005,

asthma ranked fourth and fifth highest as a cause of

respiratory hospitalisations (5.7%) and respiratory

inpatient bed-days (2.6%), respectively.16 The overall

crude hospitalisation rate for asthma in 2005 was

76/100 000, and was high at both extremes of age. The

age-standardised mortality rate of asthma increased

between 1997 (1.33/100 000) and 1998 (1.82/100 000),

but decreased thereafter to 1.4/100 000 in 2005. The

overall annual change in asthma mortality was not

significantly different between 1997 and 2005. The

prevalence of current wheeze increased from 7.5%

in 1991/1992 to 12.1% in 2003/2004 among people

older than 70 years; the corresponding figures for

asthma were 5.1% and 5.8%.17

A number of studies have examined the

prevalence of food allergies and adverse food

reactions in a wide age range of Hong Kong

children.9 10 11 18 In 2009, parent-reported adverse

reactions in 2- to 7-year-olds was 8.1%. A study

involving children aged 7 to 10 years reported in

2010 that ‘probable’ food allergy in Hong Kong

was 2.8%.10 In 2012, the prevalence of food allergy in

children from birth to 14 years was 4.8%, of which

shellfish was by far the commonest food causing

allergic symptoms, alongside egg, milk, peanuts, and

fruits.10

Children with food allergies have 2 to 4 times

higher rates of co-morbid conditions, including

asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema. Strikingly

700/100 000 of the population (15.6% of children

with food allergies) aged 14 years or younger are

estimated to be at risk for anaphylaxis, which is high

relative to other countries. Almost 50% of cases are

estimated to be caused by foods, with drug allergy

also being a cause.11

Regarding other allergic diseases, Leung et

al19 reported glove-related symptoms in nearly

one third of 1472 employees in a teaching hospital

in Hong Kong. Most of these allergies could be

classified as glove dermatitis, whereas only 3.3% had

symptoms suggestive of latex allergy. About 7% of

133 participants had positive skin prick testing to

one or more of the five latex extracts.

How does Hong Kong compare

with the rest of the world in the

number of allergy specialists?

There are only four immunology and allergy

specialists (Medical Council Specialist Registration

S34) in Hong Kong. Two of these clinicians, both of

whom were trained abroad, are in private practice

and the other two are not involved in allergy practice.

There are no registered allergy specialists in adult

medicine in public hospitals.

There are six specialists in Paediatric

Immunology and Infectious Diseases (PIID; Medical

Council Specialist Registration S56) of whom two

work full time and four work part time, mainly in an

allergy/immunology practice in the Hospital Authority

(HA) hospitals/university sector. There is another

PIID specialist working in private practice. Most of

these clinicians only work part time on allergy.

Many patients with allergic diseases in Hong

Kong are treated by non-allergy specialists, such as

general practitioners, or specialists in dermatology,

respiratory medicine, ear nose and throat medicine,

and paediatrics. While these excellent clinicians

undoubtedly have experience in looking after

patients with allergies, it is unclear how many have

received formal training in managing complex

multi-system allergies or whether their continuous

professional development (CPD) activities include

allergy.

If one assumes that PIID specialists spend on

average 40% of their working week (5.5 days) on

allergy, irrespective of whether they are full or part

time (a generous estimate), then Hong Kong has 2

full-time equivalent (FTE) adult allergists and 2.8

FTE PIID specialists consulting for allergy. The

overall ratio is therefore estimated to be around one

allergist to 1.46 million population in Hong Kong,

which is near the bottom of the world league table

published by the World Allergy Organization

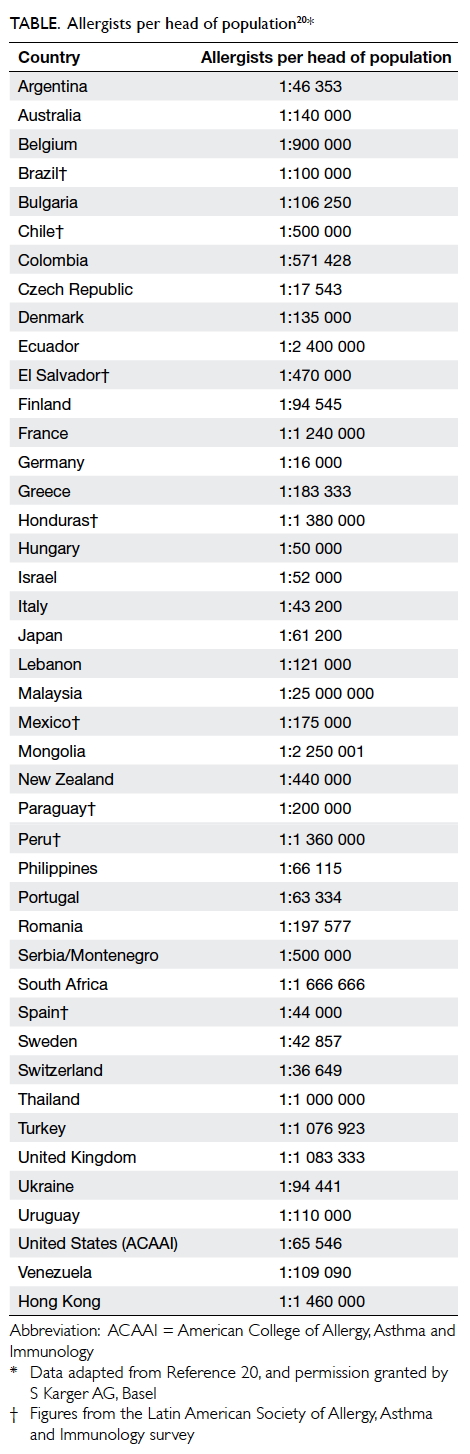

(Table20).

There is a stark contrast in Hong Kong

between the level of service provision for children

and that for adults. The ratio of paediatric and adult

allergists per head of population is around 1:460 000

(assuming there are about 1.3 million children in

Hong Kong who are younger than 18 years) and

1:2.8 million (assuming there are about 5.7 million

adults), respectively. There are no allergists for adult

patients in public hospitals. The very low numbers

of allergists (4.8 FTE) compares unfavourably with

other specialties in Hong Kong, for example, there

are 226 cardiologists, 164 gastroenterologists, 162

respiratory physicians, 190 otorhinolaryngologists,

and 92 dermatologists. These data, combined with

the average waiting times at public hospitals of 6

to 9 months for a new allergy appointment, clearly

indicate that the demands for allergy services are

unmet. The disease burden cannot be absorbed by

the private sector as there are also very few private

allergists.

Laboratory support is essential for the

good practice of allergy and immunology. There

are two Hong Kong Medical Council–registered

immunologists (S44) who have also received some

allergy training. One of them directs a public

laboratory service in immunology and allergy as well

as providing a limited service for drug allergy, while

the other is not involved with allergy. Their budget

does not allow a comprehensive menu of relevant

tests to support the specialty.

In countries where there are more allergists

per head of population than in Hong Kong, patients

still consult non-allergy specialists instead of an

allergist, even for a condition that often has an

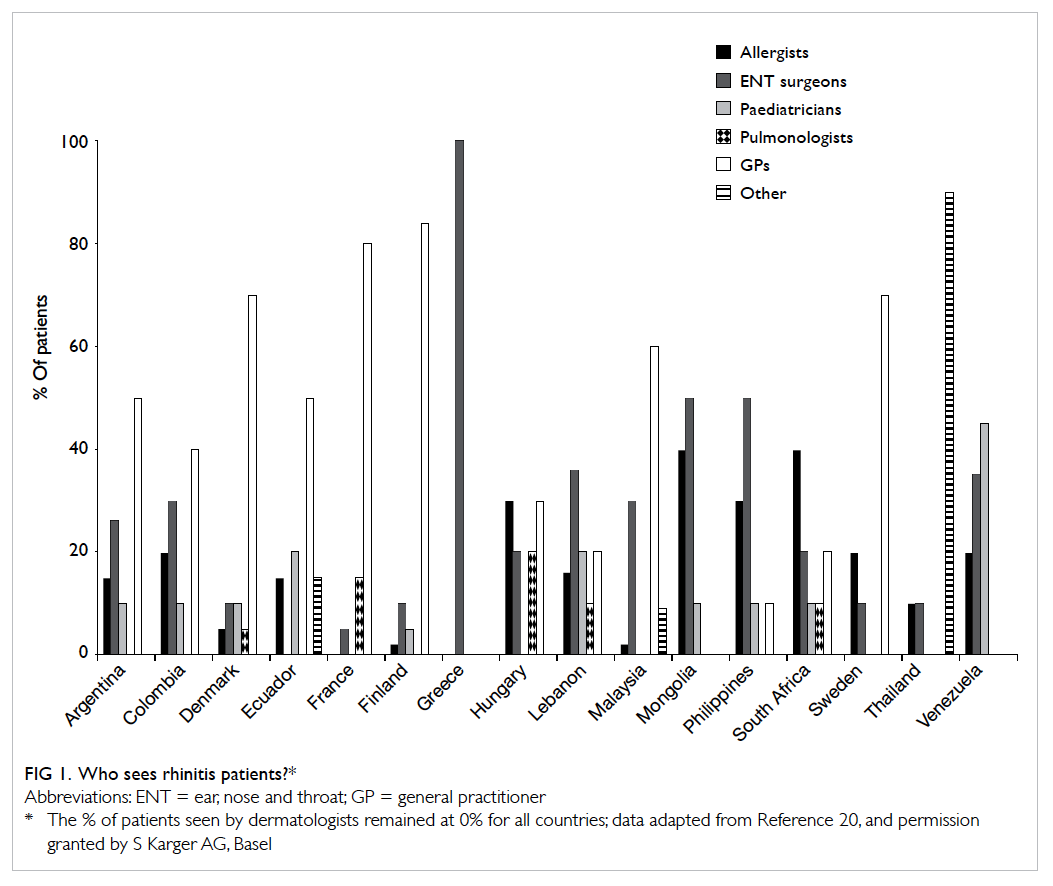

allergic cause such as rhinitis (Fig 120).This suggests

that there is a relative global lack of understanding

of what allergists can offer in health care. Clearly

much needs to be done in public and professional

education.

In the absence of allergists, patients may

suffer because they may find it hard to get state-of-the-art medicine and diagnostics. Pharmaceutical

companies are less likely to register their products

in a country where the drugs will be prescribed only

rarely. Furthermore, there is a high probability that

unproven diagnostic procedures and therapies could

be introduced if mainstream medicine is unavailable,

or conventional tests are used inappropriately.21

Finally, with a lack of allergy specialists, it becomes

difficult to train future generation of clinicians,

researchers, and teachers in allergy.

What is the provision of allergy services in public hospitals in Hong Kong?

Current situation for children

There are 12 acute paediatric units admitting children

and adolescents for various acute exacerbations of

diseases, including systemic allergic reactions and

acute asthmatic attacks. The level of acute care is

comprehensive and includes intensive care unit

support when indicated. Data from the HA suggest

that one in 10 patients with anaphylaxis attending

acute emergency departments has been admitted to

a paediatric intensive care unit.22

Ambulatory and out-patient follow-ups,

however, are sometimes fragmented, especially for

the prevention of anaphylaxis and investigation

to identify allergens. Adrenaline auto-injector (eg

EpiPen [Dey LP, Napa, California, US]) availability

is very limited, although much improved recently,

probably as the result of an audit report identifying

the unmet need.22

Only four hospitals have designated allergy

clinics to investigate food and drug allergy (Queen

Mary Hospital [QMH], Prince of Wales Hospital

[PWH], Princess Margaret Hospital [PMH],

and Queen Elizabeth Hospital [QEH]). Some

paediatricians with gastro-intestinal training look

after patients with non-immunoglobulin E (IgE)–mediated food allergy with predominant gastro-intestinal symptoms.

Most of the paediatric units in Hong Kong have

asthma clinics that are run by paediatricians with

respiratory training. Care of patients with allergic

rhinoconjunctivitis is largely provided by general

paediatricians in conjunction with other organ

specialists such as ear, nose and throat surgeons

and ophthalmologists; there are long waiting times,

ranging from 6 to 12 months.

Five hospitals have dermatology clinics (QMH,

PWH, United Christian Hospital, Caritas Medical

Centre, and Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern

Hospital) run by paediatricians with dermatology

training, but also treating some patients with

allergies.

Currently, there is one single immunology/allergy public laboratory service in QMH that

provides limited numbers of specific IgE, human

leukocyte antigen, and tryptase tests. Clinical

investigational laboratories for in-vivo allergen skin

tests and challenge protocols are run by specialists

in PIID or paediatrics. Food and drug challenges

are provided at QMH and PWH on a regular basis,

but may be occasionally provided by other hospitals

such as QEH, PMH, and Kwong Wah Hospital. The

waiting time is generally about 6 months. There are

no commonly accepted local challenge protocols, so

those used by internationally recognised paediatric

allergy centres are followed.

Currently, the four PIID centres have two FTE

staff plus four part-time staff who work mainly on

food and drug allergies. The trained dietician and

nurses work only on a part-time basis. There is also

one private PIID specialist.

Clinical guidelines

Local anaphylaxis guidelines have been drafted and

are pending approval and implementation. The Hong

Kong College of Paediatricians has issued guidelines

to improve care for atopic dermatitis. Different

hospitals may have different in-house guidelines for

asthma or they may be adopted from international

guidelines.

Allergen immunotherapy

Allergen immunotherapy is very limited in public

service. The reasons are multifactorial and include

affordability, availability, and accessibility.

Resources

Lack of central funding may seem to be a hindrance

to provision of allergy services, but the real problem

is the shortage of skilled staff. Many trained nurses

experienced in skin testing and allergy education

have left their jobs or have been redeployed to other

areas. To cater for the current service demands and

to achieve reasonable waiting times, more staff need

to be trained urgently, for instance, a resident trainee,

advanced practice nurses, and even clerical support.

Current situation for adults

There is currently no formal allergy clinical service

provided in the public sector for adults. Clinicians,

including a few dermatologists, respiratory

physicians and otolaryngologists, who have an

interest in allergy provide an ad-hoc service to

patients with various allergic disorders. Limited

skin prick tests are provided. There are, however, no

specialty nurses or technicians specially trained in

this area.

In 2013, the Division of Rheumatology and

Clinical Immunology, together with the Division

of Clinical Immunology (Pathology) set up a Drug

Allergy Clinic at QMH to provide consultations

for Hong Kong West Cluster patients. Because

of resource restrictions, these consultations are

limited to the diagnosis and confirmation of general

anaesthetic and antibiotic allergies.

Hong Kong has produced only one locally

trained immunologist who is an HIV (human

immunodeficiency virus) specialist currently

working in the Department of Health. There have

been no trainees in allergy and immunology since

1998.

Drug allergies

Data retrieved on 30 June 2013 from an analysis of HA data (personal communication) indicate that almost 400 000 patients have drug allergy, with

44 018 having three or more drug allergies. Almost

5000 patients (mainly adults) have three or more

antibiotic allergies. This is a huge potential clinical

workload that impacts on many other specialties,

and is a growing area of allergic disease that needs to

be addressed urgently.

Laboratory support services for allergy/immunology

Only one laboratory service for allergy/immunology in Hong Kong is directed by accredited

immunologists in the public sector (at QMH). The

service cannot offer a complete portfolio of tests

because of budgetary constraints.

Training

Paediatric Immunology and Infectious Diseases

The first Fellowships of the subspecialty of PIID were

conferred in 2012 (Medical Council Registration

S56). Among the first 12 Fellows, five work

principally in the field of immunology and allergy.

Paediatric units of four regional hospitals (QMH/The University of Hong Kong [HKU], PWH/The

Chinese University of Hong Kong [CUHK], PMH,

and QEH) are accredited to be the training centres

and they have formed a training network. Allergy is

an integral part of the PIID programme.

Higher training in allergy in adult medicine

Allergy and hypersensitivity is one of the five areas

of knowledge requirement for the training in allergy

and immunology under the Hong Kong College of

Physicians (HKCP). The other four areas include

autoimmune and immune complex diseases, primary

and secondary immunodeficiency, transplantation,

and lymphoproliferative diseases. Training in adult

allergy is hampered by the lack of trainers and the

lack of an allergy clinical service in the public sector.

Immunology

Training of immunology is under the Hong Kong

College of Pathologists (HKCPath). The goal of

training is to produce specialist immunologists who

are able to direct a laboratory service in clinical

immunology and tissue typing, to advise clinicians

on the management of immunological disorders,

including allergy, autoimmunity, immunodeficiency,

and malignancy of the immune system. At present

such training is only available at QMH where there

are two immunologists.

Recommendations

With the introduction of potent targeted biologics,

greater understanding of the genetics and

epigenetics determining allergic disease expression,

improved strategies and vaccines for allergen-specific

desensitisation, novel approaches to allergy

prevention, and the advent of an era of stratified

medicine, the need for more allergists, allergy

services, research, and trainees in the specialty have

never been more urgently required. In an otherwise

high-quality health care landscape in Hong Kong,

allergy services and training are a seriously unmet

need. The deficiencies should be remedied without

delay for the benefit of the patient community.

The recommendations described below are

adapted from a recent authoritative report about

allergy23 and should also be seen in the context of

the declaration of the World Allergy Organization in

2013.24

Model and location

(1) We recommend that urgent advice is sought

from the major stakeholders on how one might

remedy the unmet need for allergy services

and training in Hong Kong.

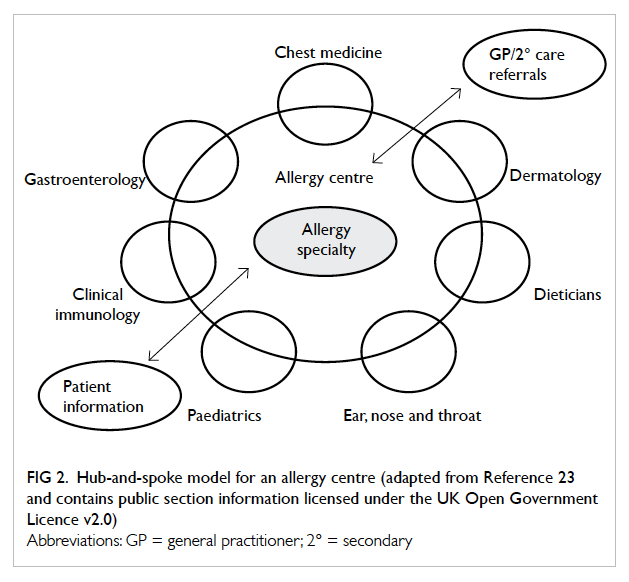

(2) We recommend that the best model for allergy

service delivery is a ‘hub-and-spoke’ model

(Fig 223). The ‘hub’ would act as a central point

of expertise with outreach clinical services,

education, and training provided to doctors,

nurses, and allied health care professionals in

primary and secondary care (the ‘spokes’). In

this way, knowledge regarding the diagnosis

and management of allergic conditions could

be disseminated throughout the region. The

hub and spokes in its entirety forms the ‘allergy

centre’. The hub should lead and coordinate the

activities of the entire centre.

(3) Each hub should have an allergy service

both for adults and for children to share in

knowledge transfer and resources. In addition

to hubs, a network of satellite allergy services

could be established at different hospitals (for

instance by changing the emphasis of one or

two existing clinics a week designated for

respiratory medicine, otorhinolaryngology,

and/or dermatology to become allergy clinics),

which can then link to one of the allergy hubs

for academic, clinical, and educational support.

This solution might not incur substantially

more resources, as the complex multi-system

allergy cases could be transferred from the

other clinics and managed in a new dedicated

allergy service.

(4) We recommend that paediatric and adult

services in an allergy centre should each be

led by an allergy specialist and each should

be supported by at least one other clinical

colleague (another allergy specialist or an organ

specialist with a special interest in allergy),

at least one trainee, specialist dietician and

nursing support, and a technician for routine

allergy testing, counselling, and education.

(5) The hub forming the allergy centre will be

collaborating, not competing, with single organ

specialists or with general paediatricians,

internists, and general practitioners. It is

envisaged that the tertiary allergy centres

would work together with other colleagues to

provide joint, integrated, and holistic care for

the most complex allergy cases, which are often

characterised by multi-system involvement. To

facilitate this interaction, it is recommended

that clear criteria are defined for the types

of patients that could be referred to tertiary

specialist allergy centres.

Figure 2. Hub-and-spoke model for an allergy centre (adapted from Reference 23 and contains public section information licensed under the UK Open Government Licence v2.0)

Adult allergy

(1) We recommend that two pilot allergy centres

are created by recruiting allergy specialists

(from overseas if necessary) to start the

services and to oversee a training programme.

(2) We recommend that each of the new

appointees is a joint appointment between the

HA and a university. Each appointee should be

supported by three trainees, a specialist nurse,

and a dietician.

(3) We recommend that the two pilot allergy

centres should be located at QMH/HKU and

PWH/CUHK (hubs), so that Hong Kong, Kowloon,

and the New Territories are covered. Two

pilot centres are required because of the heavy

burden of allergic disease and the capacity of a

solitary centre in Hong Kong would very soon

become overextended. Both QMH and PWH

have a long distinguished history of looking

after children with allergic and immunological

diseases, but both lack a dedicated allergist

in adult medicine. Creation of an allergy

centre that integrates existing strengths in

paediatric clinical/academic/education in

allergy with a new adult clinical/academic/education allergy service would be a major

catalyst to bridging the obvious gaps in service

and academic provision. Formal designation

of both hospitals as pilot allergy centres

could also provide formal encouragement to

hospital and university management for some

internal realignment of resources. Finally

creating these innovative allergy centres could

provide significant opportunities to attract

private funding from benefactors to grow the

discipline subsequently.

(4) We recommend that metrics for success of

each pilot centre be predefined and progress in

the first 5 years be assessed against those goals.

If the pilot is successful, then the model should

be continued and could even be extended to

other suitable clinical/academic centres.

(5) We recommend that the HKCP training

curriculum for immunology and allergy is

updated as soon as possible. In addition, we

suggest that the HKCP and HKCPath consider

creating an intercollegiate training programme

in immunology and allergy to produce clinical

immunologists who will direct allergy/immunology laboratories and consult for

allergic patients. This can be extended to

other colleges and cross-college training is

encouraged by the Hong Kong Academy of

Medicine. In due course, a core curriculum in

allergy could be shared by all interested colleges

in addition to a college-specific curriculum.

This model is already being explored for subspecialty

training in genetics and genomics

among some academy colleges.

(6) We recommend the training of allergy as a main

subject to be included in the college training

guidelines in allergy and immunology and four

allergy and immunology trainees majoring in

allergy are recruited every 4 years.

Paediatric allergy

(1) It is envisaged to develop an immunology and

allergy centre at the Hong Kong Children’s

Hospital (HKCH) for management of complex

allergy cases from 2018 onwards (a hub). A

team of core medical and nursing staff will be

based at HKCH, but will also run an outreach

programme by linking up with other network

hospitals.

(2) When the immunology and allergy centre at

the HKCH is operational, there will need to be

some reorganisation with parts of the top-tier

paediatric allergy services in the ‘hub’ hospitals

being moved to the HKCH (which will then

become the new hub), leaving satellite services

in the previous ‘hub’ hospitals (the spokes) in

situ.

(3) To facilitate a smooth transition to the HKCH,

we recommend at least four to five FTE PIID

specialists majoring in allergy/immunology

to be appointed to run the top-tier service at

the HKCH, to provide training and conduct

local relevant audit/research (hub). A further

12 PIID specialists will be required to provide

step-down and secondary services in both the

training (PMH, PWH, QEH, QMH) and non-training

(other HA paediatric units) posts for

the specialty and general paediatrics (spokes).

(4) We recommend that common protocols,

guidelines, care pathway, and a referral

network, especially for complex cases, should

be agreed and formally created.

(5) We recommend that four PIID trainees are

recruited every 3 years, of which at least

two resident specialists majoring in allergy/immunology should be trained. This will

maintain a sustainable public workforce for

specialty development and cover for normal

turnover. It should then be possible to produce

12 PIID specialists in three cycles (around

9 years), of whom 50% will have majored in

allergy/immunology with the rest majoring in

infectious diseases. Therefore, the estimated

total required workforce for PIID in the public

sector for the hub-and-spoke model could be

18 to 20 with eight in the hub (four to five in

allergy and immunology and two to three in

infectious diseases) and about 12 in the spokes

working in both the specialty and general

paediatrics.

(6) We recommend that allergy is added to the

title of the PIID training programme so it will

become a PIAID (paediatric immunology allergy and

infectious diseases) programme and

the paediatric discipline should also be so

named.

Drug allergy

Drug allergy is common and constitutes a major

clinical problem, which needs to be managed by

allergy specialists. We recommend resources to

be made available to establish two separate supraregional

drug allergy services at QMH and PWH (as

they already have a limited service) to cover Hong

Kong Island and Kowloon/New Territories. This

could be part of the new pilot centres.

Laboratory support

We recommend that two supraregional

laboratories for Hong Kong should be created with

a focus on drug and food allergy that are directed by

accredited immunologists. The laboratories should be

adequately funded so that they have sufficient manpower,

equipment, and budget for reagents to widen

the scope of routine laboratory services to include

tests for specific IgE to a wide spectrum of whole allergen

extracts and to allergen components, basophil

activation tests, and lymphocyte function tests. This

can be incorporated into existing laboratory support

at QMH and PWH with only a relatively modest

increase in resources. These laboratories could then

support the new pilot centres.

Education

We recommend that collaboration is established

between the Hong Kong Institute of Allergy (as

the professional platform) and Hong Kong Allergy

Association (as the allergy charity) to create an agenda

for professional CPD (such as regular workshops)

as well as engaging and educating the public about

allergy. These organisations are strongly encouraged

to involve other professional societies and charities

as appropriate when designing their strategies.

Schools

(1) We recommend that the appropriate

Government department should audit the

level of allergy training staff in schools receive,

and consider taking urgent remedial action to

improve this training where required.

(2) We recommend that the Government should

review the desirability of schools holding one

or two generic auto-injectors.

Air quality

Solving the urban air pollution problem is a huge

challenge. Bold, realistic, and moral leadership by

national leaders is required to address this increasingly

important public health issue. We recommend

that it is essential to develop effective strategies

to reduce pollution, to engage the public, and to

monitor whether the strategies result in a significant

improvement in the prevalence of pollution-related

diseases in Hong Kong and mainland China.

Conclusions

Epidemiological data support a rising trend in

many allergic diseases. The provision of services

and training for specialists in allergy is mismatched

with disease burden and there is a large unmet

need that should be remedied without delay. Key

recommendations are proposed that could help

bridge the gaps, including the creation of two

pilot allergy centres in a hub-and-spoke model in

the public sector. This could require recruitment

of specialists from overseas to start the process in

the likely event that there are no accredited allergy

specialists in Hong Kong who could fulfil this role in

the short term.

Declarations of interest

Drs CKW Lai, CS Lau, YY Wu, and Prof TF Leung

are consultants or serve on advisory boards and/or

receive travel expenses and lecture fees to attend

international meetings from various pharmaceutical

companies including GlaxoSmithKline, AstraZeneca, Takeda, Mundipharma, Boehringer, ALK-Abello, AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celltrion, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi, and Union Chimique Belge. Dr TH Lee is President of the Hong Kong Institute of Allergy and Honorary Clinical Professor,

The University of Hong Kong. Dr Marco Ho is

Chairman of the Hong Kong Allergy Association.

The Hong Kong Allergy Alliance is a group of individuals

with an interest in allergy drawn from academia, HA

hospitals, private practitioners, representatives from

the HA, Hong Kong Institute of Allergy, Hong Kong

Thoracic Society, Hong Kong Allergy Association,

patients, and drug company representatives from

ALK.

References

1. Worldwide variation in prevalence of symptoms of asthma,

allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and atopic eczema: ISAAC. The

International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood

(ISAAC) Steering Committee. Lancet 1998;351:1225-32. CrossRef

2. Worldwide variations in the prevalence of asthma

symptoms: the International Study of Asthma and Allergies

in Childhood (ISAAC). Eur Respir J 1998;12:315-35. CrossRef

3. Asher MI, Montefort S, Björkstén B, et al. Worldwide time trends in the prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic

rhinoconjunctivitis and eczema in childhood: ISAAC

Phases One and Three repeat multicountry cross-sectional

surveys. Lancet 2006;368:733-43. CrossRef

4. Pearce N, Aït-Khaled N, Beasley R, et al. Worldwide trends

in the prevalence of asthma symptoms: phase III of the

International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood

(ISAAC). Thorax 2007;62:758-66. CrossRef

5. Williams H, Stewart A, von Mutius E, Cookson W,

Anderson HR; International Study of Asthma and Allergies

in Childhood (ISAAC) Phase One and Three Study Groups.

Is eczema really on the increase worldwide? J Allergy Clin

Immunol 2008;121:947-54.e15.

6. Lai CK, Beasley R, Crane J, Foliaki S, Shah J, Weiland S;

International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood

Phase Three Study Group. Global variation in the

prevalence and severity of asthma symptoms: phase three

of the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in

Childhood (ISAAC). Thorax 2009;64:476-83. CrossRef

7. Wong GW, Leung TF, Ko FW. Changing prevalence of

allergic diseases in the Asia-pacific region. Allergy Asthma

Immunol Res 2013;5:251-7. CrossRef

8. Wong GW, Leung TF, Ma Y, Liu EK, Yung E, Lai CK.

Symptoms of asthma and atopic disorders in preschool

children: prevalence and risk factors. Clin Exp Allergy

2007;37:174-9. CrossRef

9. Smit DV, Cameron PA, Rainer TH. Anaphylaxis

presentations to an emergency department in Hong Kong:

incidence and predictors of biphasic reactions. J Emerg

Med 2005;28:381-8. CrossRef

10. Leung TF, Yung E, Wong YS, Lam CW, Wong GW. Parent-reported

adverse food reactions in Hong Kong Chinese

preschoolers: epidemiology, clinical spectrum and risk

factors. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2009;20:339-46. CrossRef

11. Ho MH, Lee SL, Wong WH, Ip P, Lau YL. Prevalence of

self-reported food allergy in Hong Kong children and

teens—a population survey. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol

2012;30:275-84.

12. Lai CK, De Guia TS, Kim YY, et al. Asthma control in the

Asia-Pacific region: the Asthma Insights and Reality in

Asia-Pacific Study. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2003;111:263-8. CrossRef

13. Rabe KF, Adachi M, Lai CK, et al. Worldwide severity and

control of asthma in children and adults: the global asthma

insights and reality surveys. J Allergy Clin Immunol

2004;114:40-7. CrossRef

14. Zainudin BM, Lai CK, Soriano JB, Jia-Horng W, De Guia

TS; Asthma Insights and Reality in Asia-Pacific (AIRIAP)

Steering Committee. Asthma control in adults in Asia-Pacific. Respirology 2005;10:579-86. CrossRef

15. Wong GW, Kwon N, Hong JG, Hsu JY, Gunasekera KD.

Pediatric asthma control in Asia: phase 2 of the Asthma

Insights and Reality in Asia-Pacific (AIRIAP 2) survey.

Allergy 2013;68:524-30. CrossRef

16. Chan-Yeung M, Lai CK, Chan KS, et al. The burden of

lung disease in Hong Kong: a report from the Hong Kong

Thoracic Society. Respirology 2008;13 Suppl 4:S133-65. CrossRef

17. Vital statistics on mortality. Department of Health website: http://www.healthyhk.gov.hk/phisweb/en/health_info/vit_stat/mortality/. Accessed Sep 2014.

18. Wong GW, Mahesh PA, Ogorodova L, et al. The

EuroPrevall-INCO surveys on the prevalence of food

allergies in children from China, India and Russia: the

study methodology. Allergy 2010;65:385-90. CrossRef

19. Leung R, Ho A, Chan J, Choy D, Lai CK. Prevalence of latex

allergy in hospital staff in Hong Kong. Clin Exp Allergy

1997;27:167-74. CrossRef

20. Warner JO, Kaliner MA, Crisci CD, et al. Allergy practice

worldwide: a report by the World Allergy Organization

Specialty and Training Council. Int Arch Allergy Immunol

2006;139:166-74. CrossRef

21. Wüthrich B. Unproven techniques in allergy diagnosis. J

Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 2005;15:86-90.

22. Ho MH, Wong LM, Ling SC, et al. Identifying the service gaps in the management of severe systemic allergic reaction/anaphylaxis by Paediatrics Departments of the Hospital Authority. HK J Paediatr (new series) 2010;15:186-97.

23. House of Lords Science and Technology Committee.

Allergy: HL 166-I, 6th Report of Session 2006-07—Volume

1. The Stationery Office Ltd; 2007.

24. Pawankar R, Canonica GW, Holgate ST, Lockey RF. WAO

White book on allergy 2011-2012: Executive summary.

WAO White book on allergy. Milwaukee, Wisconsin:

World Allergy Organization; 2011.

Find HKMJ in MEDLINE: